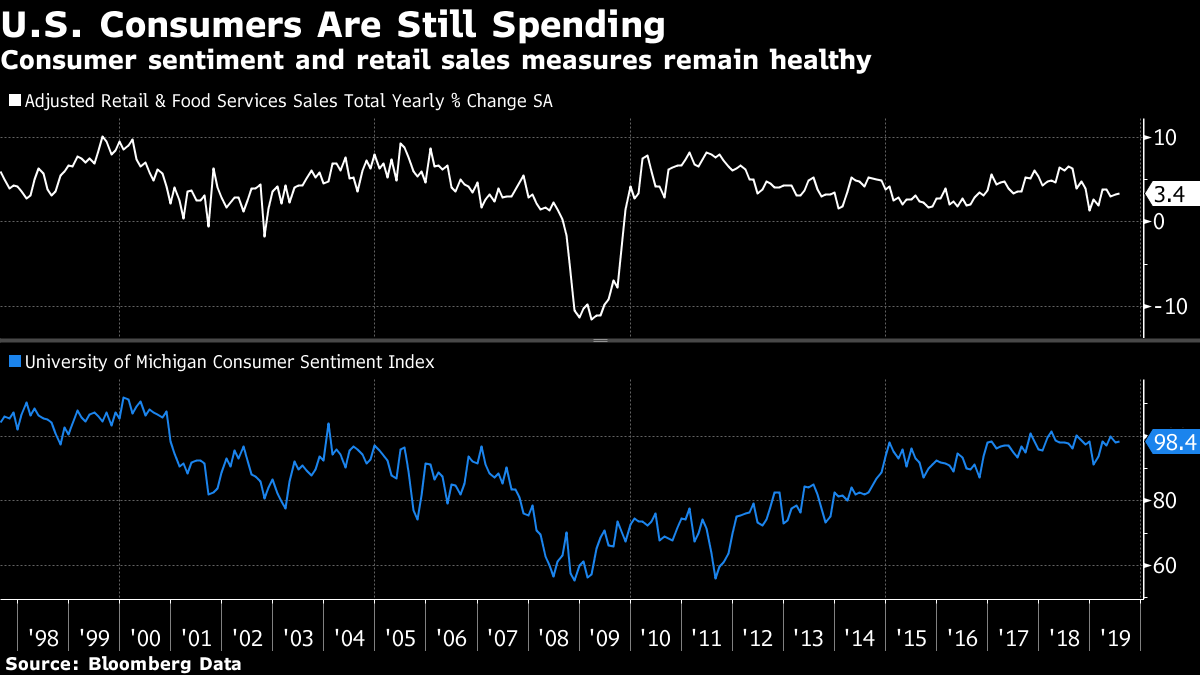

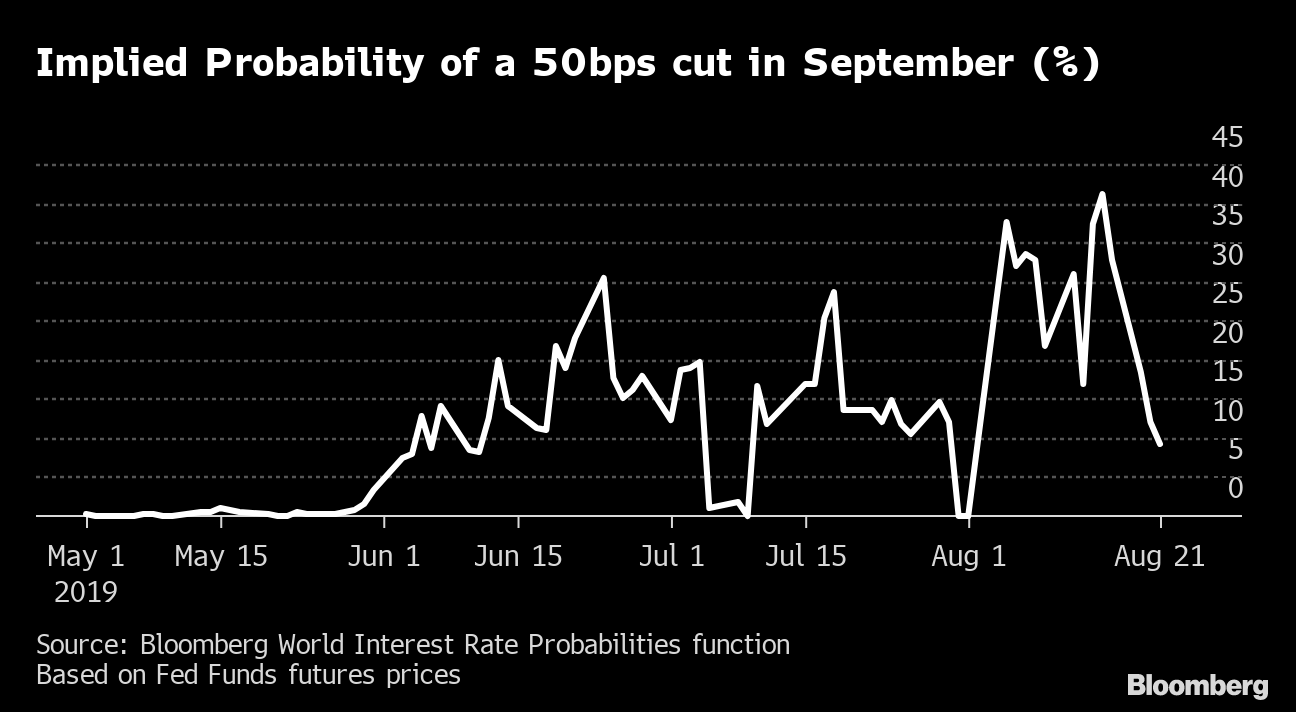

It's Amazon's World. Retailers Just Live in It. Some big U.S. retailers announced their results on Wednesday, and they were very good and better than expected. This reflects very well on the managers and employees of those companies, but it tells us little about what is happening to U.S. consumer demand. Everything is still distorted by the long shadow cast by Amazon. In this chart, the white line is the S&P 1500 index of U.S. retailers, a broad index of quoted retail groups. The blue line is the same index excluding Amazon. Both are rebased to start five years ago:  Obviously Amazon appears to inhabit a different planet. But note that the rest of the industry has not gone into total eclipse, even if it looks like a far less exciting investment once Amazon is excluded. And this year has seen a fascinating process of sorting out exactly who has a good strategy for dealing with the advent of Amazon and who doesn't. As the following chart shows, Target has had a fantastic year, crowned by its latest results. Walmart has kept pace with Amazon, and both have had a good year. Macy's catastrophic share price decline suggests that Retailpocalypse is truly here.  This has also been the year when Amazon — much like the other so-called FAANG stocks — has at last gone off the boil. This chart shows how the retailing sector minus Amazon has performed relative to Amazon over the last 12 months. It is normalized at 100 and ends at 101, so the one has beaten the other by only 1% over the year, essentially a dead heat.  But the stock market is looking at the health of retailers' profits, which is not the same thing as the health of the consumer or the size of the brick-and-mortar retailing sector. To get a good handle on that, we can look at the Bloomberg index of real estate investment trusts' investment in regional malls, in white below. At one point, mall REITs would move roughly in line with non-Amazon retailing stocks. But for the last three years, brick-and-mortar retailers have reinforced their share price in large part by abandoning bricks and mortar. The surviving retail groups may be leaner and meaner, but the retail sector as a whole has taken a bruising that can be expected to have lasting economic effects:  Meanwhile, broader economic measures of the health of the retail sector suggest what many might expect: The U.S. consumer is not at all stricken but may be in somewhat deteriorating health. This chart shows retail sales growth and the University of Michigan consumer sentiment survey, going back over the last 20 years:  The consumer is not yet behaving in a way that should arouse fears of an imminent recession. But the great results by Target and others do not provide us with any useful evidence. For the time being, the impact of Amazon on the sector is still far greater than the impact of any growing fear of recession. Powell Walks the Tightrope. We have more insight into the Federal Reserve's thinking! And it has had remarkably little impact on the market. The minutes to last month's meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee were released on Wednesday afternoon and appeared to bolster the relatively hawkish interpretation that Fed Chair Jerome Powell advanced at the time. The decision to cut the fed funds rate by 25 basis points was a "mid-cycle correction" and should not be seen as part of a sustained campaign of rate cuts. Events have intervened, and the 10-year Treasury bond yield has fallen almost 50 basis points since then. The minutes barely had any effect on the new consensus that the Fed will have to keep cutting rates. The minutes did push up yields slightly, but the 10-year continues to yield less than 1.6%, an almost inconceivable outcome a month ago. There are some good reasons for this. We have a big set-piece speech from Powell to look forward to on Friday. That will be a big deal— and it will be hard-going-on-impossible for him to satisfy market expectations without looking outrageously inconsistent. And of course the minutes look backward. We already had guidance on what had been said at the meeting, and they tell us nothing at all about the Fed's response to the dramatic developments that followed. This is my favorite measure of the level of uncertainty and noise that has been created by a presidential tweet imposing new tariffs, which came a day after the last FOMC meeting. It shows the implicit probability placed on a 50 basis point cut at next month's meeting, as derived from the prices of fed funds futures. This would be a significant financial event. Usually, the Fed and other central banks are able to corral expectations as the date of a meeting approaches. But not this time:  Powell succeeded in cutting expectations of 50-point cut to zero; and then Trump managed a day later to push them up to more than one-in-three. Since then the odds of a big cut have moved in line with the trade headlines and with the developing horror show in world markets. Such conditions have a chilling effect on the economy. It's hard to make business decisions in the face of such uncertainty. We have heard that pessimistic media reports on the economy can create their own reality, which is a fair point. The same is true of wildly varying prospects for drastic changes in monetary policy. Two questions remain. First, is it good or bad that equity markets have taken all of this with such equanimity? Equity volatility as measured by the VIX index is currently at 15.8, below its 200-day moving average. It has been more than double that three times in the last five years. Can such confusion over monetary policy really co-exist with relative calm in a stock market that is looking overvalued? And second and more important: How can Powell possibly give the market enough of what it wants to hear to avoid an accident (such as a sharp increase in yields) without sacrificing his credibility? Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment