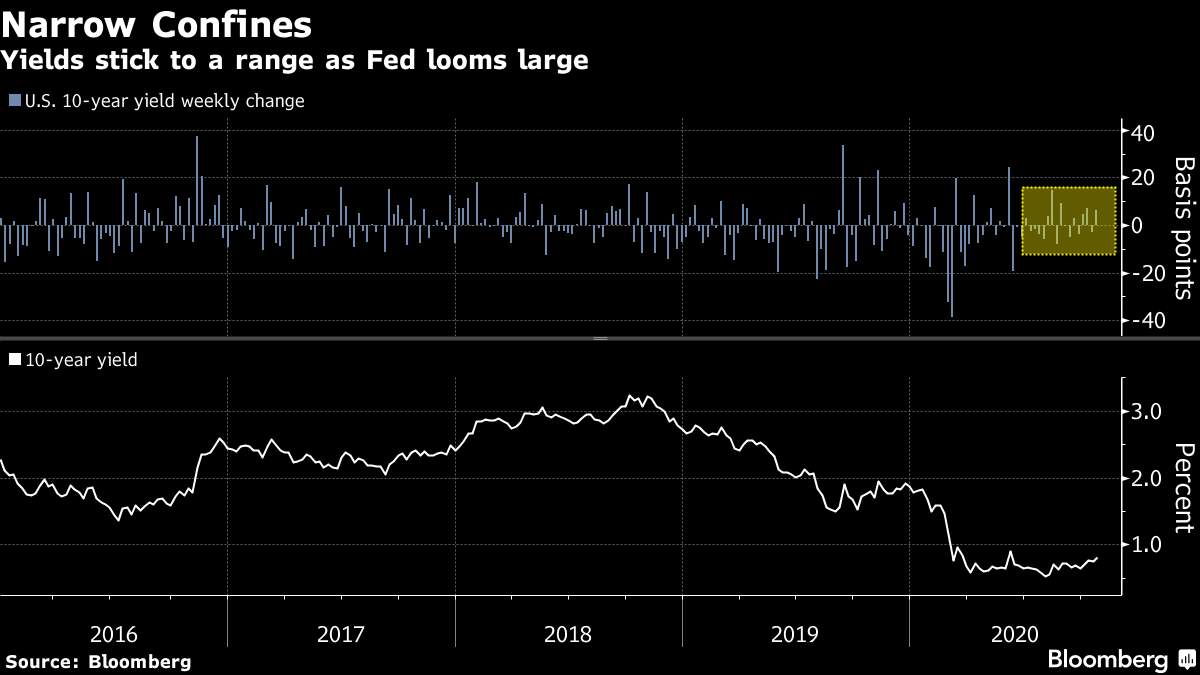

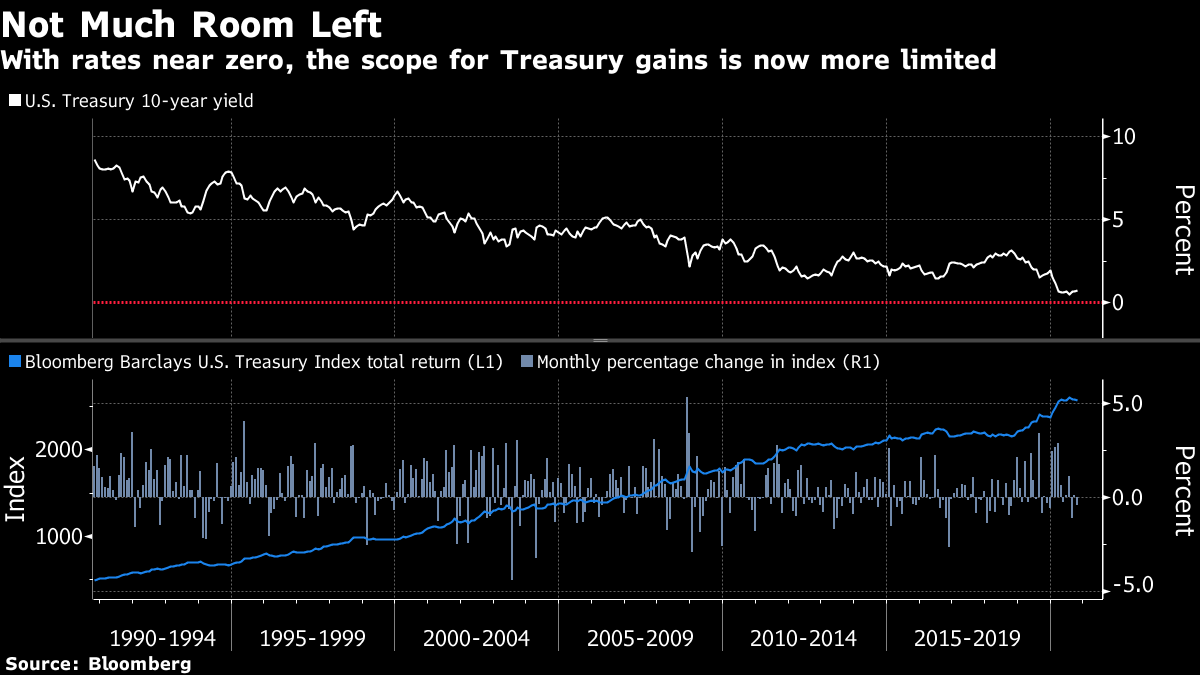

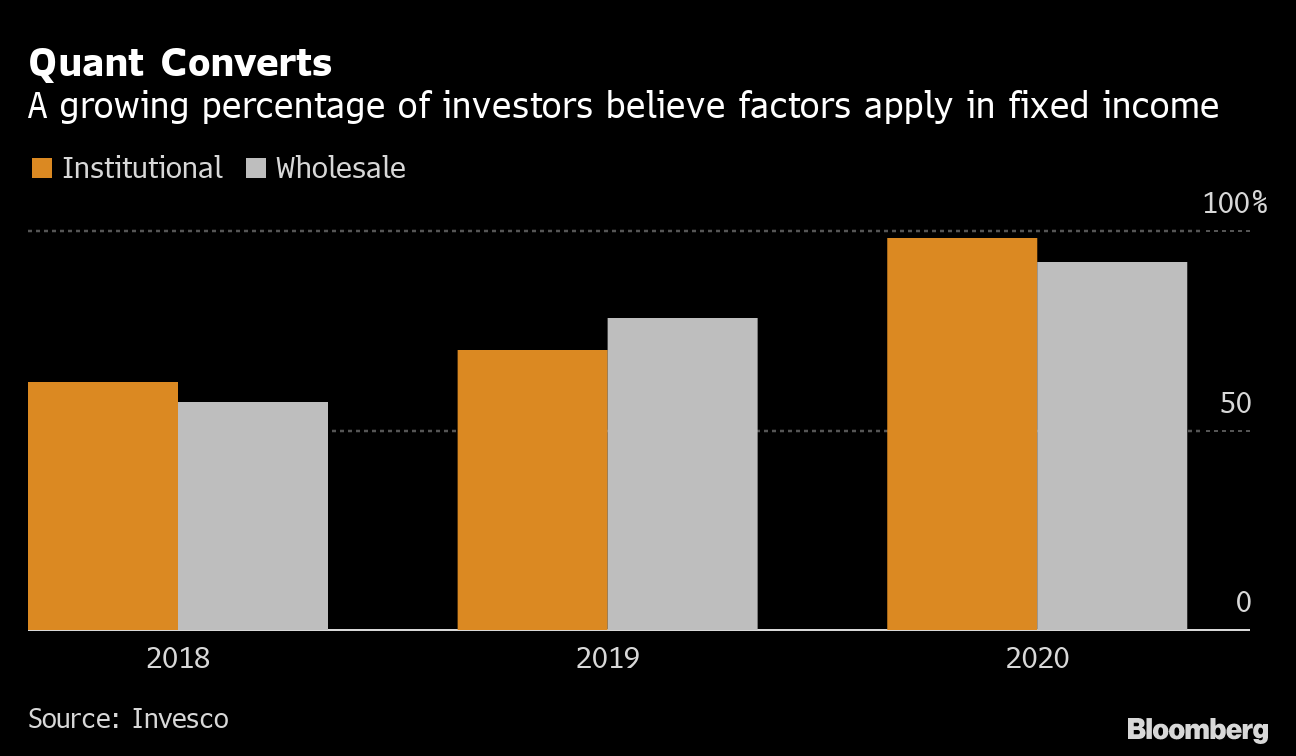

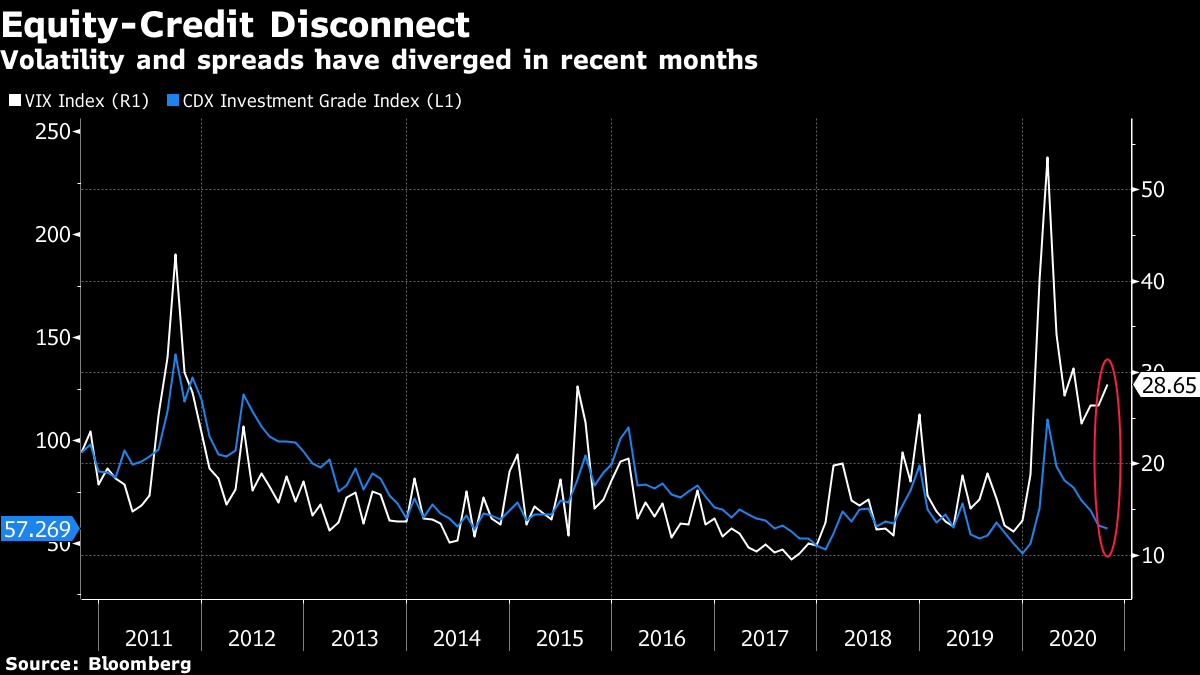

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's been trained not to push long-end yields up too high. I'm cross-asset reporter Katherine Greifeld, filling in for Emily Barrett. Stealth Yield-Curve ControlFederal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans threw cold water on a popular bond market narrative this week. The consensus over the past several months has been that should long-dated yields rise meaningfully, the central bank stands ready to bulldoze rates lower by shifting their purchases further out the curve. But with rates so low, that might not be as potent as in the past, Evans said. "I don't think there's a lot of scope for portfolio-balance effect to really lower long-term interest rates a lot because they're already very low," said Evans in a conference call with reporters. "So, we could try to do more on asset purchases, but I'm not quite sure how far we would get." That comment likely came as a surprise to the scores of bond traders who have been all but trained not to push yields too high. Policy makers have repeatedly demurred on the topic of yield-curve control: In June, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said they were still in the "early stages" of evaluating it. Later that month, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard said he didn't see it as a pending policy. In August, Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida said yield caps could be a possibility in the future.  As the will-they, won't-they continues, the mere prospect of 'they might!' has effectively capped yields to the upside as investors faithfully rush to buy any dip. That's confined 10-year Treasury yields to a tight range. That Pavlovian response has been tested this week, with U.S. negotiators seemingly nearing an agreement on a further coronavirus fiscal relief package (though such a deal has been teased even more than yield-curve control). Bubbling optimism about a re-energized U.S. economic recovery and the inflation that might accompany it sparked a sell-off in long bonds, pushing the 5-year, 30-year yield curve to its steepest level since December 2016.  But as benchmark rates breached 0.85% on Thursday, options market activity suggests that bond traders are drawing a line in the sand at 1%. And given how mightily ultra-low rates have helped interest rate-sensitive sectors of the economy bounce back, a material rise above that level could push the Fed to explicitly announce yield targets, according to Yardeni Research. "There is a possibility that if the stimulus package finally gets through, the perception will be that the economy is doing reasonably well and now it's going to be on fire," chief investment strategist Ed Yardeni said. "If the bond yield starts moving above 1%, then I think the Fed is going to be very concerned because housing has gotten a tremendous lift here from low mortgage rates." The 60/40 Portfolio is Dead. Right?The Fed's path forward is key to another debate bubbling in financial markets: is the classic 60% stocks, 40% fixed-income strategy dead? The argument goes like this: with Treasury yields near all-time lows, bonds are no longer able to buffer stock market downturns like they have in the past. That portfolio mix has returned about 9% so far this year -- roughly in line with annual returns of nearly 10% since the 1980s -- but with Treasury and equity valuations so stretched, such gains could be hard to come by again.  That's fueled a hunt for new hedges to accompany or replace the role that U.S. government debt has played for decades. JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s John Normand suggests holding the yen or gold, though both have proved less reliable than Treasuries historically. Swan Global Investments is trying out equity options as an alternative. Meanwhile, Eaton Vance Corp. and Invesco Ltd. recommend giving the Chinese government bond market a shot, where 10-year securities still yield above 3%. Columbia Threadneedle's Ed Al-Hussainy says this all misses the point, as it is the inverse correlation that Treasuries have to risk assets, rather than their return potential alone, that makes them a valuable hedge. "What's important is what role are Treasuries playing in my portfolio," said Al-Hussainy, a senior analyst for global rates at the asset manager. "Treasuries are an exceptionally good buffer of risk, whether it's equity or credit. Chinese debt, not really. If U.S. equities go down, a Chinese bond isn't going to help me from that perspective."  Sure enough, the correlation between 10-year Chinese bonds and the S&P 500 is a paltry 0.03 on a 40-day basis. Swap in benchmark U.S. debt, and the link strengthens to about 0.24. And anyway, low starting yields don't necessarily put a lid on gains, said Al-Hussainy. Look no further than Europe for proof: A European version of the 60/40 portfolio returned roughly 4% from the start of 2020 through mid-October, according to numbers crunched by Bloomberg's Cameron Crise. And that's even with a relatively anemic equity market and deeply negative yields. Quants Are Excited About BondsWhile quantitative equity traders grapple with existential doubts, the bond market is brimming with optimism. Almost every respondent in Invesco's 2020 survey of institutional and wholesale investors answered that they think factor investing can be applied to fixed-income. The tally of believers among investors with more than $25 trillion under management totaled 95%, a jump from 74% last year and just 59% in 2018. The enthusiasm is another byproduct of the zero-rate world that's pushing investors outside of their traditional Treasury hedges. A systematic approach -- which selects securities by based on parameters such as how inexpensive or profitable they are -- has added to the urgency for quant strategies in the space, according to Invesco's Georg Elsaesser.  "Coming from a 30-year bull market in fixed income, statistically speaking, whatever you bought it would have got you a decent return," Elsaesser, a portfolio manager at Invesco, told Bloomberg News this week. "That's changed now. Interest rates can barely go lower, so there's a much more pressing need for alternative return sources." 40% of those polled said that they're already employing fixed-income factors as the pool of negative-yielding debt again approaches all-time highs. Another 35% of respondents said they are considering it. Election Credit StormSomehow there's only a week and a half until the U.S. presidential election, but you wouldn't know it from looking at credit markets. While the Cboe Volatility Index -- the equity market's "fear gauge" -- hovers around a still-elevated reading of 30, corporate bond spreads have been steadily grinding back to pre-pandemic levels. That's opened up a rift between the VIX and investment-grade spreads, which tend to loosely track each other. That divergence is an opportunity in the eyes of Saba Capital Management founder Boaz Weinstein, whose flagship fund has surged 80% in 2020 through September. The current status quo can't hold for much longer as the U.S. election approaches and coronavirus cases tick up, he said. "It's like a calm before the storm," he said in a Bloomberg Television interview. "Equity volatility is almost inescapably high. Is that a good form of insurance? The payoff profiles are nothing like they were back in January. Whereas in credit, we're almost back to where we were in January."  To take advantage, Weinstein shorting credits that he views as vulnerable -- he declined to say which -- while adding bullish exposure to issuers such as International Business Machines Corp., AT&T Inc. and Walt Disney Co., which he says are "going to be in good shape" regardless of how things shake out. However, Financial Enhancement Group's Andrew Thrasher has a different interpretation. While the two measures have drifted apart, there's no guarantee that spreads will widen to meet the VIX, he said on Twitter. Rather, such dislocations tend to result in lower equity volatility, with spreads being "right." It's fair to say that credit investors don't share Weinstein's concern. Risk premiums on BBB-rated debt -- the last rung before junk -- shrunk to the tightest level since early March last week as dwindling supply met robust demand. And with the Fed's corporate bond backstop still firmly in place, any credit storm may be closer to a drizzle than a hurricane. |

Post a Comment