Banque WormsLast August, Citigroup Inc. wired $900 million to some hedge funds by accident. Then it sent a note to the hedge funds saying, oops, sorry about that, please send us the money back. Some did. Others preferred to keep the money. Citi sued them. Yesterday Citi lost, and they got to keep the money. I read the opinion, by U.S. District Judge Jesse Furman, expecting to learn about the New York legal doctrine of finders keepers—more technically, the "discharge-for-value defense"—and I was not disappointed. But I was also treated to a gothic horror story about software design. I had nightmares all night about checking the wrong boxes on the computer. The story—we have discussed it before—is that, in 2016, Revlon Inc. took out a seven-year syndicated term loan. Citibank N.A. is the administrative agent on the loan; it gets interest and principal payments from Revlon and passes them on to the lenders. Revlon ran into a bit of trouble and, as companies do these days, it did some creative stuff with its debt: In May 2020, it convinced some of the term-loan lenders to strip collateral from the term loan so it could be used to back new debt. The lenders who were part of this "incredibly aggressive" deal got to roll over into the new, effectively more senior debt; the other lenders were left with worse debt and got mad. Some of them got together to work on a lawsuit, which they filed on Aug. 12. Twenty hours before they filed the lawsuit, though, they got lucky: Citigroup just wired them all their money. They received wire transfers for the full amount of principal and accrued interest they were owed on the loan. Their first reaction was mostly "well this is weird, I guess Revlon decided to pay off the loan rather than fight about it." Their second reaction, after Citi sent them frantic notices saying it was a mistake, was to send each other Bloomberg chat messages making fun of Citi. Their third reaction, after some more serious reflection, was to say "we are keeping the money, see you in court." All of these reactions were pretty reasonable and worked out well for them. What happened? Well, it starts with the fact that some of the term-loan lenders had agreed to the aggressive deal to put in new money and roll their term loans into new, better-secured debt.[1] So they came to Citi and Revlon, handed in their old debt and got back new debt. When they do this, customarily, they get paid accrued interest on their old debt. Citi, for some reason, couldn't handle that sensibly; from the opinion: Given certain technical limitations of Citibank's system for making payments, the most efficient way for Citibank to effect the transaction was to pay interim interest accrued to all lenders that held 2020 Extended Term Loans; paying only the rolling-up entities would have required a "very manual process."

So instead of just paying interim interest to the lenders who were rolling their old loans into new loans, Citi had to pay it to all of the lenders, and Revlon agreed to make an interim interest payment to everyone.[2] So Revlon wired $7.8 million—for an interest payment—to Citi, and Citi got set up to pay it to the lenders:[3] The August 11th roll-up transaction involved five Lenders, all managed by Angelo, Gordon and Co. ("Angelo Gordon"). The Lenders affiliated with Angelo Gordon were exchanging their positions in the 2016 Term Loan for positions in a different Revlon credit facility. Following this exchange, the remaining Lenders would continue to hold a pro rata share of the 2016 Term Loan on a slightly reduced principal balance. As noted above, when a lender rolls up and exchanges a position in one credit facility for another, it is typically paid the accrued interest on the first facility at the time of the exchange. Due to the same technical limitations of Citibank's system ... Revlon agreed to pay accrued interest to all 2016 Term Loan Lenders to effect the Angelo Gordon roll-up transaction — even though the other Lenders were not involved in the roll-up transaction and even though an interim interest payment was not due under the Amended Loan Agreement until August 28, 2020.

But the Angelo Gordon funds were getting taken out of the loan entirely and rolled into the new facility, so their principal also had to be paid off. (Not really—they would get cashed out at par and roll their money into the new facility, without taking out actual cash—but as a bookkeeping matter.) Here is a paragraph that I think you can only read with slowly dawning horror: Citibank's Asset-Based Transitional Finance ("ABTF") team, a subgroup of Citibank's Loan Operations group that is focused on processing and servicing of asset-based loans, was tasked with executing the roll-up transaction on Flexcube, a software application and loan product processing program that the bank uses for initiating and executing wire payments. On Flexcube, the easiest (or perhaps only) way to execute the transaction — to pay the Angelo Gordon Lenders their share of the principal and interim interest owed as of August 11, 2020, and then to reconstitute the 2016 Term Loan with the remaining Lenders — was to enter it in the system as if paying off the loan in its entirety, thereby triggering accrued interest payments to all Lenders, but to direct the principal portion of the payment to a "wash account" — "an internal Citibank account that shows journal entries . . . used for certain Flexcube transactions to account for internal cashless fund entries and . . . to help ensure that money does not leave the bank."

Ah ha ha! Yes! The "easiest (or perhaps only)" way to pay off some lenders but not others was to instruct the software to pay off all the lenders! But tell it only to pretend to pay them! Just send that money to a wash account! This is all fine! Let's read another horrifying paragraph! Because the vast majority of wire transactions processed by Citibank using Flexcube involve the payment of funds to third parties, any payment entered into the system is released as a wire payment unless the maker suppresses the default option. Citibank's internal Fund Sighting Manual provides instructions for suppressing Flexcube's default. When entering a payment, the employee is presented with a menu with several "boxes" that can be "checked" along with an associated field in which an account number can be input. The Fund Sighting Manual explains that, in order to suppress payment of a principal amount, "ALL of the below field[s] must be set to the wash account: FRONT[;] FUND[; and] PRINCIPAL" — meaning that the employee had to check all three of those boxes and input the wash account number into the relevant fields.

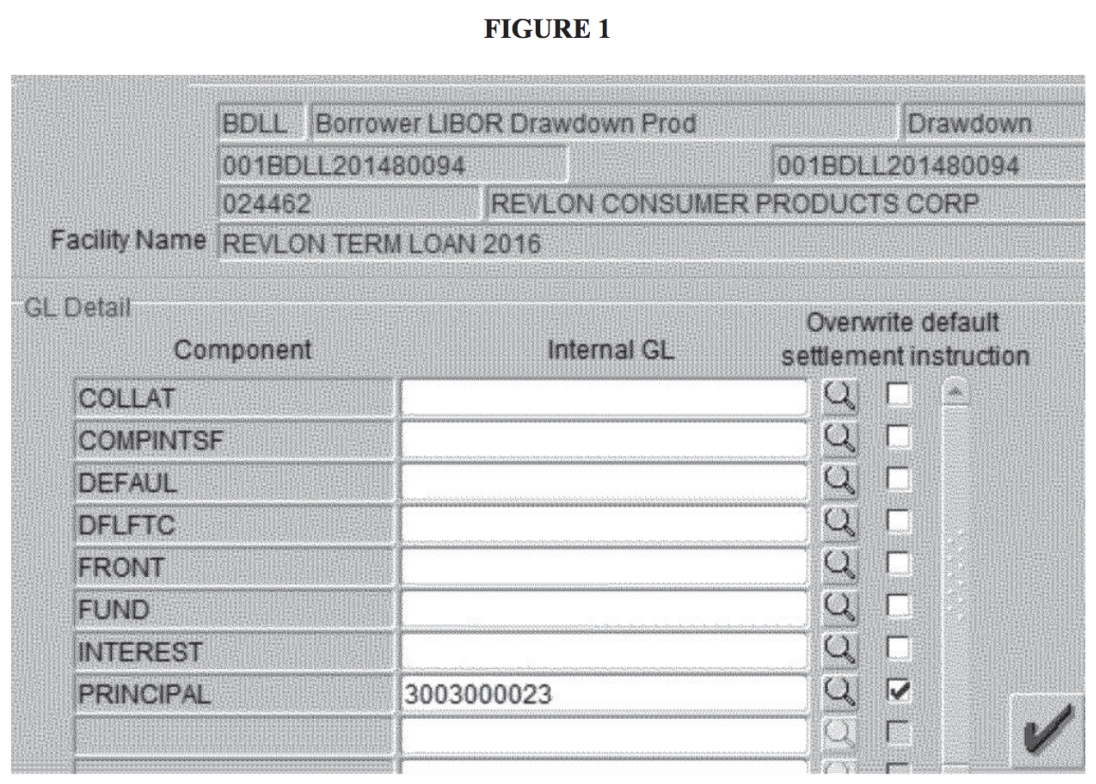

This is just demented stuff. If you want to send out interest payments in cash, but send the principal payment to the wash account, you have to check the box next to "PRINCIPAL" and also the boxes next to "FRONT" and "FUND." "PRINCIPAL" sounds like principal: You are sending the principal to the wash account, sure, right, yes, check that box. "FRONT" and "FUND" sound like nothing. So the Citi operations people messed it up: Notwithstanding these instructions, Ravi, Raj, and Fratta all believed — incorrectly — that the principal could be properly suppressed solely by setting the "PRINCIPAL" field to the wash account. Accordingly, as Ravi built out the transaction between 5:15 and 5:45 p.m. in his role as maker, he checked off only the PRINCIPAL field, neglecting the FRONT and FUND fields. Figure 1, below, "is an accurate image of the Flexcube screen after [Ravi] input the data." At 5:45 p.m., Ravi emailed Raj for approval of the transaction, explaining that "Princip[al] to Wash A[ccount] & Interest to DDA A[ccount]." The "DDA Account" referenced the Demand Deposit Account, which is an operational, external-facing account used by Citibank to collect payments from customers and make transfers to lenders. After reviewing the transaction, Raj believed — incorrectly — that the principal would be sent to the wash account and only the interest payments would be sent out to the Lenders. Raj then emailed Fratta, seeking final approval under the six-eye review process, explaining "NOTE: Principal set to Wash and Interest Notice released to Investors." Fratta, also believing incorrectly that the default instructions were being properly overridden and the principal payment would be directed to the wash account, not to the Lenders, responded to Raj via email, noting, "Looks good, please proceed. Principal is going to wash."

The software gave him a warning, but not a very good one: Raj then proceeded with the final steps to approve the transfers, which prompted a warning on his computer screen — referred to as a "stop sign" — stating: "Account used is Wire Account and Funds will be sent out of the bank. Do you want to continue?" But "[t]he 'stop sign' did not indicate the amount that would be 'sent out of the bank,' or whether it constituted an amount equal to the intended interest payment, an amount equal to the outstanding principal on the loan, or a total of both." Because Raj intended to release "the interim interest payment to [the] [L]enders," he therefore clicked "YES."

Here's Figure 1; it does not particularly explain itself:  See, the "don't actually send the money" box next to "PRINCIPAL" is checked, but that doesn't do anything, you have to check two other boxes to make it not actually send the money. When they discovered the error the next day, their first reaction was not to email the lenders asking for the money back (that was their second reaction); their first reaction was to email tech support to say the software was broken: At 10:26 a.m., Fratta emailed Citibank's technology support group: "Yesterday we processed a payment with Principal to the wash and Interest to be sent to lenders. All details in the front end screens yesterday le[d] us to believe that the payment would be handled in that manner. . . . Screenshots provided below indicating that the wash account . . . is present and boxes checked appropriately for the principal components." Fratta then forwarded the same email to members of his team, with the subject line "Urgent Wash Account Does not Work." He stated: "Flexcube is not working properly, and it will send your payments out the door to lenders/borrowers. The wash account selection is not working. This lead [sic] to ~1BN going out the door in error yesterday for an ABTF Deal, Revlon." ... Over the course of the day, Fratta learned that the principal payments — which were made with Citibank's own money, as Revlon had provided funds only for the interim interest payments to be made in connection with the roll up transaction —were not caused by a technical error, but by human error: the failure to select the FRONT and FUND fields when inputting the default override instructions in Flexcube.

Nope, nope, he was right the first time, this whole setup is a "technical error." Citi's software will only let you pay principal to some lenders if you pretend to pay it to every lender, and it will only let you pretend to pay principal to every lender if you check the "just pretend" box next to "PRINCIPAL" (fine!) and "FUND" (what?) and "FRONT" (what even?). What a terrifying thing. Anyway so, right, clearly it was a mistake, and Citi asked for its money back. It wired about $900 million of mistaken principal payments, and funds that got about $500 million refused to give the money back. "Finders keepers" is not actually a rule of New York law, and in general if you get a mistaken wire transfer you have to give it back. Citi sued, and the funds said, well, we were owed this money, and you sent it to us, so we're going to keep it. The legal doctrine—the exception to the general rule that you have to give back mistaken wire transfers—is called the "discharge-for-value defense": The recipient is allowed to keep the funds if they discharge a valid debt, the recipient made no misrepresentations to induce the payment, and the recipient did not have notice of the mistake. As the New York Court of Appeals explained the exception: "When a beneficiary receives money to which it is entitled and has no knowledge that the money was erroneously wired, the beneficiary should not have to wonder whether it may retain the funds; rather, such a beneficiary should be able to consider the transfer of funds as a final and complete transaction, not subject to revocation."

The leading case is called Banque Worms, which sounds right. When a bank wires someone money by mistake it can say "ugh we've got the banque worms again." Honestly it is a very strange doctrine. Here it makes some rough sense because the lenders had a real argument that Revlon had defaulted on the loan (by doing the aggressive collateral-stripping transaction), so it was immediately due and payable, but that's not actually a requirement of the discharge-for-value defense and isn't really discussed in the opinion.[4] If everything was fine with the Revlon loan, the lenders had no complaints, and Citi accidentally wired them the money, they'd still get to keep it.[5] Much of the dispute in this case is about whether "the recipient[s] did not have notice of the mistake," that is, whether the lenders should have known, or did know, that the wire transfers were a mistake when they got them. They argued that they had no idea anything was wrong, that the payments were the exact amounts they were owed, that they assumed Revlon was intentionally paying down its loan to avoid litigation or do some other weird transaction, and that it didn't cross their mind that Citi had messed up until Citi sent them recall notices the next afternoon. Once Citi did send the recall notices, of course, the lenders knew it was a mistake, and they all sent each other chat messages making fun of Citi. "Not surprisingly," writes Judge Furman, "given the nature and size of the mistake, many of these were quite colorful." He can't resist quoting some funny ones and neither can I: DFREY5: I feel really bad for the person that fat fingered a $900mm erroneous payment. Not a great career move . . . . JRABINOWIT12: certainly looks like they'll be looking for new people for their Ops group DFREY5: How was work today honey? It was ok, except I accidentally sent $900mm out to people who weren't supposed to have it DFREY5: Downside of work from home. maybe the dog hit the keyboard JRABINOWIT12: the song "Had a Bad Day" playing the background

But the judge points out that these chats only happened after the recall notices went out, and "the number and nature of these communications reinforce why the absence of such communications before the Recall Notices is so significant." That is, if the lenders had thought the payments were a mistake when they got them, they would have been unable to resist hopping into a chat room and cracking jokes about Citi, as proven by the fact that when they got the recall notices they did all crack jokes about Citi. The fact that they didn't make any jokes for almost a full day proves that, when they got the payments, they thought they were legit. It is a weird rule that, if you get a payment that you think is legit, and then one minute later you get a notice saying "no sorry this payment was an error," you nonetheless get to keep the payment, but I guess that's the rule. Banque Worms! What a mess. Obviously this is good for the funds who kept the money. It is awkward for the funds who returned the money; they can't ask Citi to send it back to them. They're stuck holding the loan until it matures or defaults; Bloomberg tells me that it's trading at around 42 cents on the dollar. Their clients are going to have questions about their aggressiveness and creativity. Aggressiveness and creativity are kind of the whole ballgame when you are trading distressed debt; the business is about hunting for arcane advantages that you can exploit to get more money than the other guys. In a sense the discharge-for-value exception is an arcane advantage, but in another sense "well they sent us money so we're going to keep it" is the least arcane imaginable thing, and if you don't have that instinct perhaps you were meant for a gentler corner of the financial world. It's awkward for Citigroup and Revlon too. What do they do? Does Revlon owe Citi the $500 million now? Payable in 2023? I mean, presumably, right?[6] Presumably when Citi accidentally paid off Revlon's loan, that wasn't just a gift to Revlon? But neither did it accelerate Revlon's debt? Citi just bought $500 million worth of the term loan at par and has to wait to get paid back? "'If appeals fail, Citi will ultimately step into the shoes of the lenders and own $500 million of that nearly $900 million term loan,' said Philip Brendel, a senior distressed debt analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence." Can it syndicate whatever this is? Sell some of its weird phantom claims on the term loan to distressed-debt funds? Maybe the same funds that just took it for $500 million? Or I suppose Citi and Revlon could cut a deal where Citi gets paid back X cents on the dollar soon and leads some weird new debt-restructuring transaction for Revlon to fund it. That should be easier now. All the aggressive funds are gone. When this all happened, there was a certain amount of commentary to the effect of This Proves Citi Is Too Big To Manage and a Threat to Global Financial Stability. That feels a little overblown to me—meh, now Citi owns $500 million of a mispriced loan to Revlon, it's had bigger problems—but on the other hand, what an absolutely hair-raising description of Citi's software this is. It is all well and good to say that a bank is "too big to manage," but what that means in practice is surely something like this. It means you have to check three boxes to not send out money instead of one, and people forget to check two of them. MorningstarYesterday the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission sued Morningstar Credit Ratings LLC for being too generous when it rated commercial mortgage-backed securities, and it is another software-design horror story, though of an opposite kind. In commercial mortgage-backed securities, CMBS, banks package a bunch of commercial mortgages into a pool and then issue securities—"certificates"—backed by the pool. If mortgages in the pool default, some of the certificates—the junior tranches—will lose money first, while other certificates—the senior tranches—won't lose anything until the junior tranches are completely wiped out. This means that the senior tranches are very safe and can get AAA ratings from ratings firms like Morningstar, which means very conservative and regulated investors can buy them. Much of the game of issuing CMBS, then, is about maximizing the portion of the securities that get high (ideally AAA) ratings. If you pool a bunch of conservative low-loan-to-value loans against a diversified pool of good properties into a CMBS, a lot of the certificates will be AAA; if you pool a bunch of risky loans against garbage, more of the certificates will be BBB or worse. Ratings firms have a natural and well understood conflict of interest. On the one hand, they should try to give things the correct ratings; if you hand them a pool of risky loans against garbage, they should give the securities relatively low ratings (not much AAA), to reflect the actual probability of default and uphold their standards of intellectual honesty and protect innocent investors and so forth. On the other hand, the banks that issue CMBS want good ratings (lots of AAA), and if a ratings firm doesn't give out lots of AAA ratings the banks (who build the CMBS, pick the ratings agencies and pay them) will go somewhere else. Also to be fair investors want lots of AAA ratings; most (not all!) of the time, everyone is happiest if they just all pretend that everything is AAA and the ratings agencies back them up. But this conflict is, again, very well understood, and politicians and regulators hate it, and the SEC monitors the ratings firms to make sure they're not just giving everything AAA ratings. One way to do that is by regulating their ratings models, or at least their disclosure of their models. The ratings firms have to have quantitative models that take inputs—about the cash flows of the buildings in the CMBS pool, etc.—and apply some predictable process to them to decide how much of the pool gets rated AAA, etc. And they have to disclose how those models work. In theory the purpose of this is so that investors can understand what the ratings mean. In practice the purpose is to let the SEC sue ratings firms if they nudge ratings up on an ad hoc basis. The investors don't actually care how the model works or what the ratings mean; they just want to buy AAA-rated stuff with high yields. But once the ratings firm writes down how its model works, if it deviates from the model to please a bank, the SEC can sue it. "You said that you rated CMBS in a principled way based on standard criteria, and instead you just rated everything AAA, so, fraud." From the SEC's press release yesterday: "To increase transparency and guard against conflicts of interest, the federal securities laws require credit rating agencies to disclose how ratings are determined and to have effective internal controls to ensure they adhere to their ratings methodologies," said Daniel Michael, Chief of the SEC Enforcement Division's Complex Financial Instruments Unit. "In this action, the complaint alleges that Morningstar failed on both counts by permitting analysts to make undisclosed adjustments over which Morningstar had no effective internal controls."

Fine. Morningstar had a model for rating CMBS, which it disclosed in documents on its website called "CMBS New-Issue Ratings Opinions" and "CMBS Subordination Model." Here's how the SEC describes it: The first step of Morningstar's rating process was to underwrite a representative sample of the pool of commercial real estate loans that collateralized each CMBS transaction. … Through this underwriting process, Morningstar calculated the expected net cash flow that each commercial property would generate over the life of the loan, along with the value of each property, using a capitalization rate that Morningstar determined. As a result, the key outputs of the underwriting process were the net cash flow and capitalization rate for each loan. The next step of Morningstar's disclosed methodology, as explained in the publicly available CMBS Subordination Model document, was to input each loan's net cash flow and capitalization rate from the underwriting process into Morningstar's Subordination Model, an Excel spreadsheet. The Subordination Model then subjected these values to "defined sets of stresses" to assess the likelihood of loans to default at each rating category. The model's outputs showed the loans' losses under various economic scenarios, expressed as a percentage of the total value of the CMBS certificates being issued. Those percentages were the model-generated subordination levels, or credit enhancement, for the various rating categories.

Intuitively, if severe stress would lead to 23% defaults, then at most 77% of the pool could be AAA-rated, etc. Did you catch the bad words in that passage? The bad words were "an Excel spreadsheet." Morningstar had a ratings model that was subject to careful regulatory scrutiny; Morningstar disclosed how it worked, and investors supposedly relied on that disclosure when they bought CMBS. But the model lived in Microsoft Excel. If you were the Morningstar analyst working on rating a new deal, you copied your last deal into New_Deal.xlsx, and you started typing. You could type lots of things! It's Excel, why not. The SEC complains: Morningstar failed to disclose that a central feature of its Subordination Model allowed analysts to make "loan-specific" adjustments to the disclosed net cash flow and capitalization rate stresses. The adjustments were made in two columns of cells in the Excel spreadsheet … labelled "LOAN SPECIFIC ADJUSTMENTS TO BASE N[ET] C[ASH] F[LOW] STRESS," and the other was labelled "LOAN SPECIFIC ADJUSTMENTS TO BASE CAP RATE STRESS." ... Other than the labels, Morningstar provided its analysts with no criteria or guidance for when or how to employ these adjustments. … Nor did the Subordination Model constrain how large the analyst-employed stress adjustments could be. Even the column labels in the Subordination Model's Excel spreadsheet failed to constrain the use of the adjustments. Morningstar's corporate representative said that analysts could use the adjustments for reasons having nothing to do with a specific loan, such as to nudge a rating produced by the model to align with expectations. Specifically, Morningstar's analysts could use the "loan-specific" stress adjustments when "the aggregate levels that are spit out by the model are either too high or too low relative to other similar transactions we've looked at."

"Even the column labels in the Subordination Model's Excel spreadsheet failed to constrain the use of the adjustments"! Even the column labels! The analysts looked at the columns labeled "do some fudging here, but not in a bad way," and they did some fudging in a bad way, and now the SEC is mad. Even the column labels! Citi's problem is that it had an opaque high-strung bit of software that, if you didn't check exactly the right boxes, would wire hundreds of millions of dollars out of the bank for its own perverse amusement. Morningstar's problem is that it put a highly regulated model in a regular old Excel spreadsheet where analysts could type whatever they wanted, and did. I wonder how many Highly Regulated Excel Spreadsheets there are in the financial industry. Thousands, surely. There you are, doing your job, in your Highly Regulated Excel Spreadsheet. And you get some result you don't like and you say, well, I dunno, I'll just multiply everything by 1.02, that seems fine. And then years later regulators are like, no no no, that was a Highly Regulated Excel Spreadsheet, the column labels were sacrosanct, you can't just type whatever you want there. But of course you could just type whatever you wanted there, because it was in Excel and that's how Excel works. JAAC SPACPerhaps the best reason for a private company to go public by merging with a special-purpose acquisition company, instead of doing a traditional initial public offering, is that each SPAC offers a unique opportunity to go public with a close relationship with an experienced sponsor and a world-class board of directors. A SPAC is not just an undifferentiated tool to access the public markets; it is a true merger, a long-term partnership between the wise pros behind the SPAC and the young geniuses behind the company they acquire. The SPAC doesn't just provide capital but a shared vision and sense of purpose I am sorry I am going to stop typing all this stuff now and get to the punch line: With filings by blank-companies flooding in at a record pace, one new listing captures the spirit of the surge. Just Another Acquisition Corp. filed on Tuesday with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to raise $60 million for an acquisition in an unspecified sector. Thirty trading days into the year, 145 new special purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs, have gone public in the U.S. -- an average of 4.8 per day. At this pace, it will take less than a month for the volume to surpass last year's $83 billion, which is more than the previous decade combined, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Just Another Acquisition will look for targets with a valuation of $300 million to $1.0 billion including debt, according to its filing.

Here's the filing. The ticker will be JAAC. Successful sponsors often go on to sponsor multiple SPACs, and I see a bright future for Yet Another Acquisition Corp., Still Another Acquisition Corp., One More Acquisition Corp., Are You Not Tired of This Yet Acquisition Corp., I Regret My Commitment to This Bit Acquisition Corp., etc. JAAC is targeting middle-market companies, so I guess it will face less competition for hot deals than the unicorn-hunter SPACs. Still, what if it gets involved in a "SPAC-off," where multiple SPACs compete to be the one to take a company public? "We believe the expertise and experience of Mr. Wagenheim in sourcing and creating unique opportunities as well as structuring complex transactions involving creative capital deployment, will make us a partner of choice for potential business combination targets," JAAC says, but its … name … is … Just Another Acquisition Corp.? Like it slumps into the SPAC-off with a heavy sigh and says "well, we are also a SPAC. We're a fine one as SPACs go, I dunno, do what you want." Every SPAC is securities fraudIf a public company's stock goes down, it will get sued for securities fraud. The rules and traditions around initial public offerings are quite strict, due diligence is extensive, and companies try very hard not to say anything in an IPO prospectus that isn't definitely true. The rules around SPAC mergers are a little looser, you can include financial projections, and there is considerably more risk that a SPAC merger will come with some misleading disclosure. SPAC sponsors and private companies love this: It lets them tell the company's story in the best available way, rather than being constrained by arbitrary securities-law rules. On the other hand if you tell a company's story and then the stock goes down, guess what: Waitr Inc. never had the resources of rivals Grubhub Inc. and UberEats. Yet in November 2018 the online food ordering and delivery business went public through a merger with blank-check firm Landcadia Holdings Inc. Landcadia had some powerful names behind it. Tilman Fertitta, a billionaire restaurateur, and Richard Handler, the chief executive officer of Jefferies Financial Group Inc., had raised $250 million in backing for Landcadia so that the special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, could find and take public a promising startup like Waitr. But Waitr turned out to be a disappointment. Its shares plummeted as it lost about 96% of its market value in 2019, down from a high of almost $1 billion. That triggered a class-action lawsuit claiming that Fertitta and Handler misled shareholders about the risks of Waitr's business plan but pushed ahead with announcing their merger two weeks before Landcadia had to return investor money, as it promised. Now, in what could soon be the first ruling of its kind since last year's record number of SPACs went public, a federal judge is weighing to what extent sponsors of these ventures can be held liable for failing to deliver. A hearing is set for March 16 and a ruling could come shortly afterward. Landcadia, Waitr, Fertitta and Handler deny wrongdoing and are urging the judge to dismiss the case.

What is the right model here? Is it like: When a deep-pocketed sponsor takes a SPAC public, if the SPAC goes up the sponsor makes a huge return (typically it gets 20% of the SPAC equity for free, etc.), but if the SPAC goes down the sponsor effectively has to make good investors' losses? Do SPACs come not just with warrants but also with implicit puts, where if the deal goes down too much the sponsor has to pay you back? Is that a good model? Does it make SPACs useful for taking small untested risky companies public at aggressive valuations? Wrong ClubhouseSure whatever: ClubHouse Media Group Inc., a self-described marketing and media firm targeting social media influencers, has surged over 1,000% this year as retail traders mixed the company up with a similarly named app. Beverly Hills, California-based ClubHouse, which changed its name from Tongji Healthcare Group Inc. and promoted its influencer and social media focus starting last month, has drawn some confusion among investors. The company shares a name with the buzzy conversation app known as Clubhouse, which is backed by venture-capital firm Andreessen Horowitz and is not publicly traded.

We talked about this two weeks ago. I mean, we talk about company-name confusion all the time, but we talked about this specific one, ClubHouse/Clubhouse, two weeks ago. At the time, ClubHouse was trading at around $7 a share. It closed yesterday at $27.40. Nothing matters, at all, ever. If you read in Money Stuff "Stock X is up 1,000% this year because people confused it with Thing Y," what does that mean for Stock X's future returns? It's probably bullish, right? (Not investing advice, none of this even counts as "investing," come on.) "People are confused so they might as well keep being confused, or they'll stop being confused and start being confused ironically, making an arch meta joke about stock-ticker confusion by continuing to buy the wrong stock forever." Things happenTexas Power Plants Failed Because They Aren't Dressed for Winter. Wells Fargo Wins Fed's Nod for an Overhaul Plan Tied to Cap. Wells Fargo's $8 Billion Question: How to Slash Costs Without Angering Regulators. Owl Rock-Dyal Merger Mired in $600 Million Sixth Street Dispute. Hedge fund Alden to buy Tribune Publishing in deal valued at $630 million. Pigs Can Be Trained To Play Video Games With Their Snouts, Study Reveals. If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks! [1] When we first talked about this, I wrote that "the weird thing here is that—apparently completely by chance—the accidental payment intersected with a real live debt dispute." That was not quite right; it was not completely by chance. In fact Revlon's aggressive debt deal is what triggered the accidental payment. Karma, or whatever. [2] This is just, like, if the roll-up happens a month after an interest payment date, you pay a month's interest to everyone, and then two months later at the next scheduled interest payment date you only pay two months' interest to the remaining lenders. You pay part of the interest early, but you don't really pay any extra interest. [3] This, and other unattributed quotes, is from yesterday's opinion, and citations are omitted throughout. [4] That is, the opinion does not discuss the lenders' complaints about the collateral-stripping in any great detail. (Though see e.g. pages 25 and 89-93.) It does discuss whether the discharge-for-value doctrine requires that the loan be due and payable, as opposed to just outstanding. (See pages 43-46.) "Citibank argues that to invoke the rule, a creditor must prove that it was 'entitled to the funds at the time of transfer (they must be "due," not just outstanding),'" notes the judge, but he concludes that Citi is wrong. [5] Obviously they'd be less *inclined* to keep it if everything was fine. But if it had traded down without any arguable covenant violations they might be tempted. [6] Or, like, it still owes the $500 million to the hedge funds who won this case, but they are obligated to transfer it to Citi? Something like that? |

Post a Comment