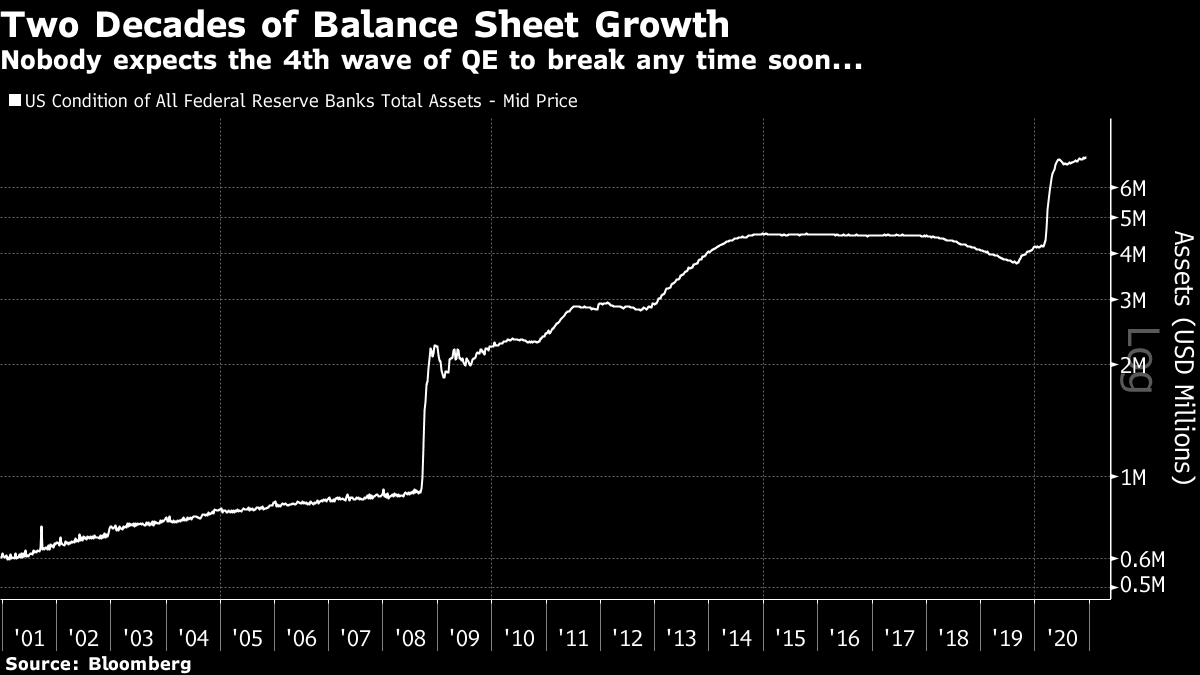

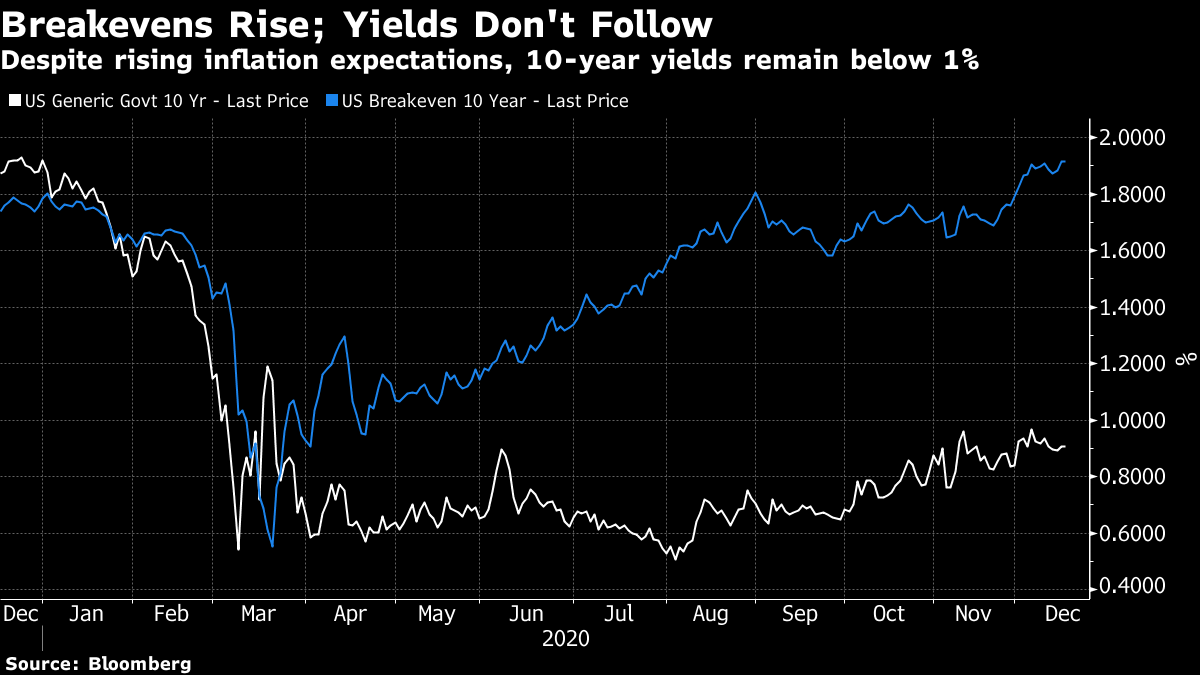

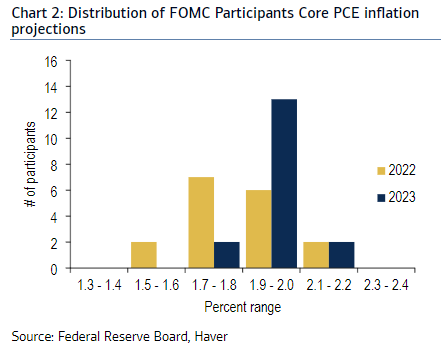

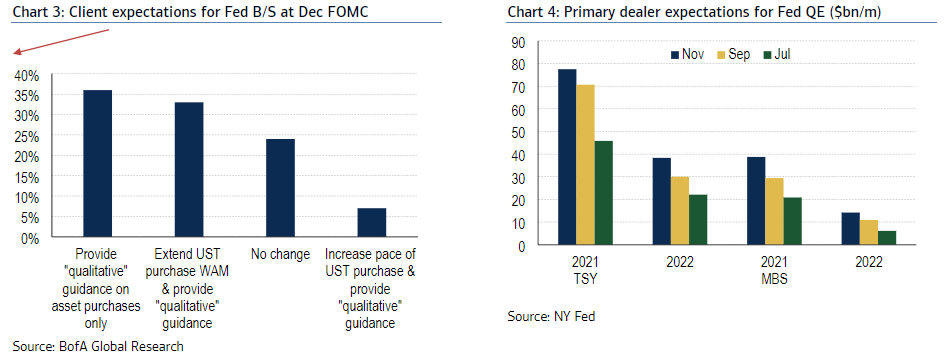

| Wednesday will bring 2020's last financial policy set piece, as the Federal Open Market Committee meets to set monetary policy, and then the Federal Reserve's chairman, Jerome Powell, faces the press to guide us. Despite growing medical optimism, he is under much pressure for action, and almost all of that action is likely to be painfully technical. Gone are the days when the Fed had effectively one monetary policy tool, its target interest rate. So, unfortunately, Powell is likely to take us all for one last trip into the thickets of monetary policy. There have been several developments since the last meeting, which came in the week of the election when no winner in the presidential race had yet been called. We now know (with almost total certainty), that Joe Biden will be president when the FOMC next meets, and that Janet Yellen, Powell's predecessor at the Fed, will be installed as the next Treasury secretary. Yellen is likely to be a) dovish and b) very much prepared to collaborate with the Fed (which is great news for the equity market, even if it may not be quite so great for the economy). A major fiscal boost now looks very unlikely, although Democratic victory in both next month's Senate elections in Georgia would allow for much more in the way of a spending splash — so the Fed is less likely to be able to hand over the baton to fiscal policy than seemed likely when the "Blue Wave" narrative was in vogue. We also now know that the scientific community has produced at least two vaccines which appear primed to bring the Covid-19 pandemic under control over the next few months, making the economic outlook unambiguously more promising than when the FOMC last met. At the same time, what will hopefully be the final wave of the pandemic looks certain to slow down economic activity significantly over the next few weeks. As for the market reaction, it has been positive, while hopes for reflation next year are about as strong as they could possibly be. When people in markets feel this positive, it's not surprising if financial conditions grow very easy. The Goldman Sachs US Financial Conditions Index, which is constructed as a weighted average of riskless interest rates, the exchange rate, equity valuations, and credit spreads, in proportion to their impact on the economy, is currently spectacularly easy — far more so than in the late 1990s, or at any point in the post-crisis QE era:  If people trying to raise money already have it that easy, it grows harder to see why the Fed is under pressure to act. It grows harder still when the size of the Fed's balance sheet is taken into account. What was in effect the fourth wave of QE wasn't quite as big as the one that followed the Lehman Brothers implosion, in proportionate terms. But it has still been a massive support effort:  How can conditions remain so easy when optimism is so great? That is a good question. Inflation expectations have now recovered all their losses during the deflation scare that accompanied the Covid shock in the spring, but nominal yields have made a much more muted recovery, meaning real yields remain deeply negative:  The remarkably somnolent 10-year yield, at a point when commodities and stock markets have already embarked on a reflation trade, raises the widespread theory that the Fed is already in effect engaged in "yield curve control" — a policy that the Bank of Japan adopted five years ago to target longer-term yields. And if we look at yield curves, comparing three-month and two-year yields to 10-year yields, we can see that both somehow seem to have foreseen the Covid-driven recession by inverting late last year, and that both have steepened sharply since then:  The steepening curve might be happening too quickly for the Fed's liking. The September projections offered by FOMC members for the future of core PCE inflation, the Fed's preferred measure, show almost no concern about an overshoot in inflation in the next three years. As the Fed is committed now to targeting average inflation over a period of time, it is prepared to accept increases above the official target of 2% for a while — which implies that it should see little need to tighten rates within the next three years (the chart comes from BofA Securities Inc.):  At his last press conference, Powell said that the Fed would "continue to monitor developments and assess how our ongoing asset purchases can best support our maximum employment and price stability objectives." This suggests that some recalibration lies ahead. The question is how the central bank will do it. The broad possibilities for the Wednesday meeting concern raising its asset purchases (which few expect and would look like an overreaction with markets already so buoyant), doing nothing (also unlikely given the alarm over Covid-19 and the lack of any move on the fiscal front since the last meeting), or one of two options. Either the Fed could give "qualitative" guidance on how it will adjust its purchases, with Powell offering some new vocabulary for everyone to interpret and some new conditions that might trigger any QE increase in future; or he could go for weighted average maturity, or WAM, targeting. Thanks to the catchy acronym, WAM is dominating discussion, even if it isn't quite as sexy as it sounds. BofA's survey of traders shows about a third think the FOMC will announce a WAM target on Wednesday — meaning in effect that it will try to extend the average maturity of the bonds it buys under the program, so that it buys more longer-term bonds and tends therefore to flatten the yield curve. The New York Fed's own survey of primary dealers finds that expectations for ultimate purchases have steadily increased throughout the year:  That is the sliding scale that confronts the FOMC. With no help as yet on the fiscal side, it needs to show that it can maintain the inflation goals laid out by Powell and his vice-chair, Richard Clarida. In a Bloomberg interview in September, Clarida made clear that "months of inflation above 2%" would be needed before provoking a response. The steepening of the yield curve could be seen as a test of that resolve. But with the monetary conditions so clearly loose, and the vaccine news so positive, it is hard to see why Powell or the rest of the FOMC would feel the need to commit themselves to yet more leniency, by laying down a target for WAM, at this meeting. That can wait. A plurality of rates traders appears to expect that we will get some qualitative guidance, or a new form of words for everyone to argue over that will tend to flatten the curve a little. On balance, they are probably right. We should brace for some very careful parsing of the Fed's words in its statement; and Powell will need to be very careful that he does not mis-speak. Survival TipsOne kind reader has alerted me to the death of an American composer whose music might just be perfect for the moment. Harold Budd, known as the "godfather of ambient music" died last week at 84, of Covid-19. Normally the term "ambient" when related to music is enough to give me a toothache, but Budd's influence was broad, and he had some great collaborators including the Cocteau Twins and Brian Eno. At this juncture, with a winter storm alert and a Christmas Covid shutdown in the immediate future here in NYC, ambience may be just what is needed. You might try listening to Sea, Swallow Me, made with the Cocteau Twins, or Late October, produced with Eno and Daniel Lanois. Alternatively, I was recommended The White Arcades, which on first listen is ethereal and calming, or the more assertive After the Night Falls, which Budd made with Robin Guthrie. And as this has put me in mind of the Cocteau Twins and their lead singer Elizabeth Fraser, it's an excuse to listen once again to Teardrop, her glorious collaboration with Massive Attack. It has a distinctive trip-hop beat coursing underneath, but listening to it now it's possible to hear Budd's influence. Rest in Peace, Harold Budd. And feel free to continue sharing ideas for this slot. I'm very happy to try to keep fostering community. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment