Keynes and HousesIt looks like Keynes was right. Before that comment inspires a chunk of the readership to fire off angry emails about macroeconomic policy, I should say that I am not talking about John Maynard Keynes's influential ideas about how to stimulate the economy. Rather, I am talking about his role as a trail-blazing investor and the father of modern endowment management. Between the wars, Keynes was bursar of King's College, Cambridge, one of the richest in England, and had the freedom to deploy the considerable assets in its portfolio. Until then, Oxbridge endowments had been invested almost entirely in real estate, but Keynes decided it was worthwhile moving into other assets, because property was riskier than it looked. He made this prescient comment: "One must not allow one's attitude to securities which have a daily market quotation to be disturbed by this fact or lose one's sense of proportion. Some Bursars will buy without a tremor unquoted and unmarketable investments in real estate which, if they had a selling quotation for immediate cash available at each Audit, would turn their hair gray. The fact that you do not [know] how much its ready money quotation fluctuates does not, as is commonly supposed, make an investment a safe one."

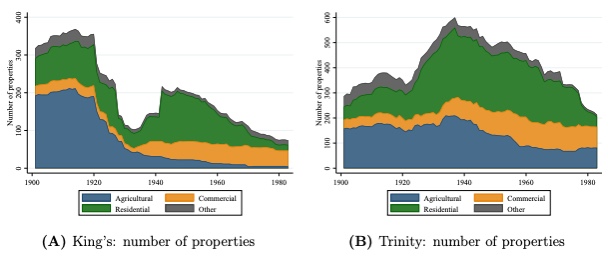

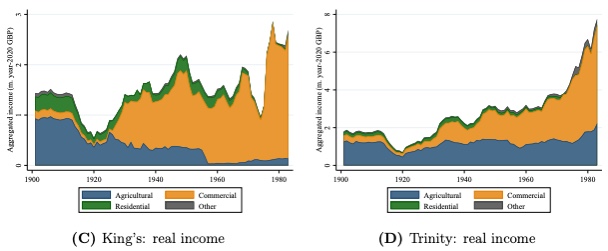

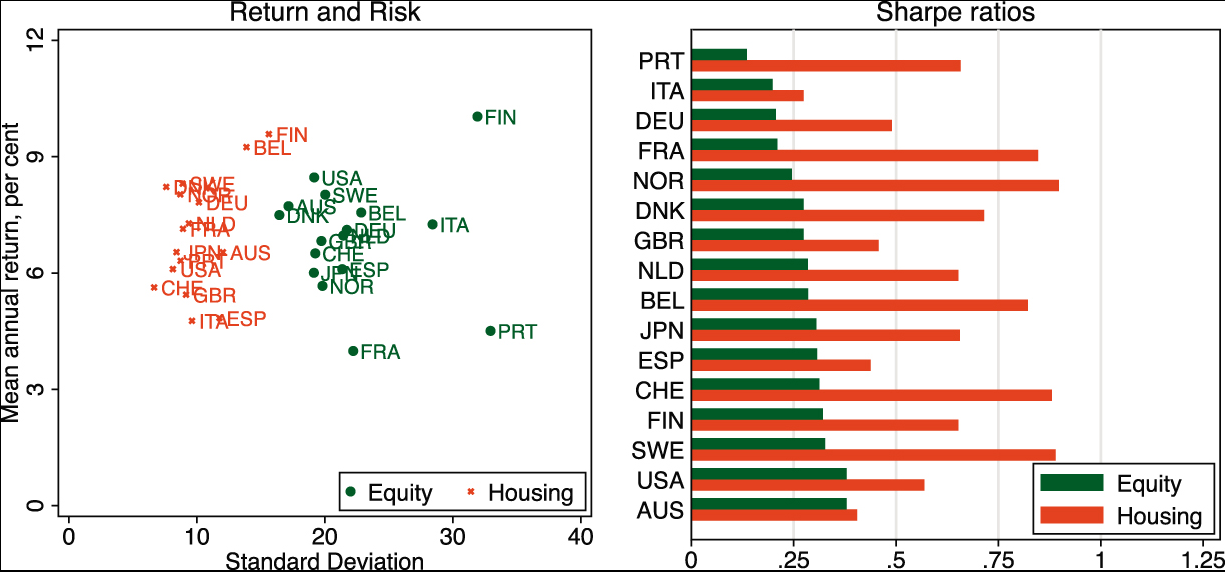

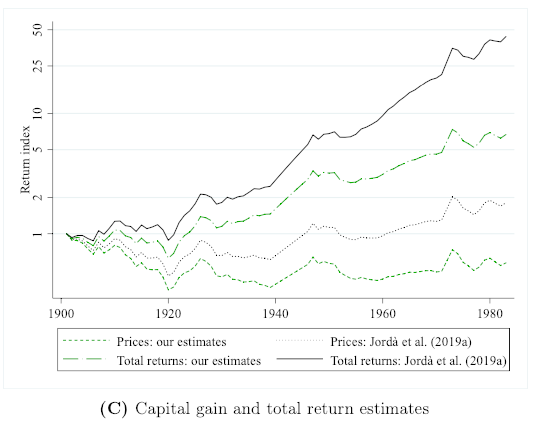

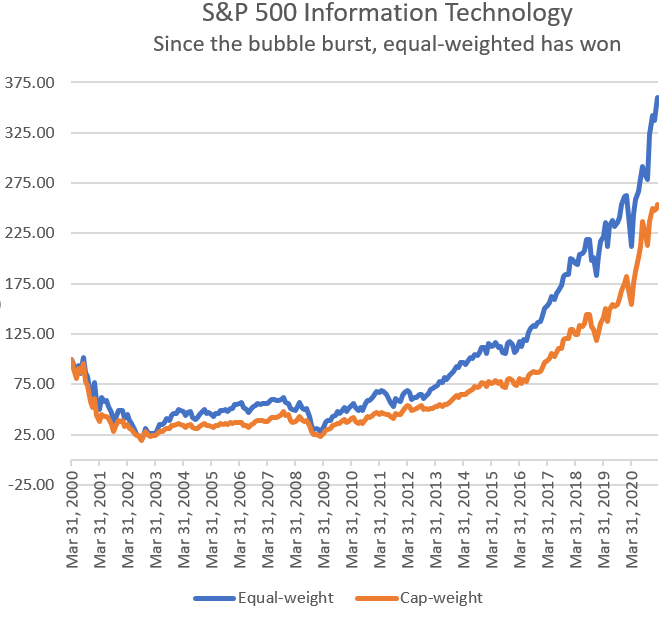

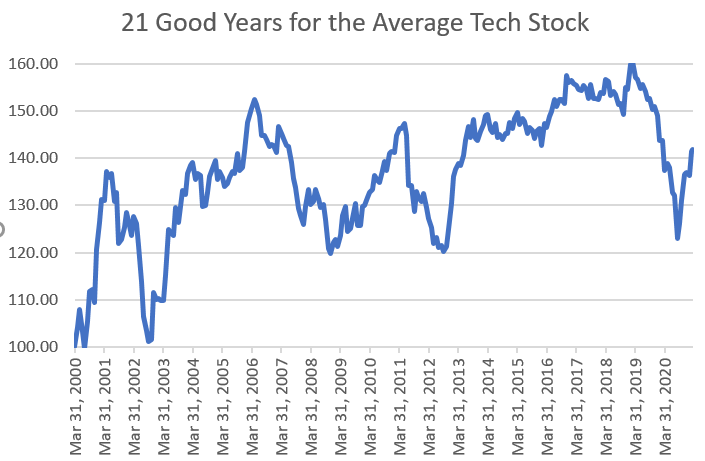

Whatever you think about his ideas on macroeconomics, this point is very true. And he was prepared to put his money where his mouth was. This shows up clearly in a new paper called The Rate of Return on Real Estate, by David Chambers of the University of Cambridge's Judge Business School, Christophe Spaenjers of HEC Paris and Eva Steiner of Penn State University's Smeal College of Business, which is based on data throughout the 20th century for the endowments of four colleges: New College and Christ Church, Oxford; and Trinity and King's Colleges, Cambridge. This cast light on the sharp difference between the King's property portfolio under Keynes, and the real estate holdings of neighboring Trinity. Both owned roughly the same number of properties at the beginning of the last century. It is easy to see in the chart on the left when Keynes took over at King's. Meanwhile, Trinity doubled down on property, becoming a major landowner, as it is to this day:  Keynes's adventures in the stock market in the 1930s proved spectacularly successful. In many ways he did for the U.K. what Benjamin Graham was doing in the U.S. But Trinity's management of its property portfolio was superb, aided in part by luck. For example, in the 1930s it bought farmland that would become the Felixstowe container port, the largest in the U.K., long before container shipping had been invented. Between them, the two colleges showed that there was a case for more modern asset allocation, but also one for a traditional actively managed property portfolio:  But while this is all very interesting, the meat of the report is devoted to details gleaned from a century's worth of housing returns. All the four endowments owned a lot of homes throughout the period, and kept records of their capital gains, rental income and costs. This gave the academics an unusually "clean" set of data to look at how much money really can be made out of residential real estate. The issue is important because it tends to conflict with a hugely influential study published in 2017, called The Rate of Return on Everything, by Oscar Jorda, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. This was a mightily ambitious piece of financial archaeology covering 17 countries, and it rendered the startling result that housing performed virtually as well as equities over time, but with much less volatility. The result held true for every country that Jorda and his colleagues examined:  This remarkable outcome suggested the cult of equity that took over in the second half of the 20th century was a big misjudgment; we should have been in housing for the long run instead. The research by Chambers and his team indicate otherwise. This is how their numbers for capital appreciation and total return compared with the Jorda team's data:  The real returns from housing largely depend on the rents that can be derived from them, and the Oxbridge colleges' real-world experience suggests that being a landlord is nowhere near as profitable as the earlier study made it appear. There are plenty of caveats. The Jorda study was based on broad national data. The Oxbridge colleges are all large landlords, but they probably aren't representative of the country as a whole. That said, they had the advantages that go with scale and talented employees. They were also actively managing their portfolio for profit, which isn't necessarily true of the housing stock as a whole. So if there were a discrepancy, you would expect the Oxbridgeans to come out on top. Why are the results different? Chambers suggests first that the Oxbridge "micro-study" involved taking both rents and prices from the same data. The earlier study unavoidably took price and rent information from different sources, rather than identifying the total return from a specific sample of houses. He also argues that it is necessary to control for quality; a four-bedroom semi-detached house built in 1980 will be much higher quality than one built a century earlier. Without adjusting for this, he argues that you can overestimate the returns from older housing. That leads to the critical issue of costs; landlords often discover that their business is much more expensive than they had expected. The costs of holding and renting a portfolio of housing will inevitably be higher than the equivalent costs generated by a portfolio of stocks and bonds, and the endowments' books capture this. The bottom line is that housing is restored to the position we might expect, with returns ranking between bonds and equities. Housing is lower risk than equities but, as Keynes surmised, once you look under the hood at volatility and expenses, it's not the free lunch it may appear. For now, as in other areas of life, the Keynesians have it. But, as in those other areas of life, I'm guessing there will be a strong intellectual counter-punch before long. Big Tech and Big MarketsYesterday I went through Rob Arnott's critique of the "delusion of big markets." His argument was that when people get excited about future growth, they forget there will be losers. Thus, every company is priced not only on the basis that big disruptive change will happen, but that it will be the big winner. In the case of electric vehicles, the market cap of EV makers has surged to almost equal the combined value of all traditional automakers; yet the market cap of the conventional manufacturers hasn't fallen. This is plain illogical. For another example, I cited the dot-com bubble, when people threw money at every new company in the hope of catching the winner. I offered the top 30 companies in the S&P 500 information technology sector in March 2000 as an example. Apple Inc. at that point was number 30. Many above it have either plummeted or disappeared as a result of Apple's subsequent rise. This prompted one reader to suggest that buying equal amounts of all those companies would have worked out. S&P Global kindly provided me with the performance of the equal-weighted and conventional cap-weighted versions of their information technology index back to March 2000. And, yes, the equal-weight version did very well, and beat the market cap-weighted version. But you needed to sit on losses for more than a decade before breaking even:  Equal-weighting is arguably the crudest form of "smart beta." A straightforward bet that the market was wrong about tech's winners, supplanted by crudely betting equal amounts on each, would do better, with Apple's gains more than counteracting the losses on companies like Nortel Networks Corp. But in absolute terms, buying at the top of a bubble wasn't the greatest idea. The equal-weighted index has been ahead of the normal version constantly throughout the last 21 years, with a strong tendency to do worse when markets are tense. The dominance of Big Tech in 2019 was a big deal, although there have been other periods when the biggest names in technology did well for a while:  If we want a better analogy for electric vehicles, an unproved but exciting technology just coming to market, we might prefer to look at the true "dot-coms" — the myriad start-ups that floated at the end of the 1990s, without ever having made a profit. Investors bought them all on the assumption they would be sure to catch the winner that way. Another reader pointed out that I tried some crude mathematics on this for the 10th anniversary of the Amazon.com Inc. IPO, for my old employers at the Financial Times. In 2007, Amazon had just unveiled excellent results, and its share price had surged. It was beginning to look like the Amazon of today, despite having tumbled more than 90% after the first bubble burst. The logic of buying everything in sight back then was beginning to look defensible. This is what I wrote: When pressed, investment bankers would argue that portfolio diversification justified the money going into dotcom IPOs. They did not know how the internet would pan out, they argued, but it was obviously a disruptive technology that would enable some players to win very big indeed. Thus, they said, the rational thing to do was to buy into lots of IPOs to increase the chances of catching a winner. Ten years on, it looks like that strategy worked.

Assume you had $1,000 and put $100 into Amazon's IPO and the rest into nine other IPOs that all went bust. You still would have made a return of 190 per cent, easily beating the S&P 500. Had you balanced your Amazon investment with equal investments in 13 other companies that went to zero, your return would have been identical to that on the S&P.

I don't have the time or energy to repeat the calculation now, but it's a fair bet that if you bought Amazon at IPO, you could by now have afforded to throw money away on even more startups that went to zero and still beat the market. So we shouldn't worry about the big market delusion after all? I wouldn't go that far, although the success of Amazon helps to explain why people are prepared to throw so much money at electric cars. Amazon in recent years has gone beyond the wildest dreams of its initial investors. After a closer look at the tech world of 2000, the argument that EV valuations are dependent on the delusion of big markets still stands. But we can understand more easily why so many people allow themselves to be deluded. Survival TipsWriting about Keynes gives me an excuse to extol the virtues of King's College's chapel. I once had to speak to a student conference at the college, and discovered to my alarm that the platform had a large bust of Keynes looking straight over my shoulder. It was unnerving. But the college and its students were wonderful, and I could visit the chapel. The chapel at King's is bigger than many cathedrals. To my taste it has the most beautiful interior of any British building that I know. It also has a remarkable acoustic. The college's famous choir unfortunately has to spend much of its time on a diet of rather twee British church music, but I found two videos, which you can find here and here, where you can listen to Bach's St Matthew Passion while treating yourself to a 360-degree view of the chapel. (Just go to the circle in the top left corner.) King's also put together a nice socially distanced Guide to the St Matthew Passion last year. To listen to the whole thing, which many of you might want to do with Easter approaching, you could try Nikolaus Harnoncourt conducting it at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw (peerless interpretation but the sound quality isn't great), or a more urgent interpretation conducted by John Eliot Gardiner at the Royal Albert Hall. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment