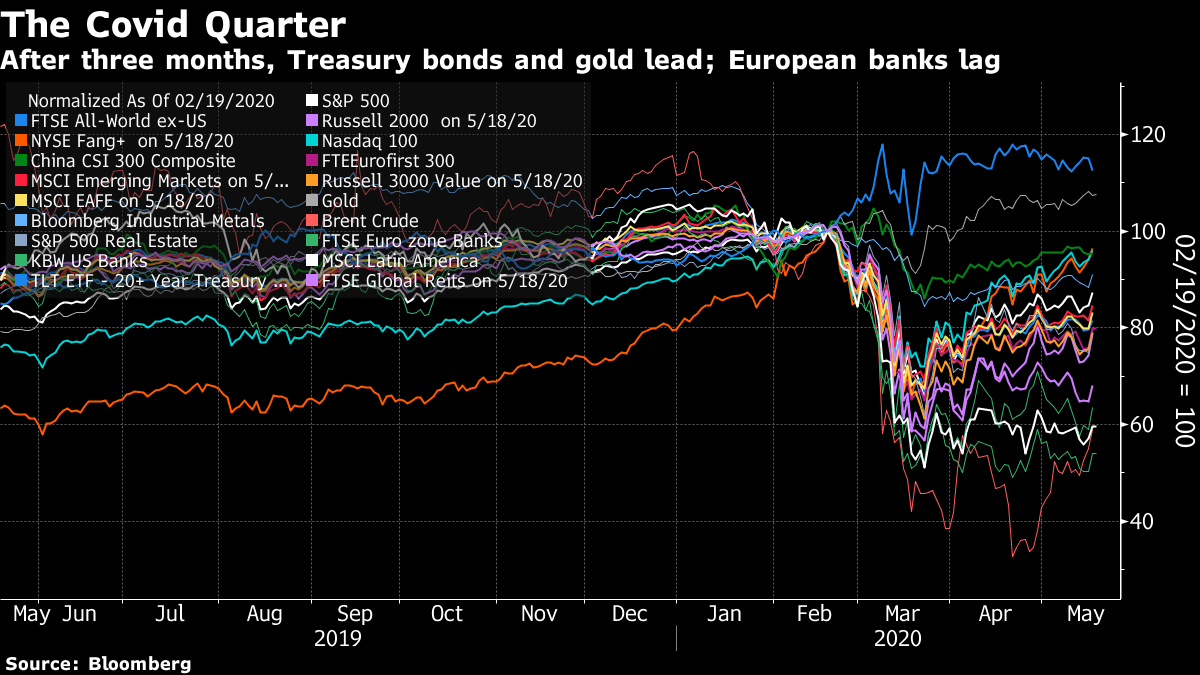

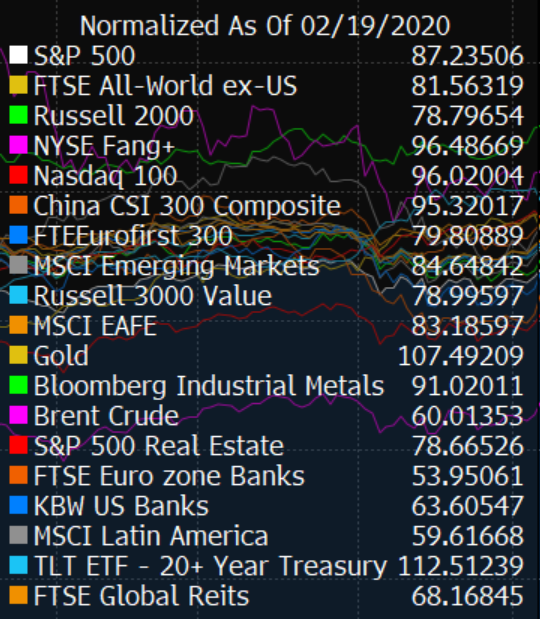

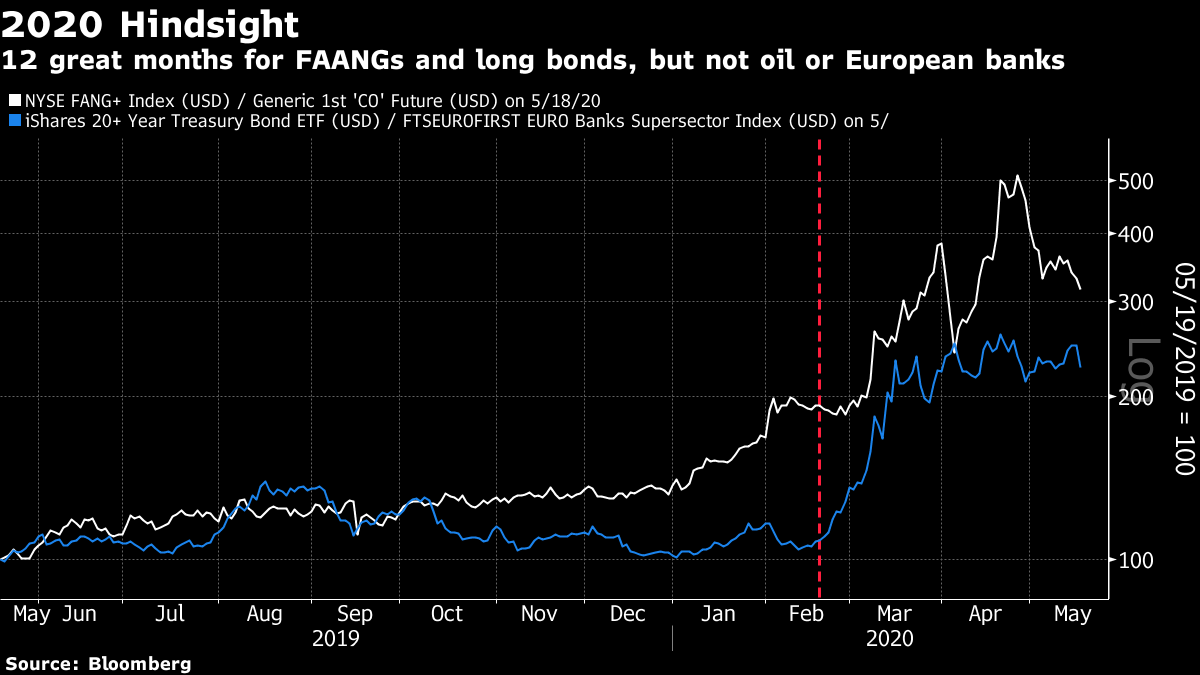

Let's Call It a Quarter Congratulations. As of Tuesday it has been three months — a full quarter since Feb. 19, when stock markets peaked and began their dramatic slide in the face of evidence that the coronavirus had spread beyond China. It feels much longer than that, and not just because February had an extra day this year. It does, however, give us a good opportunity to see how far we've come. On any sensible reading, these have been three of the most extraordinary months in financial history. This is a chart of the last year, showing how a range of different asset classes have performed over the last 12 months. It is normalized so that all of them were at 100 on Feb. 19. The range is staggering:  As this might be difficult to read, here is a screenshot of how each index was performing as of close of trade on May 18:  It might have been guessable three months ago that long bonds and gold would be the best places to shelter, and even make money. Anybody who foresaw that the equity sectors closest to breaking even would be the FAANGs, tech stocks in general, and Chinese A shares, however, deserves a medal. None of them are down even as much as 5%. China has been rewarded for what appears to be a strong rebound from the lockdown in force three months ago, while the FAANGs are perceived as active beneficiaries of virus restrictions. They had a poor day Monday as everyone grew excited about the possibility that a vaccine would cut the lockdowns short and avert a second wave. Some things about financial crises seem permanently true. Whatever the cause, Latin America always gets it in the neck. And nobody has confidence in banks. The appalling performance of banks on both sides of the Atlantic came despite all-out desperation tactics from central banks that surely stoked moral hazard — and so suggests that what the central banks did probably was an unpleasant necessity. But when the motors of finance are perceived to be so weak, it also grows harder to justify any serious expectation of good times ahead on the market. Among the more surprising findings: Real estate has had a terrible time. Real assets are supposed to prosper when times are hard, and the dividends that real estate investment trusts pay should become far more attractive when 10-year Treasury yields have taken root below 1%. But whatever support central bankers are offering to small businesses, it is obvious that investors don't believe they can continue to offer those yields. Buying real estate at this point is seen as a big bet on tenants' continued ability to pay their rent, and investors don't want to make that bet. For years there was an iron inverse relationship between Treasury yields and REITs' performance compared to the main market — lower yields meant stronger share prices. The coronavirus killed that relationship:  Now, for an early installment of my annual year-end exercise, where I ask an imaginary hedge fund called Hindsight Capital LLC to tell me its best trades of the previous 12 months. Armed with the knowledge that the world would fall victim to a global pandemic at the end of February 2020, what trade would Hindsight Capital have made 12 months ago? Or three months ago at the top of the market? Assuming it is restricted to broad asset classes (and the FAANG stocks are so huge these days that I think they count as an asset class), then here are the best long-short trades of the last 12 and three months:  Shorting crude and putting the proceeds into the FAANGs would at one point have produced a profit of more than 400%. It is still showing a gain of more than 200%. And if you had shorted euro-zone banks on Feb. 19 and bought Treasury bonds you would have made 108%. We should note that these profits come from a trade which, on the face of it, suggests we are still on a disaster footing. It's not healthy. Marks My Word "No amount of sophistication is going to allay the fact that all of your knowledge is about the past and all your decisions are about the future." That deathless quote comes from my interview with Oaktree Capital Group's Howard Marks at the CFA Institute's annual conference, which you can find here. (You need to register first, but it takes less than a minute.) For yet more interrogation of Marks, you can find his interview with Eric Schatzker for Bloomberg Front Row here. I think it is worth summoning Marks's invocation to intellectual humility on the day when markets went ballistic over news of a promising early stage test result for a coronavirus vaccine. (There were also encouraging reports from Europe, and worrying signs on the U.S.-China relationship, but it was plainly the vaccine that excited Wall Street.) That news is unquestionably positive. If there is really a safe and effective vaccine ready for all of us before fall, then the immediate future of the world looks much better. But I lack the scientific or public health knowledge to say exactly how strong the chance of that is, on the basis of this news, or how much that chance has risen. We can, however, fall back on Marks's use of cyclical methodology. The Covid crash is emphatically not part of the normal cyclical progress of the economy. It is more what he would call a "sunspot." But the basics of cyclical and contrarian investing remain intact. The more expensive an investment, the harder it is to make money, and the more important it is that you are right about any given view of the future. How important is it to be right about a positive future at present? Here is the prospective price-earnings multiple of the S&P 500 over the last 25 years, using Bloomberg's measure of consensus expected earnings for the next 12 months:  Monday's vaccine rally has brought us to a prospective P/E not seen since December 2000, when a historically inflated market was in the process of returning to reality. This time, the valuation extreme has been reached at a point when the economic future looks far darker and more uncertain. How can this possibly make sense? There are two broad justifications. One is that we should all learn from the last decade not to fight the Fed. If it is going to keep yields so historically low, then a higher earnings multiple (and hence a lower earnings yield) on stocks could make sense. But Marks argues that we shouldn't necessarily expect the Fed to remain limitlessly strong forever. If you look at the fate of REITs, and of banks in the euro zone, it's evident there are deep fears that the second-order financial effects of the crash will lead to a solvency crisis, as tenants and debtors cannot pay their bills. The other justification for a high multiple is great confidence within the market that prospective earnings are too low. In this case, we need to expand that a little. The current prospective earnings refer to 2020, which will obviously be a bad year, even if there are arguments about how bad — a swift bounce back in 2021 might conceivably justify a multiple at this level. And without regurgitating a lot of the painful arguments we have all been reading for the last three months about second waves, lockdowns, and the risk that a return to "normal" will only be at 90% of capacity, that strikes me as about the best any of us can hope for. Could it happen? Yes, and the chances that this comes to pass may have risen a little bit with the latest news on the hunt for a vaccine. Does it really make sense to have bid stocks up to this level already? No. To paraphrase Marks once more, we should know what we don't know, and not position ourselves for the best of all possible worlds. Survival Tips Books truly came to my rescue while I spent a week in bed. Reading is immersive in a way that consuming no other medium can be, and it broadens the mind. Or at least, in the case of some of the fiction I read last week, it can be very entertaining. I found myself challenged on Twitter to provide a photo of the six books on my nightstand. There are rather more than that, but here are the six closest, all of which I have started, and all of which I intend to finish — but none of which I have finished yet:  I got through the first eight weeks of the lockdown without reading any book from cover to cover. Somehow or other it's difficult in these conditions to switch off and read. I resolve to change for the next few weeks. It's good for spiritual and mental health to read a book. So there is a survival hint. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment