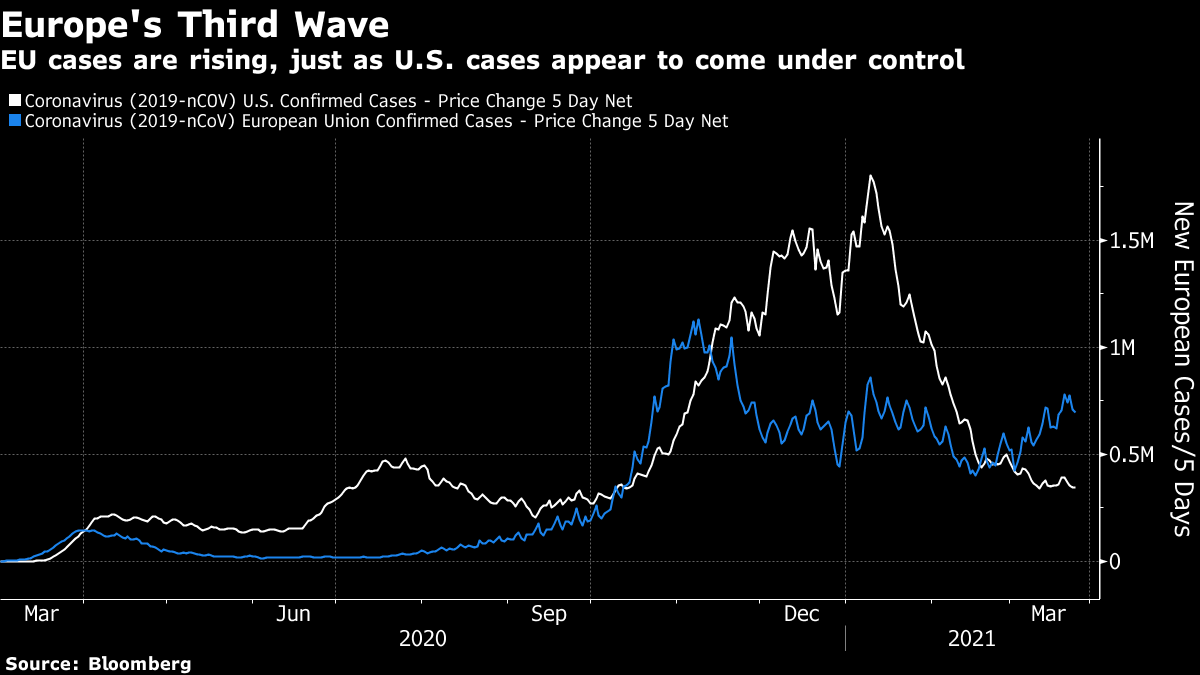

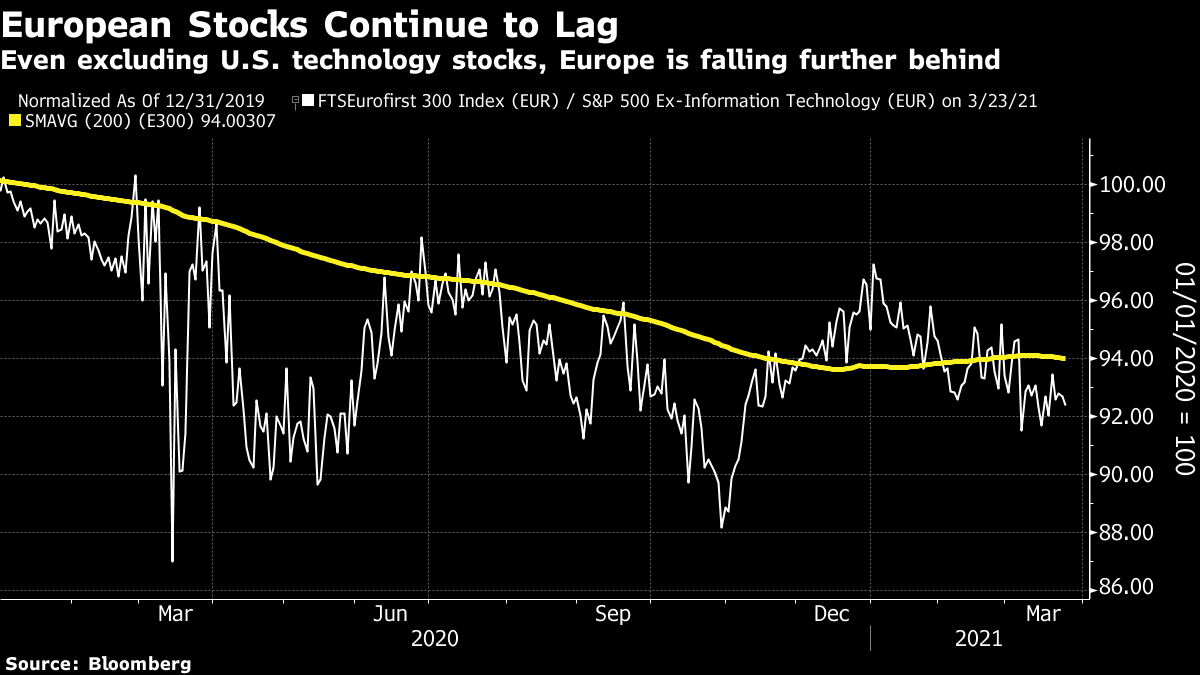

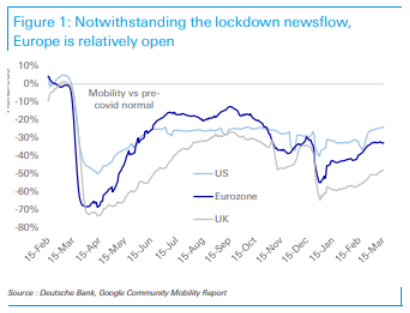

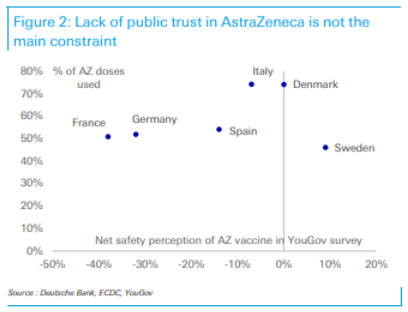

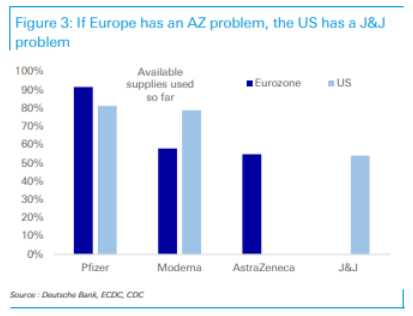

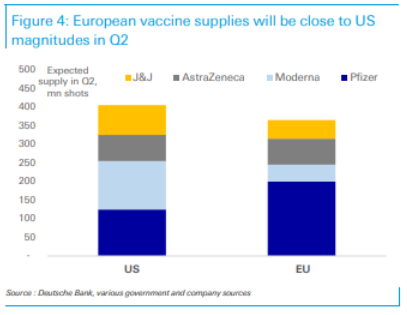

Putting Europe to the TestOne of the strongest market trends of the last 12 months appears to have broken. The euro is no longer on a consistent upward path compared to the dollar, and this has ramifications for virtually everything else. A weaker dollar makes life easier for emerging markets, and for the U.S. It also makes U.S. inflation that much more likely. Beyond that, it more or less directly implies that Europe is a better investment for now than the U.S. There have been enthusiastic bets on all of these things. So how seriously should we take the change in the trend? There is a lot of pseudo-science in technical analysis, which can make analyzing chart patterns look much more complicated than it is. But the tale of the euro is clear. It has just dropped below its 200-day moving average for the first time in 10 months, is at its lowest since last November, and is no higher than it was in July. Optimism about a stronger euro is being put to a rigorous test:  Why? The clearest reason is the virus, which still dominates all of our lives. The broad narrative of the European struggle with the pandemic and how it compares with Americans' battle on the other side of the Atlantic is roughly accurate. Neither has done as well in combating Covid as countries with wealth and advanced health systems should have done, but the EU record has been appreciably better throughout. That is now beginning to shift. The chart below shows the number of new cases recorded each five days. To allow an easy comparison, I multiplied the U.S. number to account for the EU's larger population. Europe succumbed to its second wave a little ahead of the U.S., but this is the first time since Covid-19 appeared that new cases have risen in the EU while falling in America. This is plainly concerning.  The second big reason is wrapped up in the bond market and expectations for inflation. Treasuries tend to yield more than German bunds, and hence attract funds to the U.S., strengthening the dollar. This differential plummeted in the first month of the Covid scare — but at 2 percentage points it is now roughly back to where it started last year. The dollar has strengthened with it. The market has more confidence in the Federal Reserve's ability to create inflation than it does in the European Central Bank's, and so the dollar is rising:  The general weakness of corporate Europe doesn't help. European stocks have looked cheap for a while (as I have argued), but this hasn't helped them. Even if we adjust for the dominance of Silicon Valley by comparing the FTSE-Eurofirst 300 with the version of the S&P 500 that excludes information technology, we still find European stocks steadily lagging the U.S., in common currency terms:  So, the narrative has turned against the EU. The heart of that, obviously, is the difficulty the region is having with its vaccine rollout. There is no question that the EU is off to a much slower start than its counterparts across the English Channel or the Atlantic. But it is possible that the narrative is being overdone. The future of the euro for the next month or two — or, in other words, the chance that it settles into another declining phase and really messes up the calculations of the many people who were positioned for a steadily weakening dollar this year — probably depends on whether the EU can visibly sort out its vaccine program. George Saravelos and Robin Winkler of Deutsche Bank AG have made an interesting attempt to question this narrative. First, they make the point that Europe isn't totally locked down at present. Using the Google mobility data to which we have all become accustomed, it is now only slightly behind the U.S. (although the news of a fresh and very tight lockdown in Germany may change this). The U.K., the developed economy with the most successful vaccine rollout to date, also continues to have the tightest restrictions on economic activity:  As has been widely reported, Europe is very "vaccine-hesitant," with many doubting whether it is a good idea to get the jab. Last week's mess, in which most of the EU's largest countries halted AstraZeneca Plc vaccinations because of concerns over blood clots, raised fears that public trust has been lost. But Winkler and Saravelos point out that there is no particular relationship between perceptions of the AstraZeneca vaccine's safety and the rate of take-up. Sweden is far less vaccine-hesitant than France, but has used a smaller proportion of its doses:  They also point out, reasonably, that the problems for AstraZeneca in Europe could easily be repeated with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the U.S. Like the AstraZeneca shot, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is cheap (and indeed only needs one shot), and should come in plentiful supply — but the statistics published to date imply, rightly or not, that it is inferior to the alternatives currently available. There is no precedent for the availability of rival vaccines using different technologies, and the U.S., like European authorities, may yet find that it has difficulties persuading people to take the J&J vaccine. If this happens, it would tend to weaken the dollar.  Finally, the EU's much criticized procurement effort should be about to catch up. By the end of June, it should have almost as many vaccine shots available as the Americans do, including a lot more from Pfizer Inc. Note, however, that the EU's population is more than a third bigger than that of the U.S., even after Brexit:  Last week's AstraZeneca suspension and the increasingly nasty nationalist rhetoric over how to improve vaccine supplies have unquestionably shaken confidence in the EU, and with it the euro. That, it seems to me, is a reasonable response to a dreadful and potentially tragic situation. Immunity appears not to last forever, and so speed is of the essence if the continent is to achieve the herd immunity that would stop the virus from spreading. Still, the fight has taken many unexpected twists already. Many heroes of public health who dealt with one pandemic stage have been brought low months later by the next — and vice versa. If the EU can turn around its vaccine campaign, the chances are that the euro can turn around as well. But the narrative is getting entrenched, and it needs to turn the story around soon. Inflation ConflationI'm pleased to say that the debate over demographics and inflation, and in particular over what Japan teaches us about the future, is intensifying. One approach I hadn't heard before comes from Simon White of Variant Perception. It takes a monetarist perspective, and borrows from Swiss economist Peter Bernholz's Monetary Regimes and Inflation. According to Bernholz, two crucial thresholds were crossed before all the great 20th century inflations and hyperinflations took hold. The first was that the budget deficit as a percentage of government expenditures (the "budget deficit ratio") exceeded 20%. And the second was that the central bank was monetizing most of these expenditures. Surprisingly, Japan has at no point in the last three decades passed both of those thresholds at the same time. Its budget-deficit ratio was at or above 20% for several years between 2017 and 2020, and its monetization ratio was at over 90% around 2016, but crucially it has never had both ratios past their thresholds at the same time for a sustained period. Thus, Variant Perception contends, Japan hasn't truly crossed the Rubicon, and cannot be taken as evidence that monetizing large government deficits isn't inflationary: The fallout from the pandemic may eventually put this to the test.  As White points out, the current projected fiscal stimulus implies a budget deficit ratio of at least 20% in a year's time, while the Bank of Japan could be forced to pick up the pace of monetization once more. This puts Variant Perception ultimately in the camp that believes a new inflation regime has arrived: None of this means inflation is imminent, but it means the "regime" has changed, and vanilla rises in inflation are more likely to lead to unanchored and disorderly rises in prices, rather than peter out as they have done for most of the past 30-40 years. First Japan, then potentially other developed markets as the lines between fiscal and monetary become ever more blurred.

Globalizing the Philips Curve

Another issue concerns globalization. A key reason for believing that inflation is about to rise comes from the Phillips Curve, which in simple terms posits a trade-off between unemployment and price increases. Reducing unemployment, as policymakers are determined to do at present, will lead to higher inflation, all else equal. But all else isn't equal, and for the last four decades at least we've had steady globalization. That means that in an open economy, fewer workers doesn't mean higher pay, it means a greater likelihood that employers will look overseas. Indeed in Germany, unions negotiate to maintain jobs at the expense of wage rises, because they are aware of competition from abroad. Thomas Aubrey of Credit Capital Advisory in London shows that over time in the U.K., the curve is flatter (meaning there is less of a trade-off) when the economy is more open to trade. And it is a process that can repeat itself. Aubrey points out that textiles jobs in China are leaving for cheaper countries, now that wage demands are growing. All of this suggests that the critical variable to watch in the next few years concerns trade policy, rather than fiscal or monetary policy. If the world really does reset into two rival blocs that attempt to minimize trade with each other, as is possible if U.S.-China relations come out at the worse end of expectations, then the logical consequence would be a return of inflationary dynamics to the West.

Further thoughts on inflation continue to be welcome.

Survival Tips

How to survive when you're quoted by a very conservative podcaster whom your very liberal daughters cannot stand? I have some insight into this, as I had the privilege to be featured by Ben Shapiro on his show on Monday. You can hear him cite my arguments about the possibility of a new inflationary regime at 20:19 of this podcast. As the episode is entitled "Biden Falls Down the Stairs" you can understand why liberal New York teenagers would have a problem. For the record, Shapiro quotes me accurately, and his commentary is fair. I have no complaints. So how to deal with the problems this has created for me as a father? By also sharing this clip, of an interview he gave to Andrew Neil on the BBC in 2019. Some context for non-Britons who might not have heard of Neil: He is one of the country's most famous journalists, and a redoubtable figure of the right. He came to fame editing the Sunday Times newspaper for Rupert Murdoch, then set up the Sky News cable channel for him, and more recently has headed the Spectator — Britain's longest-established conservative periodical. He has much the same visceral effect on young liberals in England that Ben Shapiro has on my daughters. The difference between the two is that Neil studies his interviewees and asks questions that are designed to challenge and provoke — even if it involves taking a position with which he himself doesn't agree. Shapiro didn't grasp any of this, admitted to knowing nothing about Neil, and embarrassed himself. So, I have two tips. First, never go into an interview without knowing something about the person who will interview you. And second, if someone asks you a question you don't like, control the instinct to respond by attacking the questioner. Rather than impugning their motives, answer the question as well as you can. All of us would be better off this way. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment