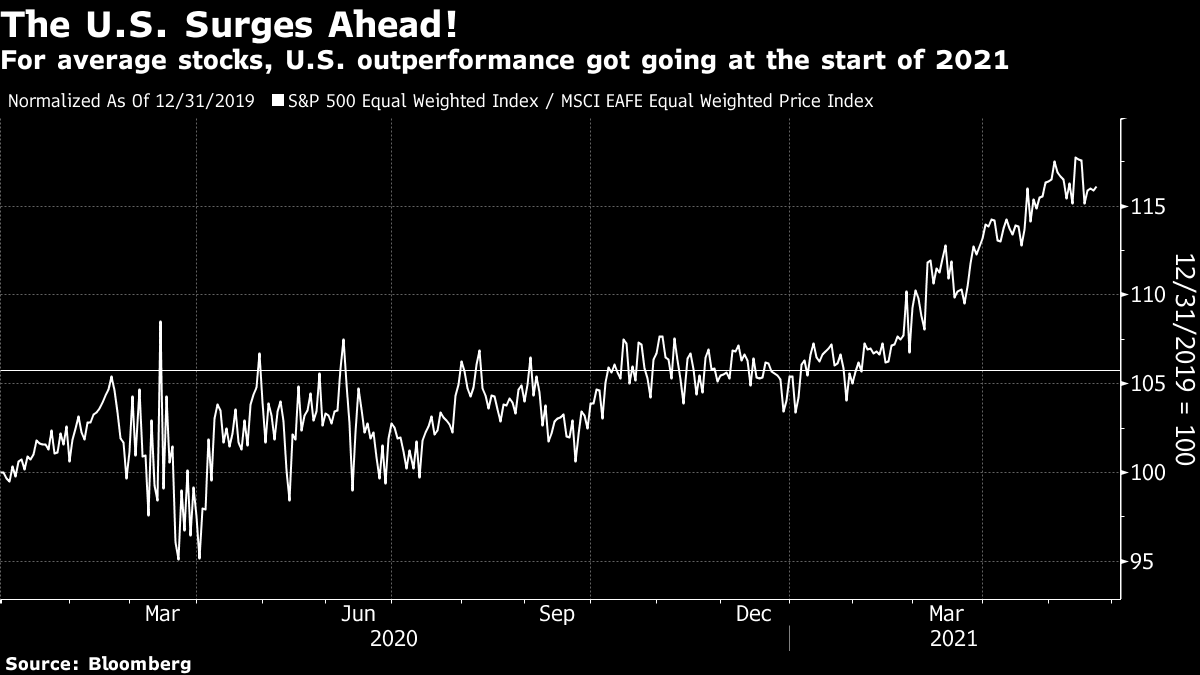

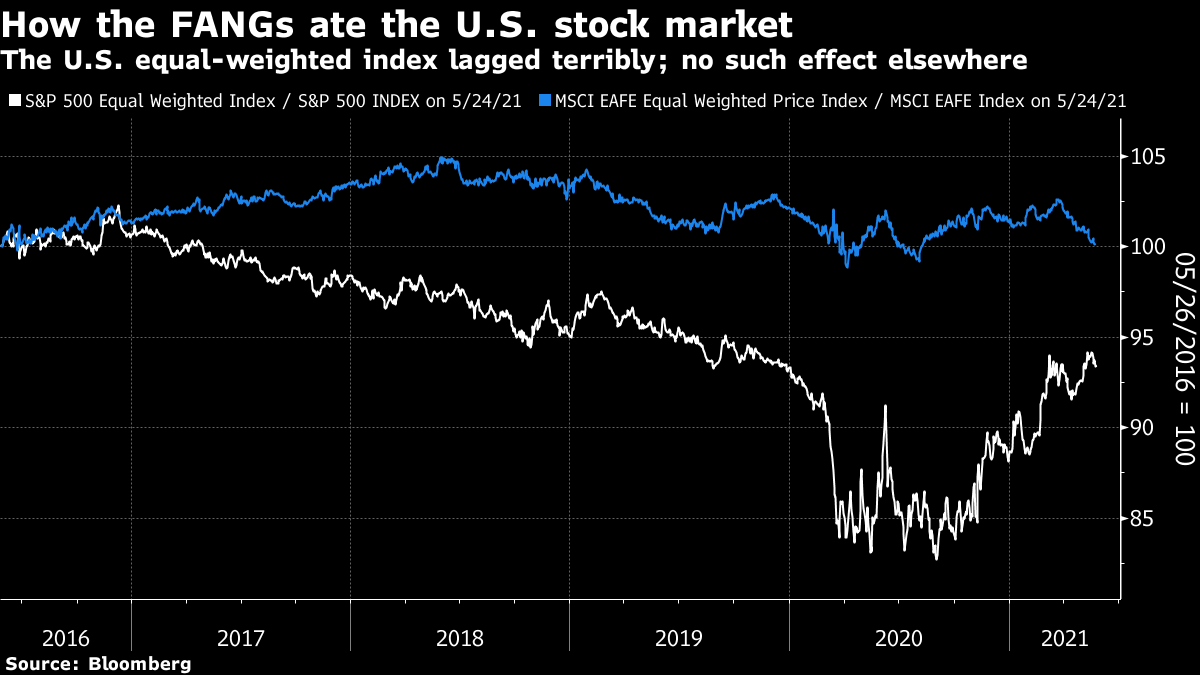

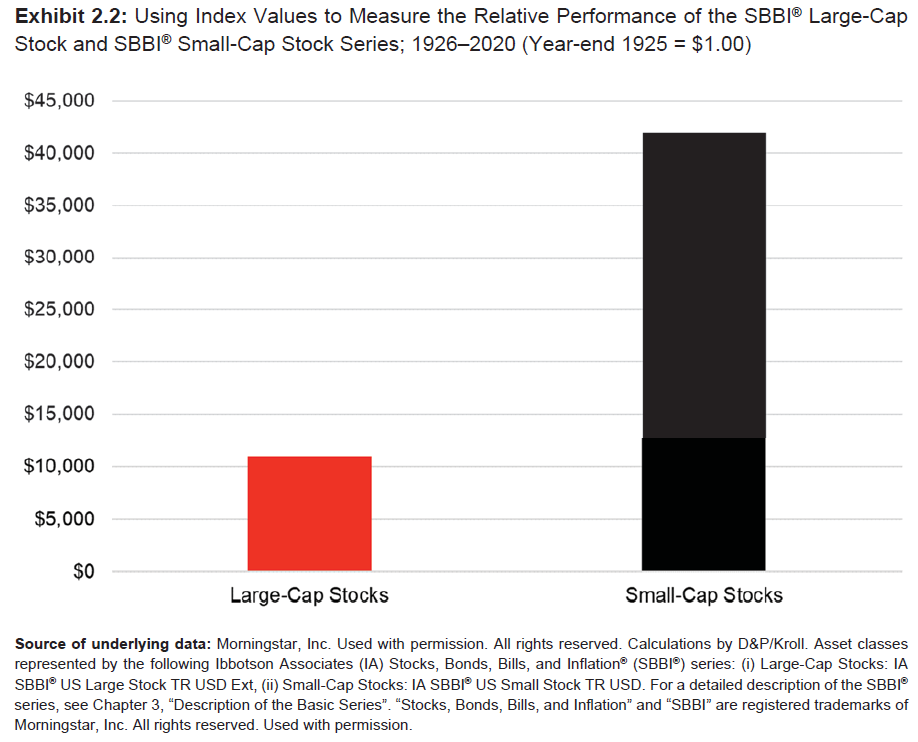

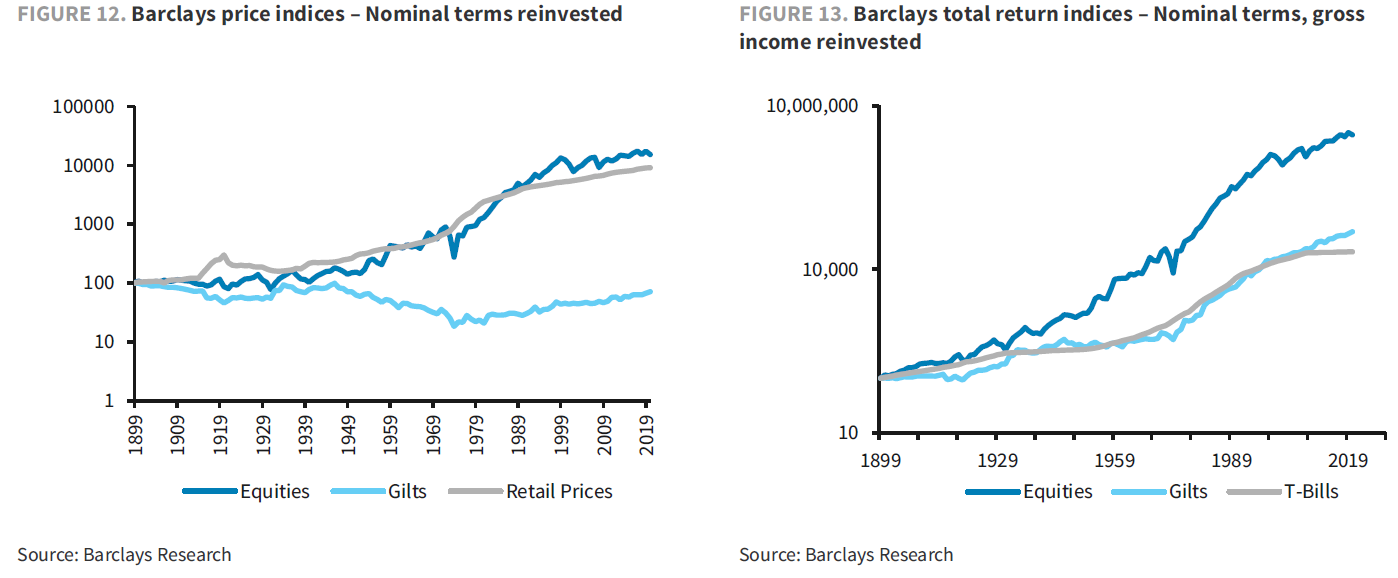

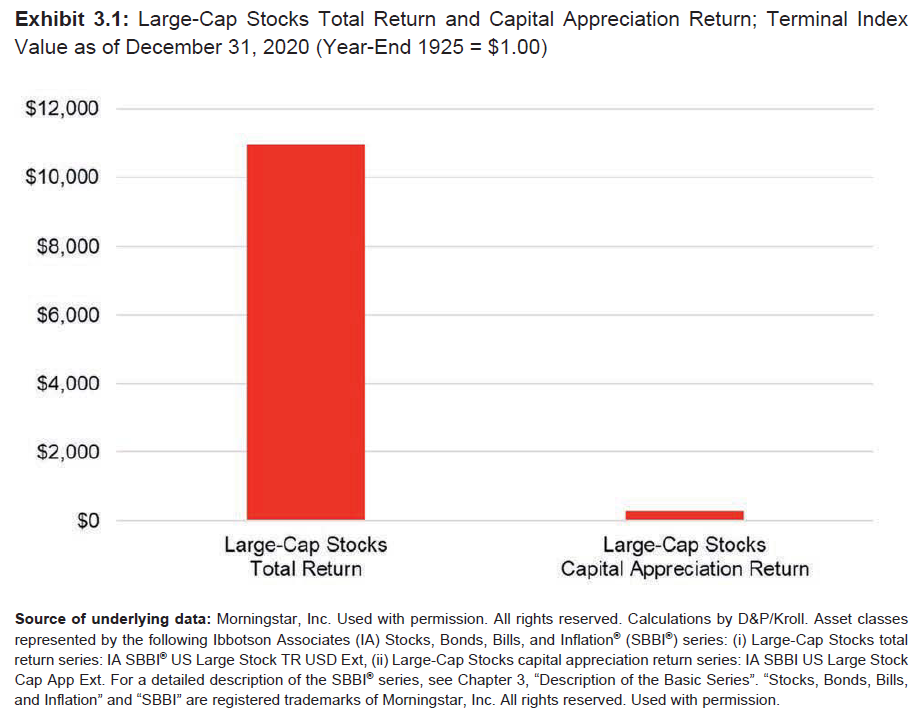

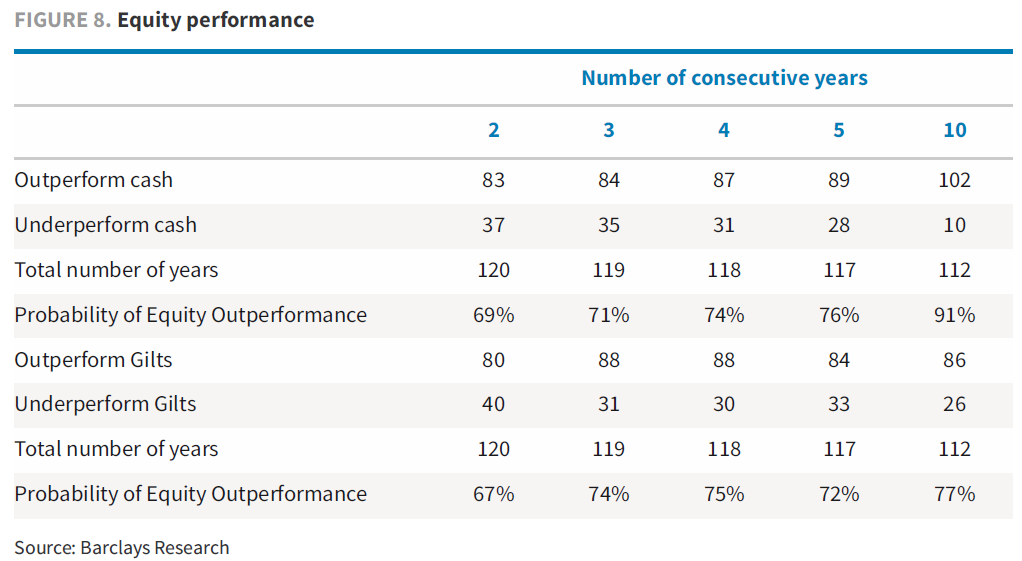

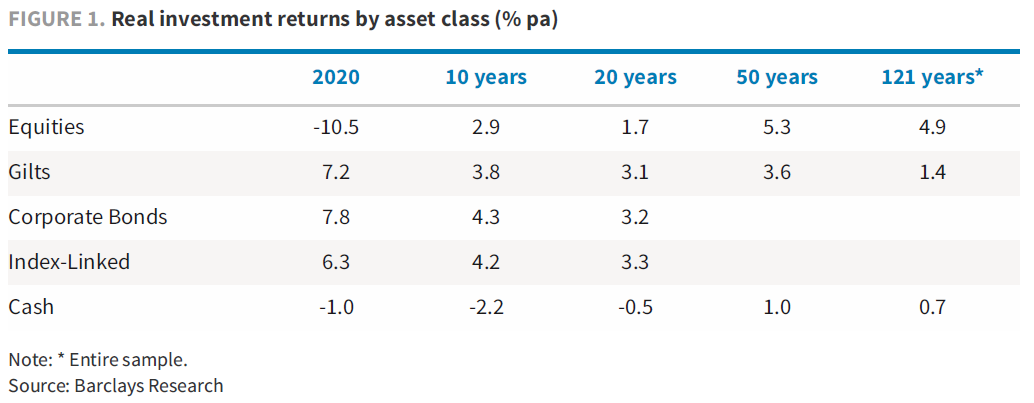

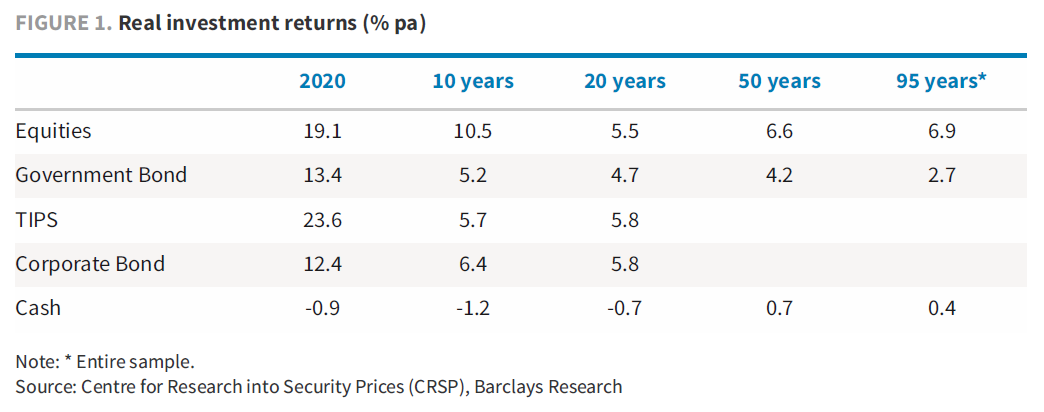

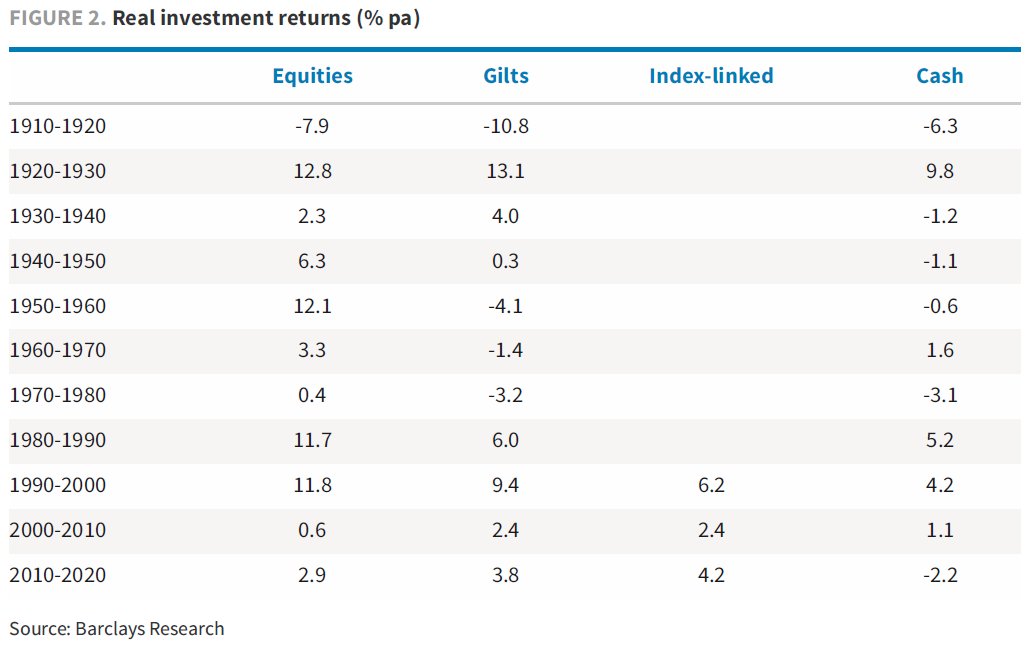

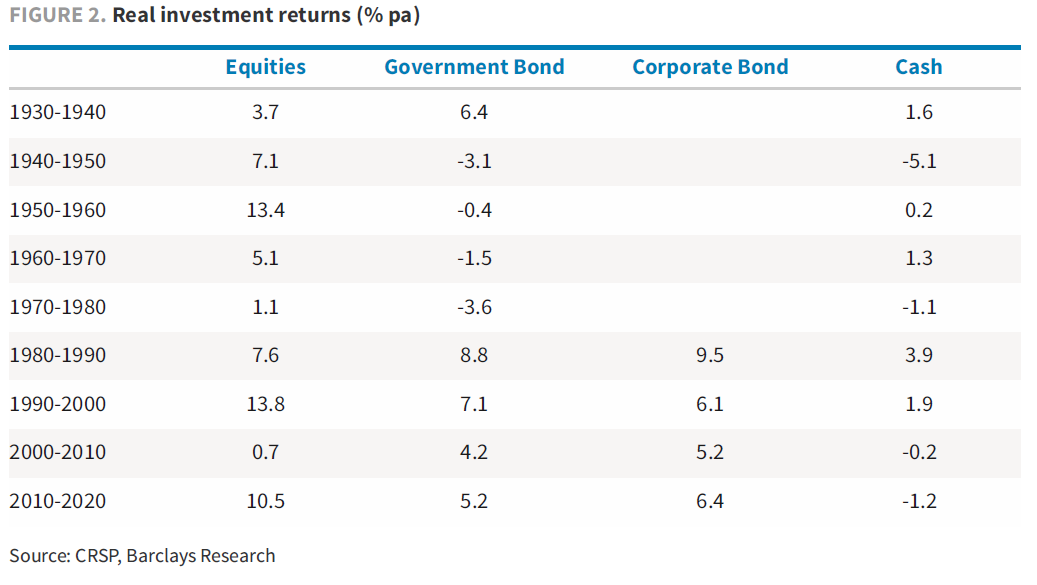

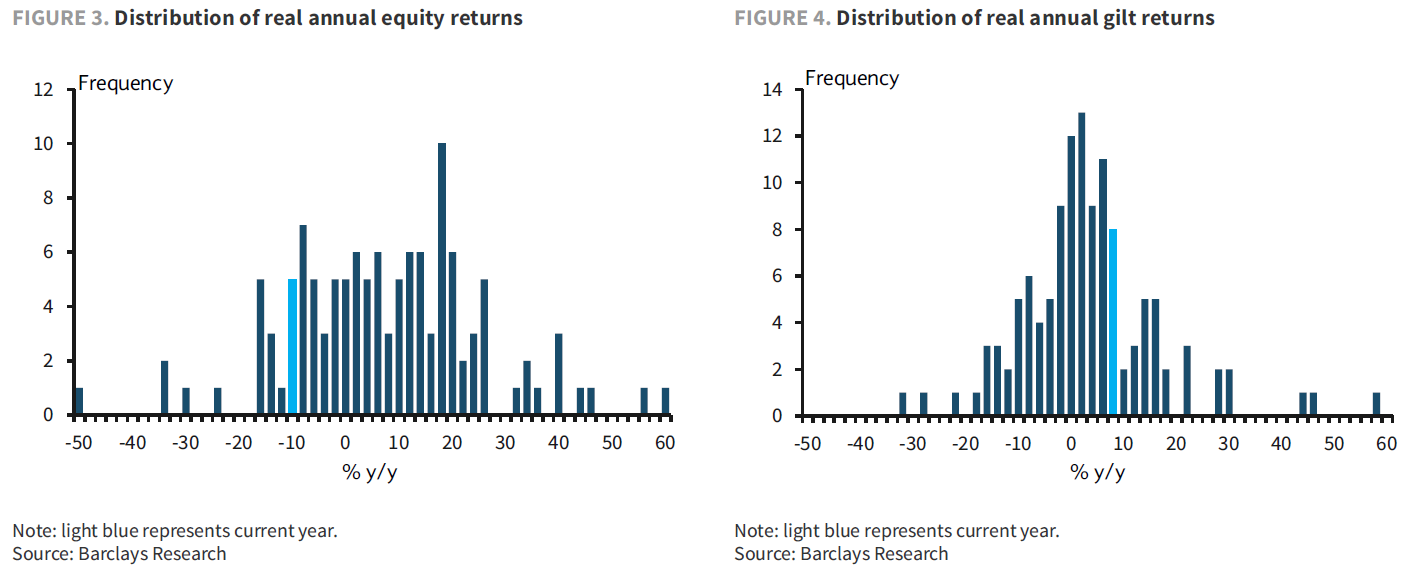

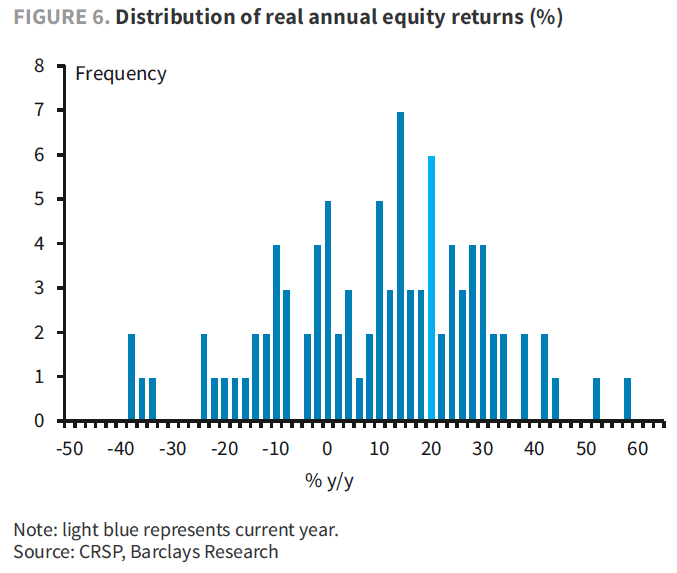

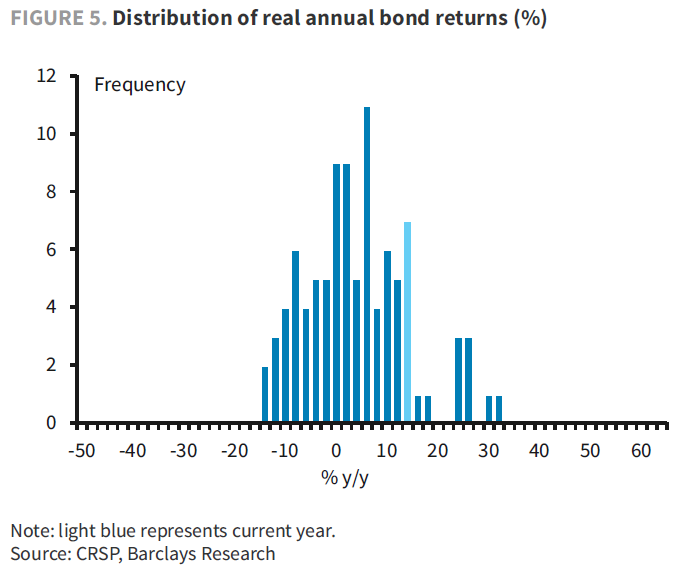

America De-FANGed Is Even StrongerMarket cap-weighted indexes have been blamed for many things. There are good arguments against using them, not least because of their tendency to direct money toward stocks that tend already to be overvalued. But over the last year they may also be giving a false impression of the strength of corporate sectors in different parts of the world. Here is how the S&P 500, the most popular index of large U.S. stocks, has fared compared to the MSCI EAFE index covering Europe, Australasia and the Far East, the most popular gauge of developed markets outside the U.S., since the beginning of last year.  After fantastic outperformance during the pandemic, the U.S. has allowed the rest of the world to catch up since last September. This seems strange on a number of levels. As of September, the U.S. had just suffered its second wave of Covid-19 in the Sun Belt states, while Europe had enjoyed a relatively Covid-free summer, and appeared to have managed the pandemic far better. That narrative has turned around since then. The U.S. has seen the political "Blue Wave," which wasn't in the price in September, and this has led to far more aggressive fiscal stimulus than had been expected. In the short term this should have directly helped the U.S. stock market (although there is room for much more debate over the longer term). Now let's look at the same chart using equal-weighted indexes. Each stock counts for the same proportion of each index, regardless of size. Apple Inc., Amazon.com Inc, Microsoft Corp., Alphabet Inc. and Facebook Inc. account for exactly 1% of this version of the S&P 500, even though they have been far more than 20% of the market cap-weighted index over this period. With the FANG stocks thus cut down to size, this is how the average U.S. stock has fared compared to the average EAFE stock:  This accords far more with what we might have expected given the course of the pandemic. U.S. stocks did outperform during 2020, which was stable for much of the latter half of the year, but it was far less marked than in the cap-weighted version. We can probably thank the Federal Reserve for that. The real trend of dramatic and persistent outperformance starts almost exactly when Joe Biden takes the White House accompanied by narrow majorities in Congress. For the average stock, the jolt administered by the Democrats' fiscal stimulus, combined with a more successful vaccine rollout, was enough to ensure that the U.S. did far better. The really dramatic and unusual effect of last year in the stock market was the massive impact of the FANG stocks. This is how the equal-weighted index fared compared to the cap-weighted, starting at the beginning of last year, for both the U.S. and EAFE:  Just to show how anomalous this year has been, here is the longer-term performance of the average stock compared to the index in the U.S., since the equal-weighted index began in 1988:  Generally, and logically, the average stock will do better. The equal-weighted index gives extra weight to companies that haven't grown so much yet, so this makes sense. The two previous big exceptions were the other two major market busts since 1988 — the dot-com bubble, when a group of tech stocks became absurdly overvalued and the equal-weighted index looked worst at the top of the market; and the global financial crisis of 2008, when only a few big and relatively boring defensive stocks like Walmart Inc. held their value, and the equal-weighted index looked worst at the market bottom. In both cases, the correction afterwards was swift and emphatic, so history suggests we can expect the U.S. equal-weighted index to keep up its relative recovery. Judging by flows into exchange-traded funds, it again seems fair to expect quite a rebound. Invesco's ETF for the equal-weighted index, with the ticker symbol RSP, has seen $6.675 billion in new inflows for the year to date, which is equivalent to 37% of its assets under management at the outset, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The four ETFs that track the S&P 500 have attracted $22.4 billion between them, or 3% of their original assets under management. As RSP remains only 3% the size of the four market-cap weighted S&P 500 ETFs , there is plenty of scope for this to continue. As for the relative merits of the U.S. and the rest of the developed world, they are more complicated than they first appear. Taking away the distortion of the FANG effect, it does look as though European and Japanese stocks are priced on the assumption of further serious problems with the pandemic, a weaker fiscal response, and maybe more problematic politics. So there is probably a stronger case to go looking for interesting non-U.S. stocks now than might appear from the cap-weighted indexes. Long-run surveys provide the ultimate reality check. In the last few days we have seen the 66th edition of the Barclays Equity Gilt Survey, which originally covered the U.K. only but now covers the U.S., and the 2021 edition of the Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation survey, which started in 1976 and has data going back to 1926. These days it is published under the auspices of Morningstar Inc. and the CFA Institute. There is much to be mined from both. A quick gallop through some of the findings: Small-Caps for the long run In the long run, as the SBBI survey shows, U.S. small caps have utterly clobbered larger companies. That's more reason to consider what happened last year anomalous (and, after all, there were plenty of reasons why last year's weird conditions might create an atypical market).  Reinvesting dividends is good for you We all know that in the long run the extra returns of stocks come from dividend reinvestments, but it's still spectacular to see the numbers graphed out. In this chart, the figure on the left shows how stocks and gilts have done compared to inflation in nominal terms, while on the right we see the same figures with gross income reinvested, compared to U.S. Treasury bills:  Here is the SBBI calculation of the difference between returns on U.S. large-cap stocks with and without reinvested income, since 1926:  Stocks beat bonds, usually Everyone knows that stocks generally beat bonds, and they do, and over time that adds up. What is surprising is how long you might have to wait. If your time horizon is only as long as a decade, then stocks in the U.K. are likely to win but it's no sure thing, as the Barclays survey shows:  To decipher this chart, the chart asks in the first column how often equities outperform cash over two years, and the answer is 69% of the time, and so on. Over 10 years, equities have a 91% chance of beating cash, and only a 77% chance of beating gilts — in both cases, somewhat weaker than many of us would have guessed sight unseen. 2020 was different depending on which side of the Atlantic you were For British equity investors, last year was horrible, as you might expect. Stocks lost terribly to bonds:  For equities to shed 10.5% is unusual, particularly when gilts were gaining 7.2%. Things are so awful in the U.K. that gilts have also won over both the last one and two decades. The self-inflicted wound of Brexit definitely helped gilts, although I doubt even the most ardent Brexiteer could paint this as a patriotic triumph for the U.K. Treasury. Now, British stock investors are entitled to expect some mean reversion in their favor. Meanwhile, here is the same exercise for the U.S. The difference is astonishing:  The FANGs bailed out the massed 401(K) investors of the U.S. magnificently during the plague year. Equities massively outperformed government bonds (although not Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, which made a largely unremarked but enormous return of 23.6%). Over 50 years, the average return of U.S. equities is 1.3 percentage points higher than in the U.K., while Treasury bonds have an average annual return 0.6 percentage points higher than for gilts. Over 50 years of compounding, that is an immense difference, reflecting the greatly superior performance of the American economy over the last half century. Inflation s**ks As we're all worried about inflation at present, it's instructive to look at the experience of the 1970s, the decade when the Western world got its most serious dose in living memory. In Britain, equities offered protection against inflation, but only just, gaining 04% in real terms. Gilts lost. There was nowhere to hide, and no good returns to be made:  When Barclays performed the same exercise for the U.S., the results were similar. There was no refuge from inflation in the 1970s. Equities were better than bonds but still didn't provide the kind of returns that those trying to save for retirement would have needed. With far more people individually exposed to the risk of inadequate pensions now, rather than relying on corporate guarantees to make up any shortfalls, a return to inflation could be ugly:  The unexpected happens Last year was one of the extreme experiences in modern history. But neither the stock nor the bond markets really showed it. This is where 2020's returns fit into the historical pattern for the U.K., according to Barclays:  Neither equity nor bond returns show up as true outliers in the U.K. in this ultimate outlier year. And the same is true in the U.S. Both stocks and bonds had a solid well-above-average year:   You can take this as testament to the financial system's ability to assimilate the most extreme momentary shocks, or as evidence of the extreme distorting effect of money-printing by the Fed, according to taste. My own best guess is that the FANG effect flattered equity returns, while the Fed flattered bond returns last year; it might be best to brace for some mean reversion. Survival TipsAs the arts, and even sports, prepare to reopen in full force, there are still ways to enjoy high culture from the comfort of your own home. New York's Metropolitan Opera has had a tough lockdown, and doesn't reopen for next season until September — but it is still offering a free stream of a different opera every night. Each is available for 24 hours. This week and next are devoted to "hidden gems" including a number I know nothing about. However, I do know a little about tonight's opera, Prince Igor by Borodin, which includes the glorious Polovtsian Dances. They're quite a trip and worth watching.

Closer to my childhood home, the Glyndebourne Festival, nestled in the Sussex Downs, looks as though it will go ahead with restricted audiences this summer. This week it is showing Janacek's Kata Kabanova, while later on this summer they will get to Mozart's Cosi Fan Tutti (including Soave Sia Il Vento, possibly the most sublime trio ever written), and Wagner's mighty Tristan und Isolde. Glyndebourne is also being so good as to offer streaming. This week and next you can see another Janacek opera, The Cunning Little Vixen, and the link will take you to it on YouTube.

Finally, I should mention the English National Opera, dedicated to putting on operas in English at affordable prices. Their very worthy contribution for the pandemic-scarred era is ENO Breathe, an online course that helps Covid sufferers who still have difficulty breathing by applying some of the lessons of singing. The details are here, and it's a great idea. Institutions like opera houses are generally seen as playgrounds of the rich, often with some justice; it's great that they're not only giving something during a period when they are starved of income, but that it's actually practical. There is nothing like trying to sing to help get your posture and breathing into order. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment