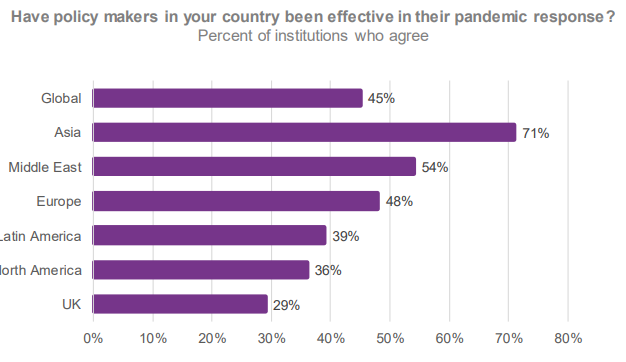

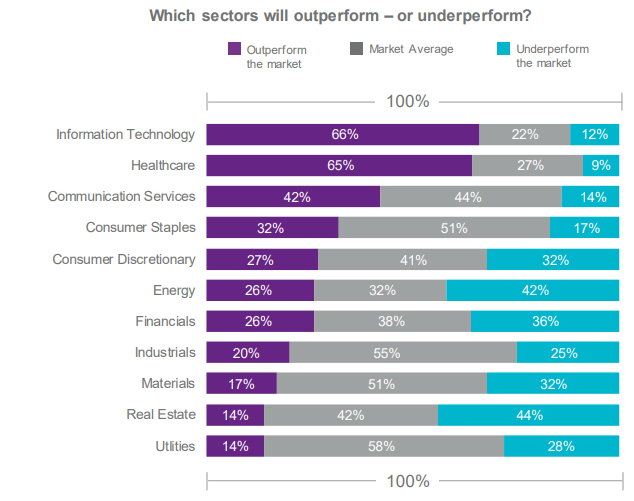

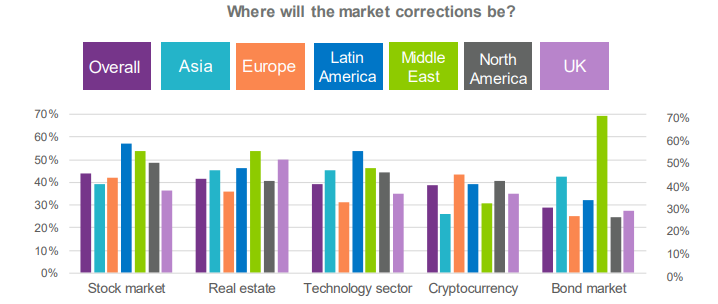

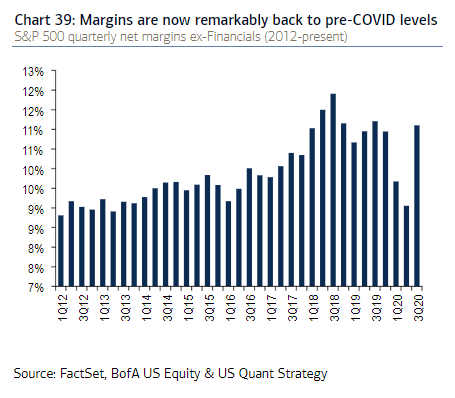

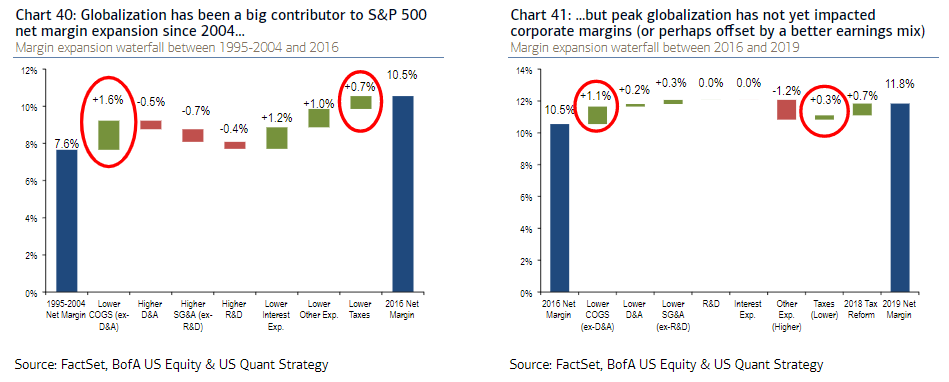

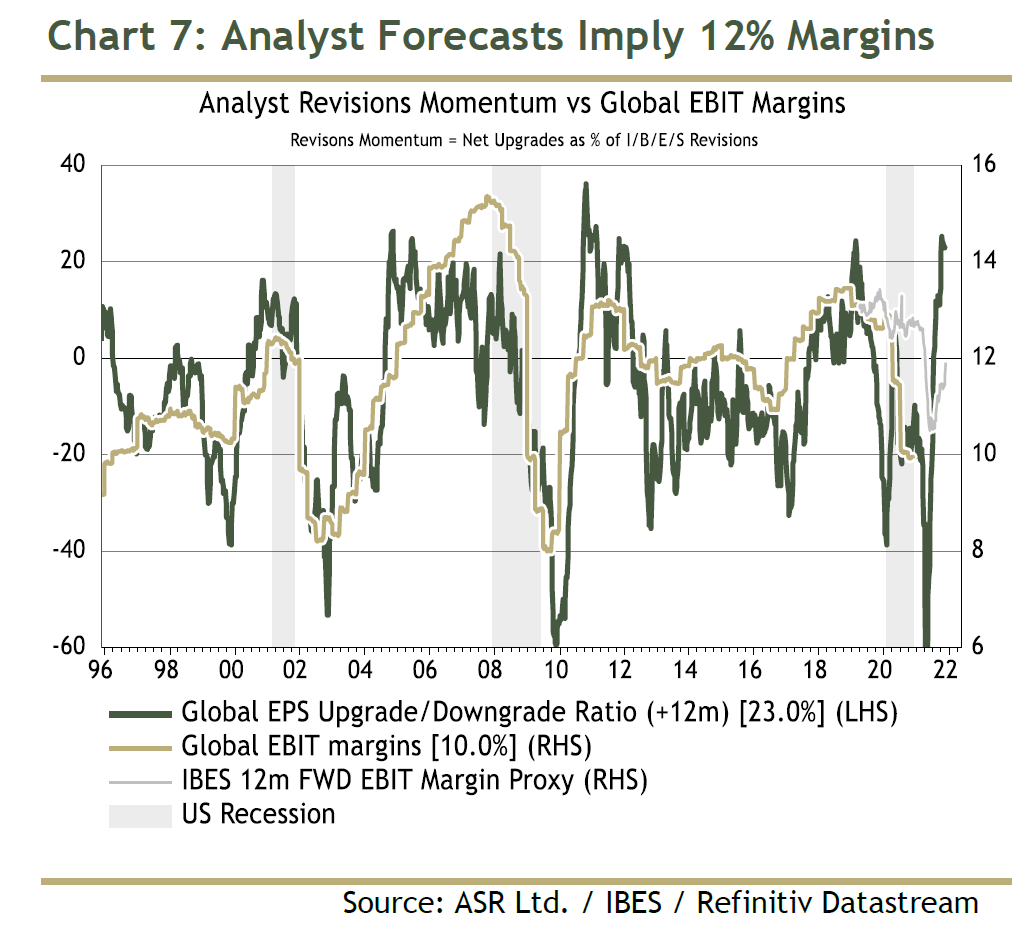

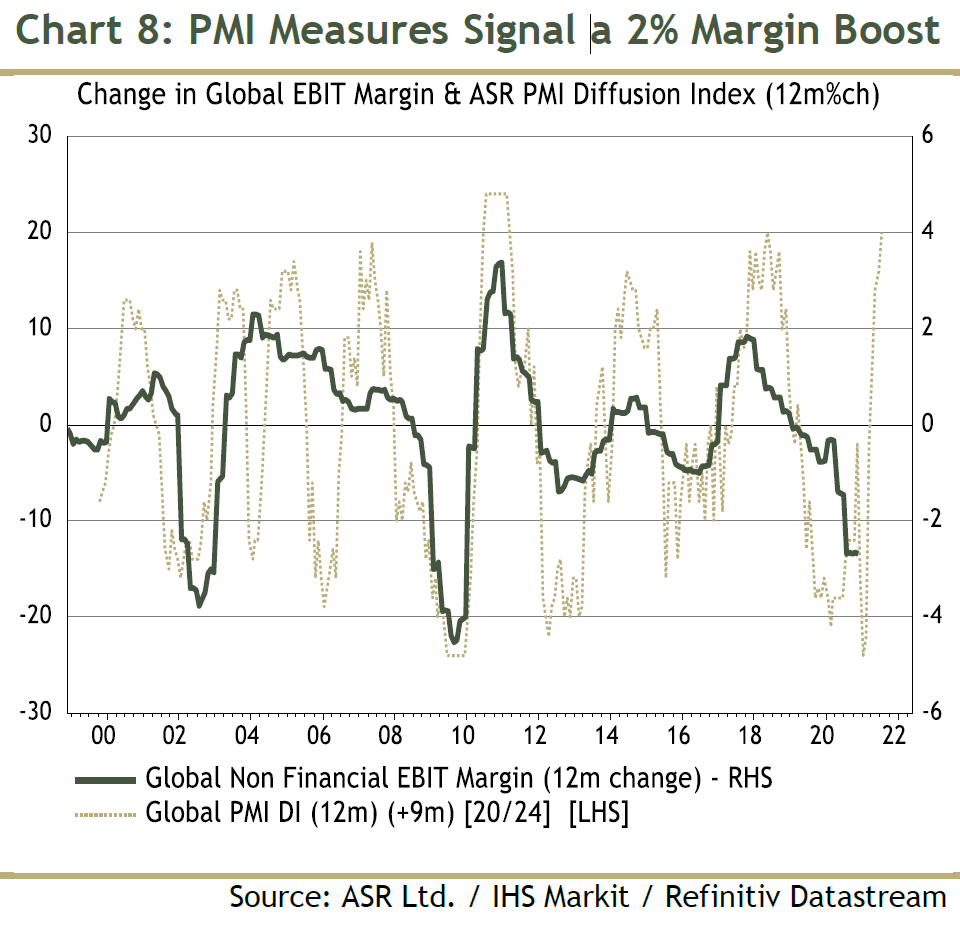

Big Money BearsWe are in the presence of yet another stock market record. This has been achieved, as many have observed, despite continuing awful conditions for the economy and society. That implies great expectations for the future. Only the round of predictions for 2021, now in full sway, gives only partial backing for that. Big institutions are still cautious. Last week, I highlighted a survey of extremely negative pension fund managers, produced for Amundi Investment Managers by the U.K. consultancy CREATE-Research. Now I have the results of a similar global survey of institutions by Natixis SA, which interviewed 500 managers from pension plans, endowments, insurers and sovereign wealth funds from around the world. Of these, 79% don't expect GDP to have recovered to its pre-Covid levels by the end of next year, making them more bearish than typical sell-side researchers. Asked for their expectations on broad trends for next year, it looks surprisingly similar to this year. There is a belief in a rotation toward value, but that co-exists with a belief that geopolitical tensions will worsen, amid rising social unrest, as democracy weakens. Both socially and economically, the people running very large institutions plainly believe the market is ahead of itself in expecting the effects of the pandemic to soon be vanquished:  This isn't surprising because most of them think that their governments have failed to do an adequate job of controlling the pandemic, although these numbers vary widely. In Asia, 71% think their countries have dealt with the virus effectively, while in the U.K., 71% think the opposite. These numbers largely follow the outcomes, but show that the pandemic is perceived as having revealed problems with governance:  As for the sectors that they favor, there is little institutional belief in a true rotation. Internationally, the sector most widely expected to beat the market next year is still technology, despite its extraordinary success in 2020. Projected losers are in line with the losers this year, and include a range of cyclical sectors; institutions don't believe in a cyclical upturn, even if the commodities market (followed to an extent by the stock market) is betting on such a thing:  Given all of this bearishness, it isn't surprising that the institutions are also braced for market corrections in 2021, with Latin American respondents expecting them in virtually every sector. As a correction is usually defined as only a 10% move from peak to trough, it isn't spectacularly bearish to brace for at least one in the course of 12 months. But again the picture is that those running big institutions, and less close to the excitement and animal spirits of the markets, are much less sanguine about the prospects of a full recovery from the pandemic in 2021 than the majority of the fund managers and investment bankers they hire:  In a sense, this is good for markets. Plenty of people, including some very powerful investors controlling large pools of money, don't believe in the rally. That implies there is plenty of room on the bandwagon. But the confidence that has helped markets to reach records still looks to be fragile. Growth at the MarginsOne of the great mysteries of the last decade has been the stubborn strength of profit margins. Over much of previous history, they had seemed to be one of the most reliably mean-reverting series in finance — a phenomenon that many attribute to the tug of war between capital and labor. When times are good, labor's negotiating position is stronger and it negotiates a bigger share of the pie in wages, which brings margins down, and so on. The summer of 2018, following the big corporate tax reform at the beginning of the year, did seem to have witnessed the beginning of a reversion to the mean. As the following chart, taken from the 2021 preview recently published by BofA Securities Inc.'s U.S. equity strategist Savita Subramanian shows, S&P 500 net margins topped and then began a steady fall, until the second quarter of this year. But remarkably, the net margin for the third quarter is right back to its pre-Covid levels. It is below its peak, but still far higher than many of us would have thought likely a few years ago:  Profits depend on the volume of economic activity, and on the margins that companies can extract from it. A cyclical revival in the economy should, all else equal, help to revive profits. If, following the institutions polled by Natixis, we can't trust that economic recovery, then companies will need to keep their margins at these levels. That doesn't imply good things for employees who were hoping that their wages were at last going to start rising. But even if companies can continue to keep the lid on union pressure, there is another issue. As seen above, we are braced for a further retreat of globalization, Biden or no Biden. Globalization, or the outsourcing of labor costs to China and other developing markets, has had much to do with the steady expansion of margins in recent years. That shows up primarily in cost of goods sold, and in the savings in taxes that companies can make by moving facilities offshore. As Subramanian shows in these charts, which break down the change in margins into their constituent effects, any retreat for globalization hasn't yet had any negative effect:  If margins can somehow continue to widen, that would be a potent sign that we can have at least some faith in stock markets, which seem to have lost touch with lived reality. And a study by Absolute Strategy Research of London does provide some positive leading indicators that suggest margins could widen. When analysts' momentum is improving (meaning upgrades are exceeding downgrades), then over the following 12 months EBIT margins tend to improve. Following their recent peak of 13.5%, Absolute Strategy suggests that global margins could get back to 12%:  Another good leading indicator for margins comes from purchasing manager indexes. As Absolute Strategy shows in the following chart, these sentiment surveys have taken off of late, implying that margins can gain by about two percentage points:  How rosily should we view the picture? There are still concerns. This recession has been dominated by the services sector, so the normal industrial leading indicators might not help so much. And ultimately, the greatest issue comes back to the pandemic and the speed with which a vaccination campaign can return us to our normal lifestyles. There are some difficult months to be negotiated yet. Beyond that, there are political concerns. To quote from Absolute Strategy: The coming six months should see a strong recovery in EPS growth and margin recovery which will favour the continuation of the recent rotation into value vs growth. Beyond that, however, margin expansion will be increasingly challenging, especially if policy makers begin to rein-back on their fiscal easing and the Global economy settles back into a muted economic cycle.

Increasingly populist Governments could also look to boost labour market shares at the expense of profits once recovery is assured.

And as the pension managers polled by Natixis make clear, popular discontent is an ever more alarming issue. For the very long term, it might be better for margins to take a medium-term hit, and for more of revenues to go toward labor rather than capital. It would be best not to rely on profit margins to continue to defy reversion to the mean. Survival TipsChristmas is almost upon us, and with it comes Christmas music. I just received this rather nice card, in the form of a Christmas play list from Blenheim Partners. There are hundreds of songs on here, and it's a lot of fun to explore them. My greatest quibble, as you might guess, is that most of the music is awful. I didn't know, for example, that Destiny's Child had done a Christmas song. Surely, it's the worst thing Beyonce ever did. As Tuesday was John Lennon day, let me direct you to Happy Xmas (War Is Over), and warn you not to bother with the execrable Robbie Williams cover version, or the one by Celine Dion. Other gems I perhaps wish I hadn't discovered include Sinead O'Connor's talents wasted on a cover of Silent Night, and a version by Blur of The Wassailing Song, a traditional English carol I've sung many times. It is at least quite funny that it's produced by "Gold, Frankincense and Blur." A cursory examination suggests that the prize for awfulness should go to Billy Idol's version of Jingle Bell Rock. (He was actually relevant at one point.) But I'm sure there are other viable candidates. As for the good stuff, British people of my generation still unfailingly see beauty in Band Aid. And then there are one or two seriously good songs that were big hits at Christmas. This one makes me think of Christmas, from 1975; and so does this one, from Christmas 1981. And Lennon's friend Paul McCartney had what was amazingly his biggest ever hit in Britain with this song from Christmas 1977. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment