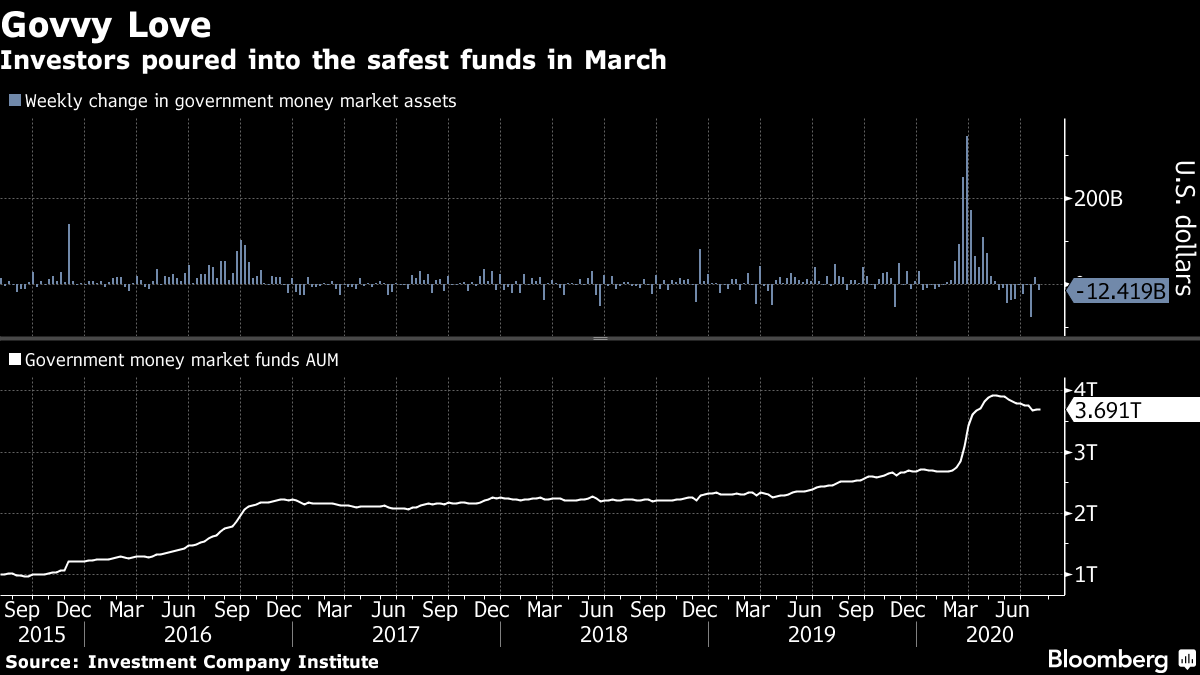

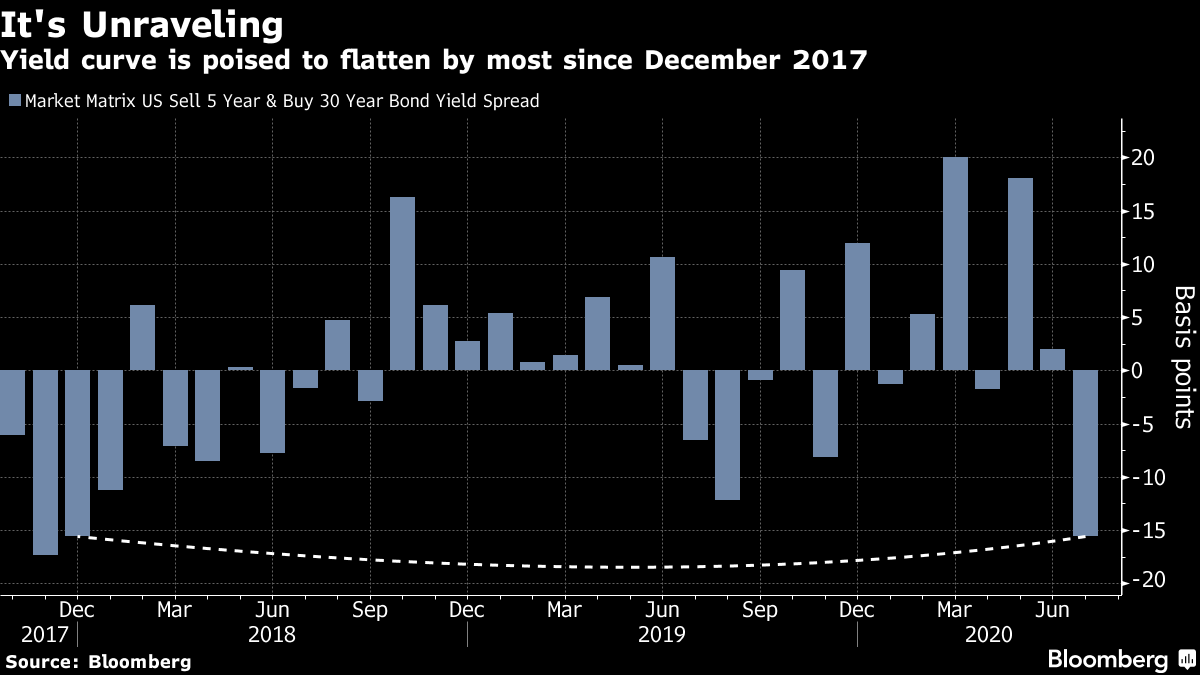

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's hoping for the best, prepared for the worst, and unsurprised by anything in between — channeling Maya Angelou. A Word on Inflation One takeaway from this week's understated Fed meeting is that, in these trying times, the market has faith in Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. There wasn't much to react to in Powell's comments wrapping up the July policy meeting Wednesday, but some subtle moves in rates on the day suggest traders were putting money on the central bank's ability to meet its mandate. Specifically, breakeven rates -- the inflation compensation embedded in Treasury securities -- climbed to levels last seen in late February, before all hell broke loose.  To be clear, this chart isn't showing a stunning recovery. Clambering out of a hole in March has taken nothing less than shock and awe from the Fed, it reflects expectations over the next decade, and it still implies consumer price inflation will undershoot the Fed's 2% goal by almost a half-percentage-point. If you convert to the Fed's preferred inflation gauge of personal consumption expenditure, it's a roughly 0.8 percentage point shortfall. Still, it's progress, and the recent trend has been sufficient to lure plenty of big-time investors into cheap hedges against a sharper-than-expected rebound. And the rising trend may have legs if the Fed manages a convincing overhaul of its inflation-targeting strategy, which is expected as soon as September. The Fed has been engaged in a soul-searching exercise since November 2018. Fed watchers expect officials to strengthen guidance about the path of interest rates by linking the timing of any rate increase to thresholds for unemployment and inflation that would imply a greater willingness to run the economy hotter.  Real Negative And yet that strong-growth scenario seems a long way off. Treasury real yields -- the rate on government bonds if you strip out inflation -- have been dropping precipitously. The 10-year is around a record low of -1%. That's been accompanied by a sustained slide in the dollar, and all-time highs in gold. This is in large part a function of the market's conviction that interest rates aren't lifting off the zero bound for many years to come, as this chart of overnight index swaps -- a proxy for the Fed's risk-free rate -- for the next five years illustrates.  And as if that wasn't enough, Jan Hatzius at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. doesn't see the Fed hiking rates again until at least 2025. And the point wasn't lost on BlackRock CIO Rick Rieder, who offered an extended aviation metaphor in a thread Wednesday to make his point that: "The #Fed likely has an impressively long runway yet, as it could be a very long time before we regain full #employment, which didn't even appear to be #inflation-accelerating at a 3.5% #unemployment rate." Indeed, Fed policy could well get easier before central bankers start even thinking about thinking about raising interest rates (Powell reiterated Wednesday that he's not). The latest data on U.S. gross domestic product showed the world's largest economy shrank at an annualized rate of 32.9% in the second quarter -- the fastest contraction on record. In Wednesday's press conference, the chairman described this downturn as "the most severe in our lifetime," and the Fed's current stance as "hope for the best and plan for the worst" -- proving yet again that he's as adept at pithy lines as his way-way back predecessor Alan Greenspan was at sidestepping them. That's further reassurance for the market that the Fed has laid the groundwork for more-aggressive intervention as needed in the months ahead. The central bank announced Tuesday that it's extending to year-end the emergency lending facilities that were supposed to expire by October. That applies to the primary dealer and money market facilities, as well as the Fed's newer experiments with corporate-bond buying, paycheck protection and Main Street lending programs. One move that still seems beyond the Fed's contingency plan, notably, is a further cut in interest rates. Powell offered no change in his previously stated views. Hope apparently springs eternal in fed funds markets, though, where traders still nurture positions that would benefit from a negative policy rate in year from now. Get Out One effect of negative real yields that serves the Fed's purpose, as Ben Emons at Medley Global Advisors puts it, is "to incentivize people to get out of cash." So it's worth considering the massive implications of that migration, given the cash hoards that have built up all around global markets since the March cataclysm. The stampede of global investors into cash-like products drove yields on the shortest-term Treasuries below zero. Government money-market funds that invest in this 'super-safe' stuff were deluged, and months later their tally of assets under management isn't far off those all-time highs that approached $4 trillion.  The much lower longer-term average suggests huge amounts may be destined for riskier climes as market confidence returns. And this week we have a case in point, as Bloomberg reporters Masaki Kondo, Chikafumi Hodo and Daisuke Sakai crunched the numbers on the world's biggest pension manager, with $1.4 trillion in assets. Japan's Government Pension Investment Fund boosted its Treasuries holdings to almost half of its foreign bond portfolio in the year through March 31, with almost 40% of that amount in maturities of three years or less. That's a big chunk of short-dated securities for an institution that has to match long-term liabilities. The GPIF's next investor update for the quarter through June will show how it's shifted those allocations since -- though surging flows to corporate credit funds as sovereign yields have plunged globally offer a strong hint. And the lower hedging costs associated with a slumping dollar have only added to the shine on U.S. corporate bonds. Longevity But risk appetite hasn't returned in sufficient force to drown out the clamor for long-dated government debt. Thursday's grim U.S. GDP numbers -- despite their backward-looking nature -- reignited haven trades that saw the 10-year benchmark yield dip briefly below the 0.54%-0.78% channel it's plied since early March. As our rates reporter Ed Bolingbroke points out, the last time that threshold was in sight, following a stellar auction of 30-year Treasury bonds on July 9, Citigroup strategists warned that a close below it could trigger convexity-hedging, which would accelerate the decline in yields.  As it happens, governments around the world are more than aware of the opportunity this surge in global demand presents for them to lock in historically low rates on long-term borrowing. Australia took advantage of its exalted status as one of the dwindling ranks of developed markets with positive yielding debt, to sell a new 30-year bond this week. That was its longest-dated issue yet for a 1.22% rate, and it cemented Oz's status as the 'Rolls Royce' of global sovereign bond issuers, according to AFR . And Indonesia drew record demand for its 2048 bond. The U.S. is no exception. It's looking to skew borrowing to the longer end of the curve in the second half of this year to help fund a deficit that's already hit $2.7 trillion in the first nine months of this fiscal year, and another large stimulus package that's still on the blocks in Congress. Next Wednesday the Treasury releases its plans for how it will spread out that fundraising effort. It's expected to move away from the astronomical bill issuance in April-June, when it borrowed close to $3 trillion in short-term debt -- more than the total bond markets outstanding for most countries, excepting Japan and China, says Goldman Sachs rates strategist Praveen Korapaty. Wall Street's anticipating fresh records in auction sizes for notes and bonds, particularly the 10-, 20, and 30-year maturities. Don't expect that to make much of a dent in the market, Korapaty warns, as investors are more likely to be surprised by steady numbers than by bigger ones. That's not great news for the curve steepener trade, which had flourished in the months after March on the conviction that the Fed would pin short-end rates, while massive supply and a gradual recovery would buoy the longer end.  A bleaker outlook on the recovery as Covid-19 cases rebounded, and a strengthening view that the central bank might boost asset purchases of longer-maturity debt, has been driving the curve flatter for the past six weeks. The gap between the five- and 30-year yields is on track for the sharpest compression since December 2017. Societe Generale's Subadra Rajappa reckons don't fight it: not in August, when seasonal effects are in favor of lower rates and a flatter curve, even without a global pandemic on the loose. Bonus Points In a zero-rate world, the trade-off between a return on your money and a return of your money is way trickier. I'd rather be alone.. hunting clues to alien life among Mars' long-dead microbes. The U.S. 2020 election will go on. Many American public-health specialists are at risk of burning out as the coronavirus surges back. Kodak is relevant again. Laundry chic. |

Post a Comment