| To get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here. Britain Takes Back ControlBrexit was and is a terrible idea. I voted against it and have no regrets. In economic terms, the U.K. decisively shot itself in the foot by cutting itself off from the world's largest free-trade bloc, which sits right on its border. Economically, leaving the European Union is never going to look like a good choice. Meanwhile, Britain's policy toward dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic has been a yearlong disaster, characterized by unpredictable U-turns, with excessive clampdowns succeeded by premature permissiveness, and ended with the dreadful luck of falling victim to the world's first major mutation of the virus. Prime Minister Boris Johnson's role in persuading his countrymen to go along with the first of these national catastrophes was disgraceful; his leadership during the second has been hopelessly erratic. Having got all of that off my chest, I now intend to lay out what looks like a strong case for bullishness about the U.K., which also illuminates the case for positivity about a range of other assets around the world that should benefit from reflation and recovery from the pandemic. Three key points are necessary. The first is that in markets, what matters is the news that is in the price when you buy. If the market has already discounted the bad news, you might still have a great investment on your hands. Second, while the U.K. shot itself in the foot with Brexit, it didn't shoot itself in the head. The country can still trade with the EU, at somewhat less preferential terms, and it may yet gain some small advantage from trade deals with others. While plainly negative for the economy, leaving won't be terminal. And third, the pandemic has thrown up a series of challenges to governance, and strong performance in one stage of the battle says nothing about performance in the next. Having mishandled lockdowns terribly, Britain now appears to lead the world in vaccinations. It's always possible that the virus will bring some fresh horror, but a good record in vaccinating the population will make a huge difference. Now, about that bull case.

Sterling

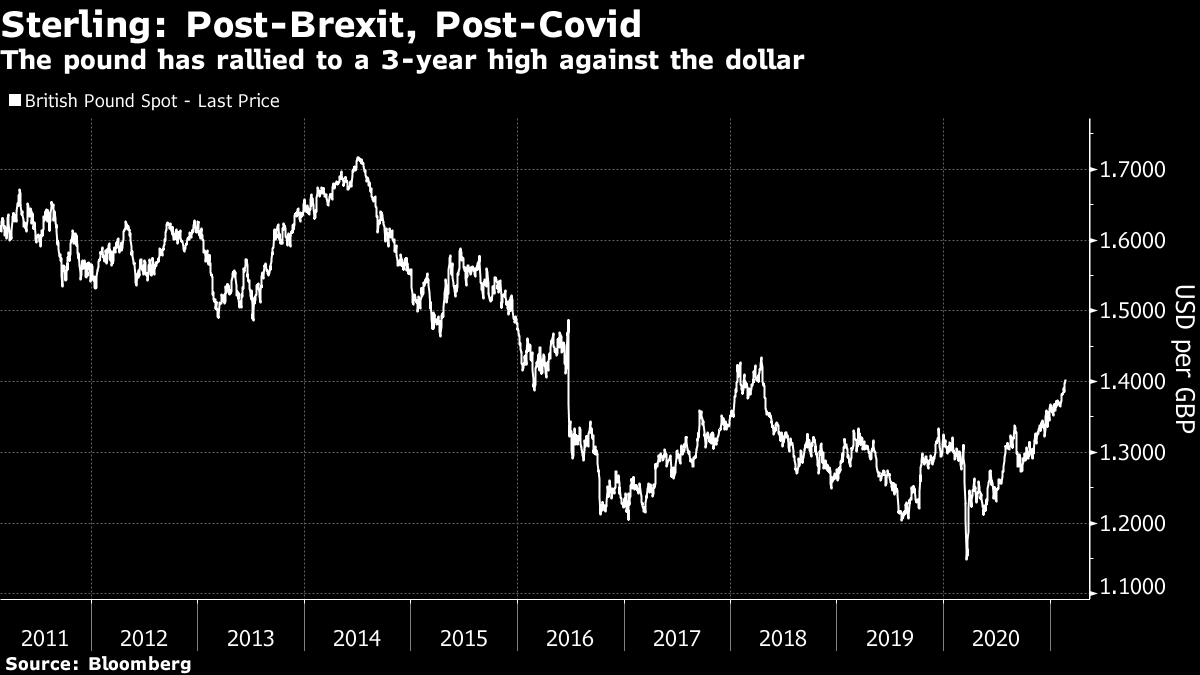

Referendum night in June 2016 gave the pound the biggest one-off devaluation any major currency has suffered in the past half-century of floating exchange rates. But confidence is returning. Last week, sterling topped $1.40 for the first time in three years. It is back up above where it came to rest on referendum night:  Does this mean that an opportunity has been missed, and the pound is no longer competitive? No, not really. Looking at the currency's performance against a trade-weighted basket (naturally dominated by the euro), sterling is still roughly where it was immediately after the referendum. It has been in a clear range ever since Britons decided on Brexit; the optimism of the last few weeks has brought it back to the top of that band.  While confidence is returning, which is important, the currency remains competitive, and has room to appreciate much further. Capital Economics Ltd. gives the bullish case for sterling as follows: - The pound has been behaving more like a risky asset than a safe haven one since the start of the pandemic. Indeed, the correlation between the FTSE 100 and the pound has risen sharply since the start of 2020. So even a small further rise in investor sentiment should benefit the pound.

- The rapid vaccine rollout in the UK has improved the economic outlook relative to its peers, especially in the EU. As a result, investors may start to favour UK assets over those elsewhere, putting upward pressure on the pound.

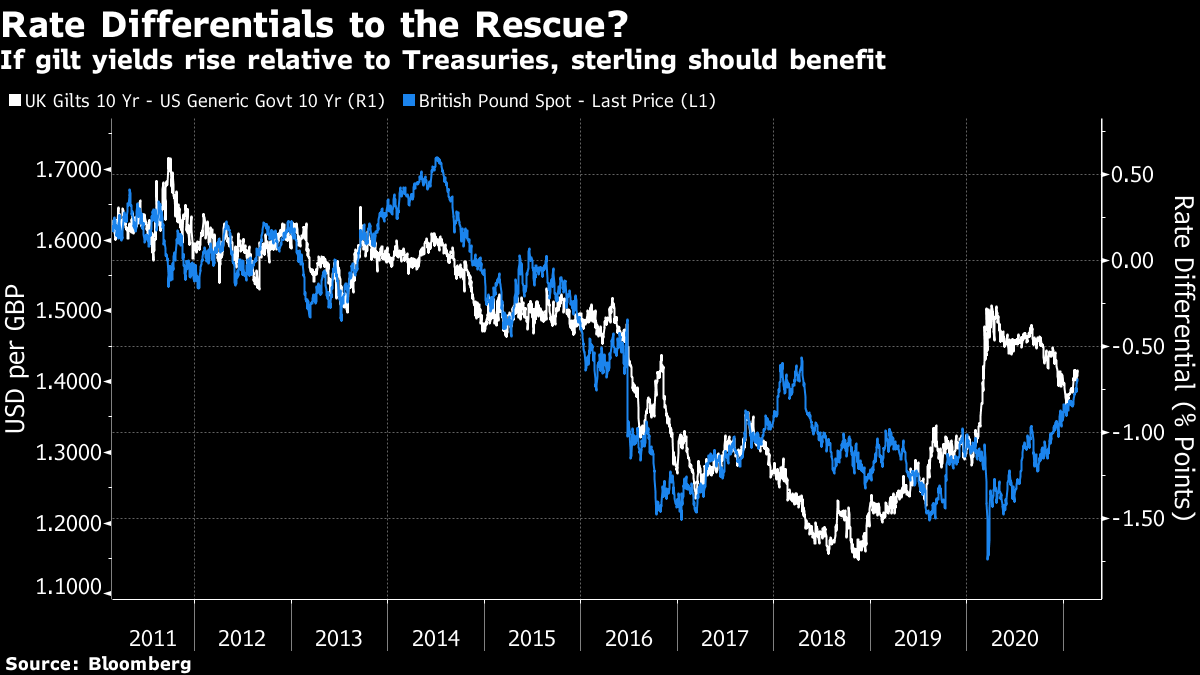

- The Bank of England has recently backed away from using negative interest rates and, based on our forecasts at least, won't expand its QE purchases. At the same time, the Fed and the ECB are likely to continue with their QE programmes for another year at least. This may push up UK rate expectations relative to those in the US and the EU, driving up the pound.

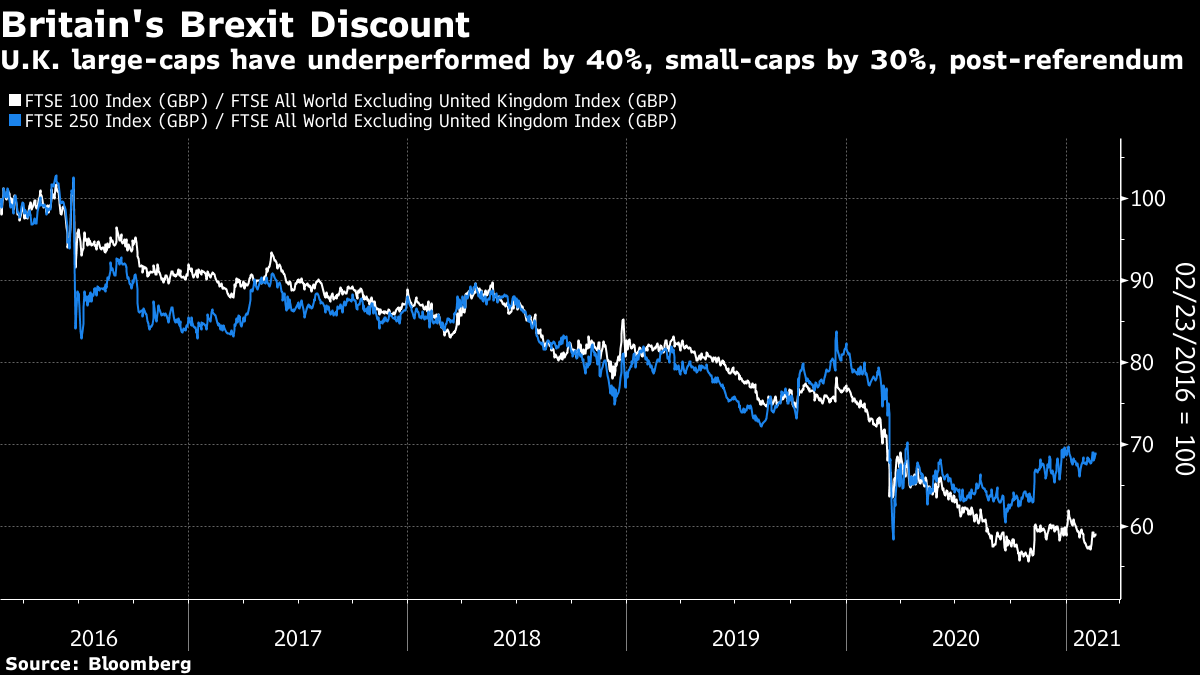

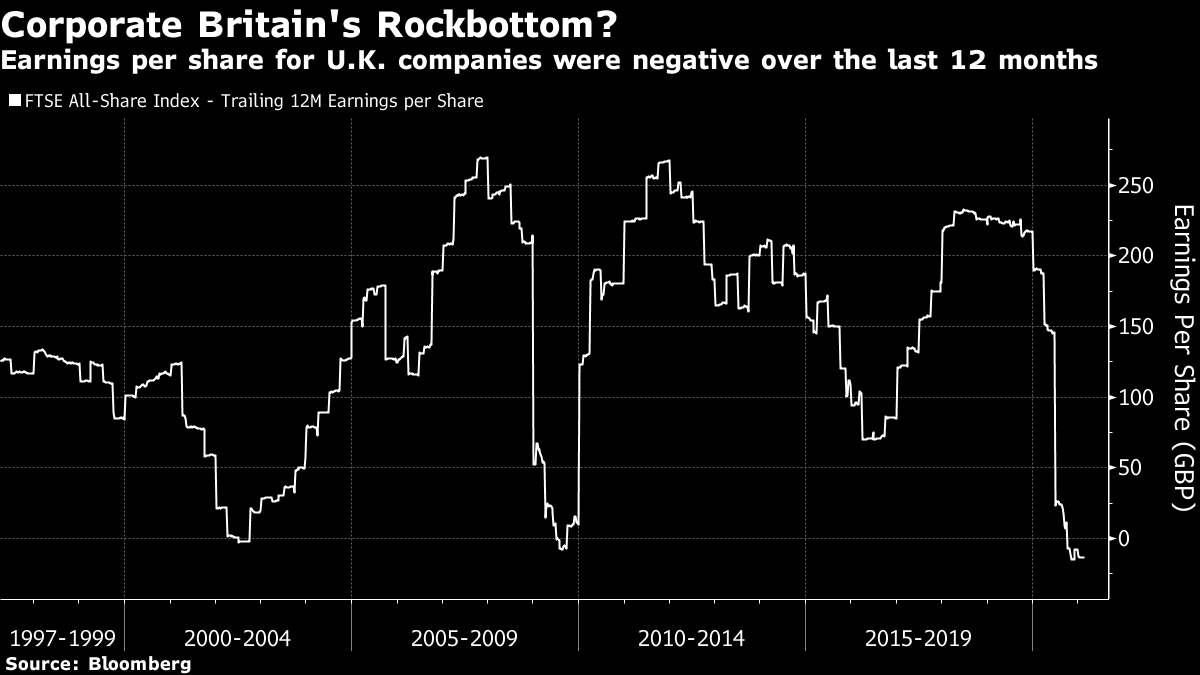

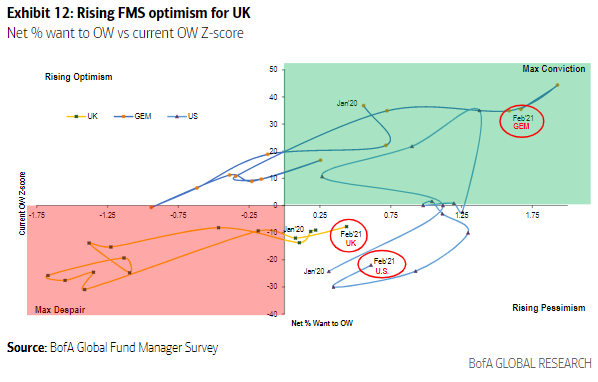

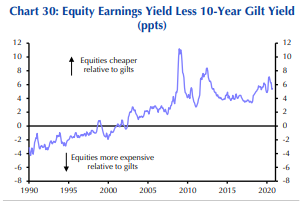

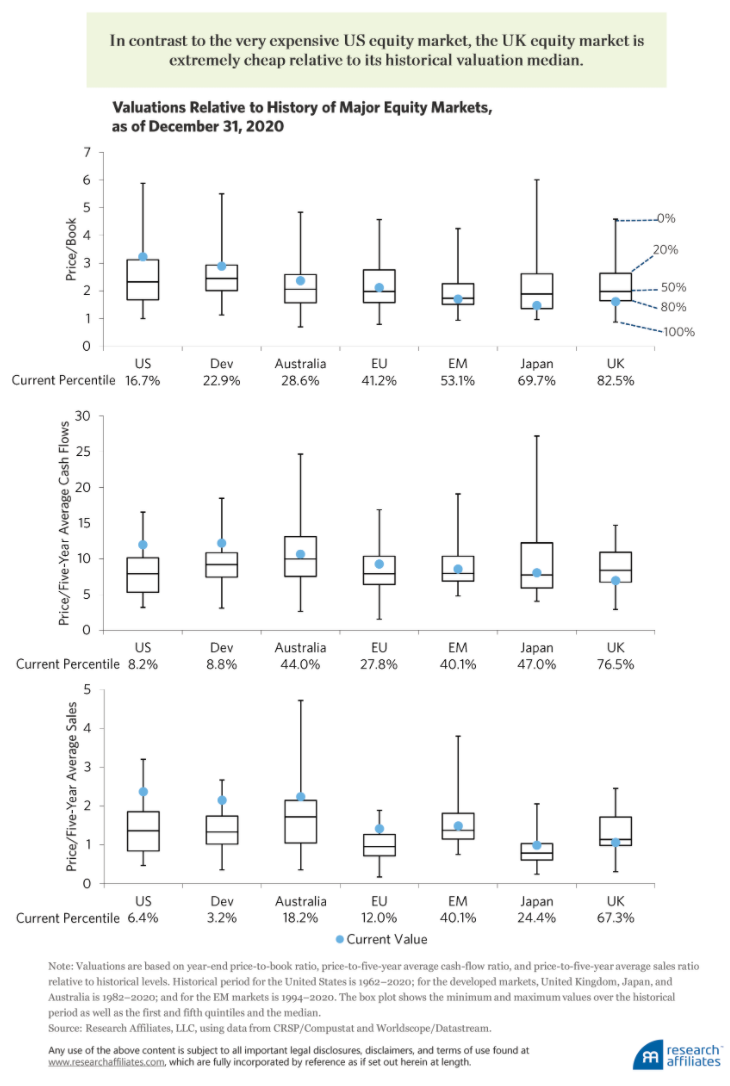

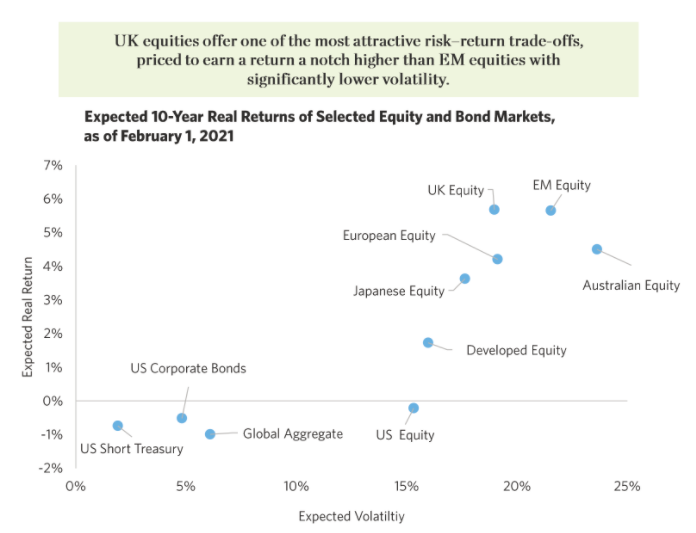

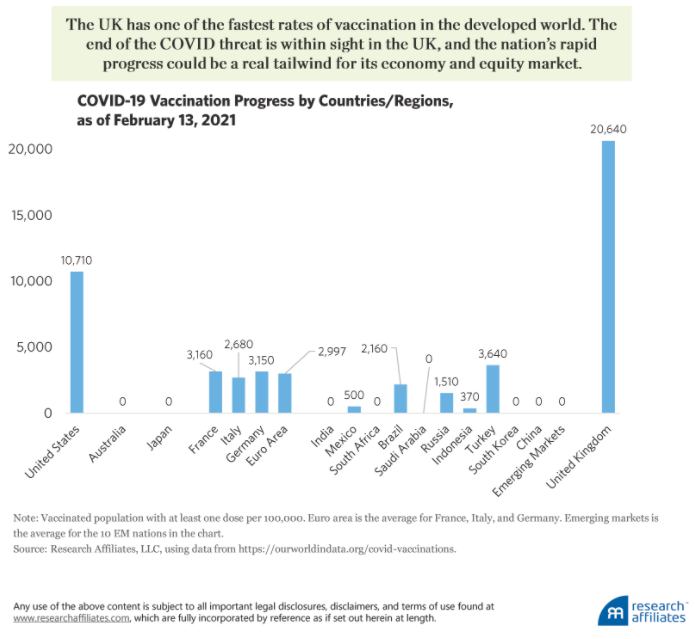

If we look at rate differentials, we can see just how much the latest sell-off was driven by fears over the virus, and the progress of Brexit deals. Gilt yields spiked much higher than Treasury equivalents last year, which should have sparked higher sterling. The exact opposite happened:  Why should we expect British rates to continue to give support to the currency? For a while, expectations were that the Bank of England would be aggressively dovish, with new waves of QE asset purchases to cushion the effects of the post-Brexit trading conditions. Nobody expects higher interest rates anytime soon, but the likelihood of more money-printing to keep the economy running is perceived to have fallen sharply. One reason is that Britain's inflation expectations remain stubbornly higher than in the rest of the world, in part because of the belief that cheaper sterling will lead to higher prices:  This puts some limits on the BOE that don't exist for other countries, such as the U.S., where the fast-growing conviction that reflation is upon us is a more or less unqualified positive. The sudden and impressive steepening in the U.S. yield curve in the last few weeks — with the spread widening between shorter and longer-term rates — is taken as a sign of growth, and of inflation returning to normal. It isn't, critically, taken as a reason why the Federal Reserve will need to tighten policy. With persistent inflationary pressure in the U.K., the belief is that a further reflationary trend would bring U.S. yields higher relative to the rest of the world, which would mean stronger sterling.  The stock market Equity investors' verdict on Brexit has been savagely and consistently negative. The following chart shows how the FTSE-100, including Britain's biggest multinationals, and the FTSE-250 of mid-caps, which tend to be more dependent on the U.K. economy, have performed over the last five years compared to FTSE's index for the world excluding the U.K. Both lost some 40% compared to the rest of the world in the four years from the referendum to the first wave of the pandemic — mid-caps have since recovered a bit and are down only about 30%. Whichever way we look at it, this is a massive vote of no-confidence in the U.K.'s decision to "take back control" from Brussels:  The question is whether this has now been taken as far as it needs to be or (ideally) too far. Britain continues to trade with the EU, on generally favorable terms, after all, and this is a massive discount to the rest of the world. If we look to corporate fundamentals, there are again signs that Britain has hit rock bottom. Earnings by companies in the FTSE All-Share index over the last 12 months have been negative. This shouldn't have happened in the first place; but it does suggest that the stage is now set for a strong recovery:  Is there any reason to expect investors will move toward the U.K.? If we look at sentiment among global fund managers, as measured by the regular monthly surveys taken by BofA Securities Inc., we find that the number of managers planning to go overweight in the U.K. is rising, but still has a long way to go. Emerging markets, darlings for a while, saw interest decline a little in the latest survey. This looks like a very positive environment for future flows into the U.K.:  Valuations The big reason for bullishness about equities is, of course, the extreme expensiveness of bonds. When fixed-income yields are so low, it grows that much harder to resist the charms of stocks. Gilts are supporting U.K. equities faithfully, as this chart from Capital Economics makes clear:  Beyond the argument from bonds, we can look at the valuation of stocks relative to their own history. It is here that the U.K. begins to look like a bargain - the Sale of the Century, or at least, as Rob Arnott, the valuation guru who founded Research Affiliates LLC, puts it, the "Trade of the 2020s." As he shows in the following chart, U.K. stocks look cheap relative to their own history, whether we look at price-book, price-average cash flow or price-average sales ratios. None of the other leading developed markets, or even the emerging markets, looks anything like as cheap by comparison:  Note that this valuation case makes no reference to bonds. Whatever you think of the bond market, if you're interested in buying stocks then British ones look cheaper than anywhere else, and American ones look expensive. The cheapness doesn't guarantee that U.K. stocks will rise in price, but it does greatly reduce the risk that they will fall further. That accords with intuition. After the five-year nightmare of the Brexit process, and the terrible year they suffered at the hands of the pandemic, British assets are on the floor. Research Affiliates's model for projected returns over the next decade shows the U.K. and the emerging markets as by far the most likely to rise. This accords with the intuition that both the U.K., with its many quoted resources companies, and many of the emerging markets should benefit strongly from reflation, which tends to bring higher commodity prices in its wake. But the U.K. is positioned for far less volatility than the emerging world — or than Australia, a resource-dependent economy that is also projected to go through much volatility.  Meanwhile, the U.S. stock market will, by Arnott's projections, be lucky to match inflation over the next decade. Vaccination Finally, value trades need a catalyst. There might have been one from the resolution of the Brexit uncertainty at the turn of the year. But the most potent catalyst is, in all probability, a vaccine. As the weeks go by, it grows ever clearer that the U.K. has managed to get the logistics of vaccination right (despite or because of its National Health Service) in a way no other large country has managed thus far. Arnott offers this chart showing British superiority:  It is fair to expect that this will allow U.K. economic activity to return to something like normal months ahead of the U.S., and in particular its neighbors on the other side of the English Channel and the Northern Irish border. Johnson is due to give a big speech on the government's latest reopening plan on Monday. This is causing great and understandable dissension; but the key point seems to be that the prime minister wants to be "cautious and irreversible" — if he gets it right, no stage of reopening in the coming months will need to be followed by a re-closing. Britain's vaccination successes should more or less guarantee that the country can restart earlier than anyone else. Johnson has shown a propensity to over-promise and under-deliver. The risk that he mishandles what should with luck be the final stage of the pandemic is real. But British assets are already priced to take account of that risk. There is reason to expect plenty of upside if he gets it right. Britain has been an embarrassing sight to behold over the last five years. The stage should now be set for a great rebound. Survival TipsThe wave of winter storms across the U.S., and the extraordinary crisis it caused in Texas, have shaken many of us. Survival in such circumstances is difficult. I can at least offer the best song I know about a winter storm causing power outage (indeed it's the only song I know about that): Power Out by Arcade Fire. You could also try listening to Stanlow by OMD, the only song I know about an oil refinery. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment