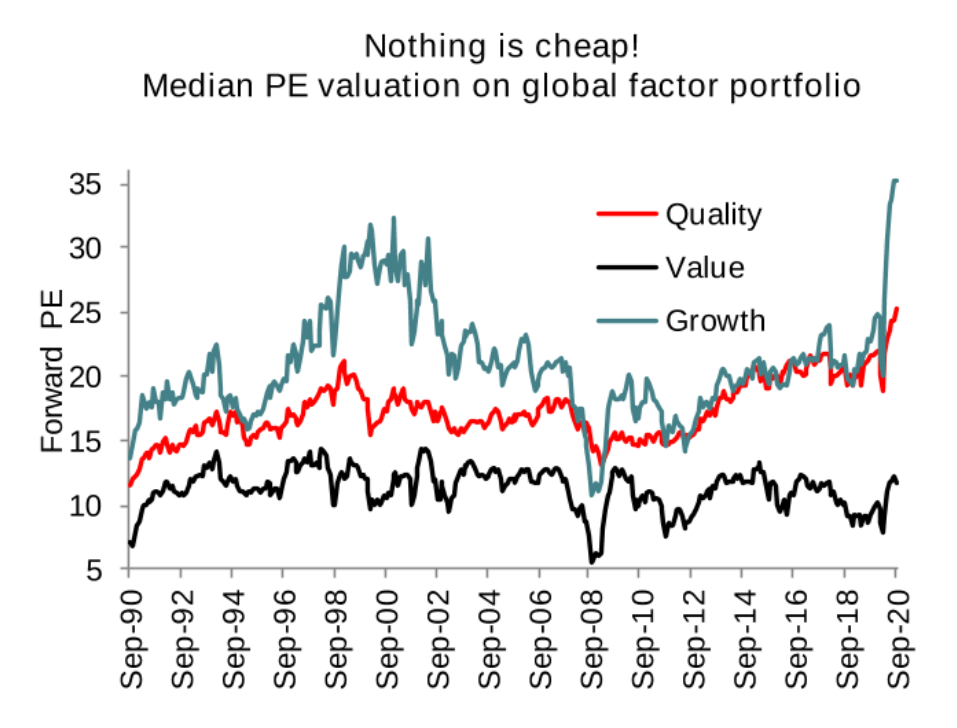

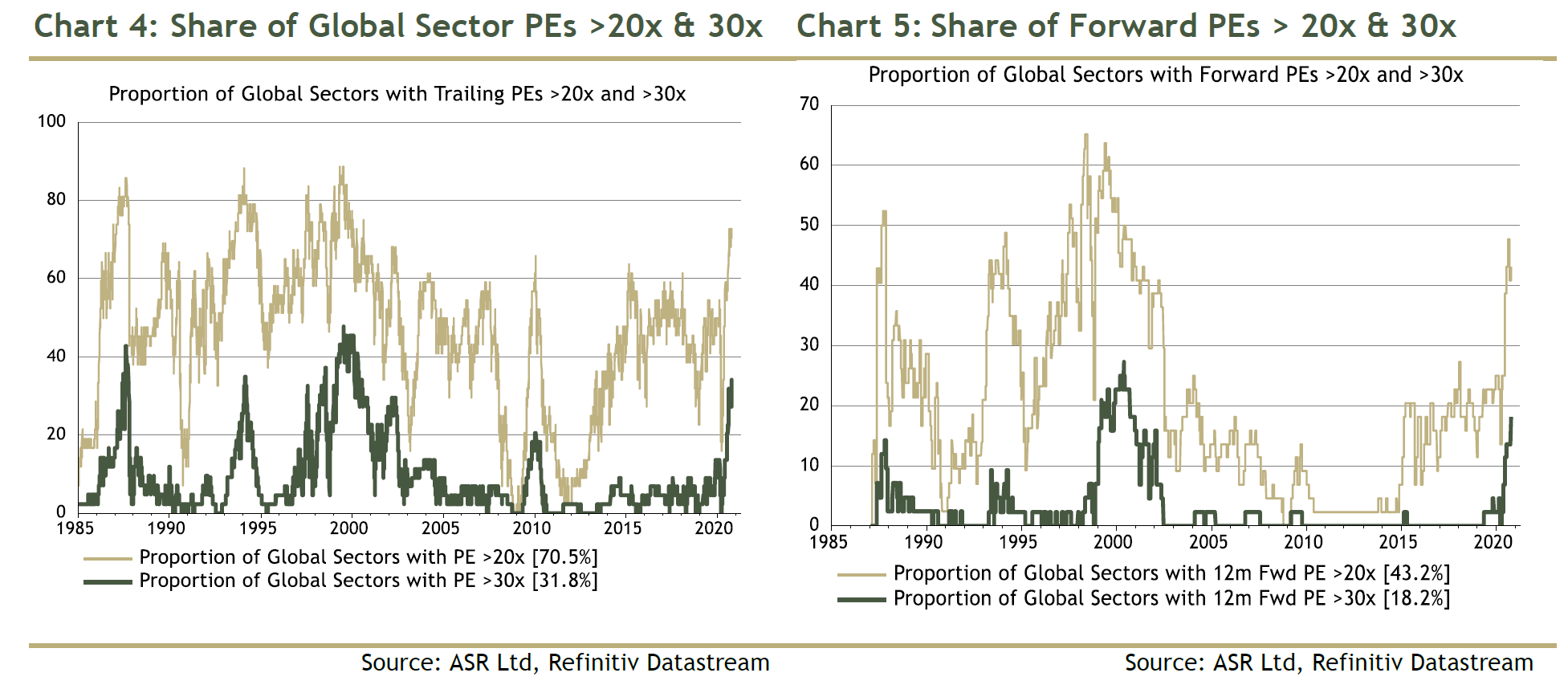

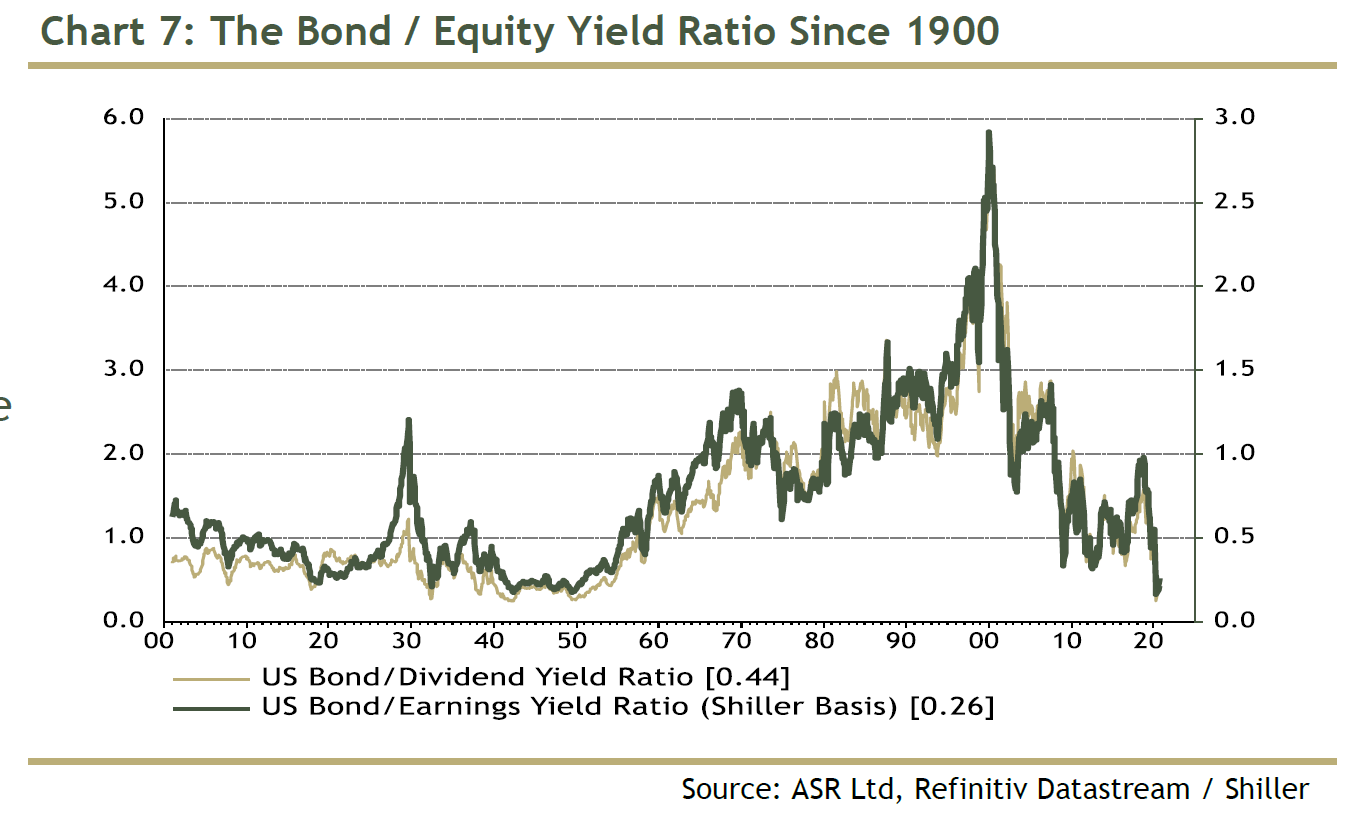

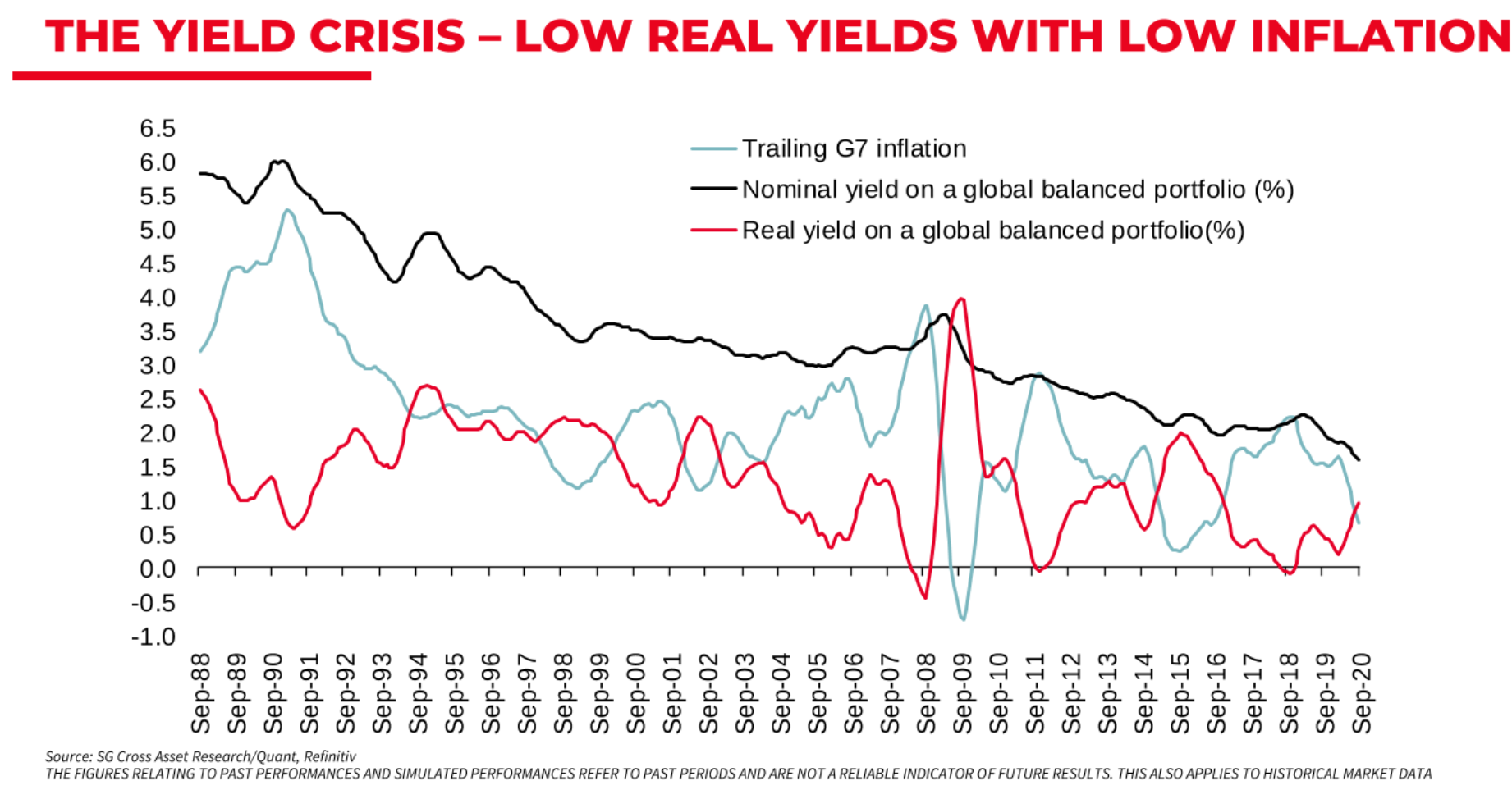

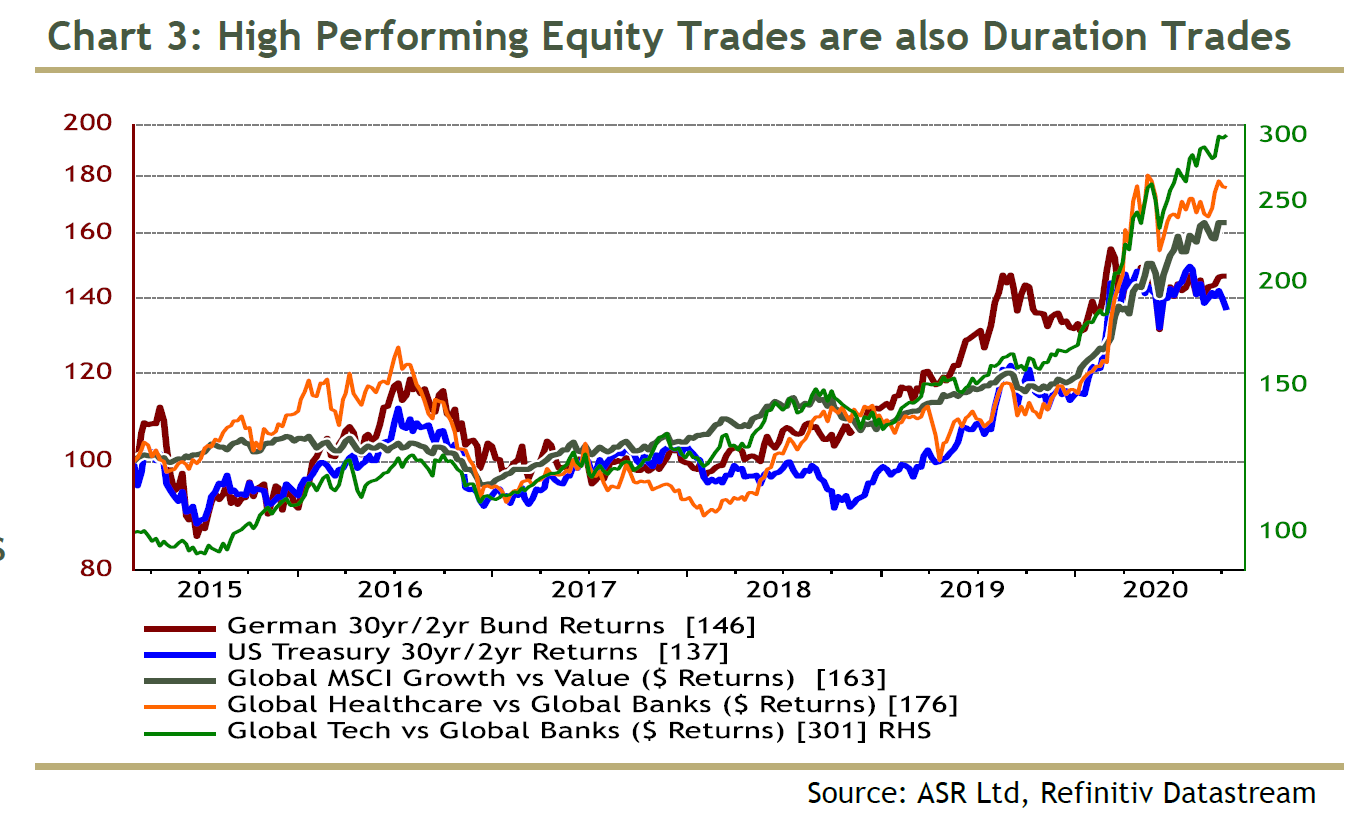

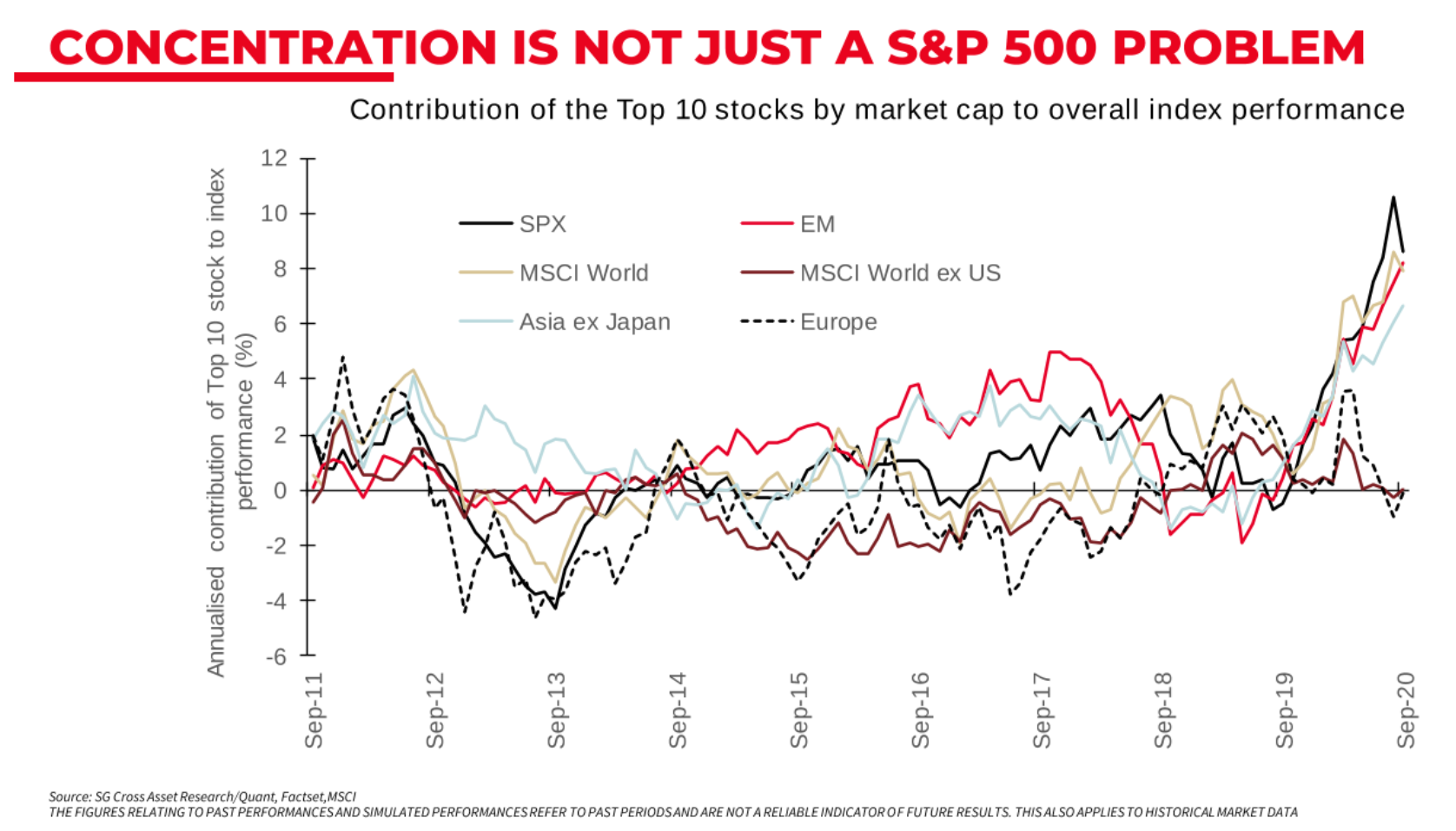

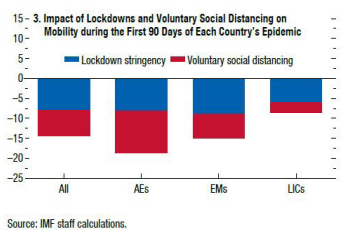

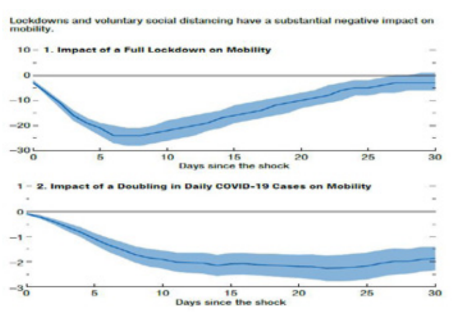

There's Nothing to Buy Investors face two serious and linked problems: Nothing is cheap, and government bonds no longer work as a diversifier. Two separate presentations I received this week show just how intractable this challenge is. To the argument that the issue of expensive stocks is solely about over-hyped and dominant tech stocks, there are a number of easy ripostes. Andrew Lapthorne, head of quantitative research for Societe Generale SA, points out that both quality and growth factors (stocks with strong balance sheets and reliable profitability, and those that are growing steadily) are more expensive on a global basis than they have been in decades. Even much-maligned value stocks aren't cheap by their own standards:  To illustrate that in terms of industries, Ian Harnett and David Bowers of Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. in London show that whether we are using forward or trailing price-earnings multiples, the number of sectors at nosebleed levels of 30, and expensive multiples of 20, is as high as at any time since the internet bubble:  The standard riposte to this is that stocks look cheap relative to bonds. And they certainly do. This chart from Absolute Strategy shows U.S. stocks are as cheap relative to 10-year Treasury yields, on the basis of either earnings yields or dividend yields, as they have ever been. Valuations couldn't be more different from 2000, when stocks were at their most expensive relative to bonds:  But the fact that stocks look so cheap relative to bonds creates a problem for many investors — particularly "risk parity" traders who try to ensure that the risk contributions of each asset class they hold should be equal. Lapthorne suggests this is an outgrowth of his colleague Albert Edwards' infamous "Ice Age" thesis — that yields are steadily declining as world economies lapse into deflation. "In a world of low nominal interest rates, people become very risk averse," he says. "If you have an opportunity of earning 5% in the bank, then you can take some risk — you can afford to lose 10%, because you have the option to go back into bonds or cash. Without a risk-free rate, it reduces your capacity to make more losses." With rates so low, there is a further problem: It is hard to generate any kind of income in excess of inflation, even when price changes are so muted. Stocks are expensive, meaning that their yields are also low, and so the yields on global balanced portfolios are also depressed— and very vulnerable to a return to inflation:  In such an environment, markets become hypersensitive to risk, and polarized. As Absolute Strategy shows in the following chart, more or less any equity trade that has worked in the last few years mimics a bond market bet on duration. In other words, it delivers similar returns to long German or U.S. bonds, relative to shorter-term debt. Big bets on growth against value, and on healthcare or technology against banks, have all ultimately been duration trades — which in turn means that anyone who's made serious money in recent years is vulnerable to a reversal of that trade:  Lapthorne also provides an "Ice Age" explanation for the horrible performance of value. Value stocks aren't performing that badly in economic terms, and they aren't all that cheap; but with yields so low, nobody wants to take a risk. That means piling into those few stocks perceived to be very low risk, such as the FANGs. As Absolute Strategy puts it: "What is there not to like about quasi-monopolies earning super-normal non-cyclical earnings against a backdrop of ever lower discount rates?" It isn't just about the phenomenal success of the FANGs, now coming under serious threat with the antitrust action against Alphabet Inc. There is a similar polarization toward stocks perceived as least risky everywhere except Europe, leading to dramatic concentration of stock markets:  What happens next? If fiscal policy really does continue to grow more expansive — and current events in Washington suggest that that will require a Democratic "blue wave" of the Senate and presidency, which is very far from a given — then that implies higher inflation and yields in due course. Responding will involve either courage (betting on the big trades of the last few years to reverse, and doing difficult things like buying banks and value stocks and wagering against tech), or a leap into complexity. With stocks and bonds both expensive, making money might involve the esoterica of paired trades, betting on one asset to outperform, or diving into private markets. Other than that, there's nothing to buy. From Hope, Fear and Covid Set Free It's not the despair, it's the hope. Variant Perception has produced much interesting research over the last few months suggesting that panic over the coronavirus has been exaggerated. The research group's latest bulletin argues that the greatest reason for fear is fear itself. Research from the International Monetary Fund shows that during the first 90 days of the pandemic, "voluntary social distancing" had a greater impact on mobility than formal government lockdowns:  This suggests that the focus on mandatory lockdowns per se is overdone. There are exceptions, but as a rule people aren't stupid. If there is a risk of catching a potentially deadly virus, they will modify their behavior. Further IMF charts show that a lockdown had far less effect on mobility than a doubling in coronavirus cases:  Not only that, but lifting a lockdown generally had a far more limited impact than imposing one. For all the passionate opposition they have sparked across the world, ending lockdowns hasn't tended to have much effect on how people behave. This suggests that the virus itself, or at least the fear of it, is more impactful on the economy. That in turn leads Variant Perception to say that the prevailing negative coverage of Covid needs to be lightened: As long as policymakers and the media present a more alarmist view of the virus's impact than can be justified by a dispassionate analysis of the data, recoveries will continue to stutter. On the other hand, an easing of the fear portrayed would likely allow recoveries to accelerate at a much faster rate. While this is true, the debate in the last few weeks has grown to include far more voices suggesting that we should move more freely, just as infections have risen again. Journalists need to be confident that it is responsible to tell people it's safe to go back in the water. Otherwise the consequences become hard to contemplate. Besides crowd psychology and fear, the basic logic of collective action has something to do with this. If other people are already active, there is more reason to go and join them. If everyone else is still sheltering indoors, why be the first to break cover? This is a problem I encounter in the office. Bloomberg's head office in New York has been open for a while. The company puts no pressure on us to go in, though does provide a subsidy for those who want to avoid public transport. It's a big open-plan place that provides a very pleasant working environment. But I'm still only going in about once a week. Every time, the place remains nearly deserted. In normal times, going to the office means the camaraderie of being with colleagues, and mixing with guests. By staying at home you feel you miss out. None of that is now true. Indeed the office, which is usually designed to maximize the amount of mingling that employees do, has been redesigned to try to minimize it. This is sensible, and I have no complaints. I'm also happy that it's quite easy to work from home. While few others are going in, the case for spending time on the commute grows much weaker. And so we have a collective action problem. Further, if more people did start going to the office, the problem would switch; I'd be worried about the risks of infection. I gather, thanks to some well-informed Twitterati, that in the advanced game theory literature this is know as the El Farol Bar problem. It goes as follows: - If less than 60% of the population go to the bar, they'll all have more fun than if they stayed home.

- If more than 60% of the population go to the bar, they'll all have less fun than if they stayed home.

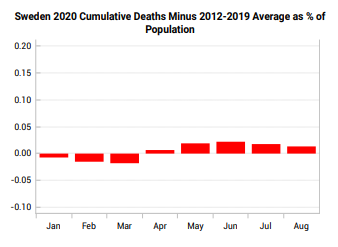

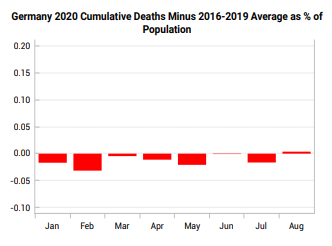

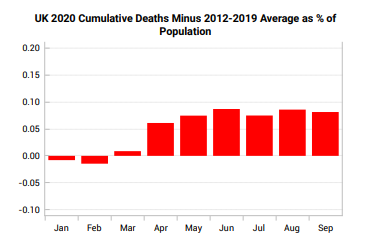

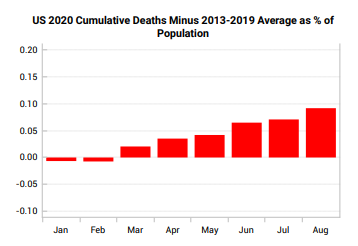

So if everyone assumes that more than 60% will be there, they will stay home, and have less fun. If everyone assumes that less than 60% will be there, they will all go to the bar, and have less fun. At present, people are worried that a lot of other people will also go back to work, and that that will be no fun. So they are staying at home. Dealing with the virus is a problem. Conquering our fear is harder. Dealing with the paradoxes of collective action is the hardest of all. The Corona League Table Variant Perception also introduces one of the fairest ways I have yet seen to compare the impact of Covid-19 on different countries, using excess death measures. Taking the average for the years 2012 to 2019, it compares 2020 deaths as a percentage of the population. This still leaves open the possibilities that unduly harsh lockdowns will lead to more excess deaths in the long run, or that deaths will be below average for a few years in future. But it allows direct comparisons on the one measure that we can all agree matters most. This is the country with the world's most discussed Covid-19 strategy, Sweden:  Whatever the impact on Sweden's economy, Covid-19 has led to more Swedish deaths than usual this year, although far fewer than in many other countries, as we will see. Meanwhile, if there is any major country that seems really worth emulating, it is Germany:  Germany's success has hinged on a brief and well-enforced lockdown followed by successful measures to "test and trace" thereafter. It has been consistent and disciplined. It there's a leading economy not to emulate, it is the U.K.:  Britain has of course been a model of indiscipline; too lenient at first, and then applying a tough lockdown longer than anyone else in Europe, and then making a botched attempt to reopen schools and colleges. Its contrast with Germany is alarming. The U.S., however, is beginning to look almost as bad:  To put these figures in further perspective, the Centers for Disease Control has announced that the number of excess deaths in the U.S. for the year is now nearly 300,000. The secret of minimizing the damage and suffering seems to lie in the boring virtues of discipline and consistency, rather than the big and impassioned debates over liberty that are currently dividing countries with the more serious problems. Survival Tips As we are on the subject of hope and fear, I'd like to recommend a poem by Emily Dickinson, which the revered David Kotok of Cumberland Advisors Inc. published in his regular weekend bulletin on Sunday. It's sweet, effective, and very beautiful: "'Hope' is the thing with feathers," by Emily Dickinson

"Hope" is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all -

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -

And sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

I've heard it in the chillest land -

And on the strangest Sea -

Yet - never - in Extremity,

It asked a crumb - of me.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

|

Post a Comment