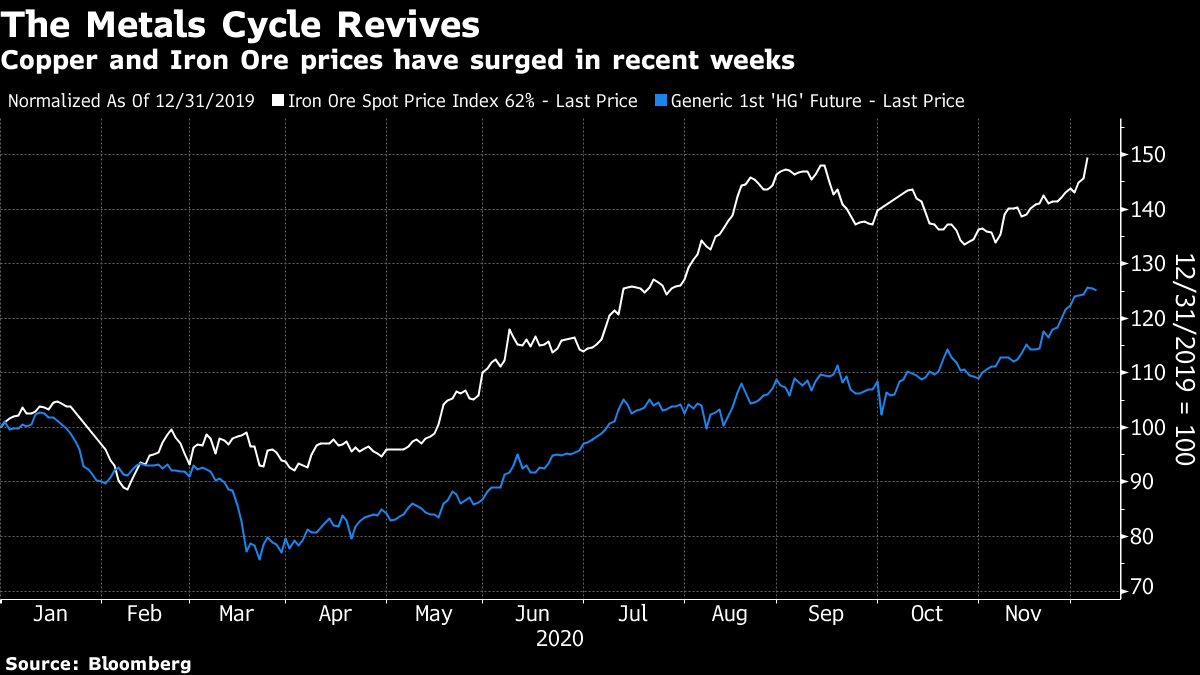

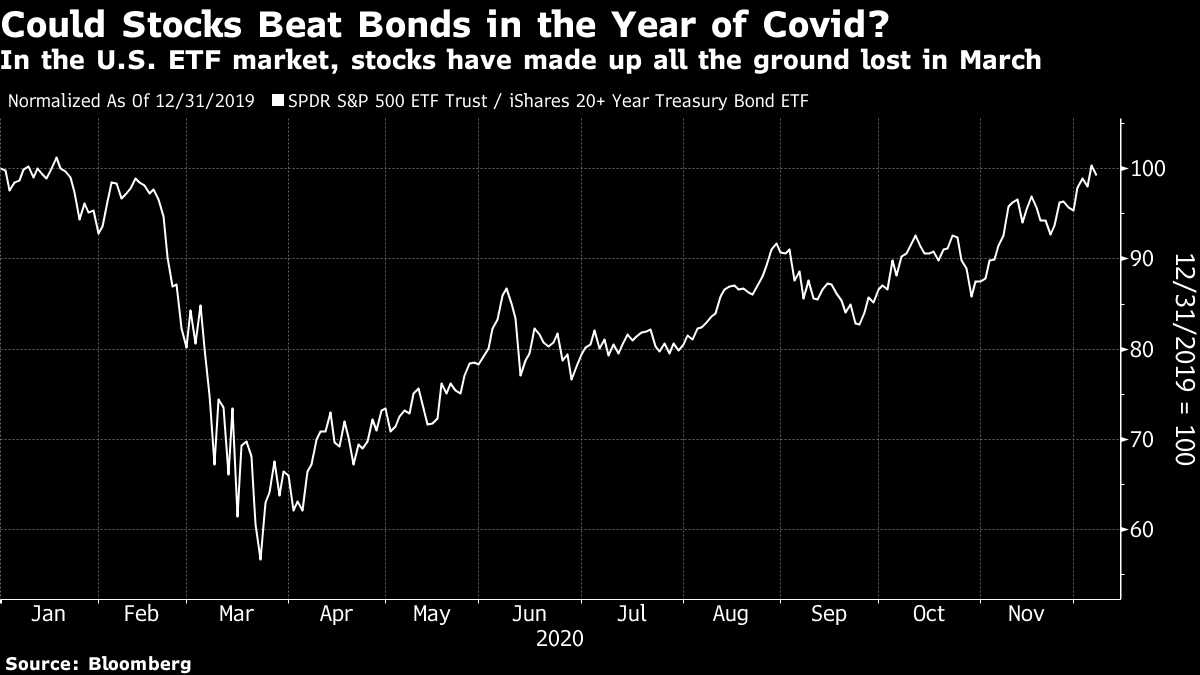

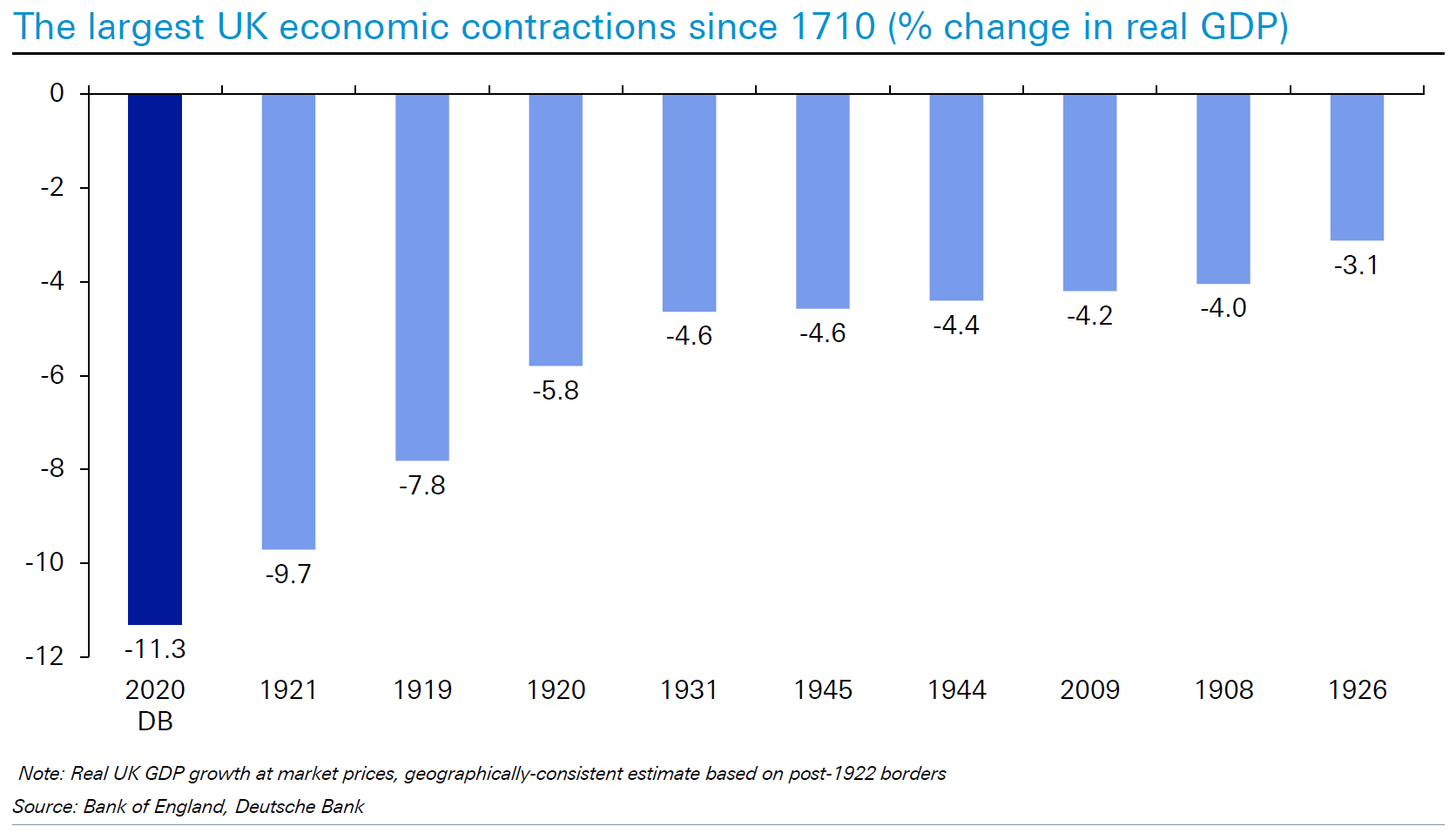

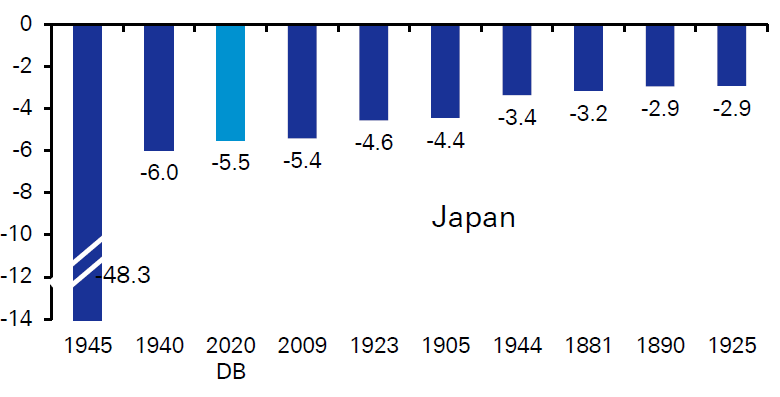

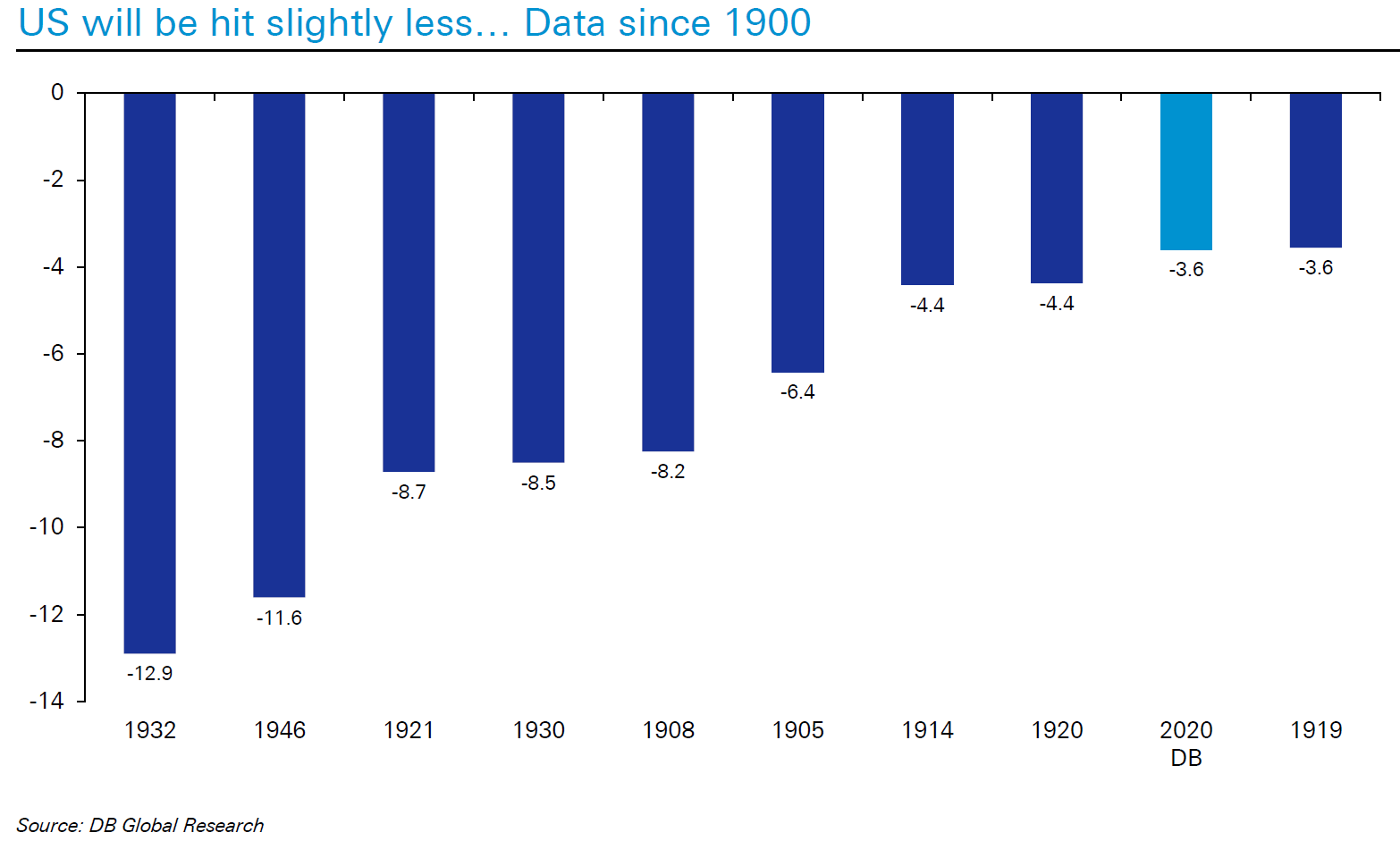

A Clear StoryBlanking out the noise from American and European politics, and the ever more dramatic news about the fight against the pandemic, the story the markets tell about the last few weeks is quite clear. We are in the presence of a classic cyclical recovery. Exhibit a) is the performance of South Korean and Taiwanese stocks. The two great industrial exporters of North Asia, both of which benefit from their place in China's slipstream, are leading all others for the year. South Korea's Kospi index, in particular, has taken off in the last few weeks:  For another tell-tale symptom, look at industrial metals. Iron ore, according to its most popular Chinese benchmark, is up 50% this year. Copper is at a seven-year high and has gained almost 30%:  Another vintage measure of the strength of the economic cycle is the health of the transportation sector. Across the developed world, transport stocks are not only up comfortably for the year, but they have now overtaken the market:  Within the U.S., the dramatic collapse of stocks compared to bonds has almost completely reversed. Central bank intervention to boost the price of bonds has doubtless been crucial to the recovery of the stock market, and of the economy as a whole. Now it has triggered a strong enough response for the S&P 500 to be outpacing the performance of long-dated Treasury bonds for the year:  Strip out all the worries about the coronavirus (most of which are thoroughly justified), and you are left with a basic picture of an economy that slowed down earlier this year, and is now in the process of roaring back. That is obviously good news. It is also remarkable, because we are beginning to get a handle on just how drastic the economic contraction spurred by the virus has been. The following charts come from Jim Reid, investment strategist at Deutsche Bank AG and an indefatigable financial historian. Data for the U.K. go back three centuries and, remarkably, this year's economic contraction in real GDP was the worst ever. The next three worst years, 1919, 1929 and 1921, came wholly uncoincidentally in the slipstream of the First World War and the Spanish flu pandemic:  Disappointingly, none of the economic horrors that afflicted the U.K. in my youth even made the top 10, so I will have to abandon the Monty Python Four Yorkshiremen routine. Data for Japan only go back to the beginning of the last century. The numbers also show what we might have expected, that nothing that has happened to the rest of the world this year remotely compares to what happened to Japan in 1945. That said, apart from the year of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 2020 was the second-worst economic contraction on record in Japan, even though the country was relatively unscathed by the virus:  As for the U.S., by Deutsche estimates this will be only the ninth-worst year for economic growth since the beginning of the last century — although surprisingly the Covid-19 shock did more damage than was inflicted in any single year by the oil shocks of the 1970s:  What is unfolding, then, is a remarkable rebound from a historically serious economic hit. We should all be happy to take this news, and put up with the corollary. As stock markets around the world are actually up in such a year, it is obvious that they have borrowed returns from the future. That is fine; it's what stock markets are supposed to do. But it means that we should moderate expectations for the next few years. As I've commented recently, cyclically adjusted earnings multiples are very high in the U.S. They can reduce via higher earnings in future (which seem to be close to a given), in some combination with lower prices (which are a distinct possibility). Some combination of bullishness about the economy and earnings, and at least relative bearishness about the price of risk assets, permeates the 2021 outlooks now doing the rounds. One way of putting what is coming is from Michael Howell of Crossborder Capital Ltd. in London: We have argued persistently since the COVID Crisis broke last February that the World economy would enjoy a 'V'-shaped recovery. This prediction recognised the whopping liquidity injections made by policy-makers and made use of the simple adage that "… all money that is anywhere, must be somewhere." In short, money flows. With Global Liquidity jumping by some US$20 trillion in 2020, or some 25% of World GDP, there is a lot to spend... Consider that following the 1930s Depression, it took roughly a decade to retain previous economic heights. After the 2008/9 GFC, the World economy clambered back after around two years. But it seems from latest data that it has taken barely six months to recover from the COVID Crisis!

The problem is that money is being used to buy things in the real economy, it isn't being used to pump up the price of stocks: the stark warning from history is that "… strong economies do not have strong financial markets." In other words, if money is being spent in the (virtual) high street, it is not being invested in stocks. Our bullishness about economies forces us to become bearish about stocks. Think of the economy as having two monetary circuits: (1) financial assets and (2) real goods and services. There are feedbacks between both, but essentially money moves sequentially from credit suppliers (e.g. Central Banks) first into the financial circuit and from there into the real economy circuit. The transmission time between these two circuits typically varies from between around six to as long as 20 months. Money tends to move faster into real business activity once it has built up in retail bank accounts, like now, whereas if it is largely wholesale money (as post-2008/9 GFC), it will stick closer to financial assets for longer.

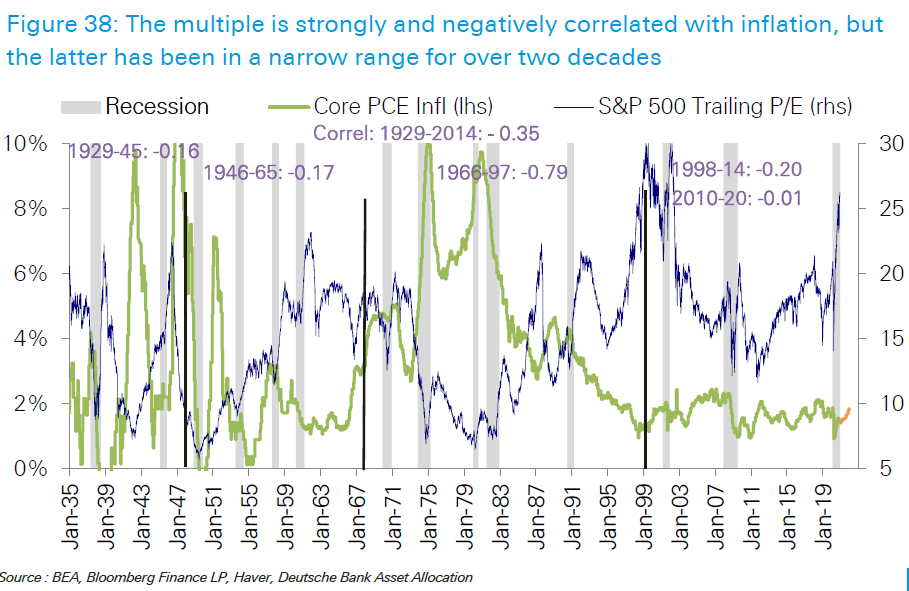

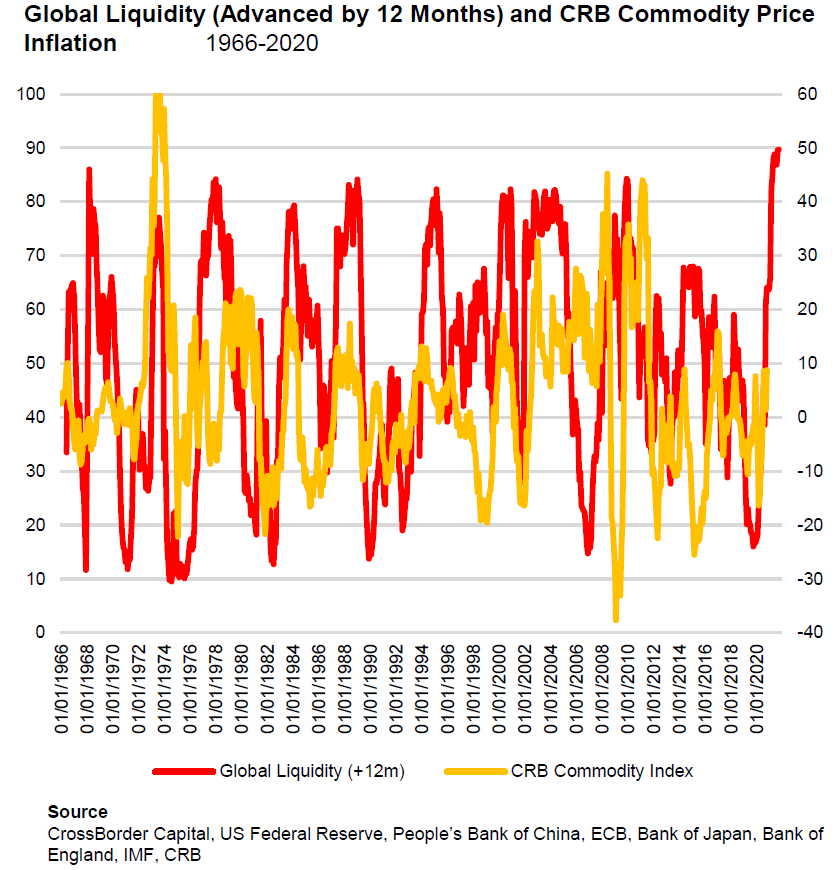

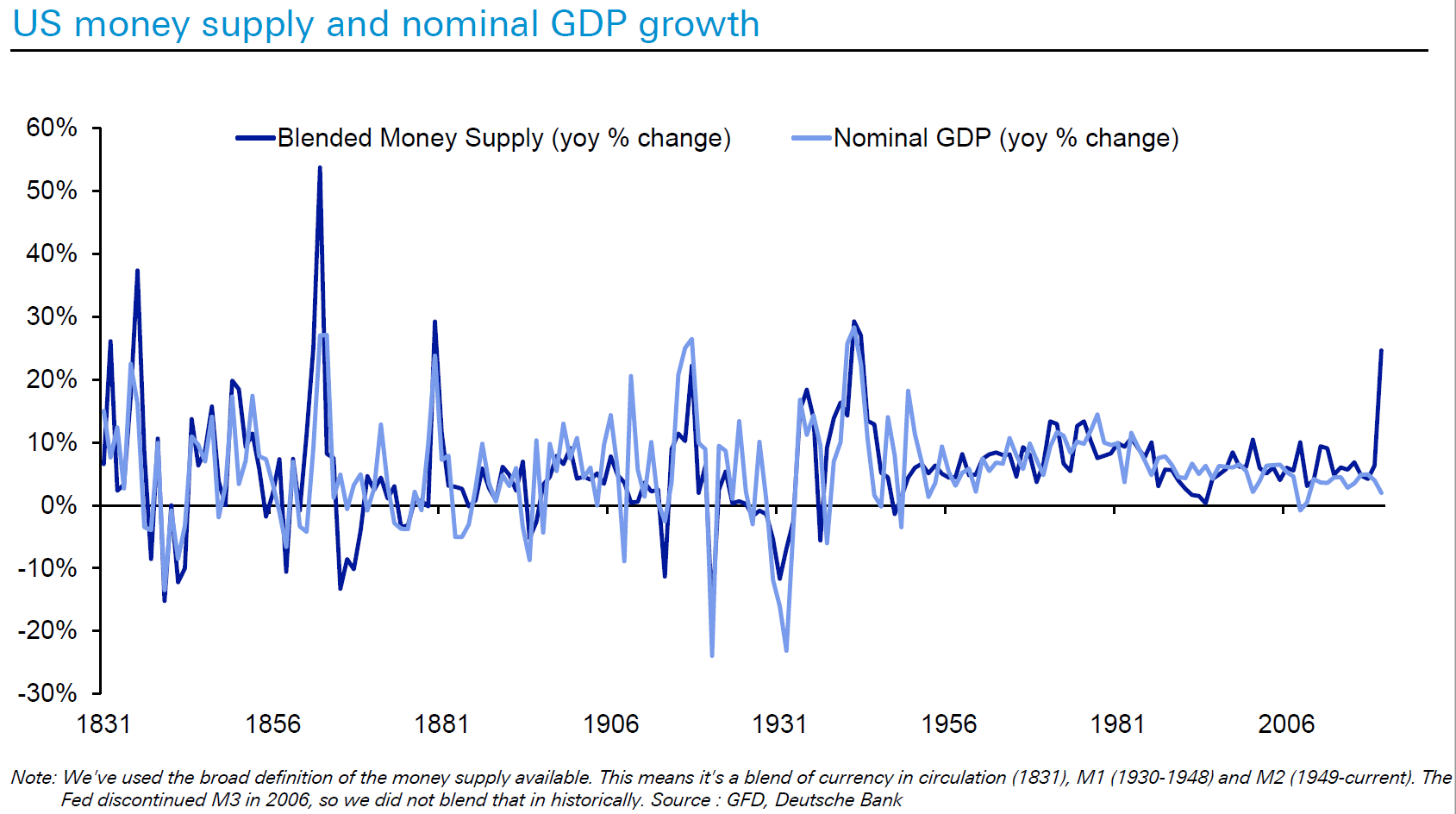

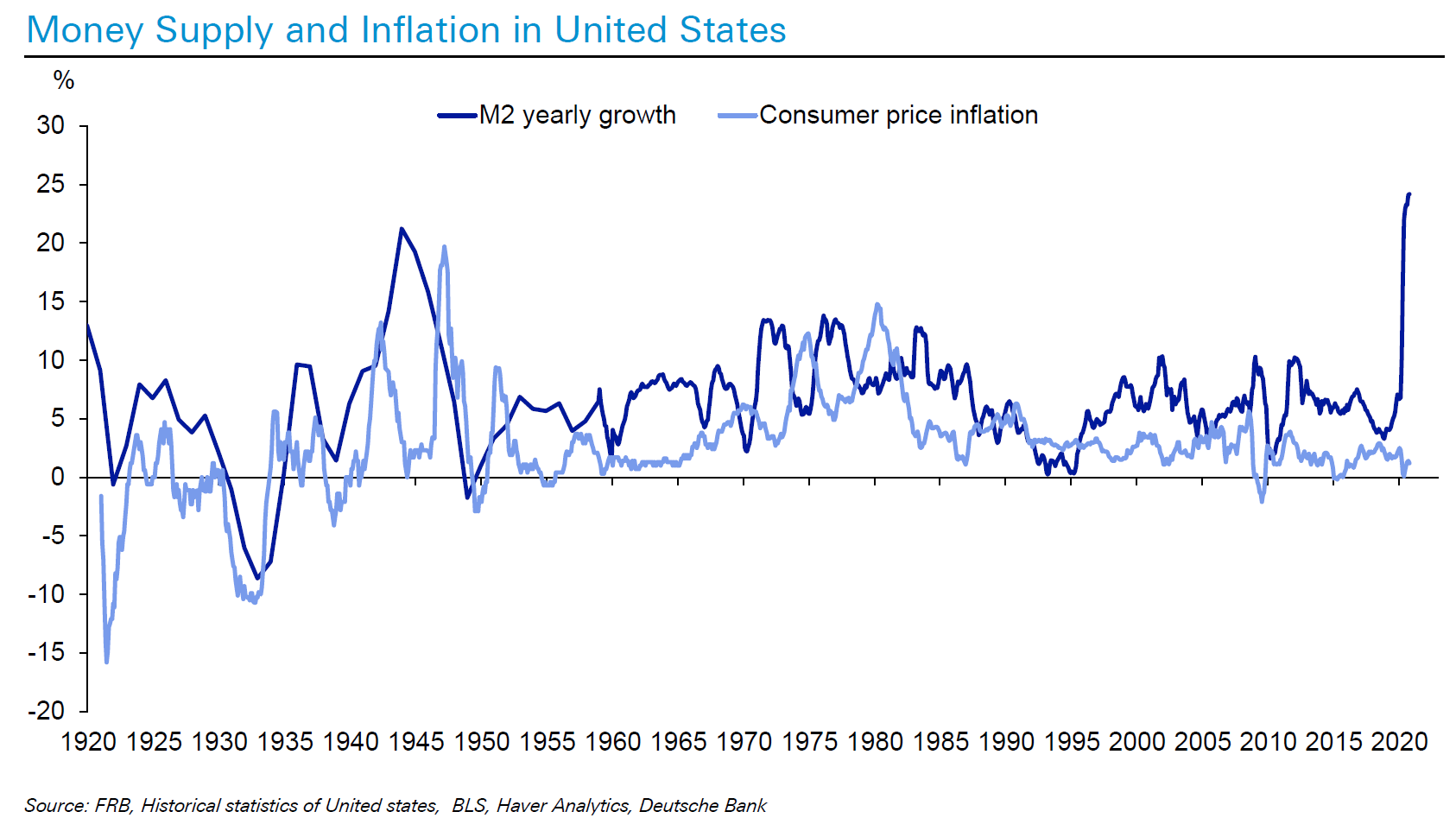

Note that this is still extremely good news if you are worried about inequality, lack of social cohesion, and the risk of populist revolt. If this latest dose of easy money is actually going to lead to real people buying stuff that they need, these risks are much reduced. In more technical language, we can expect earnings to grow next year, after a horrific contraction this year; but we can also expect earnings multiples to decline from their current historic highs. For several decades after the war, the "Rule of 20" was one of the most well practiced tenets of investing. Subtract the current rate of inflation from 20, the rule went, and that was the multiple you should be paying for stocks. It failed to hold up once inflation reached 20%, as it did in some Western countries, and it has fallen by the wayside now with consumer-price gains seemingly permanently trapped below 2%. But there are good reasons for an inverse relationship between inflation and earnings multiples. The link is clear over history, as this chart from Deutsche's Bankim Chadha shows:  If the green line, for inflation, were ever to start rising again, then the blue line, for earnings multiples, might be expected to decline. Will we see inflation again? With liquidity coursing into the real economy, and markets yelling that a China-led cyclical recovery is under way, there should be a chance. As this Crossborder Capital chart shows, a spurt of liquidity on the scale we have just seen can be expected to lead to a sharp further increase in commodity prices (which would be directly inflationary):  It can also be expected to cause dramatic economic reflation. This chart comparing money supply and nominal GDP growth in the U.S., is from Reid of Deutsche:  Money supply expansion like this without economic growth to match is very unusual. Meanwhile, money supply growth on this scale also tends, without quite such a tight relationship, to lead to inflation:  Yes, after the desperate money-printing to get through the global financial crisis in 2008, many braced for a recurrence of inflation that never came. But look at how much greater the increase in money supply is this time. Stepping back, and trying to pretend that we have no knowledge of the pandemic or politics, the markets seem to be telling a consistent story. After a big shock, lots of money was loosed on the economy; that is already leading to a cyclical recovery; and we can expect it in due course to lead to inflation, and to lower earnings multiples on stocks. There is much more complexity to global markets than that, but we shouldn't lose sight of that message. Survival TipsIt was 40 years ago today. John Lennon was murdered on Dec. 8, 1980, on the steps of the Dakota Building on Central Park West. I used to live within walking distance of the Dakota, and the Strawberry Fields peace garden in his memory that was established in the park facing the building. It was fun to drop in on the anniversary of his birth or death. The garden, centered on a mosaic with the word "Imagine," would be full of people, many with guitars. Festooned with candles, flowers, and letters for the deceased man, the place would host a 24-hour vigil of improvised Beatles songs. Such gatherings aren't allowed at present. So let me suggest some tunes to keep body and soul together. Possibly my favorite post-Beatles Lennon song is Jealous Guy, which my generation of British teenagers discovered through this beautiful cover version by Roxy Music; it went to number one in the U.K. a few weeks after Lennon's death. The song that speaks most directly to our current predicament is Nobody Told Me (the chorus is "nobody told me there'd be days like these"; too right). Dear Prudence, his song to Mia Farrow's sister, which appears on the White Album, gave us a terrifying Gothic cover version by Siouxsie and the Banshees, also a part of my teenage soundtrack, and later a version from Alanis Morrisette that was even more ghostly than the original. For my money Lennon's two greatest songs, which really changed people's perceptions of what music could be, were Tomorrow Never Knows and A Day in the Life, the final tracks of Revolver (1966 — less than three years on from She Loves You) and Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967). Both were written by Lennon and owe much of their finished brilliance to Paul McCartney and George Martin. Both sound radical now; it's hard to imagine how they would have sounded to people hearing them for the first time in the mid-1960s. Both are more or less impossible to improve upon, but digging around I have found a few people who tried to cover them. This is Neil Young performing A Day in the Life, while I was amazed to discover that Phil Collins had done a cover of Tomorrow Never Knows. It was recorded in the weeks after Lennon's murder, and I'm even more amazed to discover that it's actually quite good. Finally, let me offer this live version by the 1990s English indie band Ride, recorded on someone's iPhone at a New York concert in 2015. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment