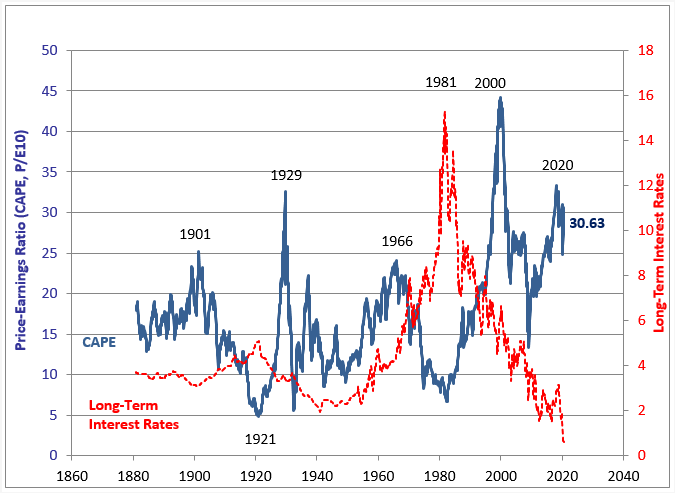

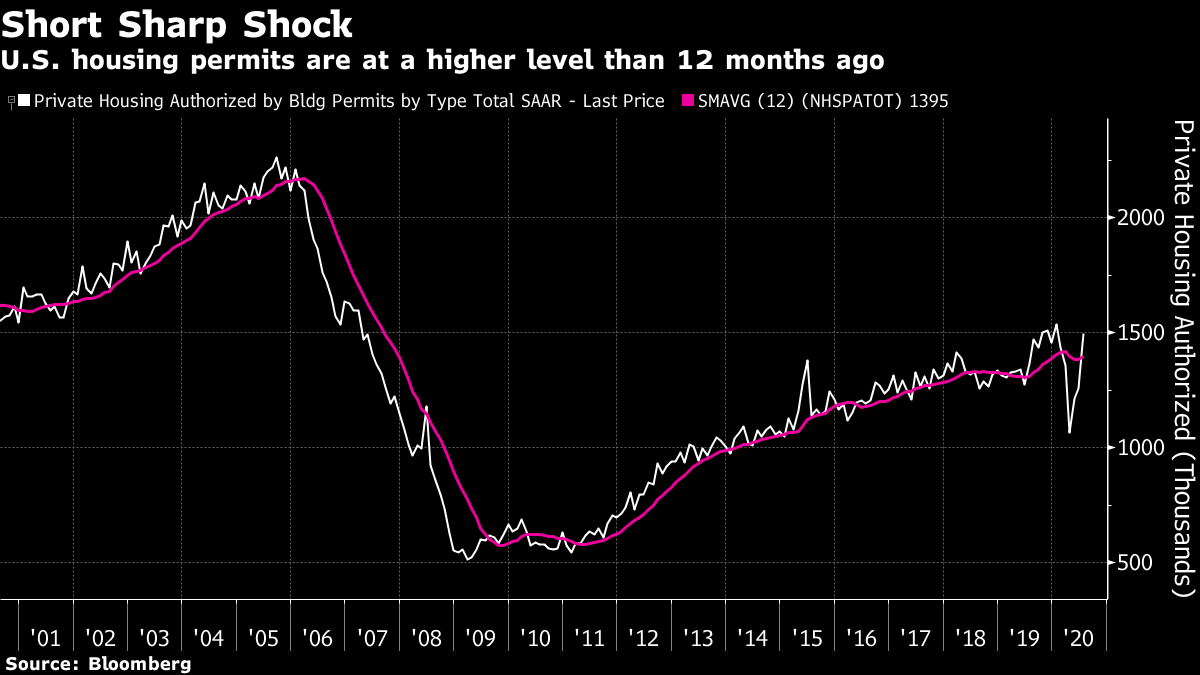

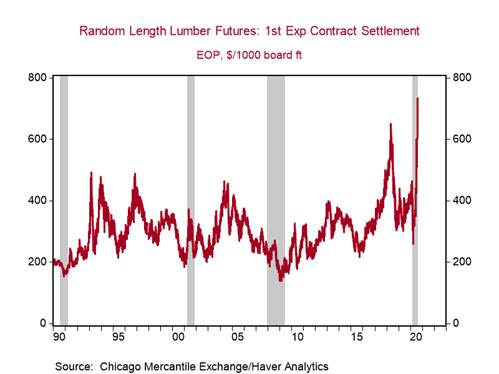

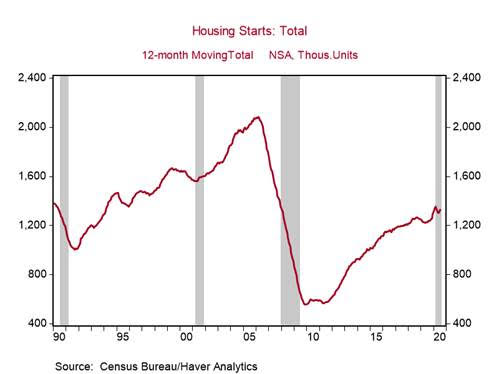

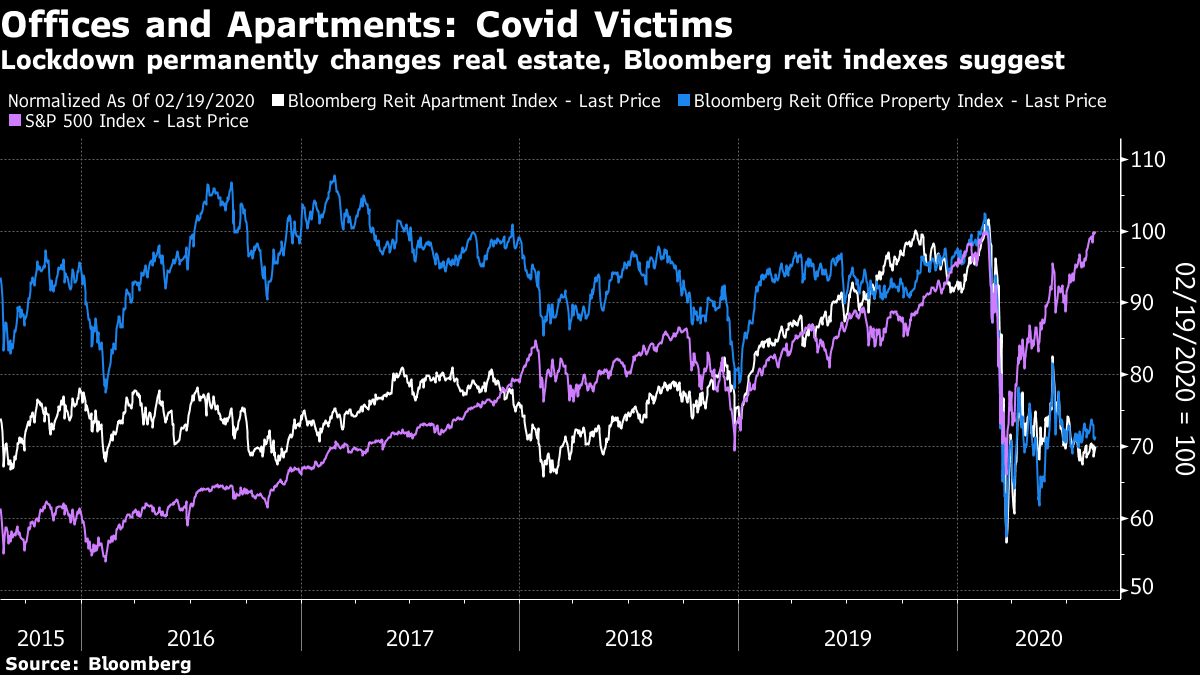

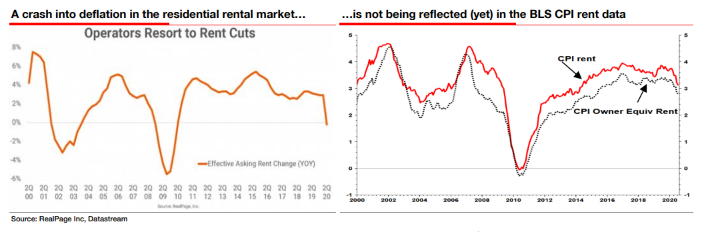

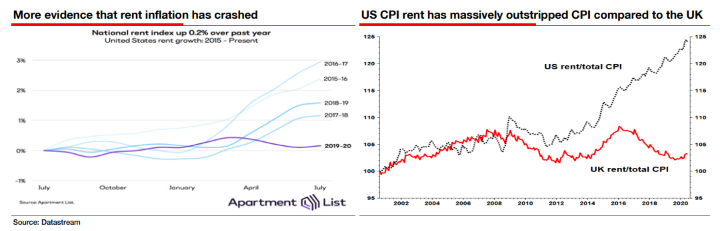

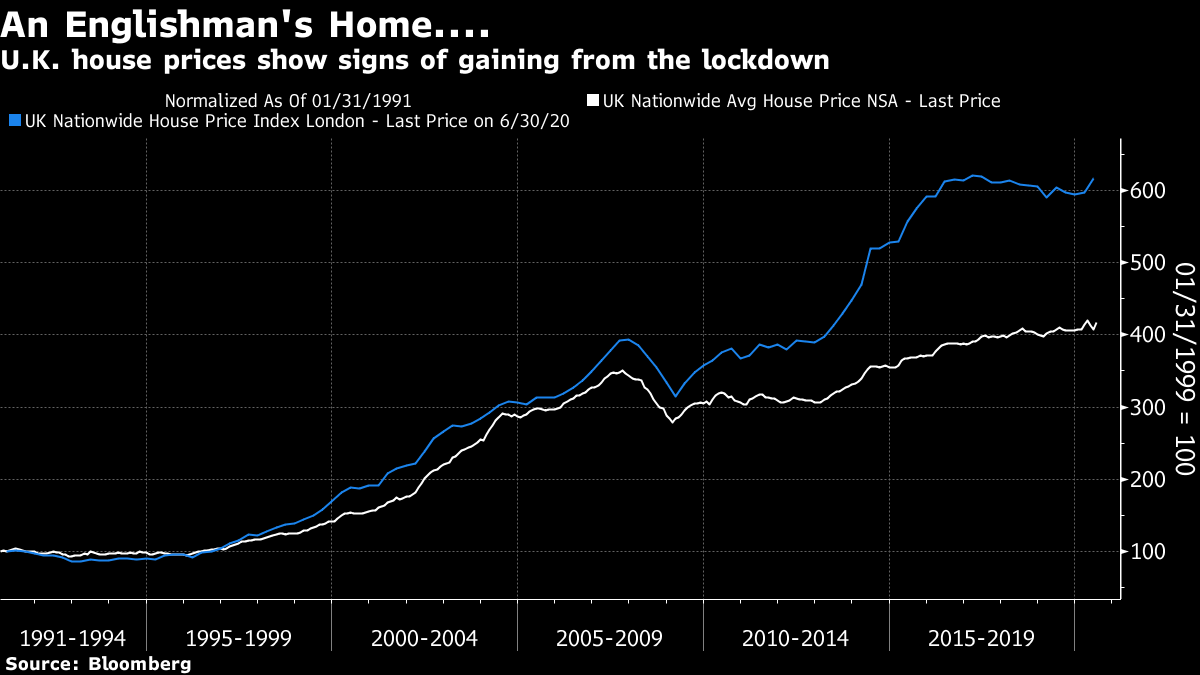

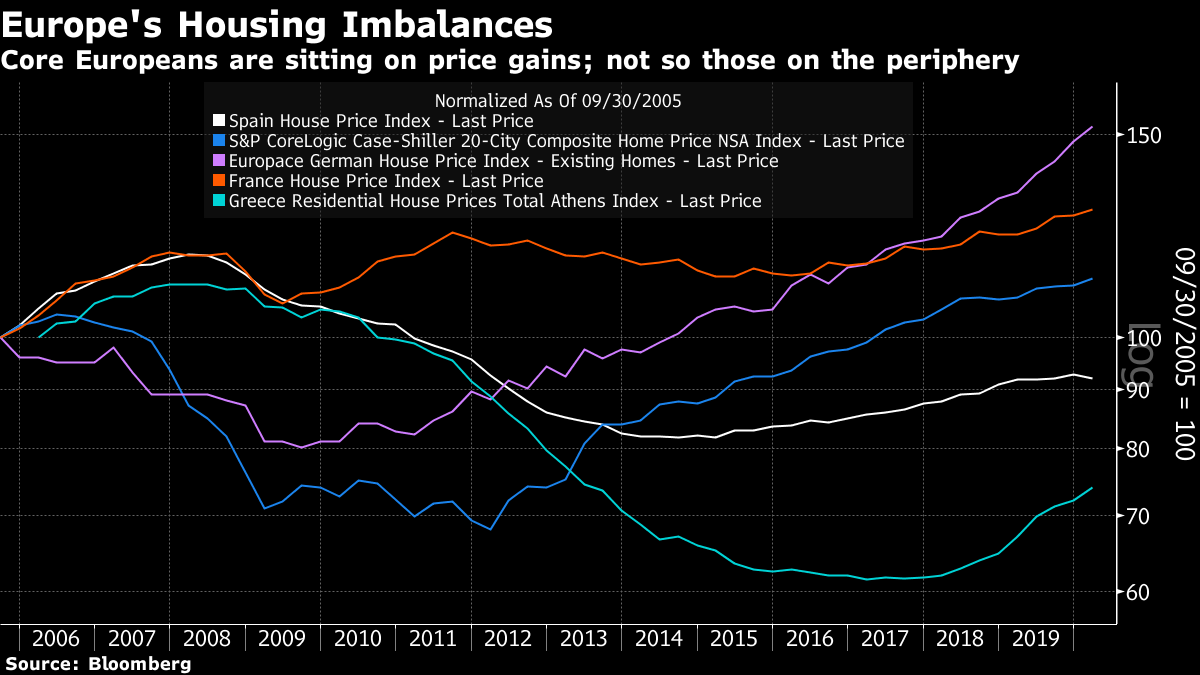

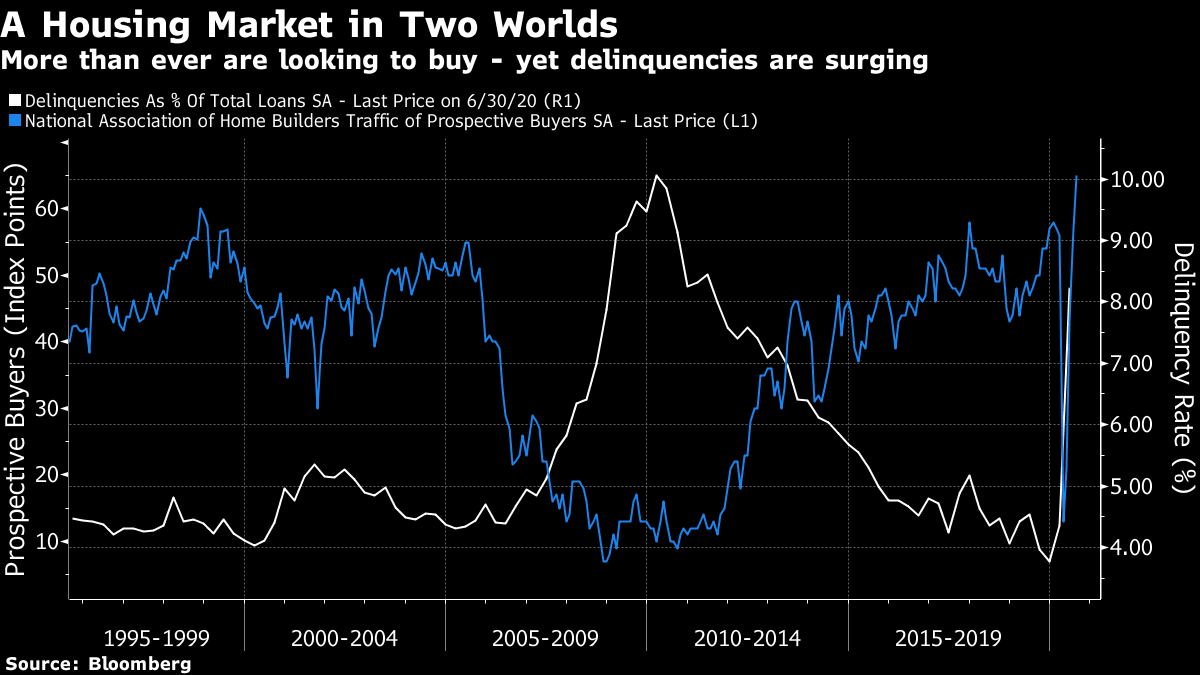

Six Months That Shook The World It took exactly six months. The S&P 500 closed at a record high Feb. 19, and set a new one Aug. 18. I didn't see it coming, and think the market is way too expensive now, which is another way of saying I have been wrong. I started yesterday's newsletter by asking "What'd I miss?" Evidently, the biggest thing I missed was that the world's most followed measure of the stock market could possibly make a full recovery so quickly. There are justifications for the current level of U.S. stocks. There are also reasons why they have reached this level so quickly. The two aren't necessarily the same. For now, confronted with the clear evidence that I've been wrong, I won't focus on how stocks could have done this, even with the remarkably committed help of the Fed. Instead, let me try to offer a swift radiography of what has just happened. First, and I thank Canaccord Genuity for pointing this out, this recovery is startlingly similar to the one after the global financial crisis, even though the falls that preceded them were very different. If we keep following the same path, there is some more upside ahead:  Meanwhile, this has in many ways been a bifurcated recovery or, to use the phrase of Financial Insyghts' Peter Atwater, a "K-shaped recovery," in which two lines on a chart diverge. So far, this has been a far better recovery for the mega-caps of the Russell Top 50 than for the smaller companies of the Russell 2000:  Winners and losers are still, at this stage, dominated by those companies that have done badly out of the pandemic, and those few that have done well. At this level, there is no sense of the market "looking through" the pandemic and its associated shutdown to discount future events. Instead, internet retailers are up 40% in round numbers since the previous top, and hotels, resorts and cruise lines are down by the same percentage:  While this is a victory for the bulls who called on us to start buying at the bottom, it continues to be an even bigger victory for contrarians who entered the crisis holding gold and long bonds, or those who had the guts to see that the FANG stocks were now regarded as defensive plays. While the S&P 500 has gone nowhere for six months, each of those asset classes has done very nicely. The S&P is slightly ahead of the rest of the developed world, but it owes this entirely to the FANGs:  Does any of this make sense? Earnings and sales have fallen over the last six months, and it is hard to see why anyone's predictions for them in the future would have improved. So long-term stock valuations look more stretched than they did before. What follows comes from the website of Yale University's Nobel laureate economist Robert Shiller, and shows his cyclically adjusted price/earnings, or CAPE, ratio for the S&P 500, and long-term interest rates, going back 140 years:  This chart was calculated at the close on Aug. 11. The rise in stocks since then has taken the CAPE to 31.14. It peaked before the Great Crash of 1929 at 32.56. It has only previously been higher at the top of the internet bubble, and for a month or two in 2018. But long-term interest rates, by Shiller's method of calculation, have never been as low. All else equal, lower rates justify higher multiples. A lot is riding on those low rates. Arguably the most profound market and economic changes wrought by the pandemic so far can be seen in the robust state of the housing market. In the U.S. and around the world, this can be viewed two ways. First, it is unambiguously a sign that strong economic growth is in the pipeline. Secondly, it suggests that all the nastiest fissures and polarizations in society that we have bemoaned since the last crisis are set to deepen far more. The latest news is that U.S. housing permits surged last month. Using a 12-month moving average, we can see that the sharp fall has already been corrected, and new housing is being started at a considerably greater rate than it was a year ago:  This is straightforwardly good news for employment, and for a range of producers of the materials that go into building a house, and making it ready for habitation. As Mickey Levy of Berenberg Capital Markets LLC illustrates in this chart, lumber futures are through the roof:  Nothing like this has been seen before during a recession. Similarly, things have seldom been better for sellers of building materials. To use the Keynesian phrase, the economic benefits of the housing boom are multiplying nicely:  Further, there is good reason to believe that this upturn is more sustainable than the last one, which of course blew up into the financial crisis of 2007-08. As Levy also points out from data on housing starts, that crisis started after years of overbuilding created a glut of supply. Now, with the number of people ready to start their own household growing again, builders are playing catch-up:  This has some very positive market effects. According to the National Association of Home Builders in the U.S., the market has never looked stronger. Meanwhile, the performance of home-building stocks relative to the rest of the market is at a post-crisis high:  Now, however, we come to the most disquieting aspects of housing's performance. Demand is driven in part by the shift in what people are looking for in a home. If your home is to be your place of work, and also the place where your children are to be educated, and you don't have the chance to go to large gatherings like sports events or concerts, then the arguments against city-dwelling in an apartment become overpowering (he typed, in his Manhattan shoe-box), while the appeal of a house outside the city grows much greater. This is fueling interest in buying new houses. It will also entail selling apartments, and should therefore mean that both buying prices and rents for apartments will fall. And of course, office rents can be expected to fall. Indeed, Bloomberg's indexes of U.S. real estate investment trusts holding apartment buildings and office developments have juddered downward in the last six months:  It has broader implications, as pointed out by Albert Edwards, the famously bearish chief investment strategist at Societe Generale SA. He points to clear evidence that rents are already being cut, which hasn't yet shown up in inflation data. As I detailed yesterday, core inflation rose sharply last month. The likely exodus from rental accommodation is at least one reason to brace for renewed deflationary pressure:  This is important, because rents have increased significantly in the U.S. over the last few years, as younger families have flocked to living in cities once more. There has been no such trend in the U.K., as he points out. If the signs pointing toward a major exodus from city-living are confirmed, there is every reason to expect a lot of displacement as a result. For now, building outside cities is a stimulus for the economy, but in the longer run this will be counterbalanced by casualties elsewhere.  This leads to another concerning issue. Housing is central to social inequality. It has ramifications that go beyond national boundaries. Another ratchet upward in housing prices could exclude yet more people from the benefits of capitalism. That could be very unhealthy. For one simple example, look at house prices in London and in the U.K. as a whole over the last 30 years, as recorded by the Nationwide Building Society. Britons build their personal finances around their houses, but the rise in prices in the last 20 years has had the effect of excluding a new generation from the option of owning. This creates dangerous tensions. Added to this, the government in 2013, under the premiership of David Cameron, opted to juice the housing market. That led to a huge increase in London house prices, which wasn't mirrored elsewhere in the country. It was exacerbated by an influx of European buyers, who were worried about the risk of a collapse in the euro, and saw the possibility of safety in London. The huge gap that opened up between house prices in London and the rest of the country by 2016 was both a cause and a symptom of the populist anger that led the U.K. to vote to leave the European Union that year. That vote, not at all coincidentally, stopped the rise in London prices. If large numbers of Londoners now decide to take their profits and buy houses in the countryside, the social effects will be interesting to behold:  Moving to the euro zone, the crisis that hit a decade ago was largely driven by financial imbalances. Low interest rates appropriate for Germany but inappropriate for the then much healthier economies of the periphery led to an influx of money into property in countries led by Spain. This chart shows house prices in Spain, which carried on growing even after the U.S. had peaked, compared to the U.S., Germany and France. All are normalized to start in the final quarter of 2005, ahead of the crisis. I also committed chart crime by including an index of Athenian house prices which started two quarters later. It gives useful context. As can be seen, Spanish prices blew up and collapsed, bringing dreadful banking problems in their wake. Greek housing prices went through the floor. And yet French and particularly German house prices have performed very well since the continent began to get over its crisis. German house prices, remarkably, have roughly doubled — a natural outcome of interest rates that have been zero or negative for years. This pattern doesn't lend itself to European unity or cohesion. Another big upward shift in house prices as a result of the pandemic will only deepen the divisions:  Then we have the bizarre situation in the U.S. The following chart shows the National Association of Home Builders' measure of traffic of prospective home buyers, which is at an all-time high (it is a diffusion index set so that any number above 50 shows growth). Meanwhile, the Mortgage Bankers' Association's quarterly measure of delinquency rates has just shown a record increase in those behind on their loans. Those who have money are looking to buy, aided by record low mortgage rates. Those who have lost their jobs are behind on their mortgages and may be forced to sell:  Economic and social inequality was already a pressing issue for the U.S. six months ago. What is happening in the housing market, where people living in two different economic worlds collide, can only make those issues much worse. Survival Tips It's often said that you shouldn't let the perfect be the enemy of the good. This is usually very true. Particularly when facing a deadline, do something good and don't worry about perfection, which is unattainable anyway. But there is something to be said for aiming for perfection despite this. I spent a large chunk of my career writing columns of no more than 300 words. You can come quite satisfyingly close to perfection if you only have to write that much; have one decent idea, come up with two or three decent points to back it up, and then write it succinctly, and you have something on which it is very hard to improve. Perfection might be overstating it, but there is great satisfaction to be had in doing something on a small scale really well. That was the animating philosophy of a friend who spent much of his time writing three-minute pop songs. As with a 300-word column, you can get close to perfection if you only need to hold people's attention for three minutes. To quote two examples, both prompted by citing a piece by Schubert yesterday, try listening to Massive Attack's Unfinished Sympathy, or the extraordinarily intense Der Doppelganger from the last song cycle that Schubert himself wrote, called Swan Songs. The great Hungarian pianist Andras Schiff once said that there is more drama in the concentrated four minutes of Der Doppelganger than in the entire works of Wagner, and I'm inclined to agree. Both songs, in very different ways, are pretty much perfect. Maybe we should aim for perfection a little more. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment