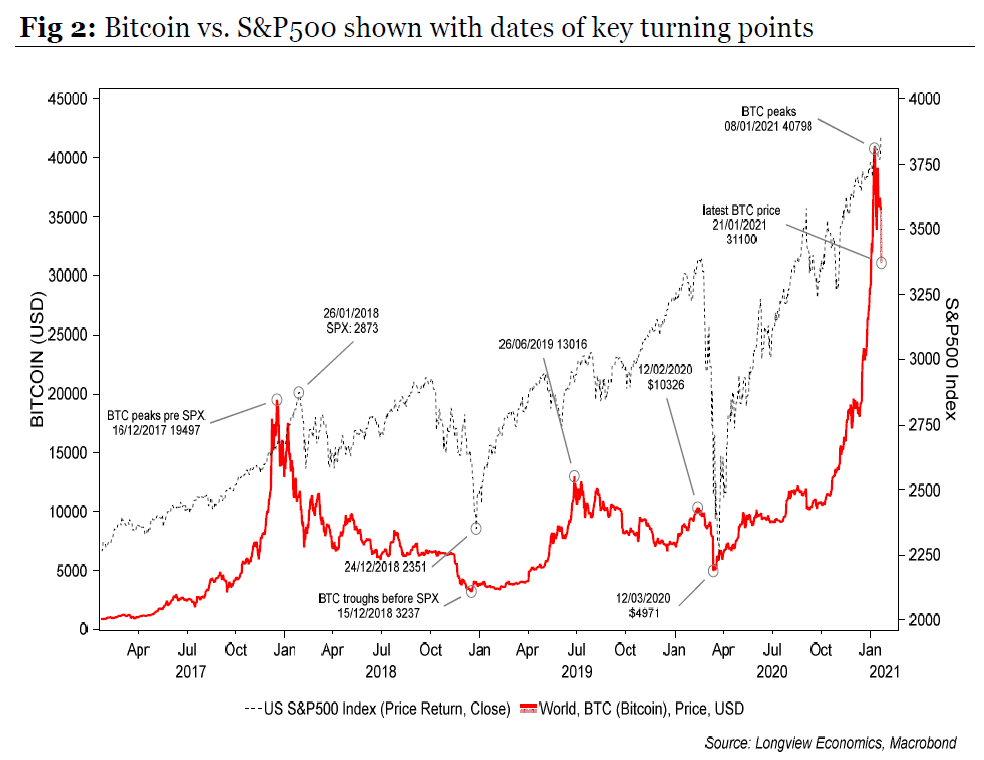

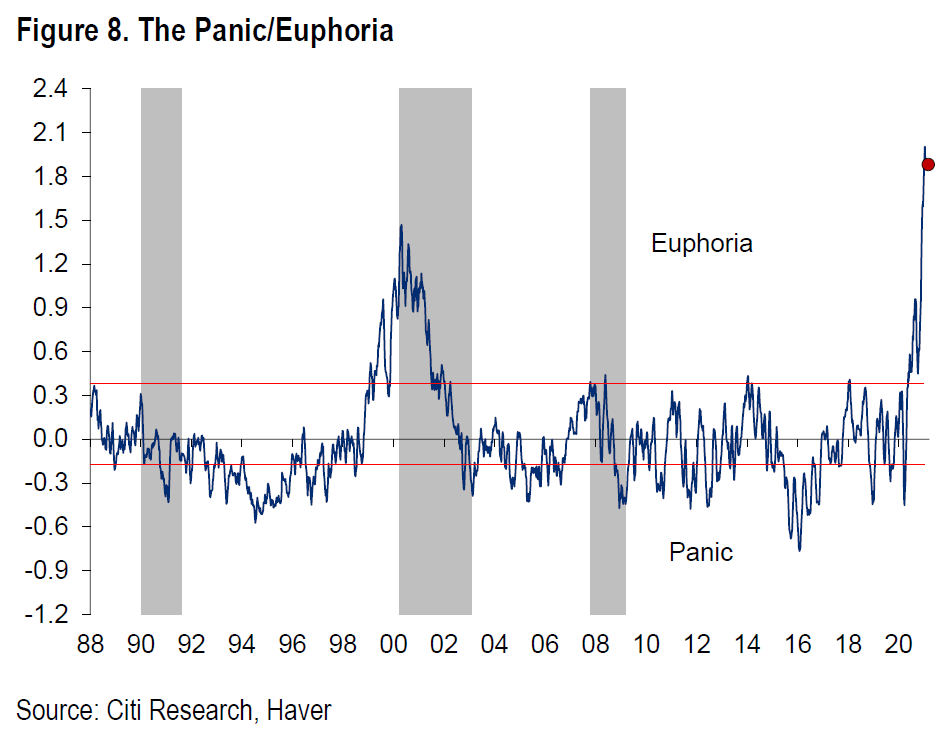

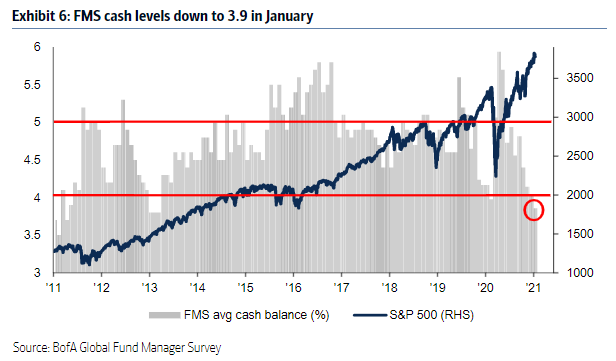

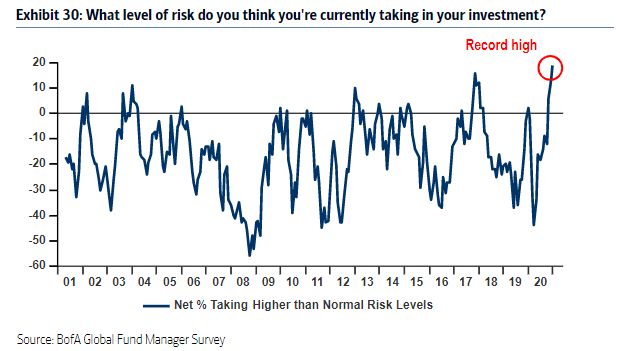

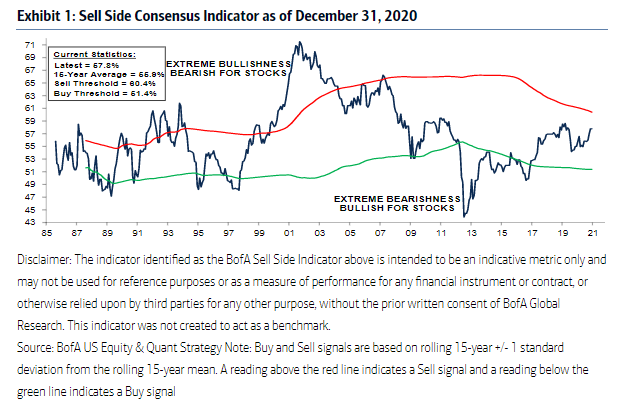

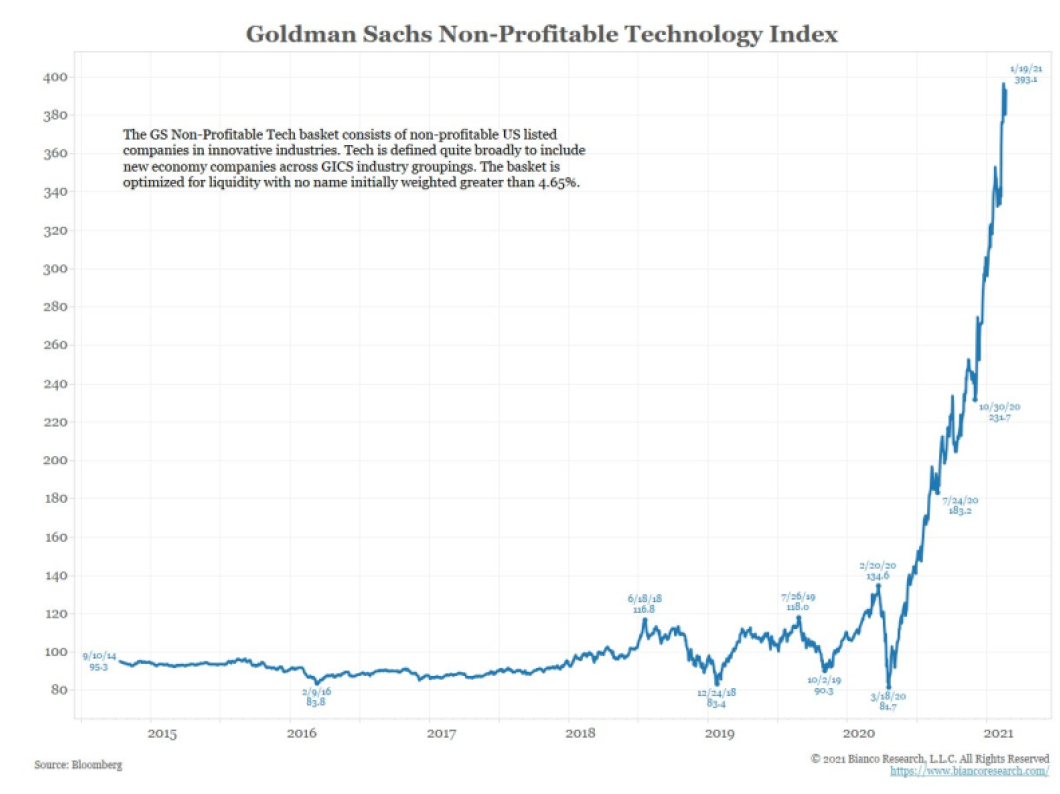

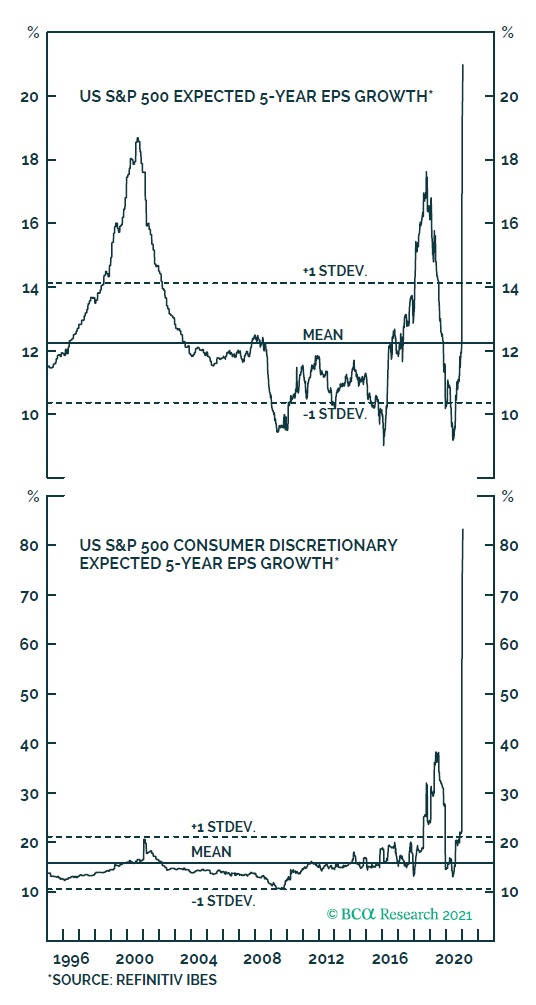

| I'm sorry about this, but I'm forever writing about bubbles. Unfortunately, it's unavoidable. Based on an unscientific survey (my email inbox), interest is its most intense in many years. I've received 210 messages on the subject since the turn of the year. Many are emphatic arguments that we don't in fact have a speculative bubble, but investment debate is being dominated by the question. So it's time for yet another newsletter on bubbles. To recap: Few deny that U.S. stocks look extremely overpriced, or that the historically low levels of bond yields might help to justify these valuations (or less decorously, that central bankers are inflating the bubbles, and there's nothing the rest of us can do about it). Robert Shiller, a Nobel laureate economist, and an expert on bubbles, souped up the debate by arguing that stocks should at least be expected to outperform bonds. After that, Jeremy Grantham, the founder of fund manager GMO, entered with his own argument that U.S. stocks are in a bubble comparable with the South Sea Bubble, the Great Crash of 1929, or the dot-com mania. He based this largely on signs of excessive behavior. All agree that timing the end of a bubble is perilously difficult. What exactly is a bubble, as opposed to an expensive market? Charles Kindleberger, in his classic Manias, Panics, and Crashes, gave the necessary conditions: easy money, and an exciting narrative that will encourage people to invest. A bubble results when valuations become excessive, and investor behavior is dominated solely by attempts to sell to someone else for a higher price, rather than any rational assessment of value. This is what economist Hyman Minsky called the "Ponzi phase." At this point, the slightest interruption to easy money can bring the party to an end. We know we have cheap money. We also have plausible narratives for some technology sectors. Where is the excessive behavior? To start, there is bitcoin, which went ballistic last month. Big swings in bitcoin tend to overlap closely with turning points in equity sentiment, as illustrated here by Longview Economics of London:  Cryptocurrency is a recent phenomenon. For many years, Citigroup Inc.'s chief U.S. equity strategist Tobias Levkovich has been monitoring a "panic/euphoria" index, whose components are as follows: NYSE short interest ratio, margin debt, Nasdaq daily volume as a percentage of NYSE volume, a composite average of Investors Intelligence and the American Association of Individual Investors bullishness data, retail money funds, the put/call ratio, the CRB futures index, gasoline prices, and the ratio of price premiums in puts versus calls. On this measure, euphoria is its highest on record, exceeding even the tech bubble:  For another quantifiable measure of excess, look at BofA Securities Inc.'s gauge of cash held in institutional portfolios. This is the lowest since the firm started measuring it, suggesting fund managers feel little need of a cushion:  BofA has also asked fund managers for the last 20 years whether they consider themselves to be taking a risk. This number has never been higher:  There are various explanations for this, which aren't uniformly negative. Fund managers didn't think they were taking much risk in 2007 and 2008, and that was precisely the problem. At this point, many feel viscerally uncomfortable to be positioned in stocks, but that low returns on bonds and cash leave them no choice. Now if we look at the expectations of sell-side analysts, as regularly polled by BofA Securities, they are higher relative to their long-term rolling mean than they have been since the verge of the global financial crisis. If this isn't indicative of a bubble, it does show that one is very close:  A more specific note of alarm is that non-profitability appears to have become a virtue again, as it was briefly at the top of the tech bubble. This amazing chart was tweeted by my Bloomberg Opinion colleague James Bianco of Bianco Research, and shows the performance of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s index of tech stocks that have yet to turn a profit:  If that isn't terrifying enough, there is also the bizarreness of Tesla Inc. It is now the sixth-largest company in the U.S., and by far the world's largest auto manufacturer by market capitalization, even though many others still sell far more cars. Again, the expectations of sell-side analysts are extreme. The following charts, from Anastasios Avgeriou of BCA Research Inc., show the change in expectations for five-year growth in earnings per share for the S&P 500 and the consumer discretionary sector since Tesla was admitted last month:  As Avgeriou says: Drilling deeper beneath the surface into the consumer discretionary sector is revealing. Tesla's inclusion pushed the sector's 5-year forward profit growth estimates to 83%. To put this in perspective it translates into consumer discretionary profits increasing 20 fold in the next 5 years; no, this is not a typo. Assuming that stock prices follow profits as it typically transpires, then prices will have to rise by a similar amount.

The addition of Yahoo Inc. had a similar impact in 1999, although nowhere near as extreme. Amazon.com Inc., included in 2005, had barely any impact. Tesla might turn out to be a great investment. But its addition to the index, on its own, was enough to render Wall Street's estimates for five-year earnings growth more optimistic than they had ever been. Surely this is crazy. Beyond the data, the weight of anecdotes points to some kind of madness at the market's edge. Peter Atwater of Financial Insyghts has quite a collection. Look for example at the cult of personality building around Cathie Wood, who runs Ark Investment Management, which has enjoyed phenomenal success in the last year. There is now such a thing as Cathie Wood merch, out there on the internet. Beyond Bitcoin and Tesla, there is the frightening story of GameStop Corp. Small investors coordinating in a Reddit discussion group attacked Citron Research after it recommended shorting the gaming company, both buying the stock and hacking Citron's Twitter account. This isn't the way free markets are supposed to work. As Atwater puts it: Maybe it is just me, but it feels like this may be one flash mob too many. The crowd's hubris has become as extreme as the crowd's position in GameStop shares. It may not be today, but when GameStop peaks watch out. With stock prices soaring, and the mad Reddit crowd enriching the bank accounts of corporate shareholders and other investors, no one is complaining as the mob moves from one target to the next. When prices begin to turn down broadly, though, it would not be at all surprising to see sentiment reverse, with institutional investors and corporate insiders demanding that Reddit shut down its pump and dump subreddits much like the crowd called for Twitter to suspend President Trump's account after the Capitol attack. Everything is fun and GameStop until somebody gets hurt – and in today's volatile culture, the means of silencing opponents is now clear – you go after the platforms first.

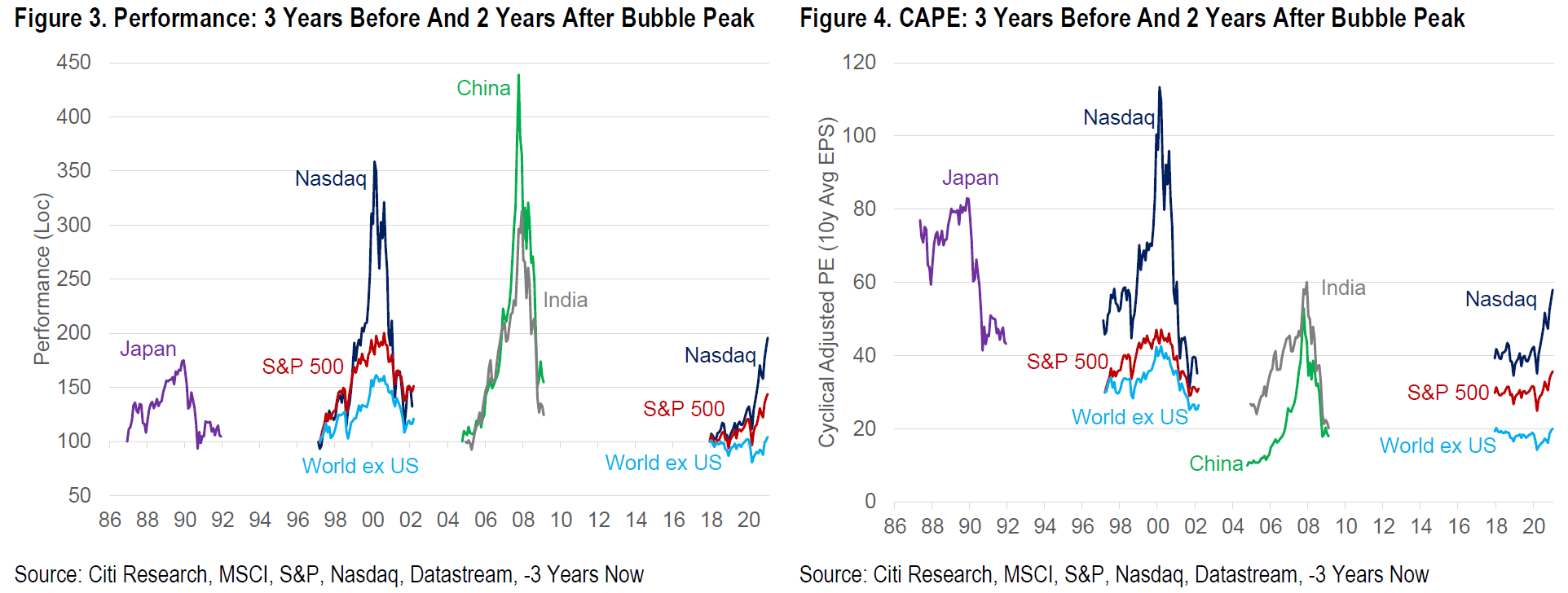

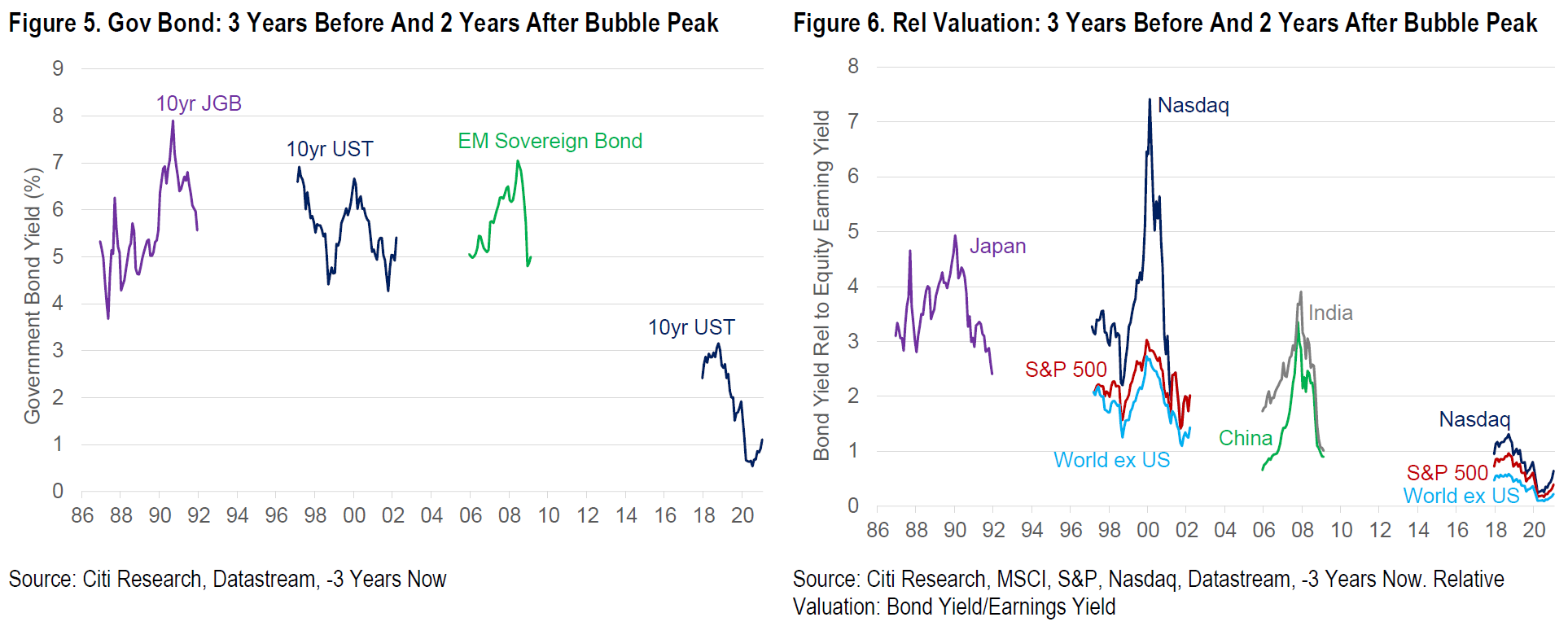

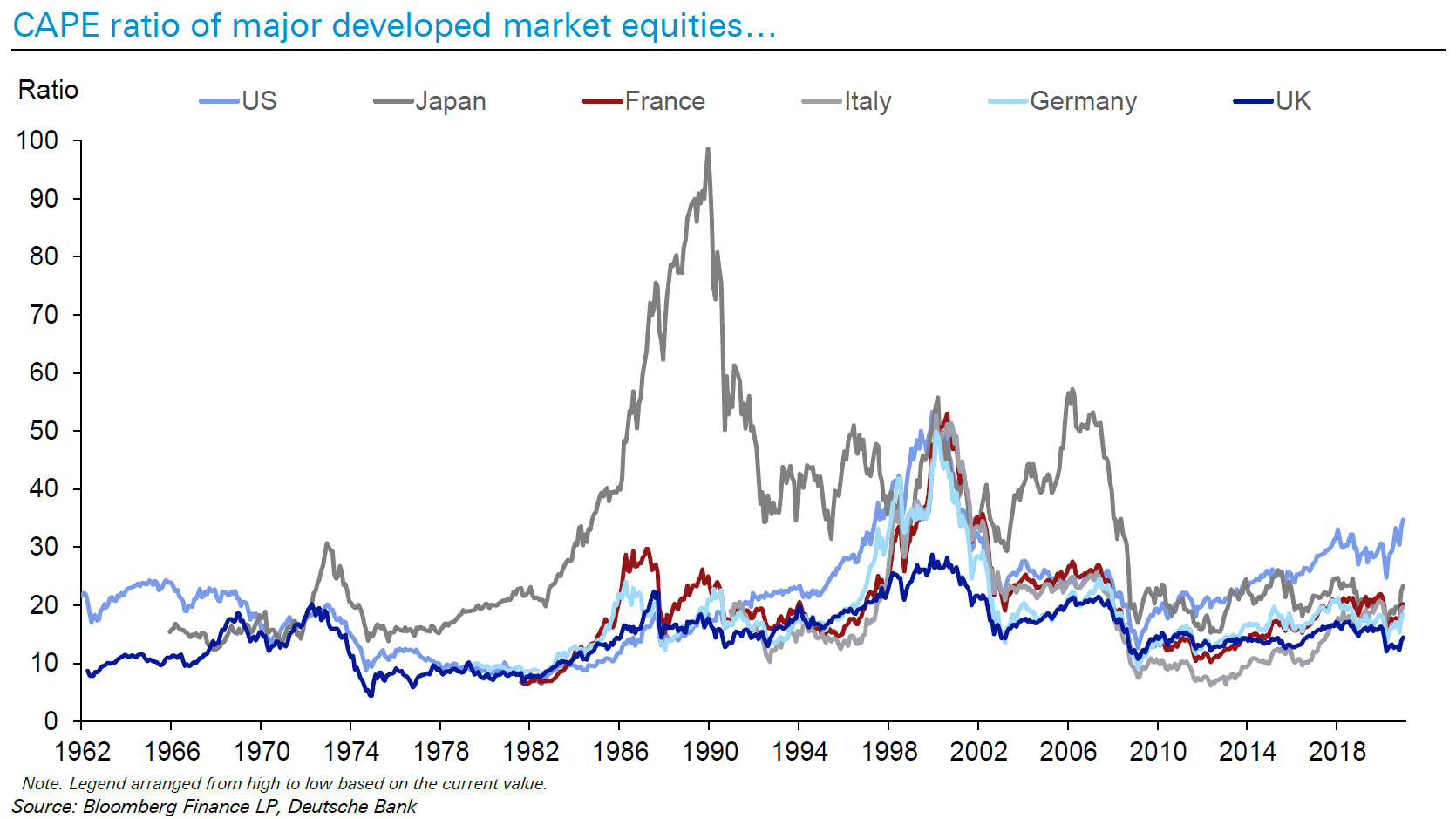

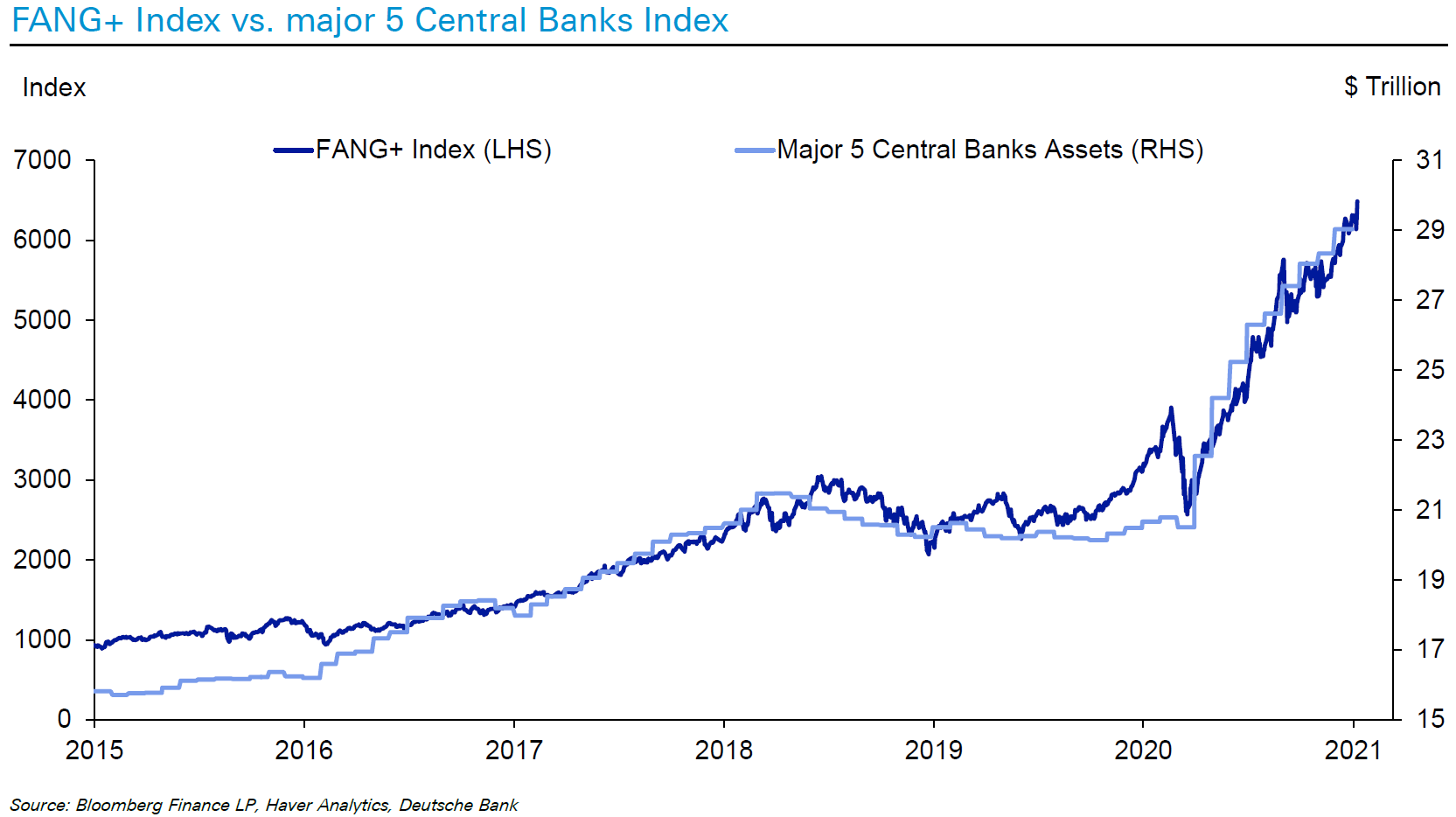

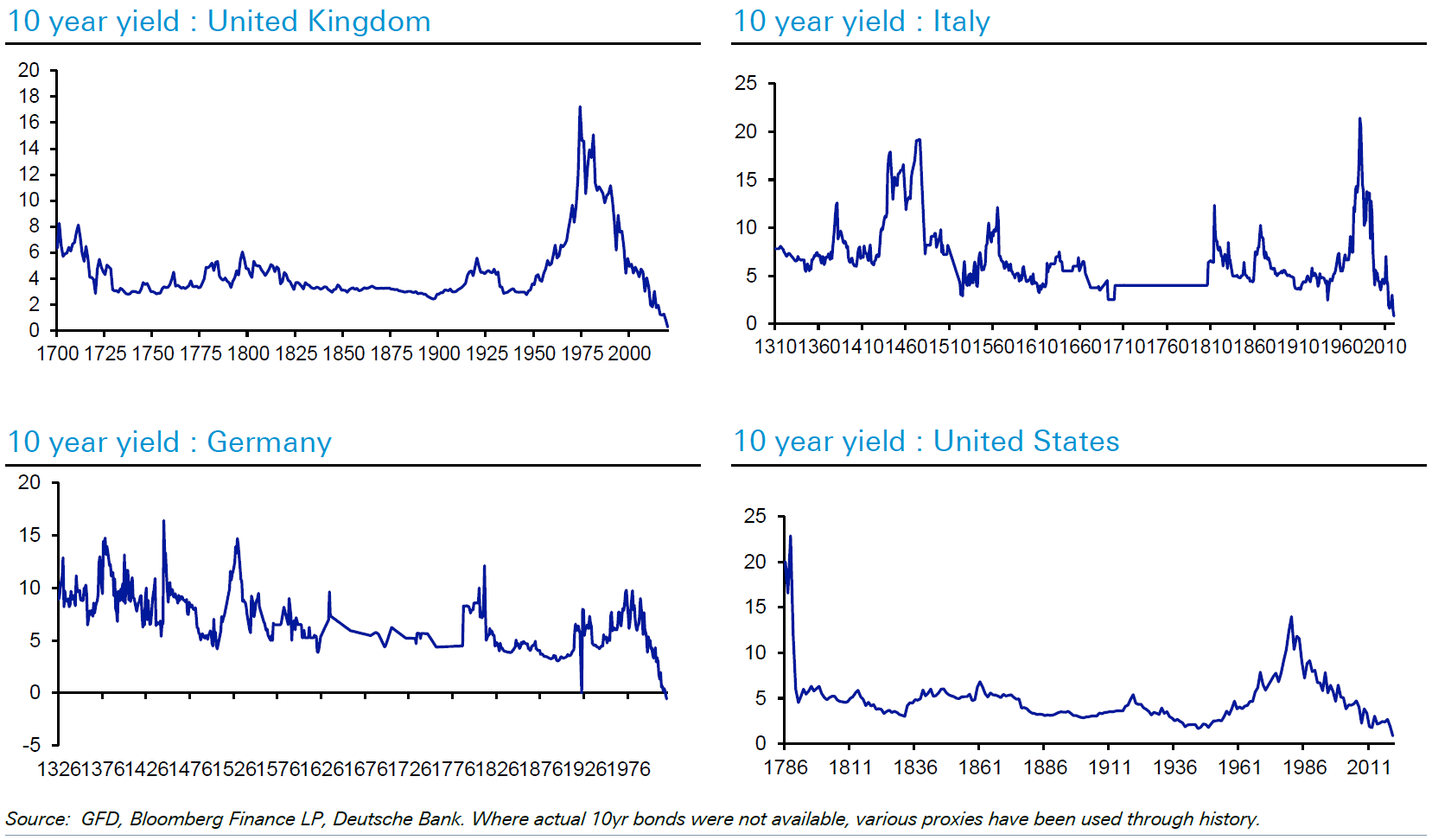

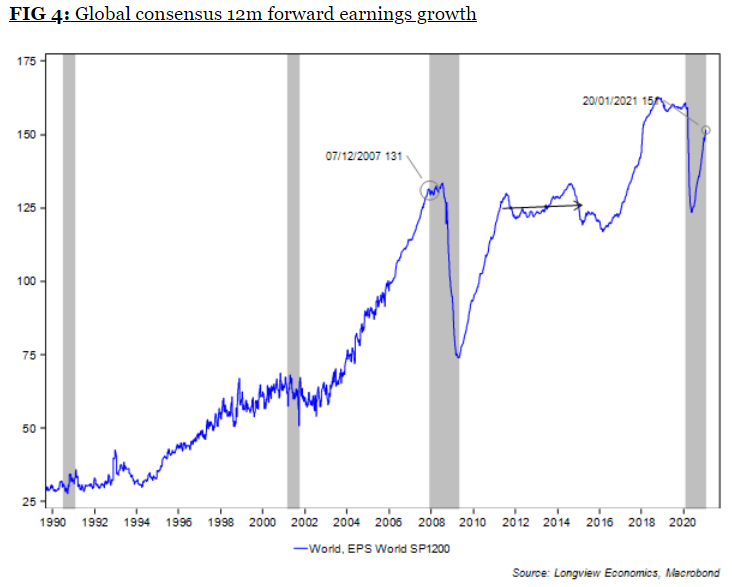

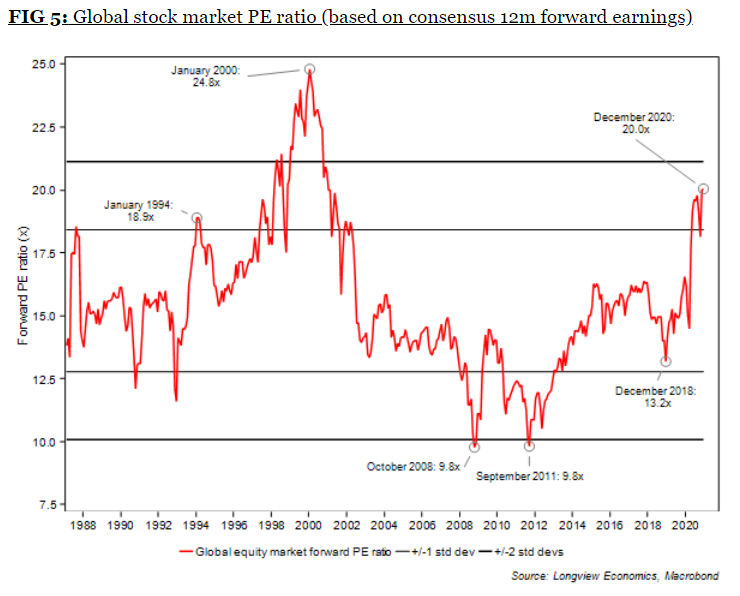

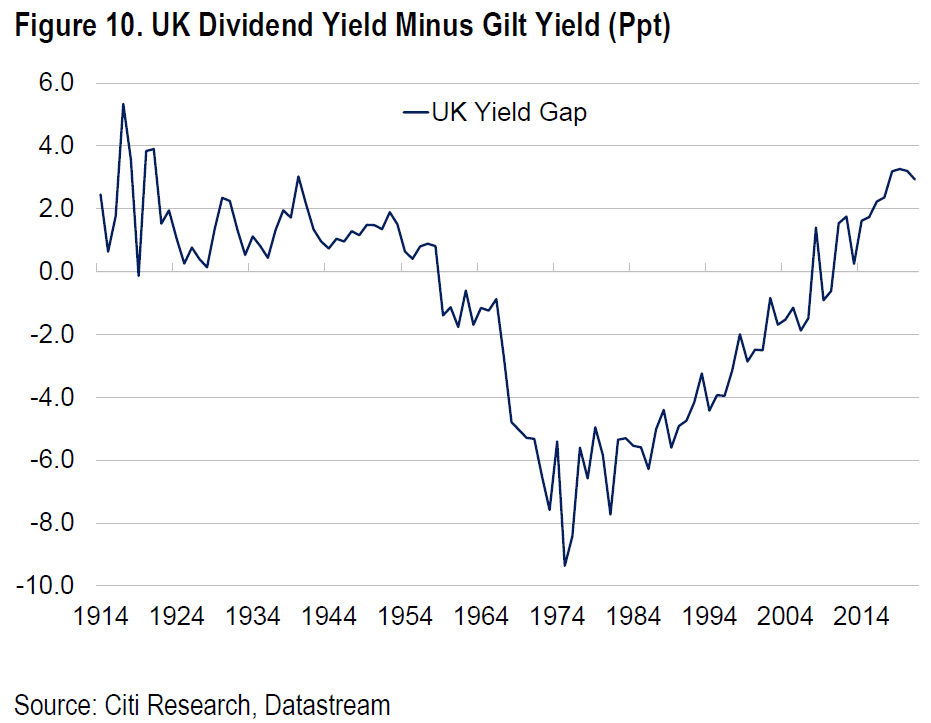

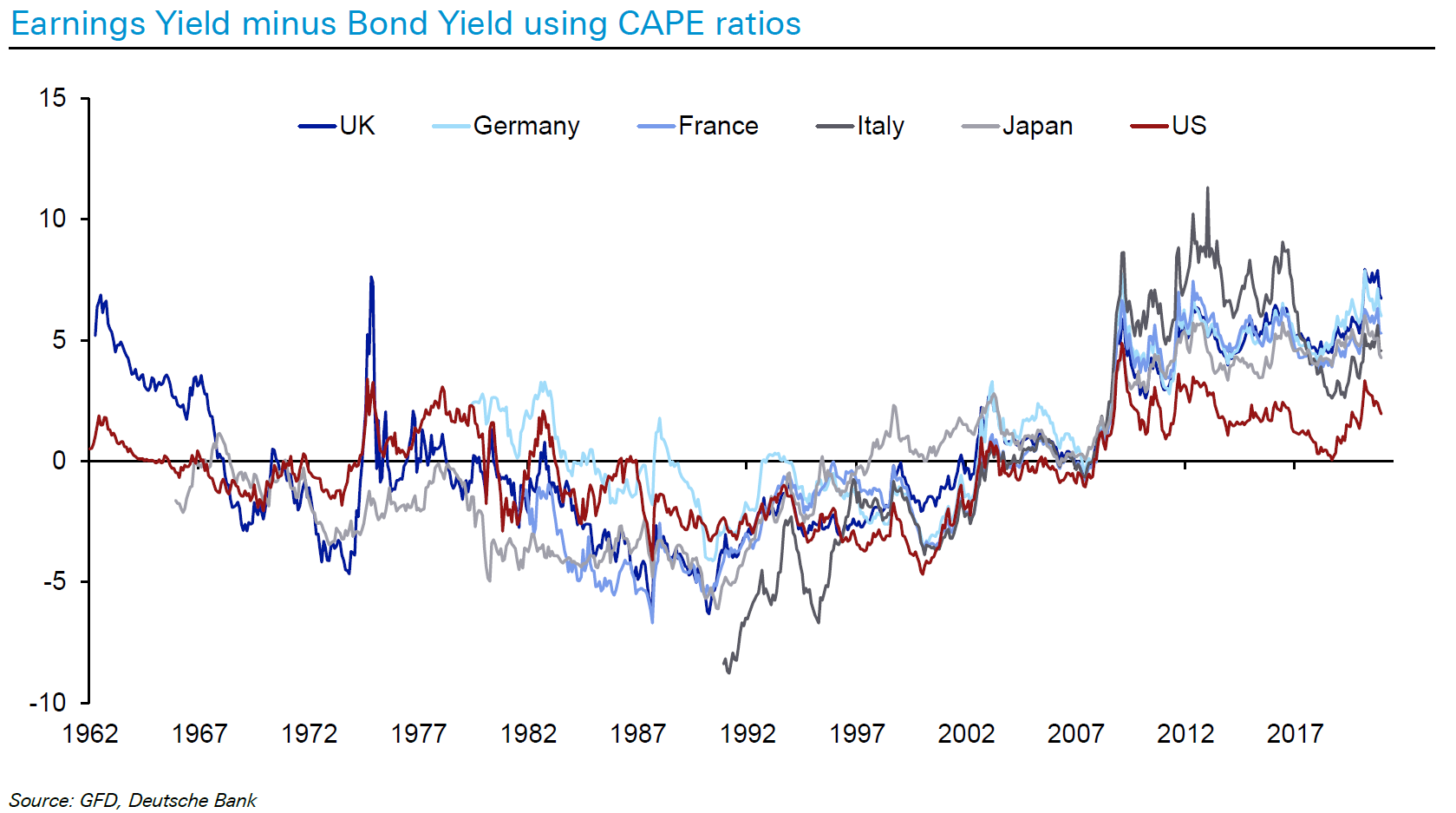

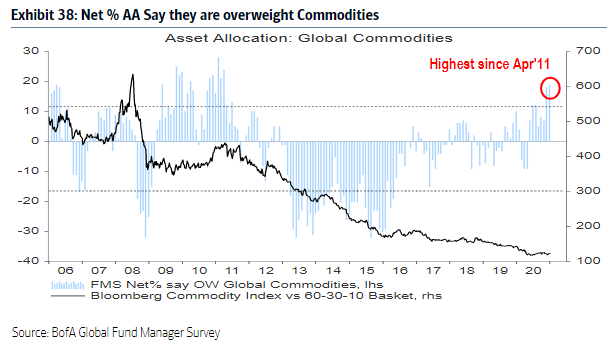

Value in the Eye of the BondholderA true bubble also requires excessive valuations. On a global basis, it is hard to see that they are present. The following charts show an exercise by Rob Buckland, Citi's chief global equity strategist, looking at price performance and then valuation in the three years before previous great bubbles. On this basis, Nasdaq looks overvalued on a scale with the bubble in China that popped in 2007, but far less so than other major bubbles. Meanwhile, the world outside the U.S. doesn't appear to be in a bubble at all:  Now, Buckland brings bonds into the picture. The graph on the right shows 10-year yields around the peak of previous famous bubbles; the graph on the left shows equity valuations relative to bonds. On this basis, we aren't in a bubble at all.  At this point, it is easy to start chasing your tail. Cheap money is generally a pre-condition for a bubble and, according to Kindleberger, its removal is almost universally the catalyst for a collapse. But previous bubbles have generally been about other things as well. This one is almost entirely a function of the historically cheap price of money. Even the great tech bubble was just that. As this chart of cyclically adjusted P/Es going back to 1962 shows, if we look at the U.S. market as a whole, it doesn't appear to be in a bubble now, and looked no more over-hyped than many others at the turn of the century. Meanwhile, Japan looks to have had a bubble on a different scale from anything seen before or since:  So despite the presence of bizarre behavior, it is possible to argue that this is a bubble restricted to U.S. technology, and reliant on historically cheap money. In the wake of the GFC, charts comparing the S&P 500 to the Federal Reserve's balance sheet were popular. Now the Fed's magic appears to apply only to the internet giants in the NYSE Fang+ index:  As for bonds, it is hard to say that anyone is madly speculative about them. But yields really are historically low. The following charts from Deutsche Bank AG's Jim Reid are built on quite a lot of financial archaeology, and speak for themselves. It takes a lot to believe that interest rates can stay this low indefinitely:  The scales for Italy and Germany do indeed go all the way back to the 1300s. If stocks' valuations are dependent on bond yields staying this low, that isn't encouraging. The signs for global stocks as a whole are disquieting. Longview Economics here shows forward earnings for global stocks. Growth since the 2008 peak has been tiny, and derived almost entirely from the one-off boost administered by the Trump corporate tax cut at the end of 2017:  Global stock multiples show a serious overvaluation, although short of the early 2000 extreme:  So something outside the U.S. won't automatically protect you if the American stock market goes pop. If there is one market that looks cheap, it is the U.K. Citi shows that British dividend yields are higher relative to gilt yields than at any time since the war:  Reid of Deutsche Bank expands the exercise slightly, to look at the other major western European economies and Japan, as well as the U.S., comparing the cyclically adjusted price-earnings yield to bond yields. On this basis, the U.S. is by far the least appetizing, and the U.K. the most attractive, closely followed by Germany.  The sectoral composition of U.K. indexes confirms the picture. The FTSE-100 index is dominated by banks, oil companies, miners and multinationals, and has virtually no tech. It is an almost perfect list of the kind of company that has been out of favor. As BofA's fund manager survey shows, commodities are popular again:  Brexit is virtually certain to bring economic costs. But while these are real and significant, they can easily be exaggerated, and the extreme negativity in the behavior of the British currency and stock market suggests those costs are well priced in. Survival TipsThree brief tips: 1) Try to maintain quality control in these difficult times. The eagle-eyed among you noticed we didn't publish a Points of Return last Friday. These things can happen — after a difficult day, I didn't have to time to say anything worth saying. My apologies. 2) Don't forget the next Bloomberg book club, which will culminate in a live blog on the terminal on Wednesday, Feb. 10, at 11 a.m. EST (4 p.m. GMT). We will be discussing The Great Demographic Reversal with Manoj Pradhan, co-author of the book with by Charles Goodhart. Send points and questions to authersnotes@bloomberg.net. 3) I have been sent some more "one-hit wonders." I wonder how I missed them. Try Phyllis Nelson, Strawberry Switchblade, Clout, M, or Babylon Zoo. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment