| In foreign exchange, there must always be a winner and a loser. A series of zero-sum games, one currency or another gains in any pair. And the market is now telling us some startling things. One is that the dollar is in an upswing, which on the face of it implies that times are bad for the global economy; the dollar generally prospers when people are risk-averse. Another is, as several people now put it, the pound is beginning to behave as though it were an emerging market currency. Not just decoupling from mainland Europe, post-Brexit Britain appears to be separating from the entire developed world. In the case of the dollar, it is benefiting both from concerns that the latest wave of Covid-19 and China's problems will dent global growth, and also from the perception that the Federal Reserve will need to grow more hawkish from here. As George Saravelos, foreign exchange strategist at Deutsche Bank AG, put it when slightly upgrading his forecasts for the end of the year, "persistently stagflationary dynamics — lower growth but a hawkish Fed — leave little room for a dollar downtrend." The corollary is that if Covid-19 clears, China muddles through and reflation resumes, this latest dose of dollar strength could look like a head fake, but that is for the future. Kit Juckes of Societe Generale SA similarly suggests that the dollar is strong for reasons that are counterintuitive and not necessarily good news for the world economy: At almost USD 730bn in the last year, the US current account deficit may seem dangerously large, but China, Korea, Taiwan and Japan have a combined surplus that is the same size as the US deficit and the Eurozone runs a USD 380bn surplus. As long as Japan and the Eurozone are caught in a trap of QE and zero/negative rates, the notion that the US deficit is bad for the currency is outdated when the world's excess savings are gravitating towards US asset markets

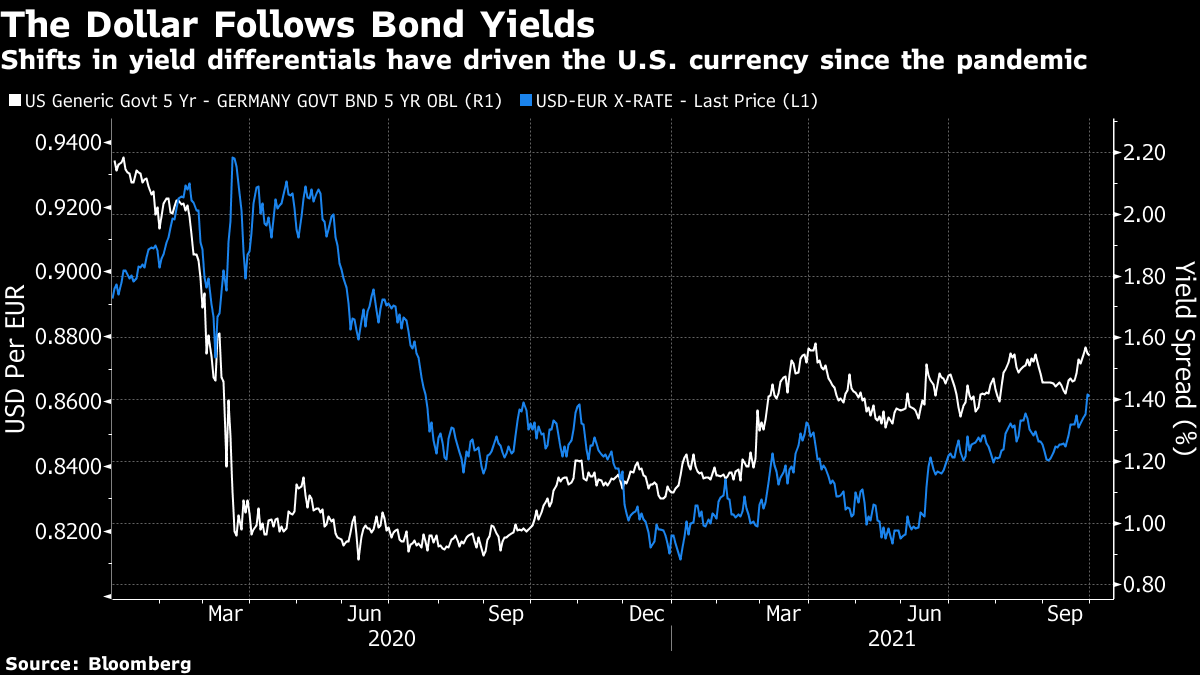

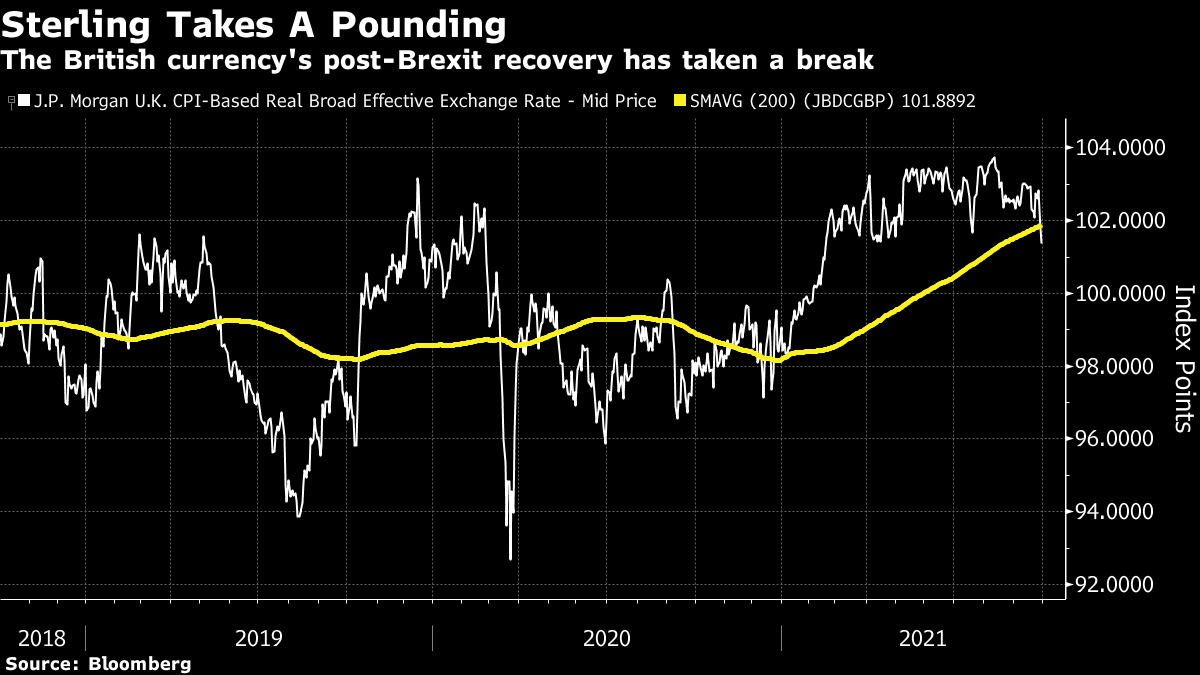

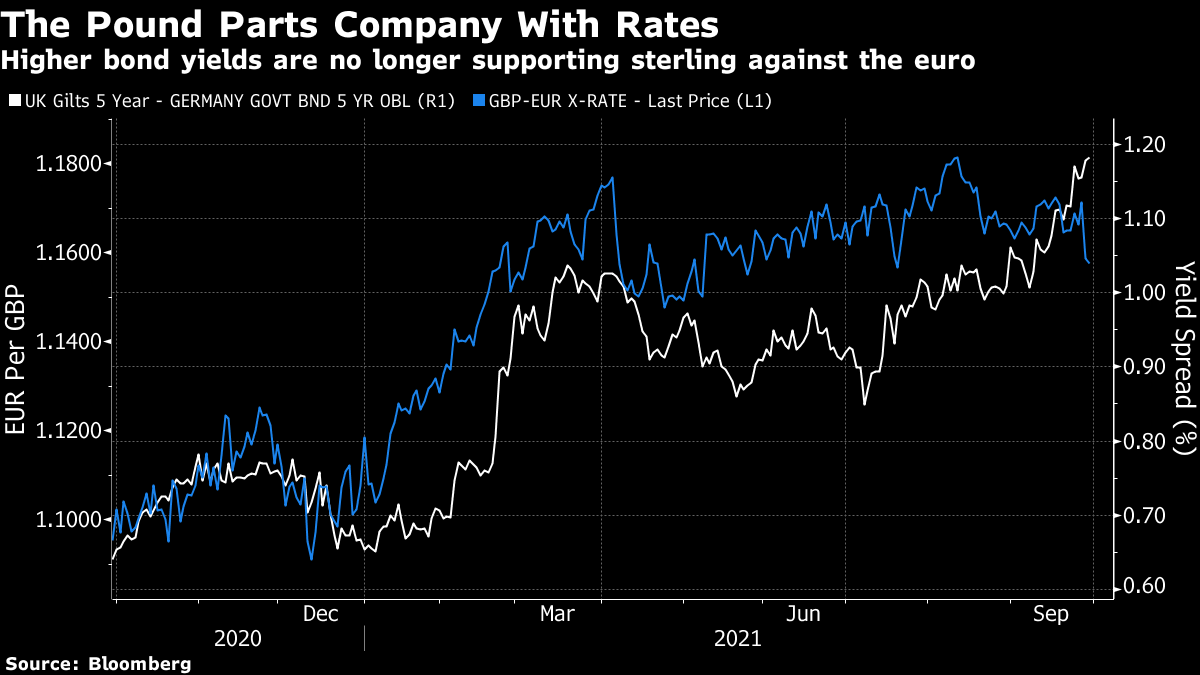

And for the time being, the yields on offer in the U.S. are attracting funds to the dollar. Treasury yields are rising compared to equivalent bund yields, just as they tanked with the onset of the pandemic last year — in both cases, shifts in yield differentials have eventually moved the dollar with them:  As for sterling, something more profound is afoot. It had staged a recovery in the last year, as the indignities of Brexit moved further into the past. But it has tanked in the last few days. This is JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s real effective rate (taking into account different inflation rates) for the pound, compared to a wide range of currencies. An upward trend has suddenly ended:  Perhaps more concerning, this is happening even though the Bank of England appears to be readying to raise rates, and yield differentials have moved in sterling's favor, compared with continental Europe. This helped the dollar; it no longer helps the pound:  Britain's fuel crisis isn't a great advertisement for the country, and its clumsy attempts to sort out a new trading relationship with Europe post-Brexit aren't looking good. These are the kind of idiosyncratic risks that nullify any good a rate hike might have done for the currency. It's exactly the kind of problem that finance ministers of emerging economies know all too much about. Marc Chandler, of Bannockburn Global Forex, puts it this way in his marctomarket blog: The market seems to be worried about a policy mistake. Monetary and fiscal policy is set to tighten, and the higher energy prices, in this context, are like another consumption tax. Part of the energy shortage in the UK is also idiosyncratic and related to structural conditions of the labor market on this side of Brexit. Meanwhile, it [is] antagonizing Europe by granting only 12 of 47 applications for fishing licenses, and the debate over the Northern Ireland protocols appears to be intensifying.

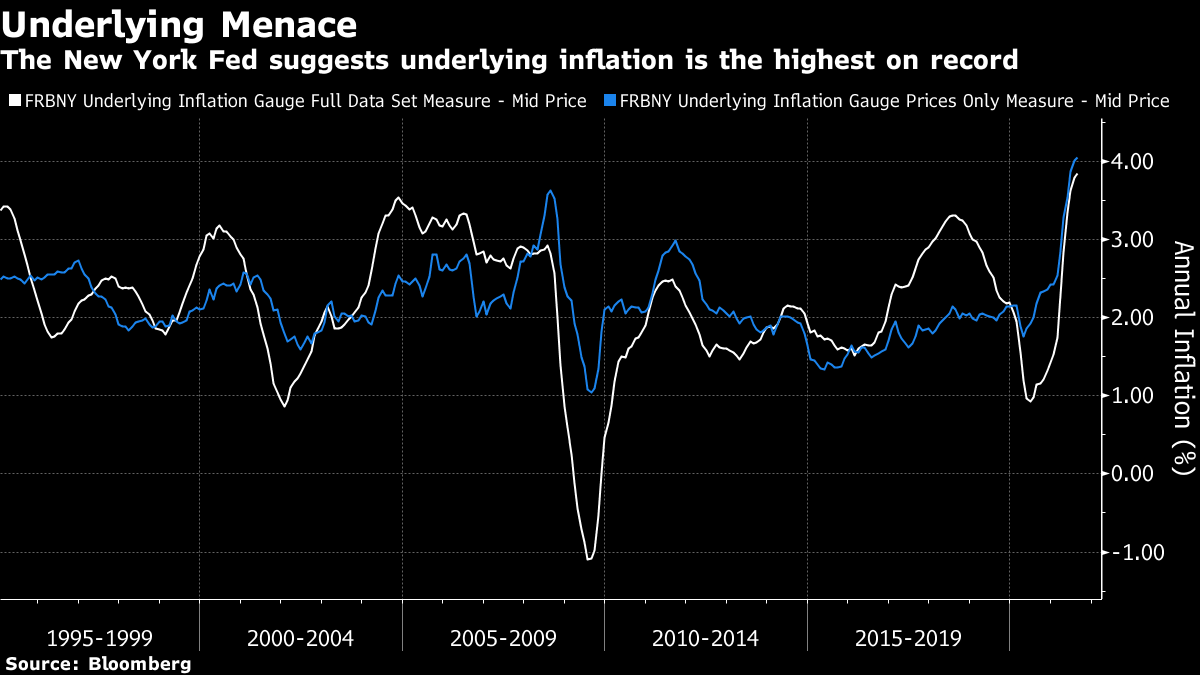

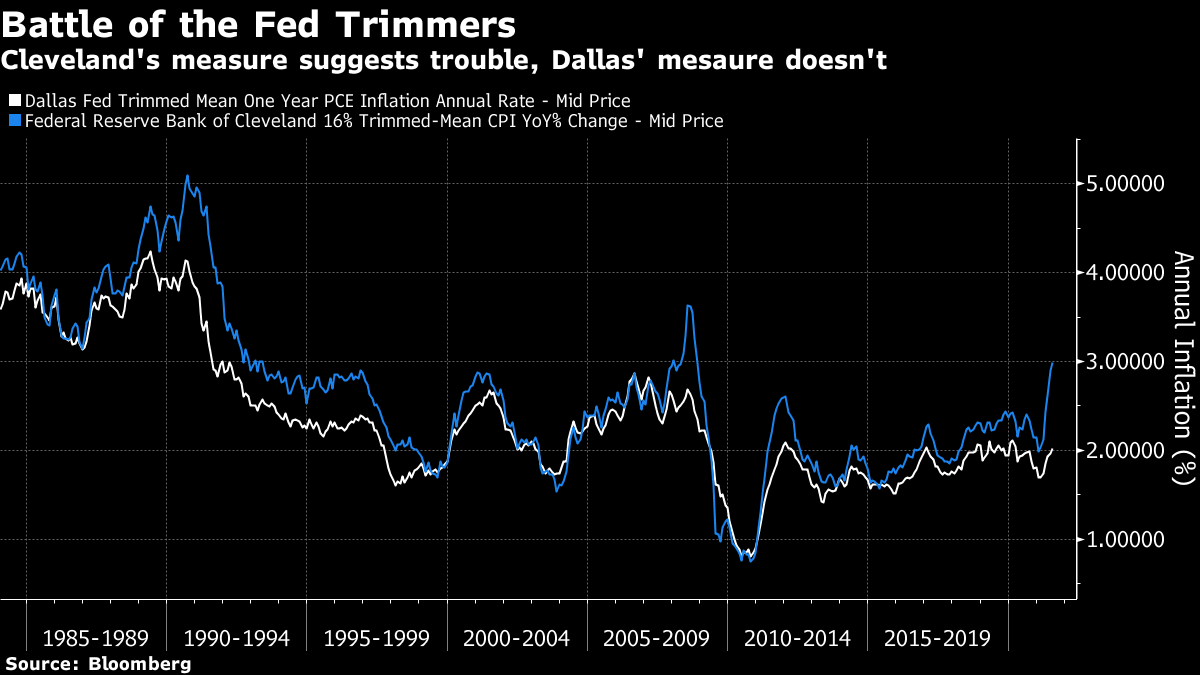

As a rule, the word "idiosyncratic" tends to be reserved for emerging markets which are in so much bother that rate hikes won't help them. If the foreign exchange market thinks Britain has idiosyncratic problems, that's not good. As a general rule, it's a bad sign if you take any interest in the plumbing in your house, or the strength of your internet router. These things could only possibly interest you if something were going wrong. The same can be said for TED spreads, T-bill yields and the rates available on commercial paper, as the global financial crisis showed. By the same token, it's bad news that we all now know so much more about inflation statistics. Over the last few months, many of us have learned about the different statistical techniques for deriving a "core" or "trend" or "underlying" rate of inflation. A few months ago, such measures generally helped the argument that the big rise in the headline index was a transitory phenomenon sparked by pandemic effects. Prices of car rentals or used cars, for instance, would soon return to normal after nearly doubling in a year. This indeed is happening. Now, however, it is the sophisticated measures of underlying inflation that are suggesting reason for alarm. Since 1996, the New York Fed has calculated an underlying rate of inflation, on two separate bases. One includes all the price data kept by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for calculating the consumer price index, or CPI. The other includes more macroeconomic measures that tend to be linked to inflation. The idea is to use statistical techniques to identify an underlying rate. A full explanation by the Fed can be found here. Earlier this year, both measures suggested there was little or nothing to worry about. Now, both are their highest since the New York Fed embarked on the exercise in 1995:  The headline numbers have reduced slightly, which is good news. But as the Fed has put in the time, money and effort to produce these figures, it's fair to assume they would influence what the central bank does next. And they suggest policy makers will see an accelerating inflation picture (albeit not an extreme one), and take evasive action. The plot thickens if we move on to the Cleveland and Dallas Feds, both of which are in the business of producing "trimmed means" — measures where the biggest outliers in either direction are excluded, and inflation is calculated by taking the average of the rest. Cleveland does this for the CPI, which uses a fixed measure of goods and services, while Dallas trims the means of the personal consumption expenditure, or PCE, deflator, which uses a flexible basket, so that goods will have a smaller weighting when consumers buy less of them. The argument for this is that it more accurately reflects exactly what people are buying, while the case against is that it can understate inflationary effects by excluding goods where price rises deter purchases that would other otherwise have been made. The Dallas Fed Trimmed PCE still hasn't been updated for last month. Here is how the two measures have moved since 1984:  As might be expected, the two tend to track each other, and the CPI tends to be higher. The Cleveland CPI measure has just leapt in a worrying way to show the highest inflation pressure in a decade. The Dallas PCE remains comfortably within its post-crisis range, and far below pre-crisis levels. Judging by past experience, the Dallas indicator may be due for a sharp rise. But as things stand, they are sending different signals. Finally, there are differences of opinion at the Fed over the weight to put on inflation expectations. In theory, anticipated price rises make people more likely to buy things now (to avoid future increases) and thus become self-fulfilling. For this reason, there is tight monitoring of expectations, both as measured in consumer surveys and by the mathematical inflation predictions generated in the bond market. A new paper by Jeremy Rudd a long-serving economist at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, covered in a column by Bloomberg Opinion's Brian Chappatta here, lambasts the entire notion that inflationary expectations drive inflation, and suggests that it may be wiser to take action earlier in the cycle. The title says it all: Why Do We Think That Inflation Expectations Matter for Inflation? (And Should We?) I don't know enough about the court politics of the Fed to understand exactly why and how this paper came to be published, but it plainly reveals dissension or even infighting within the central bank. It also shows an impressive degree of intellectual freedom and transparency that the institution's employees are allowed to air differences so publicly. Rather than a typical piece of economic research, with lots of data, some statistical regressions, and a model with some Greek letters, the paper is more of a polemical review of arguments that have long been in the public domain. Several passages imply some strange palace intrigues. For example, the initial argument is followed by this passage: A reasonable reader's reaction to the preceding discussion might be: "So what? No model is going to describe reality all that well, and a convincing theory of aggregate supply—or of inflation dynamics generally—has eluded students of macroeconomics since the field's inception. So your criticisms really just amount to ill-tempered pettifogging."

I know at least one person whose response to the paper was almost exactly this. Did someone at the Fed also say this? The paper also contains one of the most remarkable footnotes ever to appear in a piece of central bank research: I leave aside the deeper concern that the primary role of mainstream economics in our society is to provide an apologetics for a criminally oppressive, unsustainable, and unjust social order.

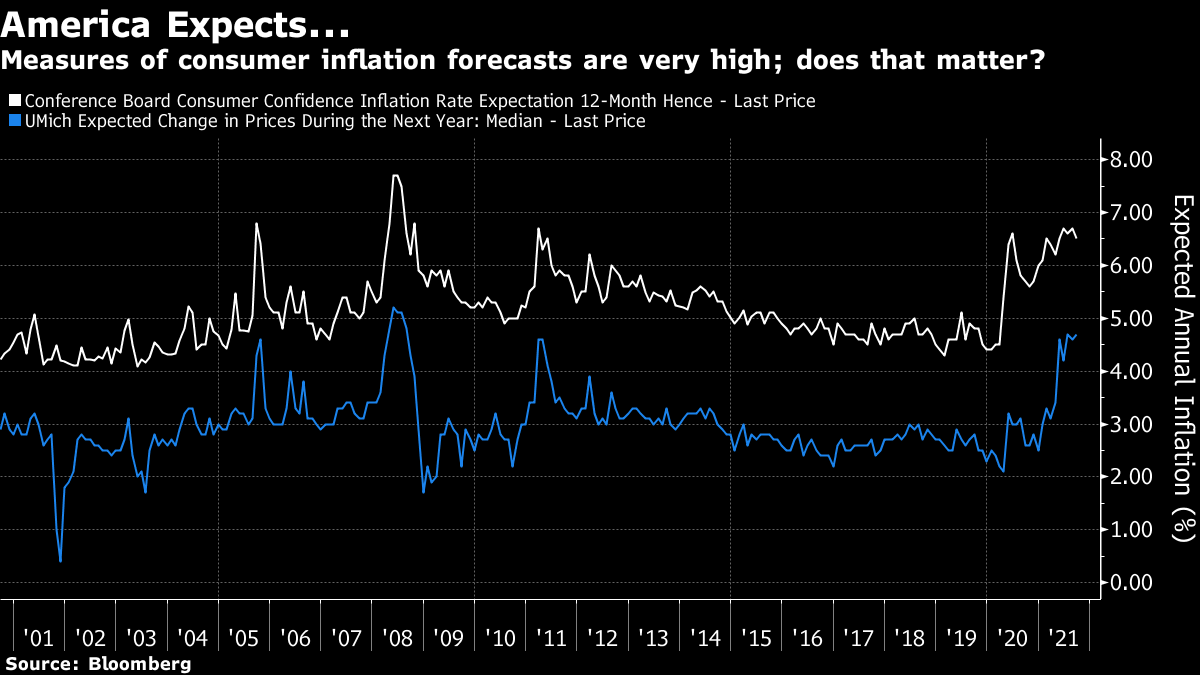

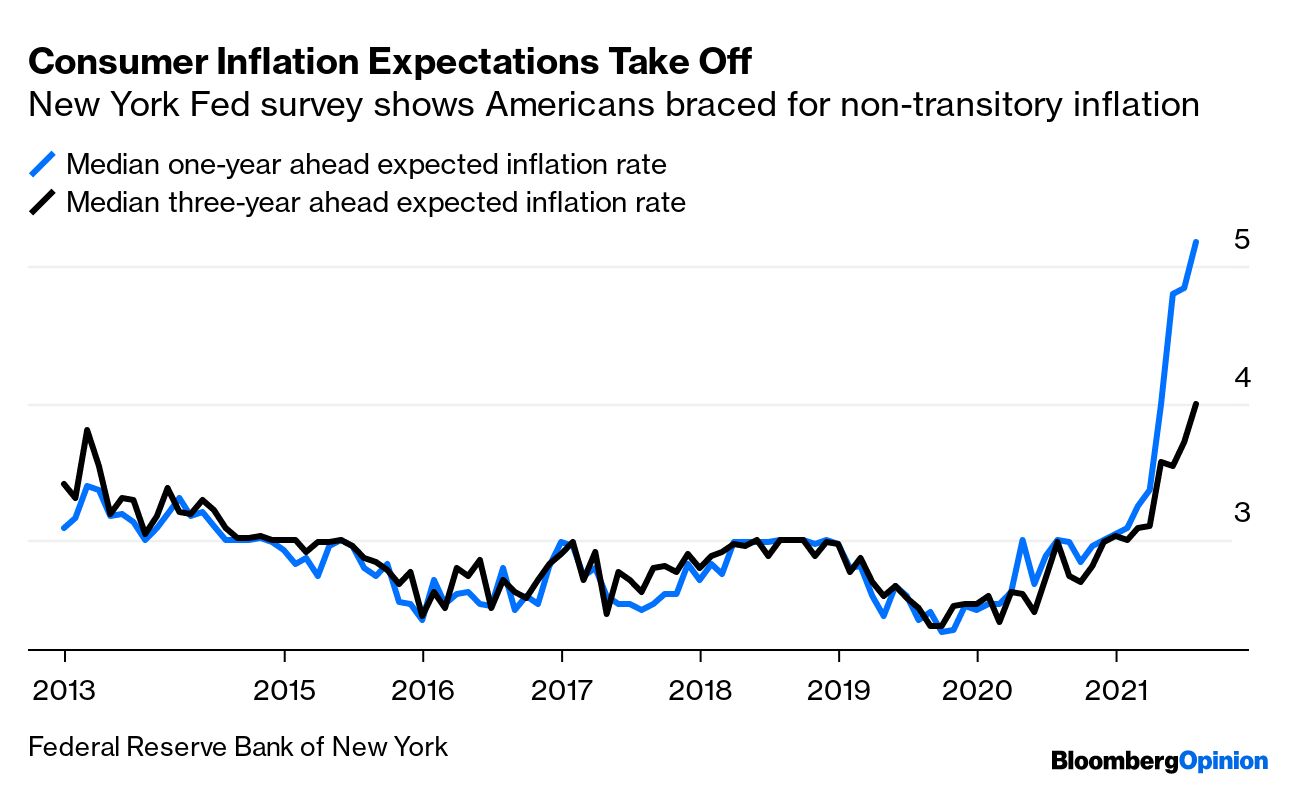

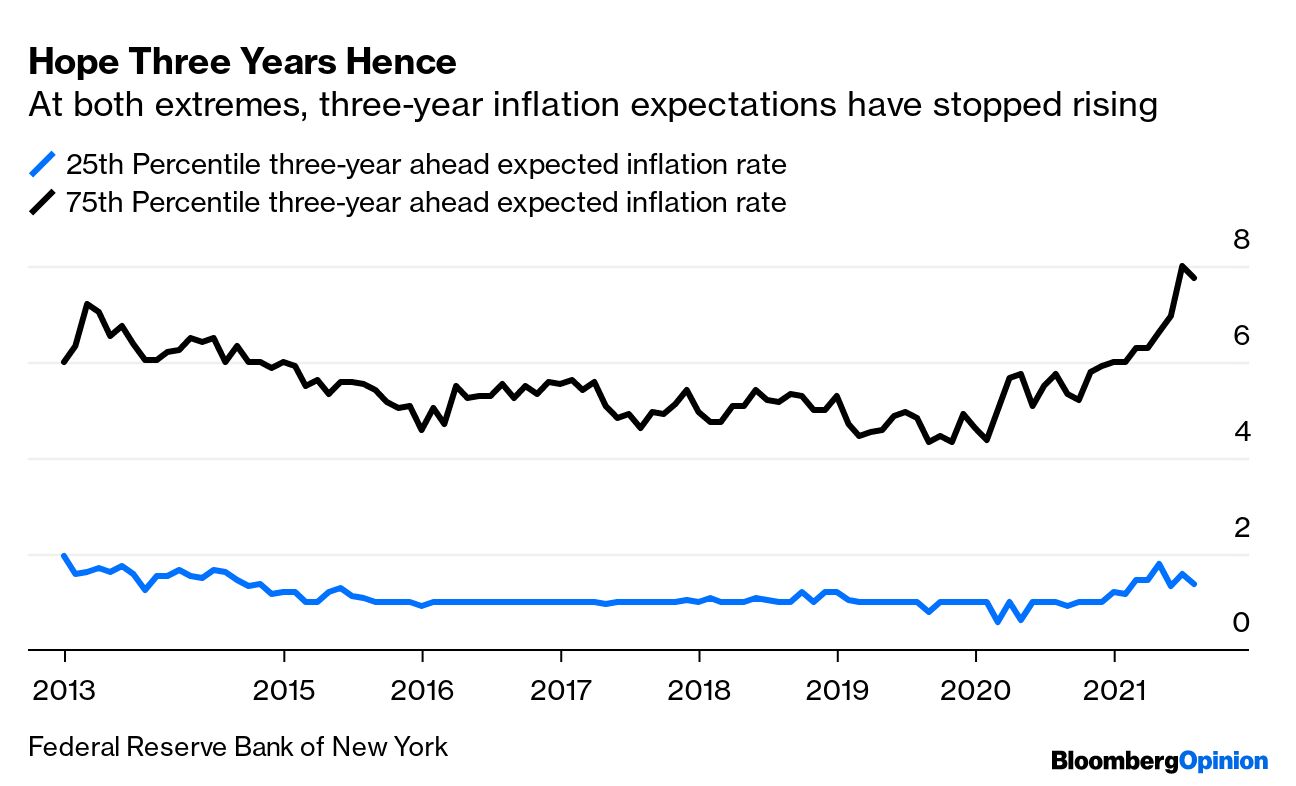

A paper under the Fed's imprimatur that tackled that concern head-on would certainly have made for fascinating reading. Again, it's discordant language in a central bank paper. The whole thing is written in more of a journalistic style than the dry academic language typical of the Fed's economic papers, and it is very combative. It's also packed with literary references. The final paragraph, headed with a quote from The Second Coming by W.B. Yeats, begins with an invitation to "consider the following Gedankenversuch." On the face of it, the paper is a clarion call arguing that the Fed's approach is wrong. Rudd contends that the Fed should be watching measures such as the extremely high quit rate, which suggests that the labor market is tight. The entire paper reads as a criticism for the great amount of work that the Fed currently puts into measuring inflation expectations. Surveys of consumers by other organizations suggest that expectations rose sharply earlier this year, and have now stopped. That is the picture in the latest reports from the Conference Board and the University of Michigan:  Both surveys reveal that consumers persistently overestimate future inflation. What is more interesting is the New York Fed's own work surveying consumers, which has been conducted since 2013. If inflation expectations can in and of themselves cause inflation, rather than merely being side-effects of other factors, as Rudd argues, then the survey is alarming. The following chart shows the median expected inflation rates one and three years ahead. Both are their highest since the surveys began eight years ago:  This looks very concerning. But expectations are widely dispersed — the 25th and 75th percentiles show that a large share of consumers are still assuming that inflation will stay totally under control, and even those most worried about long-term inflation are slightly less concerned than they were a month ago:  Where does all of this leave us? By virtually any sensible measure that the Fed has been following, it looks as though the rise in prices should be causing concern. And plenty of esoteric arguments have been revived. If you're arguing about the plumbing, it's a good sign that your house is flooding. The fact that the world's most powerful central bank is having public disagreements over inflation, how to measure it, and how to gauge expectations is not encouraging.  | This is Banned Books Week. Being banned is generally a great seal of approval for any book, and banned books should be celebrated. The American Libraries Association produced a Top 100 list of the books that saw the greatest efforts to have them banned and withdrawn from schools and libraries in the U.S. during the last decade. They include the likes of To Kill A Mockingbird, 1984, Brave New World, and Of Mice and Men. Reading a book, as opposed to staring at a screen, is good for the soul in any case, as my colleague Stephen L. Carter points out. In these polarized times, all of us might benefit from reading a book whose point of view we think we'll find offensive. So why not make yourself happier, and your mind broader, and strike a blow for freedom and against censorship, by reading one of the books on the list? Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment