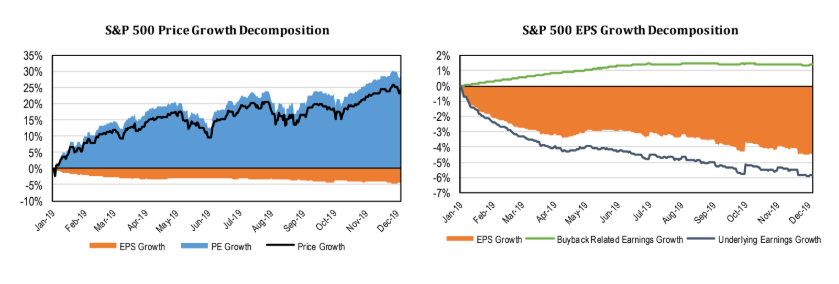

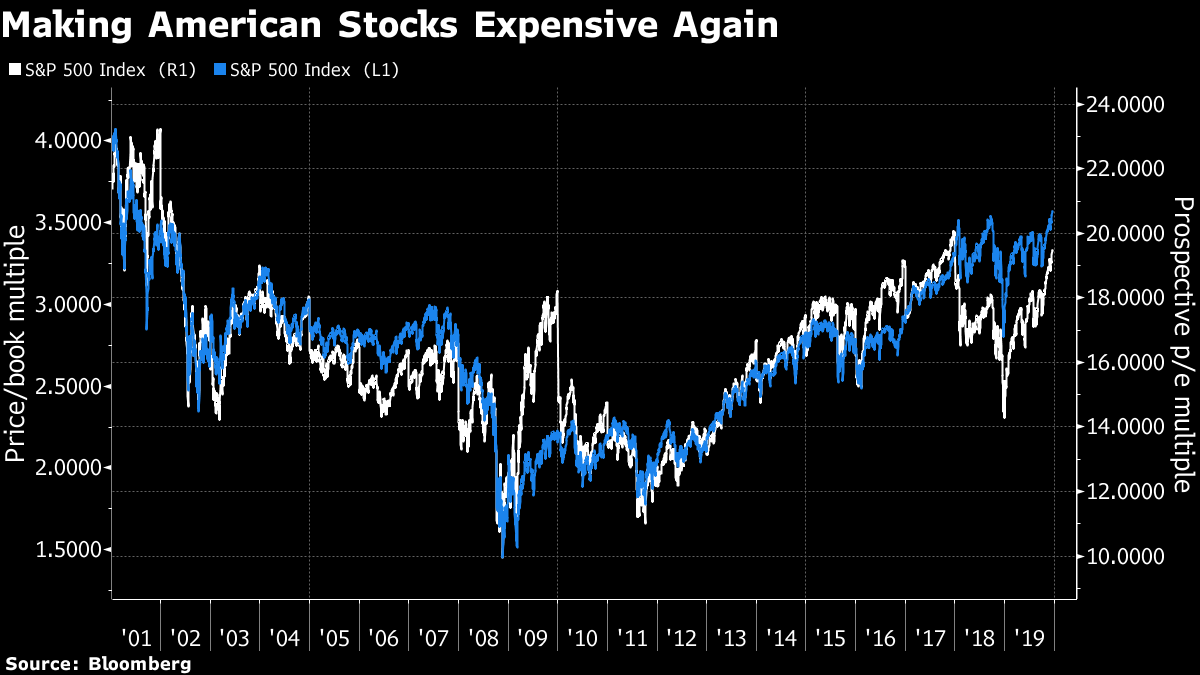

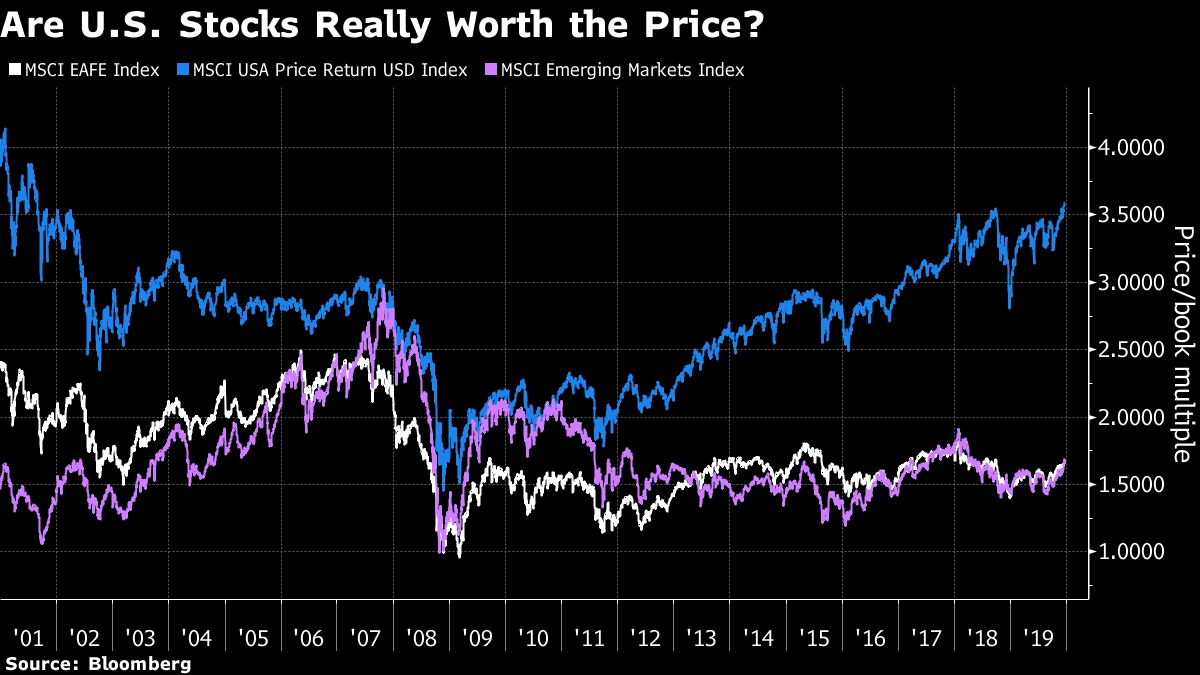

A Deflating Decomposition The year is ending on a bullish note, on the back of some news that should genuinely cause good cheer. But if we decompose the sources of growth in U.S. share prices, and in companies' earnings per share, it soon grows apparent that a lot of the good news in 2019 had already been factored in. Decomposing soon deflates the bubble of optimism about further gains. The following charts, produced by Deltec Bank & Trust Ltd., tell the story. Earnings per share have declined this year. All of the market's price growth is attributable to higher price-earnings ratios. Falling bond yields can justify a higher multiple on stocks, according to the ancient Fed model. But it seems strange to be increasing them to such heights, at a point likely to be near the end of the cycle. As for earnings per share growth itself, it would be much worse were it not for share buybacks. Investors are paying expanded multiples for poorer quality earnings.  As always when looking at the year in markets, we need to mention the health warning that share prices tanked at the end of 2018, taking multiples with them. Bloomberg's prospective P/E for the S&P 500 hit 14 in early January. It is now 19.5 — but that rise sounds much more reasonable when we note that the ratio started 2018 at 18.5. Even so, with the exception of a few weeks at the top of the stocks melt-up prompted by the passing of the tax reform package at the end of 2017, prospective multiples are at their highest since 2002. For stock indexes to set new records, they are going to have to surpass that level. Meanwhile, if we look at price-book multiples, the S&P ends the year trading at 3.5 times book, a level it hasn't reached since before the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001.  It is true that the market has looked expensive for a while, and continued to rally. But that argument grows ever more stretched. Investors do have alternatives. Here is the price-book multiple of the MSCI US index (which is very similar to the S&P 500) compared to those for MSCI's EAFE index, covering the rest of the world, and its emerging markets index.  Yes, it has been possible to make the same argument every year for a decade. But at some point, people will ask whether they really need to pay such a big multiple for U.S. stocks when equities can be bought so much more cheaply anywhere else.

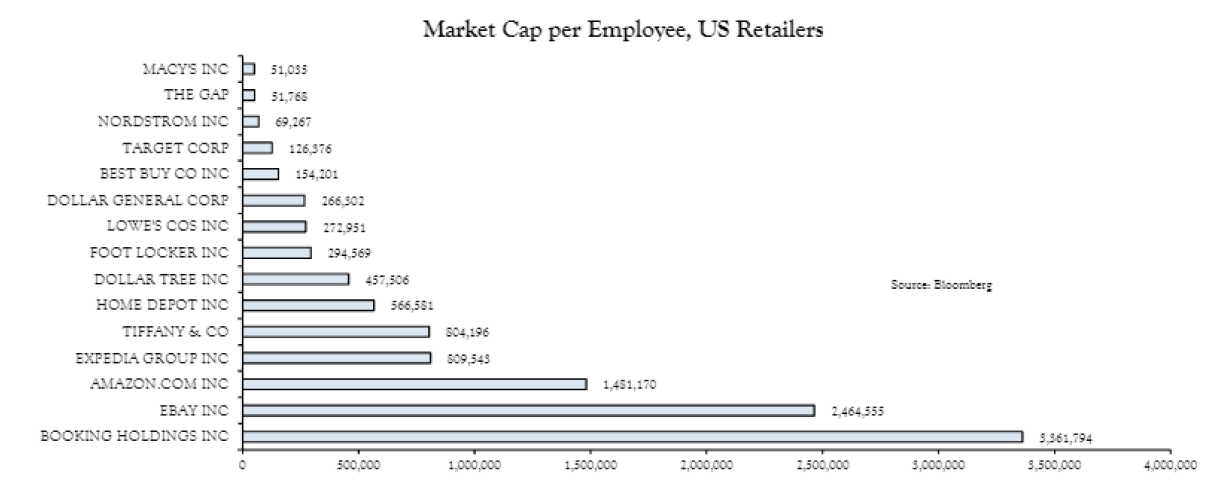

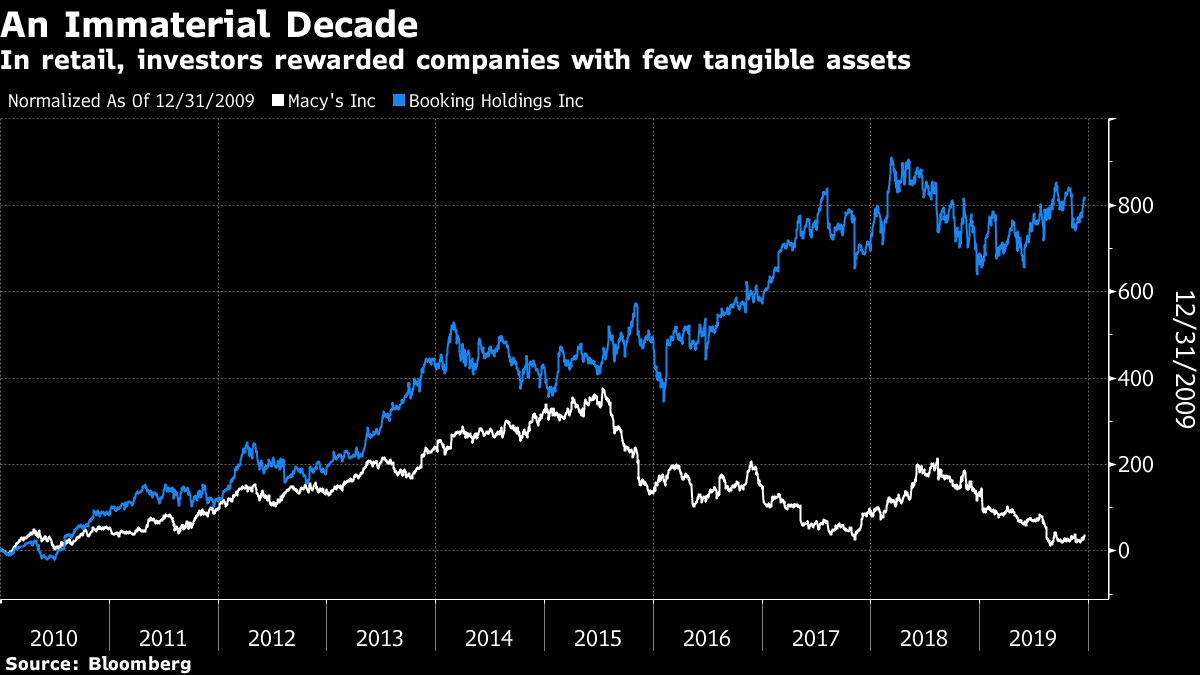

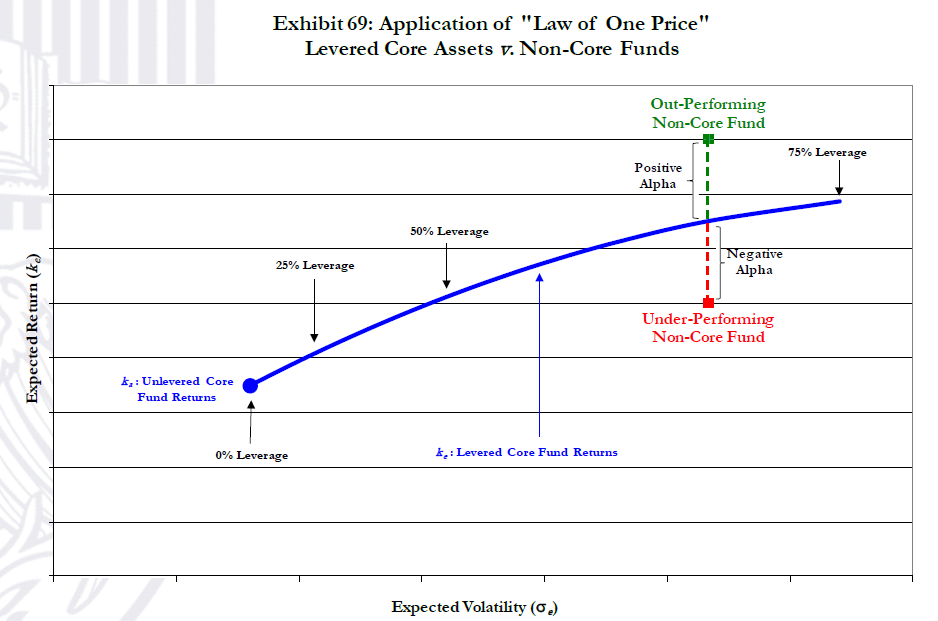

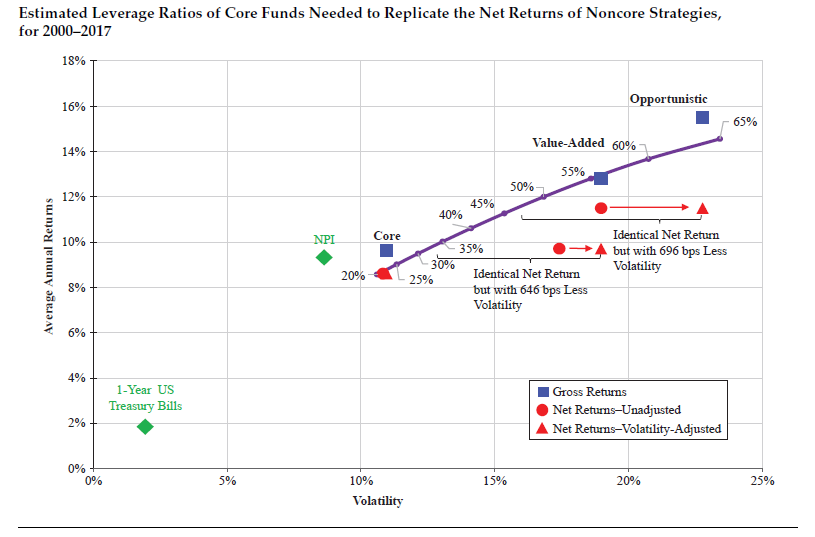

One of the most important trends of the 20-teens has been immaterialization. Tangible assets, such as people or physical property, matter ever less. And nowhere is this clearer than in the world of retailing. These numbers, produced by Vincent Deluard of INTL FCStone Financial Inc., show the amount of market cap per employee for a range of U.S. retailers. Each worker for Macy's Inc., whose stock is currently very much out of favor, accounts for only $51,000 in market cap, while The Gap Inc. and Nordstrom Inc. are scarcely any bigger. Amazon.com Inc., at $1.48 million per worker, gets much more out of its employees. But Amazon, originally conceived by Jeff Bezos as an immaterial "middle-man" company with virtually no assets, now has plenty of bricks and mortar. Booking Holdings Inc., parent of Kayak and Priceline, gets the most bang from its employees, at $3.5 million each.  Unsurprisingly, this has translated into fantastic performance for immaterial companies. This is how Booking has performed compared to Macy's:  Catching this trend ahead of time would have been profitable. A "long Booking, short Macy's" trade placed on New Year's Eve 2009 and (wholly unrealistically) excluding transaction costs would have generated a return of 562%. A Sickening Realization There was a downside to the Great Realization — the big move by institutions at the beginning of this decade into real assets, especially real estate. Such a move made sense on many levels, but it involved experienced asset allocators, experts in bonds and stocks, having to learn about a new field of investment. And moving into new and unfamiliar territory always carries risk. Real estate, as I wrote yesterday, performed fine in the 20-teens. And many institutions had poured into the sector. But many chose to do so through private funds, rather than through publicly quoted real estate investment trusts. There are advantages for an institution in doing so, but new research published in the Journal of Portfolio Management by two professors at Chicago Booth School of Business, Mitchell Bollinger and Joseph Pagliari, suggests that they got a very bad deal. You can find a summary here. Over the years, institutions have moved increasingly from "core" funds (standard investments in established and occupied buildings) to the alternative categories of "value-added" funds (where the managers are actively involved in work such as major refurbishments or finding new tenants) and "opportunistic" funds, which often work more like property developers, starting with projects at an early stage. According to the Private Real Estate Association, core funds accounted for 70.4% of all private real estate investment in the U.S. in 2004, but this dipped as low as 53.2% in 2009, as institutions looked for ways to repair the damage after the crisis. In 2016, opportunistic funds took 21.4% of private real estate investment ($41 billion), and value-added 16.2%. As this chart shows, there is far more investment in more esoteric property funds now than there was at the start of the decade — possibly thanks to a desperate hunt for yield by pension fund trustees facing a serious deficit. The academics suggest that the institutions didn't get anything like the return they should have done for taking the extra risk. Leverage is always a crucial element in real estate investments, and in good years it straightforwardly raises returns. As leverage increases, so should both volatility and expected returns. This is a schematic diagram:  It makes sense for a core investment to be more heavily leveraged, because it is less risky, while opportunistic investments should make less use of debt. They are risky enough already. But instead, leverage in private real estate funds increases as the investments in those funds grows riskier. The following chart is the academics' estimate of how much extra leverage would need to be applied to core funds to match the returns recorded by the more esoteric funds. In all cases, the returns would be good, for much lower volatility than was in fact achieved by the value-added and opportunistic funds.  So the riskier funds did nothing that could not have been achieved, with less volatility, by borrowing more. That is something that pension funds themselves could do without the help of expensive fund managers. So what has gone wrong? One possibility is that the value-added fund managers aren't in fact doing a great job of what is a difficult and risky undertaking. More likely still is that they are getting away with overcharging. The recorded returns, in a period when real estate has done well, are fine. And the pension fund personnel themselves, relatively inexpert in real estate, don't see that they are being overcharged. It is all very similar, at a more advanced level, to the way retail investors were convinced to pay high management fees for active funds that in fact lagged the index; during an equity bull market, they scarcely noticed the difference, but since the crisis they have moved to passive funds in droves. The paper is worth reading. And big institutions moving into new asset classes need to remember that all the standard rules apply within that asset class; look at risk-adjusted returns, and don't over-pay for performance that is merely replicating the market. They have learned these lessons and routinely apply them in equities and bonds; but by Bollinger and Pagliari's calculations, their failure to apply those lessons in real estate has cost U.S. institutions $7.5 billion per year. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment