Warning: Networking Can Be Bad For Your Wealth Big institutional investors spend lots of time and money searching for fund managers to run investment mandates. Long competitions, usually overseen by actuarial consultants, culminate in "beauty contests" where a shortlist of between two and five prospective managers make their pitch personally, usually aided by copious Powerpoint. I argued last week, citing a new paper by Richard Ennis, that this work is wasted. Institutions tend to hire too many different investment managers, ending with results barely distinguishable from a broad index. I now learn that it's worse than that. A new paper from the Swiss Finance Institute by Amit Goyal of the University of Lausanne, Sunil Wahal of Arizona State University

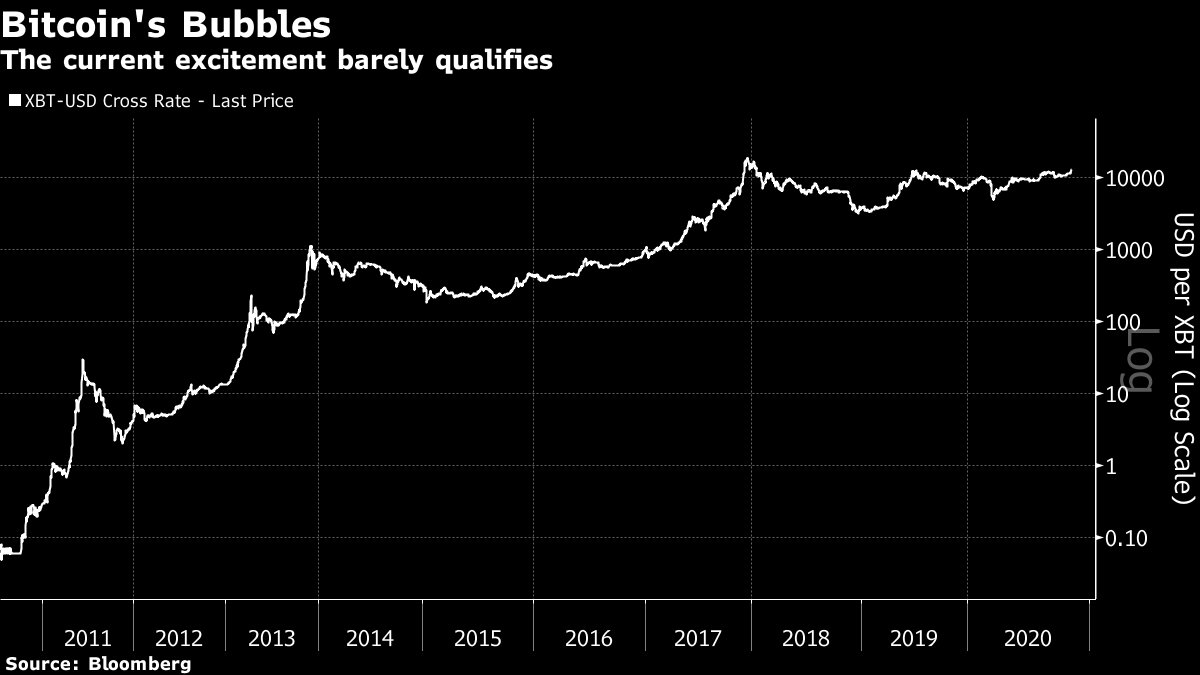

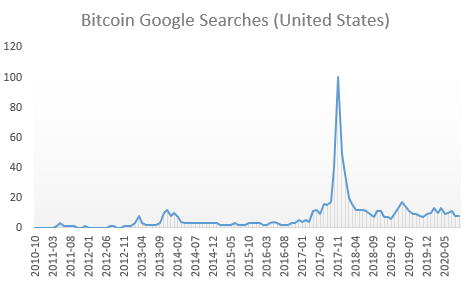

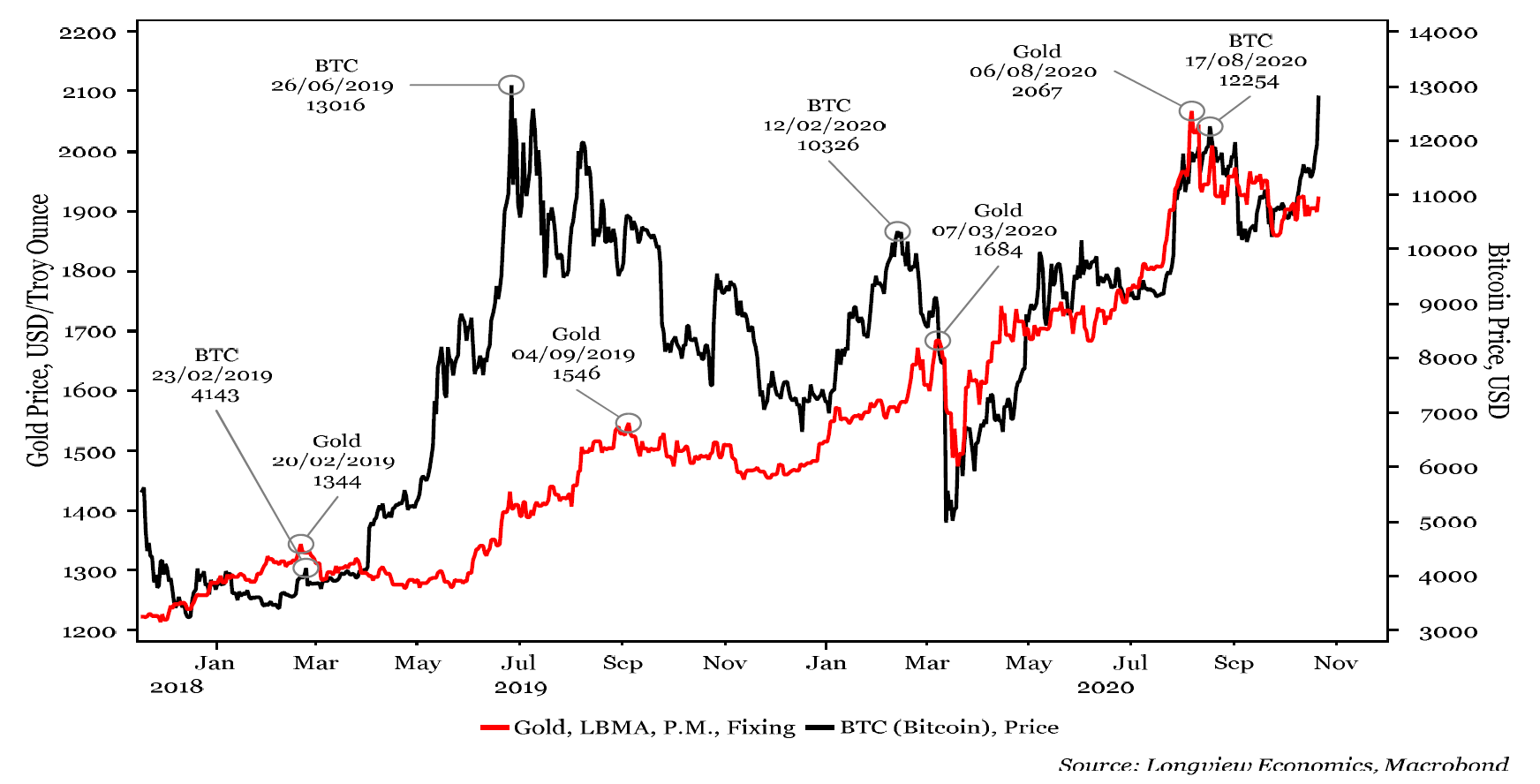

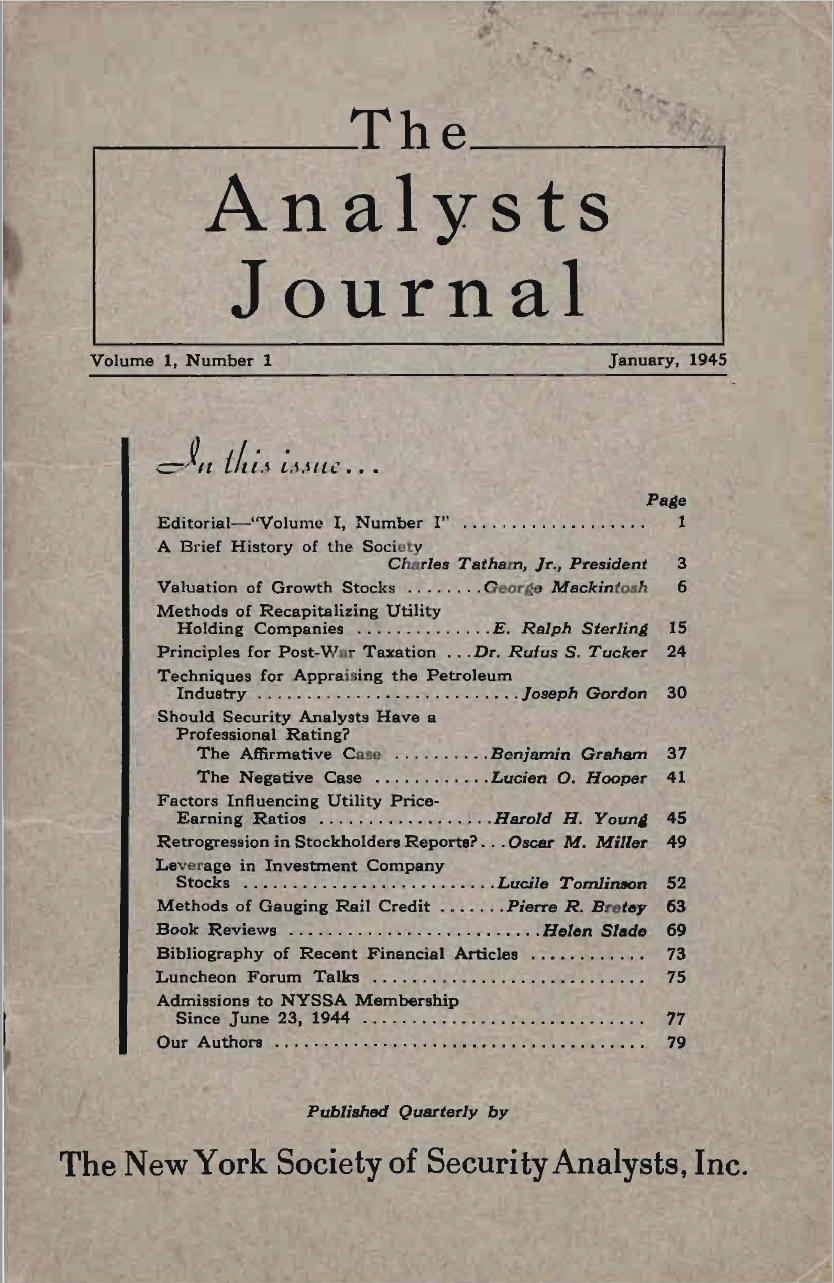

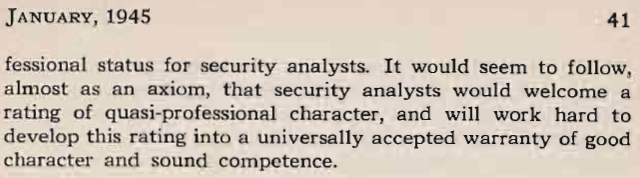

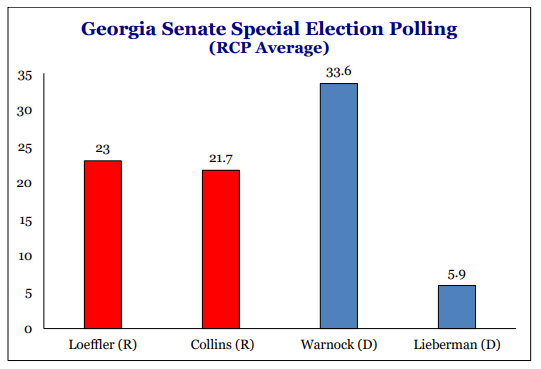

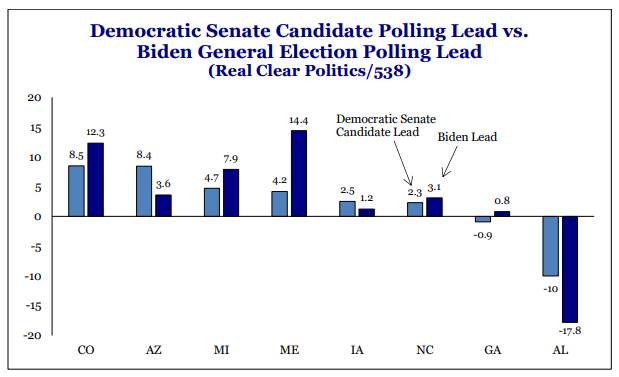

and M. Deniz Yavuz of Purdue University, called Choosing Investment Managers, looks at how the outcome of these beauty contests is affected by prior personal connections. Investment management tends to be a small and clubby world, and it turns out that club members tend to do well. With the sole exception of past returns , nothing is likely to help a candidate win a beauty contest more than already knowing someone on the hiring committee. This is the damning conclusion: Two factors play an influential role in choice: pre-hiring returns, and pre-existing personal connections between personnel at the plan (or consultant advising the plan), and the investment management firm. Post-hiring returns for chosen firms are significantly lower than those for unchosen firms. The post-hiring returns of firms with relationships are, at best, indistinguishable from those without relationships, and often significantly worse. While relationships are conducive to asset gathering by investment managers, they do not appear to generate commensurate benefits for plan sponsors via higher gross returns or lower fees. The research involved a huge and painstaking exercise in data sifting. The study involved nearly 7,000 decisions made by 2,005 global plan sponsors, who delegated more than $1.6 trillion in assets to 775 unique investment managers between 2002 and 2017. As mandates tend to be highly prescriptive, the total potential field of candidates was rarely more than 100, and often much smaller. Judged by past performance, funds in the top quartile for their strategy had a 30% better chance of being chosen than those in the bottom quartile. For data on prior relationships, they used a firm called Relationship Science. It found that managers with prior connections to the institutions (generally meaning serving as colleagues or on boards together) were between 15% and 30% more likely to be selected. They were also more likely to win the job if they had links with consultants running the contest. For the first three years after being hired, winning investment managers returned 0.85% less per year than their peer group. At the very least, the authors say, "these results suggest that plan sponsors have no discernable selection ability." They tested whether personal connections made a difference three ways. First, they looked at the difference between hired managers and alternatives when both had connections — remarkably, the winners performed worse than their rivals by 1.12% per annum. Second, they looked at whether investment committees did any worse at choosing between managers with no connections — and found no statistically significant evidence that they did. Third, they looked at connected versus unconnected winners: the unconnected managers tended to do better, although there were big variations. The evidence that personal contacts get in the way of hiring investment managers seems overwhelming. What should we do? To start, we could at least reduce the scale of the money and time wasted by cutting the number of mandates each institution awards, as Ennis proposed. Beyond that, a "robo-adviser" to replace investment committees might make sense. If we don't want to put that much trust in the machines, maybe anyone with prior links should be required to declare it and recuse. Failing that, discussion after the beauty contest could be minimized and all votes taken by secret ballot. This would reduce the tendency toward groupthink. As it stands, the evidence is that networking yields great returns for investment managers trying to maximize assets under management. It is a terrible money-loser for big institutions, and their clients. ICYMI Bitcoin is enjoying its first ever stealth rally. Since its epic boom and bust over Christmas and New Year at the end of 2017, the best-known cryptocurrency has been generating much less excitement. But it has now reached its highest in almost three years. It has gained more than 160% since the bottom in March and quadruped from a late-2018 low:  Over its brief history, bitcoin has tended to go ballistic every three or four years. This isn't anything like that, yet. Viewed on a log scale, recent activity doesn't compare with the bubbles in 2011, 2013 and late 2017:  This rally has also been accompanied by minimal interest in the world at large. Three years ago, bitcoin had plainly become a mania. Other cryptocurrencies were proliferating, it was on the news all the time, and otherwise sensible friends would ask me whether they should buy some. Google Trends shows an immense spike in interest that year. Nothing like that is afoot now:  U.S. interest is greatest in the state of Nevada; and global interest is greatest in Nigeria. Make of these things what you will. What is going on? Bitcoin can be regarded as a "gold on steroids" trade, for those who believe that the global order is about to break down, taking fiat currencies with it. Yet bitcoin is far outpacing gold. The following chart from Chris Watling of Longview Economics maps the two assets against each over the last two years, and reveals bitcoin (if you squint) as a kind of hyperactive version of gold. It suggests that the recent rally may be providing a signal to buy gold, which has been off the boil for a couple of months. But it also suggests that if there is a sense of horror afoot, it is showing itself only in bitcoin:  Bitcoin is also outperforming other cryptocurrencies. And while the dollar is weak at present, it is performing much better than other hedges against monetary debasement. It is one of the first rules of journalism never to be embarrassed to admit ignorance. I can't explain why this is happening. Errors & Omissions The Financial Analysts Journal A few weeks ago, I published this piece on the 75th anniversary edition of the Financial Analysts Journal, which was graced with a major study of the performance of university endowments over the past century by Cambridge University academics Elroy Dimson, David Chambers and Charikleia Kaffe. The CFA Institute, which publishes the journal, has written to point out that the facsimile cover I featured was the first edition of the Journal of Finance. The one they meant to provide was this one, published in January 1945 and then called just the Analysts Journal:  They were kind enough to send me a facsimile of the entire journal. The name that leaps out from the front page is, of course, Benjamin Graham. Fascinatingly, his piece is about a debate over whether to establish a qualification or credential for security analysts. At that point the idea was to call it the QSA (Qualified Security Analyst), but over time that designation became the CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst). It was a contentious idea at the time. Here is Graham's conclusion:   The arguments against included that none of the regulators were making the slightest demand for such a qualification, and nobody working in the business seemed to be clamoring for it either. Starting the exam would be expensive, and would inevitably hinge on mastering knowledge, rather than necessarily showing the softer quality of "judgment" that is often needed when pricing securities. The rest is history. The profession has grown rather a lot since then, buttressed by CFA designations, and also MBAs, and has gone global. For detractors, this has encouraged over-confidence and groupthink, as for example when everyone trusted their value-at-risk models until the last seconds in 2008. On the more positive side, the CFA designation has forced the people who look after other people's money to undergo rigorous training grounded in ethics. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland On Monday, in an exasperated commentary on the British government's attempt to play a game of chicken with the EU and convince their interlocutors that they were prepared to risk trading with the bloc on the same limited terms that Australia does, I said this: The EU is 17 miles away from the U.K. and can be reached by train. Australia is on the other side of the planet. On the face of it, the notion that the U.K. will trade on the same terms with both is horrifying. I was right that Boris Johnson would soon cave, and indeed the talks are back on. But I was wrong to say that the European Union is 17 miles away from the U.K. The EU in fact shares a land border with the U.K., in Ireland. One of the signal errors of the British establishment over the last five years of the miserable Brexit process has been to assume that Ireland isn't really there. The issue of the Northern Irish border was never turned into a big issue during the referendum campaign, and the Brexiteers who took over the country seem never to have questioned the notion that a compromise could be found. Taking Ireland for granted is a common British failing, and in this case it cost Britain dearly. Unwittingly, I just demonstrated that tendency. Sorry. Georgia Going through the possibilities for a long drawn-out process before we find out whether a Blue Wave has really hit America, I forgot to point out one crucial detail. Under Georgia's laws, elections for both its Senate seats could move to a special run-off on Jan. 5 if nobody gets an overall majority. This is likely in the seat currently held by Republican Kelly Loeffler (appointed by the governor to replace retiring Senator Johnny Isakson until the election) and may happen in the other. This means we may not know who controls the Senate until next year. This chart, from Dan Clifton of Strategas, shows the Georgia election is wide open:  On balance, an inconclusive result is unlikely. Four years ago, for the first time ever, every state that elected a Senator chose one from the same party as their favored presidential candidate. Generally, Republican candidates tended to be slightly more popular than Donald Trump. The same thing is happening again, with the race largely seen as a referendum on Trump. In state after state, Democratic candidates are polling slightly behind the numbers shown by Joe Biden. The only significant exception is Arizona:  A rising tide for Biden should, therefore, raise all Democratic boats, and vice versa. Whoever wins the presidency is likely to have the Senate on their side. But the bottom line is that every seat will make a difference, so the Georgia elections could keep us all in suspense. Survival Tips Good news. There are no more presidential debates to suffer through in the U.S. I sat through it, both candidates behaved themselves (more or less), and neither said anything that would surprise anyone who'd been paying attention already. The cable networks' polls suggest it was a tie. Nothing about trading in the dollar or S&P futures suggested anyone in the markets thought anything out of the ordinary had happened. So, I don't need to write any more about it. And now there are less than two weeks to go, everyone. To ease the stress over the next two weeks, and for a reminder that it is possible to play in harmony, try listening to this. It's a piano duet by Schubert and it's very soothing. Have a good weekend, everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment