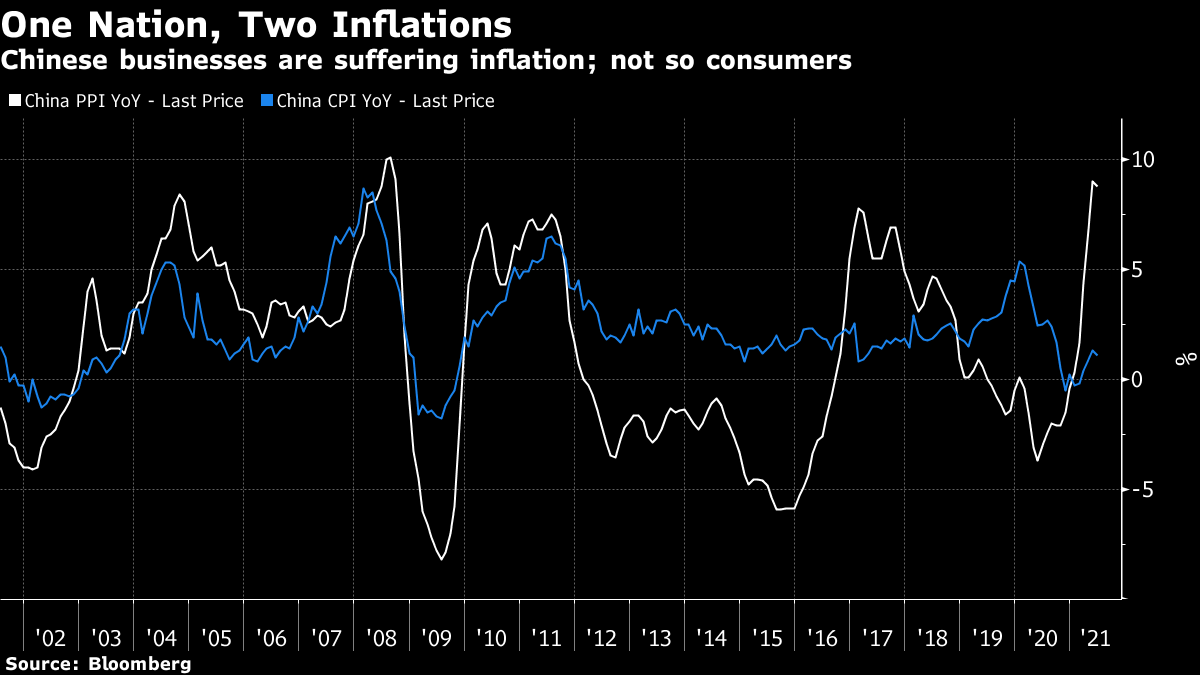

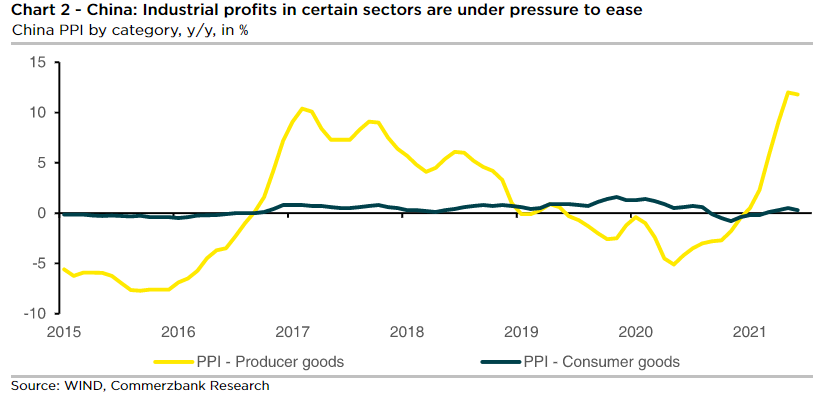

Two Nations, Two InflationsA news-starved market will soon have some more data to feed on. Tuesday brings U.S. inflation, which really matters these days, and then a range of banks will start reporting earnings for the second quarter. For a foretaste of what could be on offer, let's head to the world's other leading economy, China. At the end of last week, the People's Bank of China started what looked like a new easing cycle by cutting the amount of money banks needed to keep in reserve when lending. The U.S. is still dominated by concern over when and whether the Federal Reserve will start to tighten. There is a reason for this; while the U.S. braces for core consumer price inflation as high as 4% for the month of June, China had core CPI of just 1%:  That is quite a disjunction for two economies that share the same global economy, ever more fractiously. But China hasn't escaped price pressures altogether. While consumer inflation remains under control, producer prices, measuring the costs paid by companies, are registering their highest increases since the commodity spike that preceded the global financial crisis in 2008. While the two measures often differ, the present gap is the widest this century:  This implies a nasty profit squeeze for China's companies. Producers are battling a big rise in costs but they aren't, apparently, passing any of them on to customers. On closer inspection, it looks as though the cost inflation is restricted to big industrial items. A sectoral breakdown in China's PPI, in the following chart from Commerzbank AG, reveals a minimal problem for consumer goods:  The implication of such low consumer price inflation is disquieting. China is supposed to be roaring ahead as shoppers start spending and the economy benefits from demand that remained pent up during the pandemic. This cannot be encouraging. There are big differences between the two big economies, and China is hoping to finish the transition from a manufacturing-led economy to a consumption-led one, like the U.S. But it is still troubling that consumers are creating so little upward pressure on prices. For the rest of the world, the more important measure is producer price inflation, which stands to affect the price at which China sells goods into export markets. The clear reason for the high PPI is commodity price inflation. The following chart compares PPI with the Bloomberg Economics China PPI Inflation Tracker, which produces a monthly prediction based on a combination of four commodity price indexes. The Bloomberg tracker has been remarkably accurate over the last decade, and suffered its biggest overshoot last month:  Why might this have happened? China Beige Book International, which produces data on the Chinese economy, says this reflects concerted attempts by the authorities to squeeze out speculative excess in commodities. According to Shehzad Qazi, China Beige Book's managing director: Beijing's latest efforts to cool prices, from threatening speculators to unloading government stockpiles, have ignited a roaring debate over whether the Party can smother the rally. But this fundamentally misunderstands the policy mindset. Rather than trying to sustainably reverse price hikes, which reflect demand recovery and breakdowns in supply chains, the real goal is to drive the speculative "moneyball" out of Commodities.

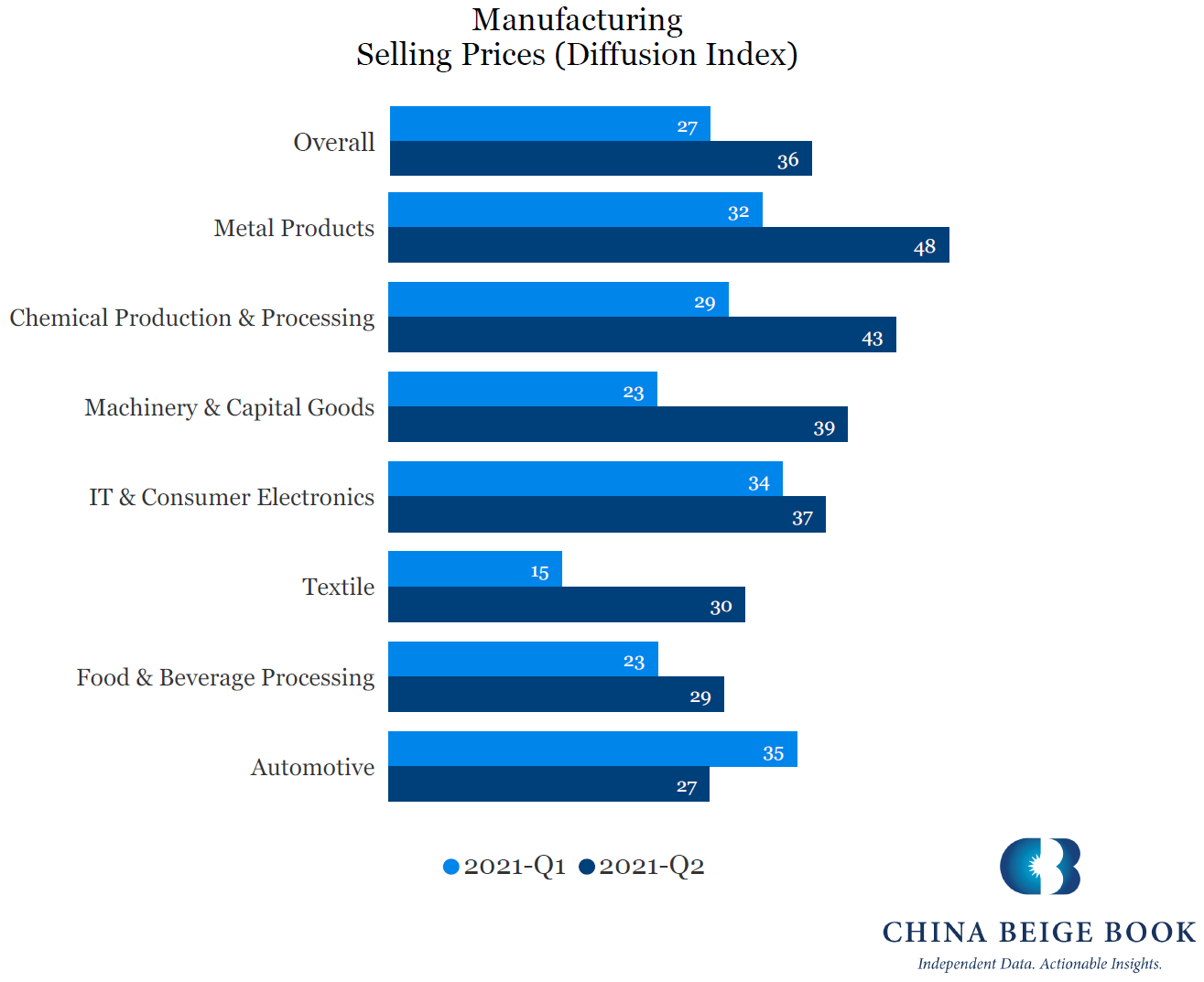

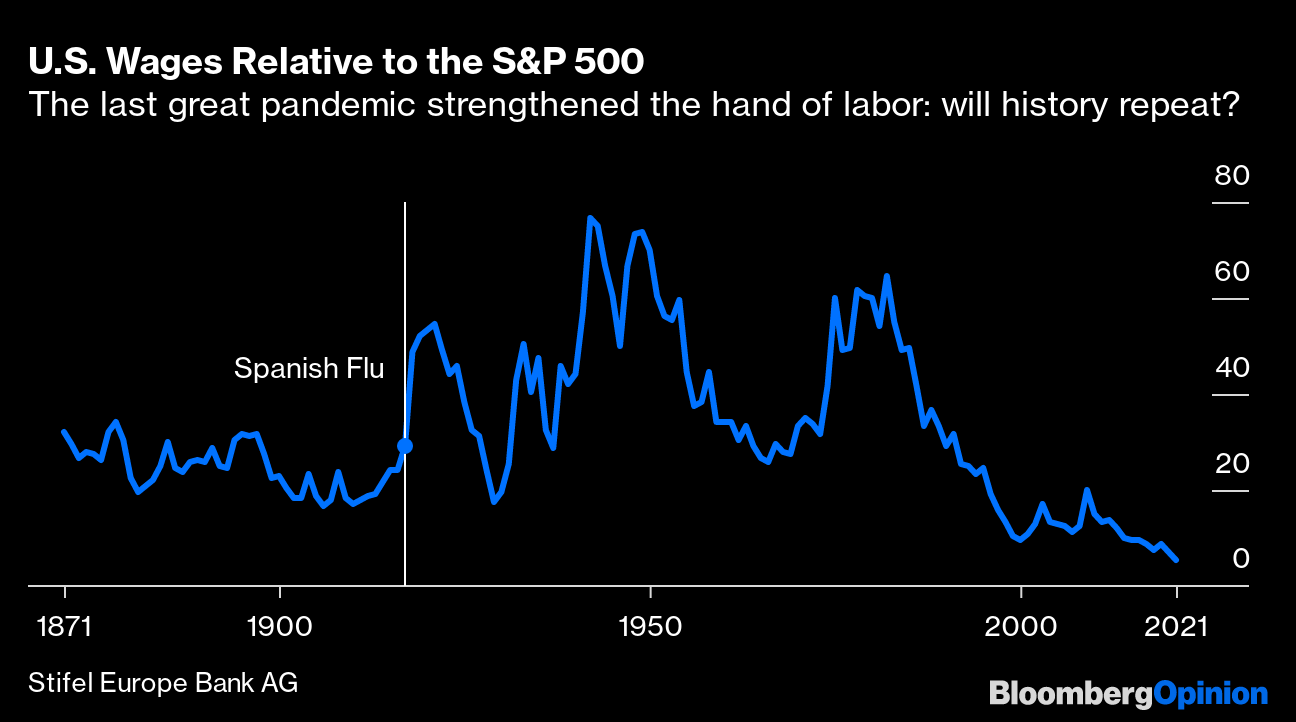

He also suggests that escalating producer prices don't mean China is exporting inflation to the rest of the world — or at least not as badly as might be feared. This chart shows China Beige Book's diffusion indexes for the different manufacturing sectors. Metals and chemicals are suffering the worst problems. Consumer electronics and textiles, the main exporting sectors, also register rising pressure, but have much less of an issue for the moment. So China is exporting inflation, but not that much:  There is an important readthrough for currencies. China's international competitiveness is a function of producer prices and exchange rates. To see how much the exchange rate is limiting its ability to compete in foreign markets, we need to look at relative levels of producer price inflation in different countries. Taking PPI into account, JPMorgan Chase & Co. produces the following index to show China's broad effective exchange rate, compared to a range of its biggest trade partners in real terms. China's most recent devaluation crisis came in August 2015, with its broad PPI-weighted exchange rate at more or less exactly the same level it is now. When it subsequently reached this level in early 2018, it was soon followed by a fall:  All of this suggests that the yuan may well now be as strong as the Chinese authorities can bear. It doesn't float freely, of course, and its peaks represent levels of tolerance among Chinese officials, rather than landmarks in market psychology. Thus, the chances are that weight will be put on the yuan to weaken from here. That would mean relative strength for the dollar, and would also at the margin imply lower import prices and lower inflation in the U.S. and Europe. I warned last month that China might effectively be exporting inflation to the U.S. Judging by the big gap in core inflation rates between the two countries, something along those lines has been occurring. But that changes if the latest shift in Chinese monetary policy, in response to what looks like a worryingly feeble consumer sector at home, really does mean that a weaker yuan is in the cards. In such circumstances, the prospect is that one source of inflationary pressure for the U.S. and Europe will reduce. That lies in the future. For June, the continuing strange effects of the pandemic on the Chinese economy will have prodded U.S. inflation upward. We will soon learn a lot more about exactly how much U.S. prices rose last month. Pandemics, Wages and Share PricesI wrote at the end of last week about research suggesting that past pandemics led to a strengthening of the negotiating position of workers compared to capital (even when excluding the Black Death and the Spanish flu of 1918, by far the worst outbreaks for which there is good documentation). Real wages increase in the wake of a pandemic. Tobias Woerner, an analyst for Stifel Europe Bank AG, offered a fascinating extra piece of evidence for this. As with all attempts to gauge the effects of past epidemics, there simply haven't been enough events comparable to Covid-19 to allow any statistically valid inferences. We'll have to settle for interesting anecdotal evidence. But the way the labor market, and the stock market, responded the last time around is suggestive. Using data from eh.net, the website of the Economic History Association (which I fervently recommend), Werner produced the following chart of the ratio of average U.S. wages to the S&P 500 going back to 1871 (which is when backdated calculations of the S&P start). When this line rises, the average wage buys more of the S&P, and when it falls it is harder to afford shares with the average pay. Fascinating to see, one of the sharpest rises on record came in the years immediately following the Spanish flu:  Yes, there were plenty of other things going on at the time; the First World War ended, and then the U.S. suffered a brief but nasty recession, to be succeeded by the roaring stock market of the Roaring 20s. But it's interesting to see such a sharp move in this ratio just when it might have been predicted, if pandemics indeed strengthen labor. Meanwhile, with the main stock indexes setting yet more records Monday as traders awaited their data fix later in the week, perhaps it's also worth noting that the reading at the end of last year was the lowest on record. In the last 40 years or so, price inflation has come under control, but stocks have grown far more expensive from the point of view of anyone hoping to buy them with the proceeds of a normal American wage packet. It's worth taking that on board as one of many signals that a rise in wages, at the expense of shareholders, might be no bad thing at this point. And my thanks again to Woerner for some very interesting research. Survival TipsFor those who need advice on surviving hard times, you can't do better at present than read the words of Marcus Rashford. For the uninitiated, Rashford is a privileged and by now very wealthy man of 23 who plays football for Manchester United and England. He has already been made a Member of the Order of the British Empire, or MBE, for his campaigning work to ensure that children who would normally receive free school meals were fed during the pandemic, and has made clear that his campaign to end child food poverty still has "a million miles to go." He is also Black. And he has the unfortunate distinction of having been the first England player to miss a penalty in the shootout that culminated in victory for Italy and defeat for England in the final of the European Championships at the weekend. Since then, Rashford's social media accounts have been full of racist abuse (as have those of the other unsuccessful penalty-takers). A mural of Rashford in his home neighborhood in south Manchester was defaced with racist graffiti. All of this is appalling, and while it represents the actions of a minority hiding behind anonymity it must be excruciating for him. You can find Rashford's social media post responding to all of this here. They are the words of an honest, decent and very brave young man. He's a remarkable individual who will survive this; and he's an example to us all. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment