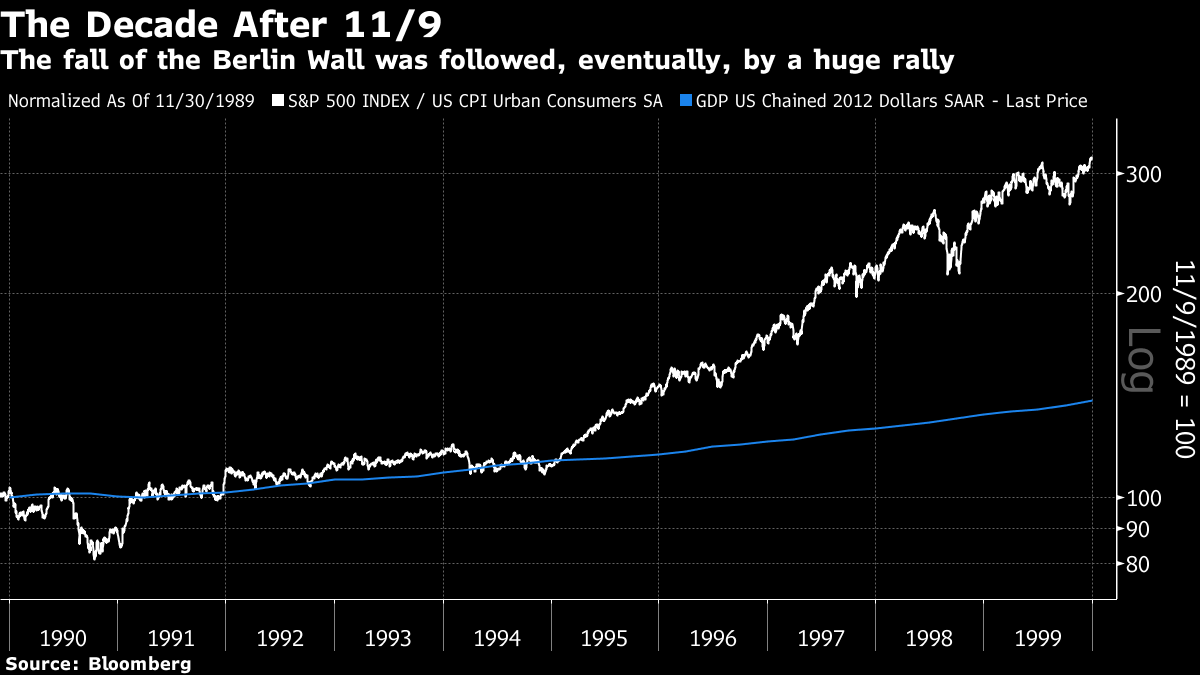

| It has been 20 years. Like most of us who were in Manhattan on Sept. 11, 2001, I find it difficult not to think of that day's events at the best of times. The focus on the 9/11 terrorist attacks over the 20th anniversary this weekend was close to intolerable. However, the topic can't be avoided, even for people who are primarily interested in finance. And it has gained greater urgency with the landmark coming just as the U.S. had pulled out of Afghanistan, ending the war it started as a direct consequence of 9/11. That withdrawal, appallingly handled, was accompanied by images painfully reminiscent both of the fall of Saigon in 1975 and (when young Afghans attempted to grip the side of an American transporter and fell to their deaths) of the figures who threw themselves from the towers 20 years ago. So let us discuss the long-running impact of 9/11 and other major historic events on markets and the economy, and try to understand the impact of the humiliating American abandonment of Afghanistan. To be clear, I like most readers find the impact of these events on dollars and cents unimportant compared to many of their other effects. But the financial consequences are still important, and profound. From the Wall to the Towers It's in the nature of historical turning points that there aren't many. We have a small sample size. But we can draw some conclusions from the impact of the two most important historical events of my lifetime — 9/11, and the fall of the Berlin Wall, which oddly enough happened on Nov. 9, the inverse of 9/11, in 1989. 11/9 ushered in what was dubbed the "end of history" at the time; 9/11 signaled the beginning of the U.S. war on terror. Both came as great surprises, and were accompanied by some of the most memorable and compelling images in human history — the fall of the wall, and then the fall of the towers. Oddly enough, the economic and market impact does have some similarities. After 11/9, nothing greatly changed for a while, stocks and the U.S. economy kept on growing at much the same rate — and then after five years, markets famously went ballistic:  After 9/11, the response was the inverse. A very negative market reaction was swiftly canceled out by determined fiscal and monetary stimulus. Then the S&P 500 lapsed into the last stage of its post-dot-com bear market, and its recovery was interrupted by the global financial crisis. In real terms, the S&P fell almost 10% in the decade after 9/11. GDP over that decade grew by just over 20% — barely half the increase in the 10 years after 11/9:  Naturally, many other things interposed to create the melt-up of the late 1990s, and the crises that hit a decade later. But neither decade would have been the same without 11/9 and 9/11. Both events contributed to the later financial ructions. Still, neither led to anything particularly dramatic in the shortest term. This wasn't because traders couldn't tell that something historic was afoot, but because it wasn't clear how those events would play out. With big shocks comes great uncertainty. The sense of triumph that the Cold War was really over took over in a big way by the end of the 1990s. Within Europe, it also led to the reunification of Germany, which was carried out on terms so generous to former East Germans as to spark a dose of inflation and then a slump, putting the EU's central economy out of kilter with the periphery for a generation. It also led to the euro, and the abandonment of the deutschmark, as this was the political price demanded by France for reunification of its powerful neighbor. London's rise as a financial center was aided by the rush to invest in eastern Europe; and the mistakes in opening the former Soviet Union led to the Russian default of the summer of 1998, the meltdown of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund, and the Federal Reserve's disastrous decision to pump in extra money and lower interest rates at a time when markets already looked infeasibly high. None of this was inevitable because the Berlin Wall fell. But none of it would have happened without 11/9. The one certainty when young Germans rejoiced as they hacked the wall to pieces was that things would never be the same. The same was true of 9/11. It would be absurd to say that the disaster was the cause of the GFC. But the lower interest rates in its wake helped to juice an already overheated property market. Both these events roiled the world with persistent uncertainty. The fall of the Berlin wall ushered in the collapse of the Soviet Union, German reunification and EU expansion. The second led to two intractable wars, in Afghanistan and Iraq. I argued on the 10th anniversary that 9/11 pulled the U.S. decisively off course. I stick to that judgment. What of Afghanistan? Plainly, the interminable U.S. war in Afghanistan is nowhere near as important as 9/11 and 11/9. It long since became obvious that it was a failure. The ascendancy of the Taliban increases geopolitical uncertainty a bit, but not by much; the Afghan economy is globally insignificant and nobody was relying on political stability there. That said, it was the gravest reverse for the U.S. on the international stage since 9/11. So how to rank its importance for investors? Louis Gave of Gavekal Research offered a thoughtful piece on this last month. He said: For investors, the question is which is the closest historical parallel. The flying helicopters and evacuated embassies recall Saigon in 1975. The speed of the humiliation evokes the 1956 Suez Crisis. And the images of the Taliban parading captured U.S. tanks and artillery pieces recalls the 2014 seizure of Mosul by Isis. Whether Kabul is a Saigon, Mosul or Suez moment will cast a long shadow.

To summarize, the Mosul moment proved a terrifying flash in the pan, and had little broader impact. ISIS was defeated within a few years. Saigon was the last and most painful debacle of a war that had already been abandoned as a hopeless misadventure. The travails of the 1970s would continue, but the Saigon disaster didn't stop ultimate U.S. success in the Cold War less than a generation later. Gave suggests the Suez Crisis, in which British and French pretentions still to be global powers collapsed in a matter of days, may be the best comparison for what happened in Kabul. China is rising as an alternative superpower. As he puts it: As Beijing expands its influence across Asia, its diplomats argue that while the US is in the region today, Asia may not always be a priority for Washington. In contrast, China has no choice but to be involved in the region. The US withdrawal from Afghanistan emphasizes this point. Imagine being a Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese, Indian or even an Australian policymaker today. After the weekend, would you be more, or less, likely to trust the US protective umbrella? And so, would you be more, or less, likely to try to patch up any differences and make friends, with China? If this is true for Asia, what about the Middle East? Or Europe?

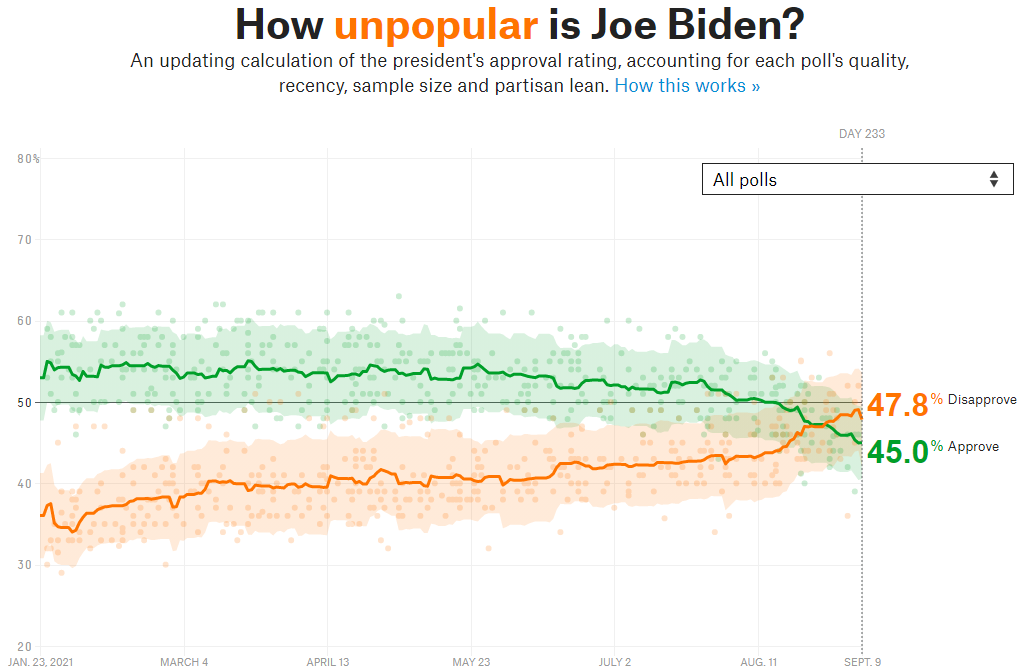

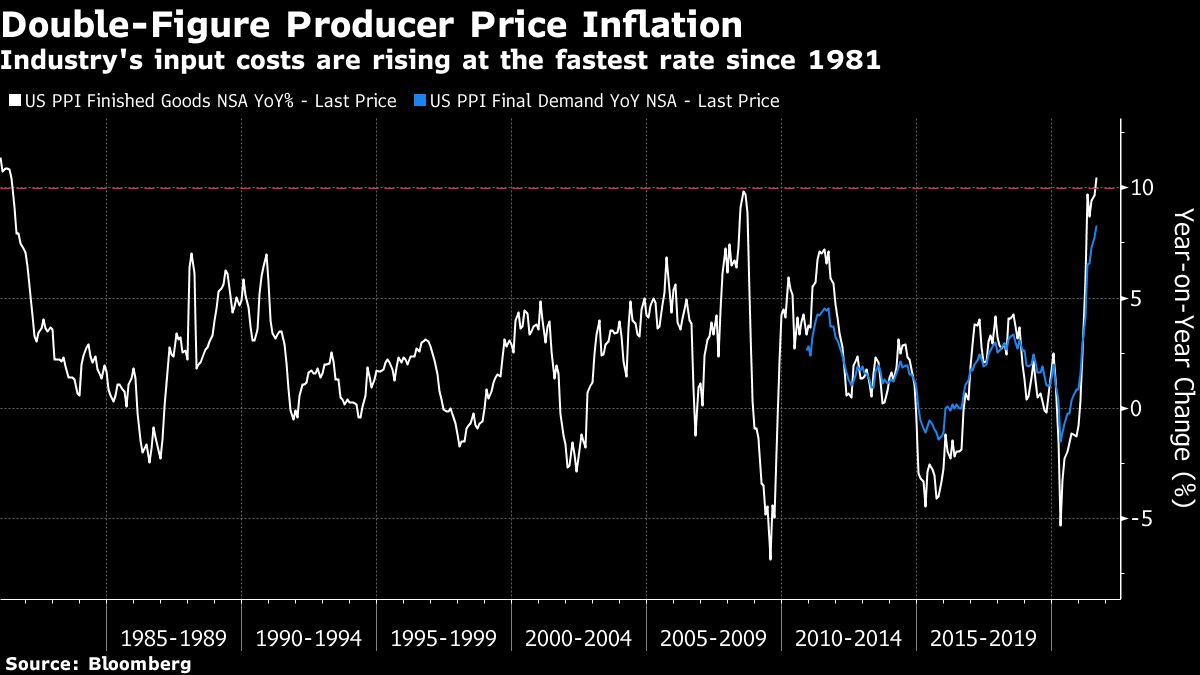

Gave fears that this was a Suez moment. Personally, I doubt this. We already knew that the U.S. was withdrawing from Afghanistan, and will now attempt to pivot to Asia. This isn't a sudden crisis in which two global powers reveal that they are no longer powers. Rather than Mosul or Suez, this is most like Saigon. Biden Is Looking Weaker For Saigon, the greatest impact was domestic. Gerald Ford lost his re-election bid the following year, although he had many other factors working against him, and came close to pulling off a victory. The Iranian hostage crisis inflicted a similar fate on Jimmy Carter four years later. And indeed, if we look at the running poll of polls kept by fivethirtyeight.com, Joe Biden's political popularity has taken a sudden and severe dip in the last month:  This could matter a lot. Biden has to decide whether to replace Jerome Powell at the Fed in the next few weeks; there are also likely to be major political set-tos over his attempt to raise yet another fiscal stimulus, over the ban on evictions, and over the federal debt ceiling. And vaccination mandates have, remarkably, become a huge political issue. Anything that weakens Biden in this environment will ratchet up political uncertainty, and increase the risk of a political accident that returns the economy to crisis. Afghanistan, and his often tone-deaf handling of it in the weeks since the Taliban takeover, has unquestionably weakened him. But is Biden's political situation irretrievable? A couple of past examples suggest that it isn't. In October 1983, suicide bombings in Beirut killed 307 people, including 241 U.S. military personnel. This disaster had no political cost for Ronald Reagan, who was re-elected in a landslide a year later. And in 1991, a coalition of forces gathered by President George H.W. Bush successfully expelled Iraqi invasion forces from Kuwait with startling ease compared to the fears of the preceding months. This spectacular foreign policy success didn't avert Bush's ignominious electoral defeat the following year. Foreign policy failures damage weak politicians. Skillful politicians, like Reagan (or maybe Barack Obama, who was re-elected after the humiliating attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi in 2011) can survive them. Biden looks like a Ford or Carter at present; much rests on whether he can prove himself a better politician than that. We update our inflation indicators tomorrow, just in time for Tuesday's download of official data on U.S. consumer price inflation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The latest number didn't look good. Producer price inflation in the U.S. is above 10% for the first time in 40 years:  Yes, the base effects are still very significant. If we look at inflation over the two years since August 2019, prices increased at an average annualized rate of 4.24%. Over the two years to August 2019, inflation averaged an annual 1.95%, so this still represents a significant increase, but nothing like as terrifying as 10%. It would be good if inflation proved to be transitory. Some will be relieved to hear that Paul Krugman of the New York Times is still on Team Transitory; meanwhile, you can see my latest Risks and Rewards chat with the mighty Lisa Abramowicz, in which we both tried to come to terms with whether this inflation really is transitory, here:  My only firm prediction is that the inflation debate won't go away after this week's data. I found the 9/11 anniversary weekend in New York difficult to handle, and I wasn't alone. I was in Manhattan 20 years ago; I was never in personal danger, and didn't lose anybody who was very close to me. I did, however, spend days reporting from the site, and did have to deal with the deaths of six professional contacts, two of whom I had come to regard as friends. In the city, everyone knew someone who had perished, and everyone had their own story. This was a catastrophe that almost exclusively afflicted those in the prime of their lives. Workers in the towers and the fire department left children and spouses behind. People depended on them. The fliers that festooned the city as desperate relatives hoped their loved ones would show up somewhere, mostly showed the faces of young men in family photos with small kids. 9/11 was a political event in many ways; it had political roots that need to be understood, and profound political consequences; and the death toll in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and in the world as the result of Covid-19 was much higher. Many people around the world had reason to be angry with the U.S. All of these things are true, but for those of us who were here, none of this changes the essential nature of what happened. Death and destruction suddenly poured out of a clear, blue sky. The city was marked forever. For those of us who aren't military combat veterans, this is as close to being under a war-time attack as we're ever going to get, and the trauma doesn't go away. Even the skyline is now a permanent reminder of loss and horror. Religion and its rituals come into their own at times like this. On Saturday a friend, not normally very religious, said a Kaddish (the Jewish mourners' prayer) for the eight people he had known who had perished at Keefe, Bruyette and Woods, a brokerage that had its offices high in the south tower. Once he told me this, I wished I had done the same. There's also much to be said for talking. New Yorkers don't generally have a problem with voicing an opinion, but a lot of 9/11 has had to be bottled. We went through the Kubler-Ross stages of denial, negotiating and anger, and we've seen the brief moment of unity dissipate into something much nastier. That's made it harder to treat it honestly. I suspect a lot of very basic, and very human, loss and grief has been swallowed along the way. I fully appreciate that many others around the world have suffered the same experience. I can see why this seems like self-indulgence from people who live in a great metropolis. But when we have a loss we do need to talk about it and share it. To the extent I have a survival tip, that would be it. Have a good week, everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment