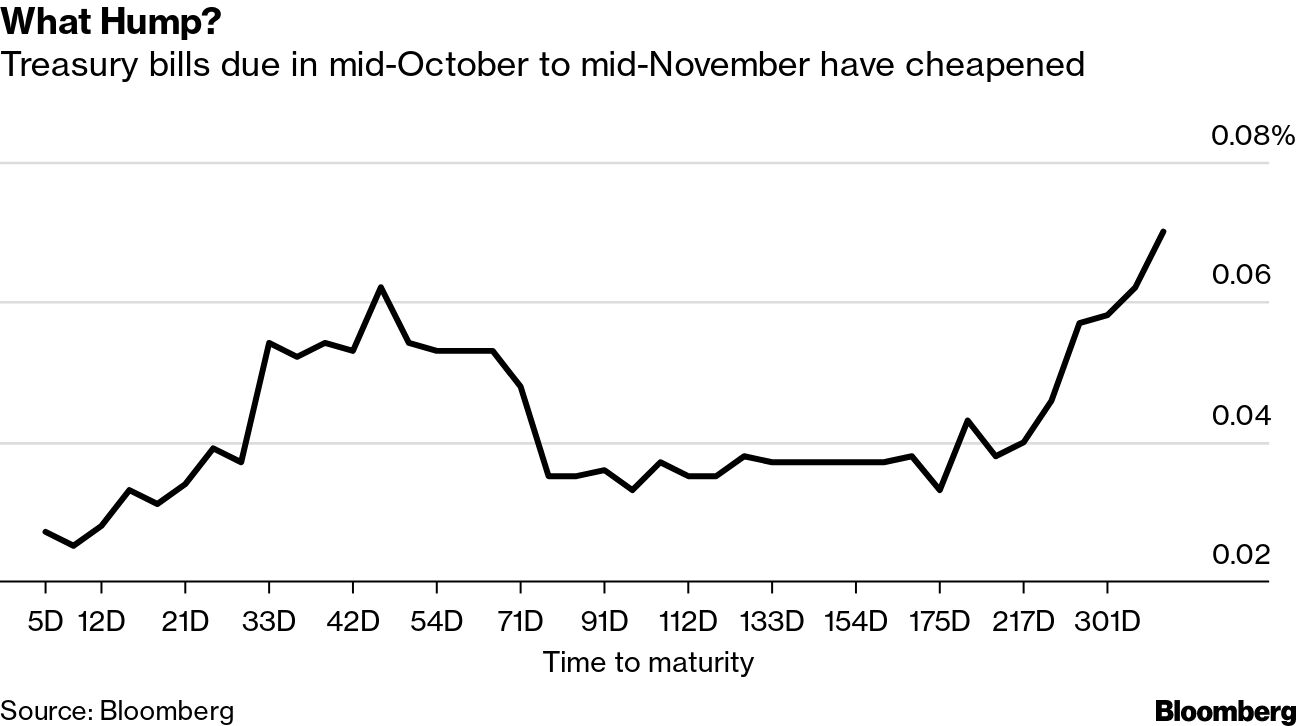

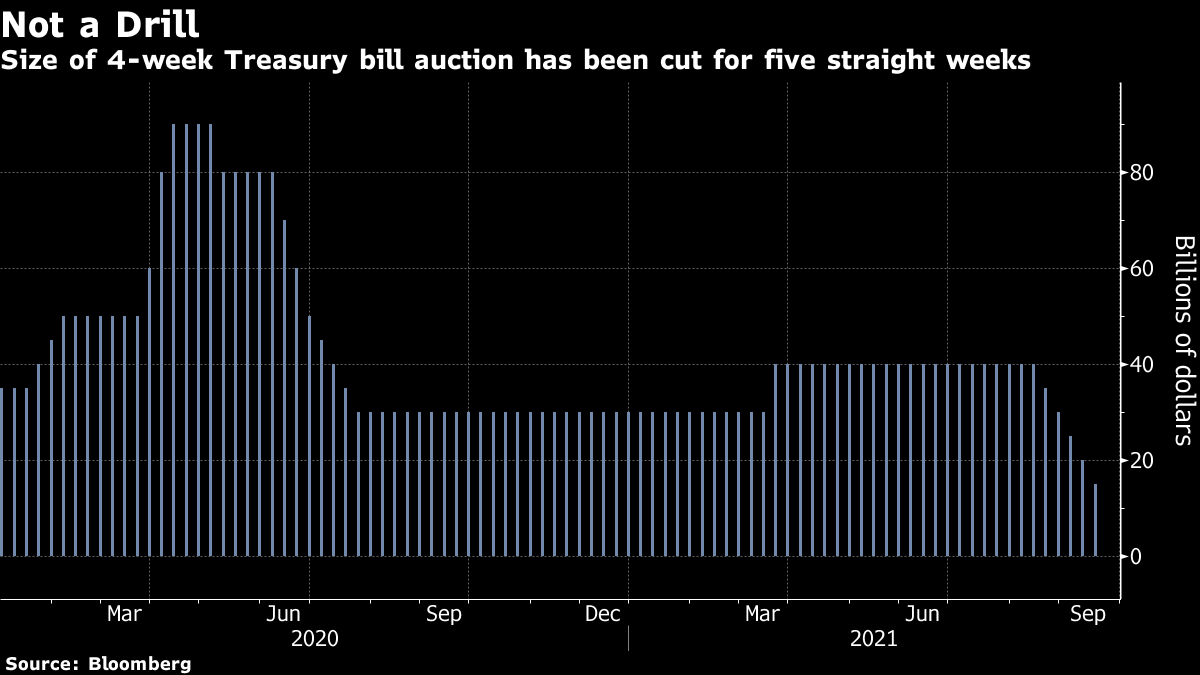

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter normally narrated by the cheery tones of Katie Greifeld. This week you're stuck mainly with me, Elizabeth (a.k.a. Beth) Stanton, a dour editor for rates and foreign exchange coverage. The U.S. Treasury yield curve -- in this case the difference between the yields on the five-year note and the 30-year bond -- got squashed this week, approaching 100 basis points for the first time in about a year. The proximate catalyst, on Tuesday, was the August consumer-price index, which rose less than expected. The year-on-year growth rate for core consumer prices (excluding food and energy) slowed to 4%, extending its retreat from 4.5% in June, which was the highest since 1991. Initially, five-year yields fell the most, on the logic that ebbing inflation means the Fed can wait longer before starting to put the brakes on the economy by adjusting its asset purchases and interest rates. But within about an hour, the downward momentum shifted to the 30-year yield, which got to within about 105 basis points of the five-year, reflecting declining inflation expectations. A favorable supply-and-demand picture for long-maturity Treasuries contributed. The September 30-year bond auction was so enticing to investors that dealers were left with the lowest-ever share on record (13.1%). There were no Treasury coupon auctions this week, and halting legislative progress on the $3.5 trillion tax-and-spending plan sought by President Joe Biden quelled anxiety about the longer-term supply outlook.  Meanwhile, the shortest-maturity Treasury debt securities are getting bent out of shape over the possibility that the federal debt ceiling won't get raised or suspended in time to ensure timely payment on bills maturing in mid-October to mid-November. This risk was reinforced by the unsurprising rejection of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen's appeal for a bi-partisan resolution. The yields on those bills, which under normal circumstances would be lower than yields on bills maturing later, have soared (to the extent that anything soars when the Fed's rate is nil). So the yield curve for bills, instead of sloping upward like a normal term structure would do, looks like this.  The Treasury Department has been cutting the size of some bill auctions in an effort to forestall hitting the debt cap. The four-week bill has gotten the most severe shearing, shrinking by $5 billion a week for five straight weeks. It may not be enough, if things go down to the wire, Wrightson ICAP economist Lou Crandall, an expert on Treasury finance, warned this week. Though he expects the U.S. debt level to remain under the ceiling until Oct. 22, allowing the 3- and 10-year note and 30-year bond auctions tentatively scheduled for Oct. 12-13 to go forward as planned, you might as well forecast the weather a month out. Crandall says a collision with the debt cap during the first half of October can't be ruled out, and could force a postponement of those auctions.  Which brings us back around to the outlook for Fed tapering. If the debt ceiling problem hasn't been solved by November, Guggenheim economists Brian Smedley and Matt Bush argued this week that an announcement on tapering is likely to be delayed to December, and that Treasury yields could fall further as a result. Gary Gensler, the new chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, used his first appearance before the Senate Banking Committee to talk in part about market structure-based projects the agency is taking on across the financial markets, and in doing so dredged up some painful memories for the Treasury market. The market-structure projects also span equities, swaps and crypto in addition to the credit markets, where he said greater efficiency and transparency is needed generally. Regarding Treasuries, Gensler called out the U.S. government bond market for its several face-plants in the past decade: the liquidity breakdown in March 2020 that caused the Fed to launch its latest asset purchase program; the September 2019 surge in overnight funding rates that resulted from an onslaught of new Treasury securities landing on dealers' balance sheets just as cash was being sucked out by quarterly tax payments companies needed to send to the government; and, of course, the October 2014 "flash crash" in yields that spawned a 76-page analysis the following year. Gensler expressed interest in proposals that have been made to bring central clearing to both cash Treasuries and repo, and in "how to level the playing field by ensuring that firms that significantly trade in this market are registered as dealers with the SEC." That's an apparent reference to the principal trading firms (PTFs), high-frequency traders that handle about half of the volume in the Treasury market. Gensler referenced work completed earlier in the summer by former Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, whose Group of Thirty (!) panel of former economic policy makers recommended, among other things, an expanded role for central clearing. It's unlikely to come about, advocates have argued, without a regulatory mandate. Katie Greifeld here. I'm making a cameo to talk about one of my favorite things: Bitcoin bonds, kind of. Cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase Global Inc. came to market with its debut junk bond sale -- amid some amusement by the fact that last week, Chief Executive Officer Brian Armstrong seemed to ask what a bond is, which led to predictable responses on Twitter. In any case, there was a ton of demand for these particular bonds. Coinbase's $1.5 billion offering was quickly boosted to $2 billion after investors threw $7 billion at the sale, Bloomberg News reported. The issue was split between seven- and 10-year bonds, which sold at interest rates of 3.375% and 3.625%, respectively-- lower than the initially discussed borrowing costs, other people familiar with the situation said. This newsletter had discussed how much demand there is for bonds of any size and shape right now, even as analysts continue to hammer on about TINA -- there is no alternative to equities -- with rates so low. But even still, the Coinbase bonds probably drew organic demand, in the eyes of Family Management Corp.'s David Schawel. "There's demand for bonds in general, but investors probably thought this deal came cheap on a relative value basis," said Schawel, the firm's chief investment officer. "So high demand from initial price talk that came cheaper than expected." Since pricing at par on Tuesday, the Coinbase bonds have fallen for two days straight, underperforming other similarly rated junk bonds. Of course, it's been a tough week for Coinbase -- last week, the exchange found itself in the crosshairs of U.S. regulators for plans to roll out a product that would allow users earn 4% by lending their tokens. That's likely weighing on the bonds, Schawel said. "With the headline and regulatory risk, the creditworthiness versus ratings will be heavily debated and will likely trade in a volatile manner going forward," Schawel said. So it'll be fascinating to watch these bonds going forward. We know that Coinbase's equity tends to track the price of Bitcoin, especially on Mondays -- it remains to be seen whether the bonds become a crypto proxy as well. China Evergrande Group crisis escalates Bank of England rate hike expectations climb Inflation expert lofts giant floatie |

Post a Comment