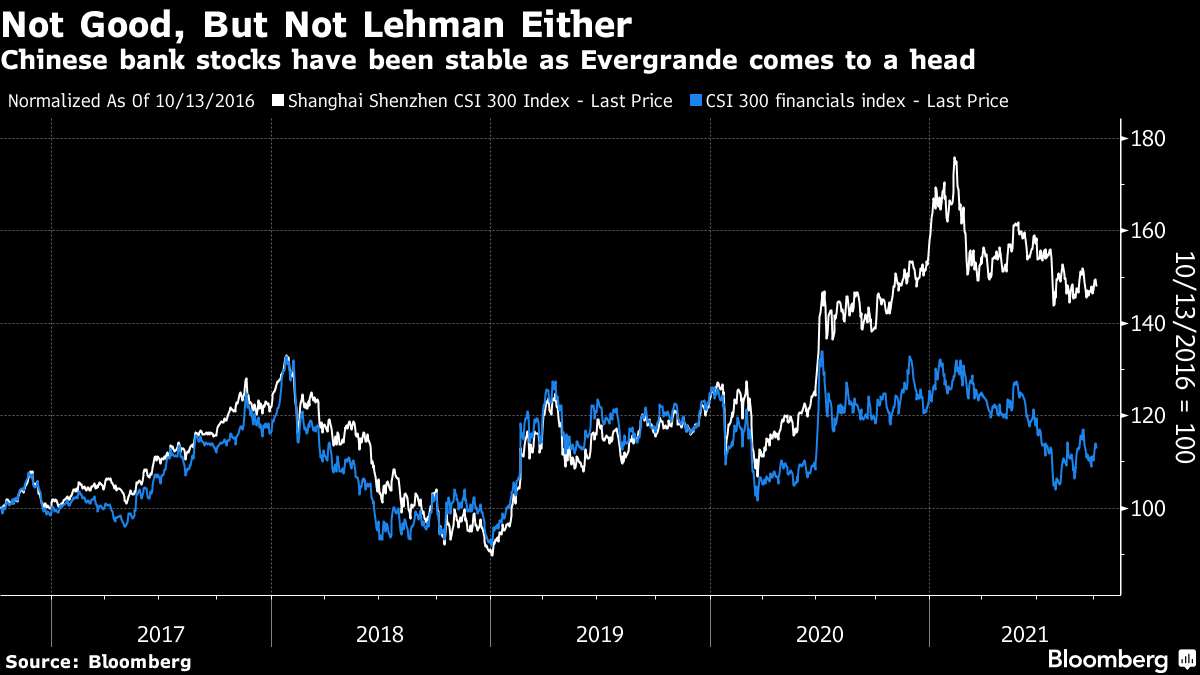

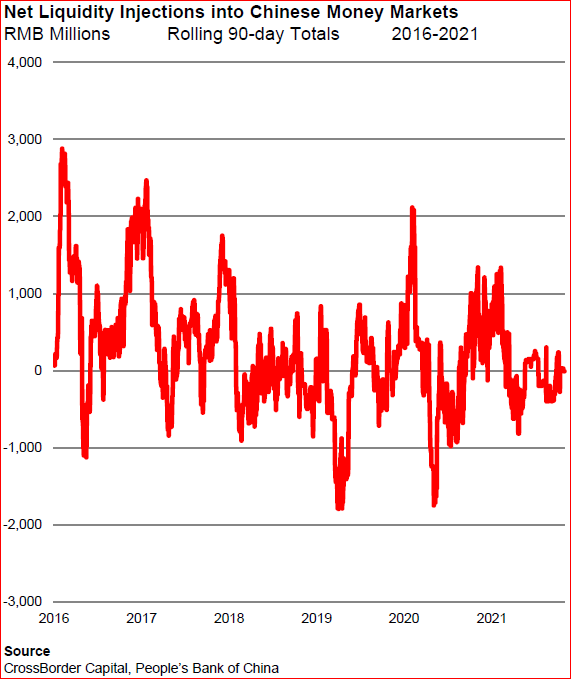

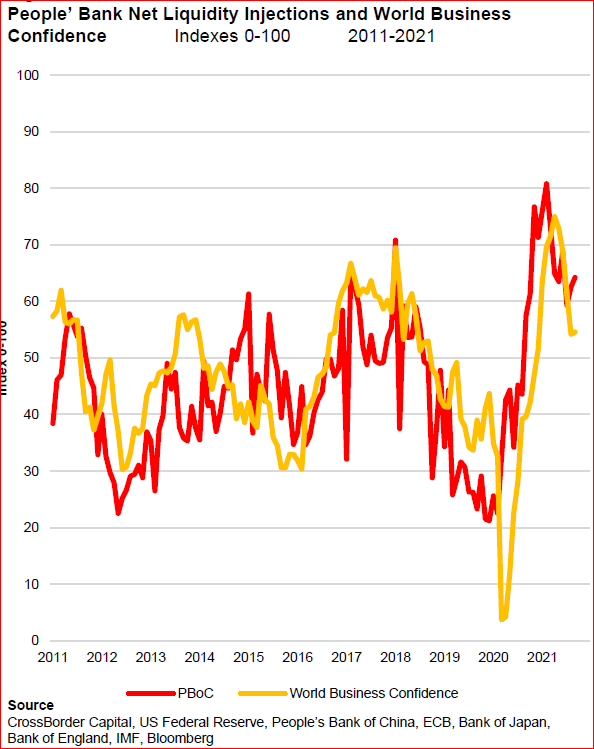

| Three weeks after property developer China Evergrande Group began failing to make scheduled payments on its debt, prompting a one-off shock to U.S. equity prices, there is no obvious reason to feel any more relaxed about the situation. The Chinese real estate sector itself is selling off ever more aggressively, and its descent has only accelerated this month. This is how the broad high-yield real estate sector in China has moved over the last six years:  The vital question for many investors has been whether the problems for speculative real estate will cause broader contagion, either through cascading losses in the financial system or through economic weakness. The first continues to look unlikely, while the second — an economic slowdown of which Evergrande is both a cause and a symptom — grows more likely with time. It shouldn't be surprising that China is avoiding an all-out financial crisis: Its leaders have made clear for a while that crisis prevention is a priority. That involves clamping down on leverage and speculation, making for very poor performance by bank stocks, which missed out on the brief melt-up in Shanghai and Shenzhen earlier this year. But it also helps to explain why bank stocks have managed to outperform the market slightly as Evergrande's difficulties have become acute:  The broader issues for the Chinese economy should become clearer with the raft of macroeconomic data due from the government later this week. But if we look at the decisions made by the People's Bank of China and at levels of liquidity in the system, it seems reasonable to prepare for a slower rate of overall growth. As the following chart from London's CrossBorder Capital Ltd. shows, China's central bank is trying to keep injections of liquidity into the system low and consistent. It quite easily might have chosen to flood the system with money to keep the economy moving, as it has done several times in the recent past, but it isn't doing that:  CrossBorder Capital also has a nifty chart to show how net liquidity injections by the People's Bank of China, perceived to be a crucial variable in the country's short-term growth, correlate almost perfectly with global business confidence over time. If the bank is trying to hold the line and engineer a "controlled" credit deflation, that may well be good news for the medium and long term, but it could have a very nasty effect on perceived global growth prospects in the next few years:  Michael Howell of CrossBorder puts the latest moves into a global context. Remember that Evergrande first ran into trouble because regulators tried to rein in property speculation: [T]ighter Chinese liquidity may well explain the intensity of the latest economic slowdown. This Chinese policy change represents a significant switch away from 'growth at all costs' to 'stability' and it embraces the CCP's latest political slogans, namely 'common prosperity'. This 'new' policy arguably started in early 2016, following the G20's Shanghai Accord, as a plan to stabilise the then surging US dollar, and it then moved to explicitly curtail excess shadow banking lending and real estate speculation some two years ago. Evergrande is an unambiguous casualty of this policy. There will be others, but, unlike the 2008 Lehman Crisis, this is a 'controlled' credit deflation and… the PBoC is not yet showing signs of reversing its stance. The chart shows a rolling 90-day total of PBoC liquidity injections into money markets. RMB 640 billion of cash was injected ahead of the Golden Week holiday in early October 2021, but RMB 510 billion (i.e. 80%) of this has since been removed again to re-establish the status quo. Despite the fragile domestic economy and Evergrande fall-out, Chinese policy-makers are focused on their 'stability' remit.

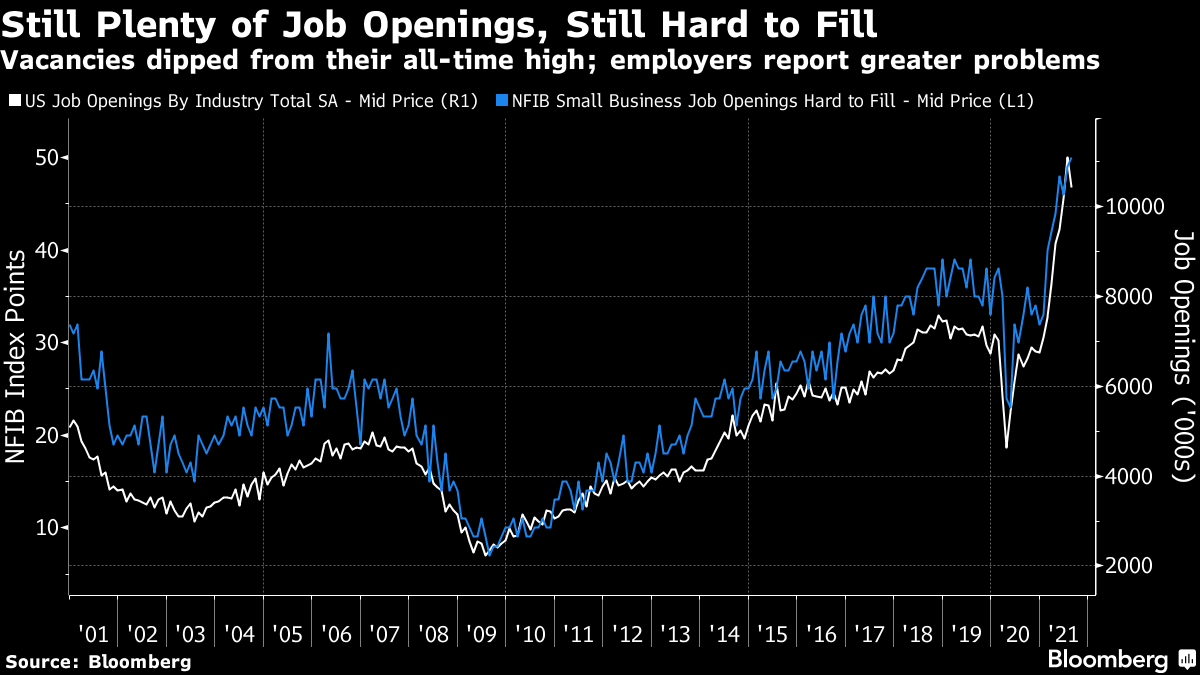

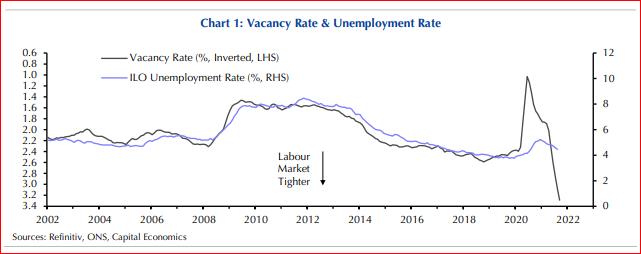

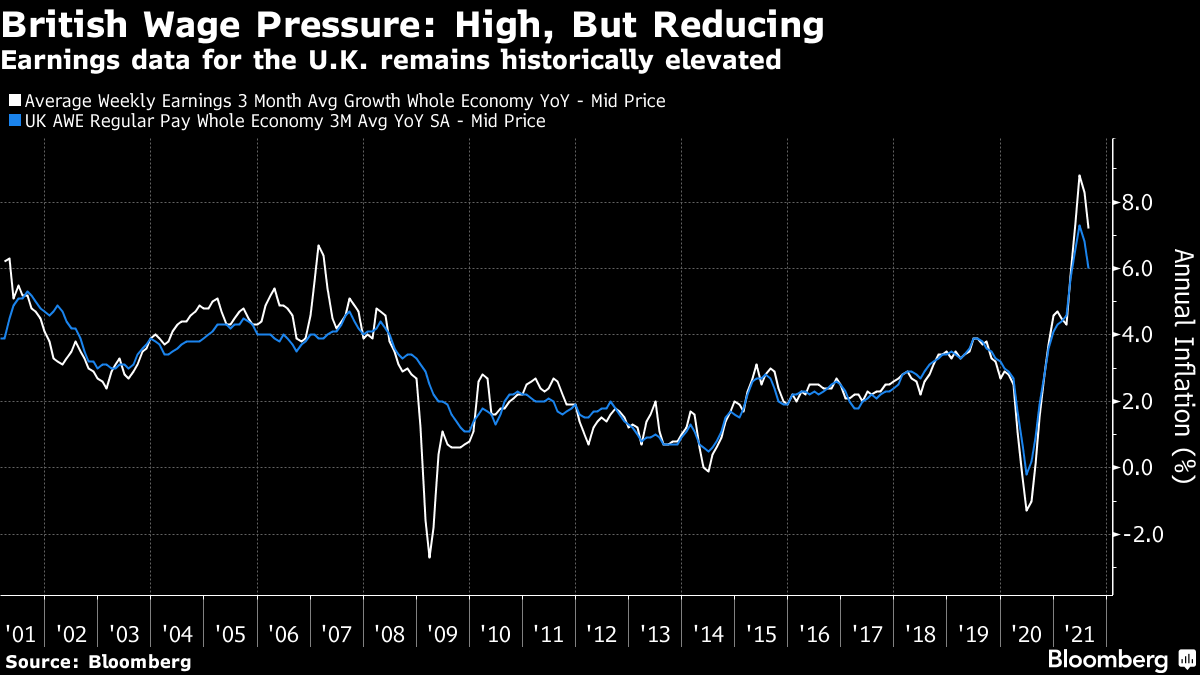

It would be wise to keep an eye on the Evergrande situation. There have been plenty of justified criticisms over the last two decades of China's growth policies, which have exported deflation and unemployment to the rest of the world. We might now be about to find out the alternative. While the possibilities of a Lehman-style disaster now seem much lower, Evergrande could give the entire world its first test case of what happens when China prioritizes stability over "growth at all costs." As we all now know, something odd is going on in Western labor markets. Whether this is because of a "Great Resignation" or "Great Retirement," as people are inspired by their pandemic experience to seek better work or to retire, or whether it's because school closures make it hard to deal with childcare issues, record numbers of jobs remain unfilled. That in turn implies inflationary pressure ahead, as employers feel that they have no choice but to raise pay if they want to attract new workers. Tuesday brought two surveys in the U.S. to confirm this intuition. The National Federation of Independent Business's monthly survey of small business managers found that the number finding jobs hard to fill had increased further to a new record. Meanwhile, the official Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey numbers showed a slight reduction in vacancies. But they remain above 10 million, at a level never seen before August. The two surveys confirm each other more or less perfectly over time:  What is going on? It's important to note that this isn't a purely American phenomenon. The U.K. also published new labor data Tuesday, in an atmosphere where many are braced for higher rates from the Bank of England. They showed a huge increase in the number of vacancies, out of all proportion to the state of the overall labor market, for which the unemployment rate was lower than it has been for much of the past decade. As in the U.S., jobs are far harder to fill than they would normally be when the economy is this healthy:  In the U.K., as in the U.S., there are already signs of increasing wages. As the British suffer from similar social discontent to that seen across the Atlantic, this is not necessarily bad news. If people are paid more, they tend to be happier, and they also tend to spend more, which will make others happier. The problem is that prices tend to be raised in the process. This is what has happened to British wages over the last 20 years, according to the official government data:  While wage inflation dropped last month in the U.K., this was largely due to technical factors, as the special Covid-related furlough scheme ended Sept. 30, as explained by Paul Dales, chief U.K. economist at Capital Economics: Admittedly, the unwinding of the boosts from the furlough scheme and the change in the composition of employment meant that the 3myy rate of average earnings growth fell from 8.3% in July to 7.2% in August. But the [Office for National Statistics] said that excluding those distortions, underlying earnings growth accelerated from a range of 3.6-5.1% in July to 4.1-5.6% in August.

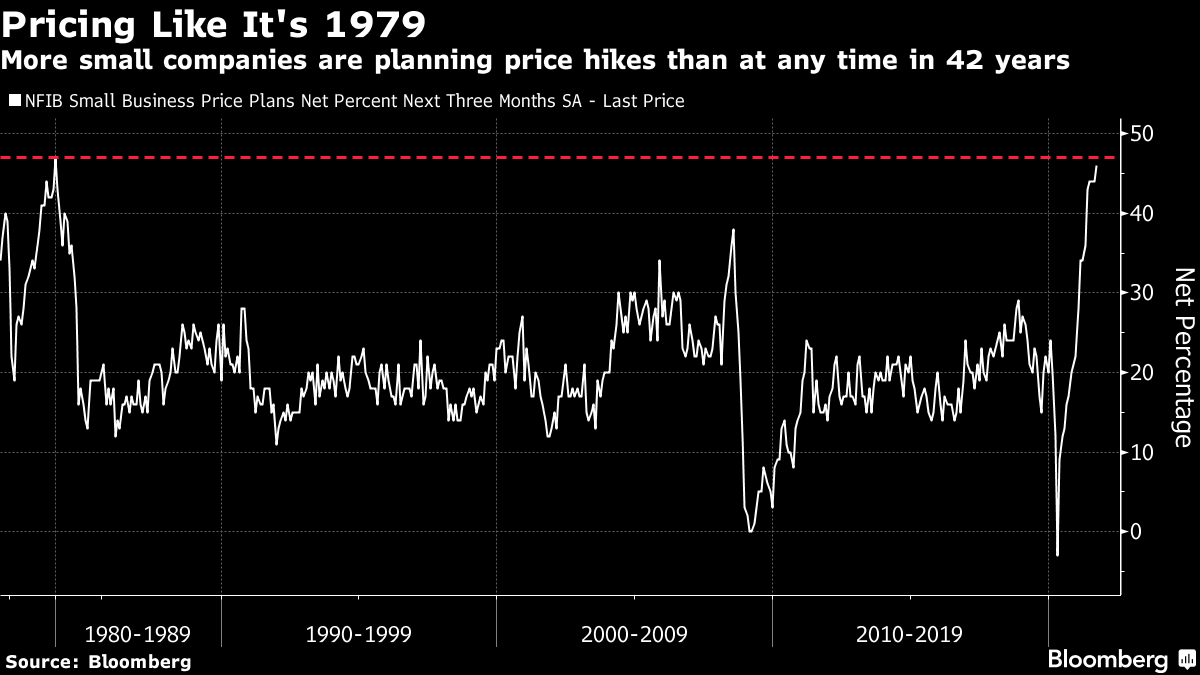

Both countries had specific programs, which are now being relaxed, for tiding people through the Covid shutdown. The U.K. also is dealing with the sharp increase in natural gas prices in recent weeks and the post-Brexit shortage of truckers. Both of these factors will tend to boost inflation, raising the risk that inflation expectations become entrenched. That puts great pressure on the Bank of England to raise rates within the next few months. The ultimate logic of tight labor markets is for companies to raise their prices to the consumer, for two reasons. First, with capacity limited, companies want to raise prices to keep their revenues steady. Second, if they are going to raise wages, it helps to raise revenue. And indeed the NFIB survey shows the proportion of small businesses preparing to raise prices in the next three months at its highest in more than four decades. It has only once been higher, amid the oil crisis of 1979:  And that in turn translates into higher inflation expectations among consumers. Monday saw the publication by the New York Fed of its survey of consumers' expectations. Orthodox theory holds that rising inflation expectations can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, although this has become controversial within the central bank. If raising expectations can indeed become habit-forming, then that is a problem. Expectations for inflation three years hence are now above 4%, and far in excess of any number reported by consumers since the survey started in 2013:  Those numbers help to confirm a shift in sentiment over the last few weeks. Those believing that the current dose of inflation will be transitory are now in a minority. In what could be an important symbolic gesture, Raphael Bostic, president of the Atlanta Fed, said on Tuesday that "transitory" had become a "dirty word," and that he and his employees had to put a dollar in a "swear jar" if they ever used it. In more central bankerly language, he said: It is becoming increasingly clear that the feature of this episode that has animated price pressures — mainly the intense and widespread supply-chain disruptions — will not be brief. By this definition, then, the forces are not transitory.

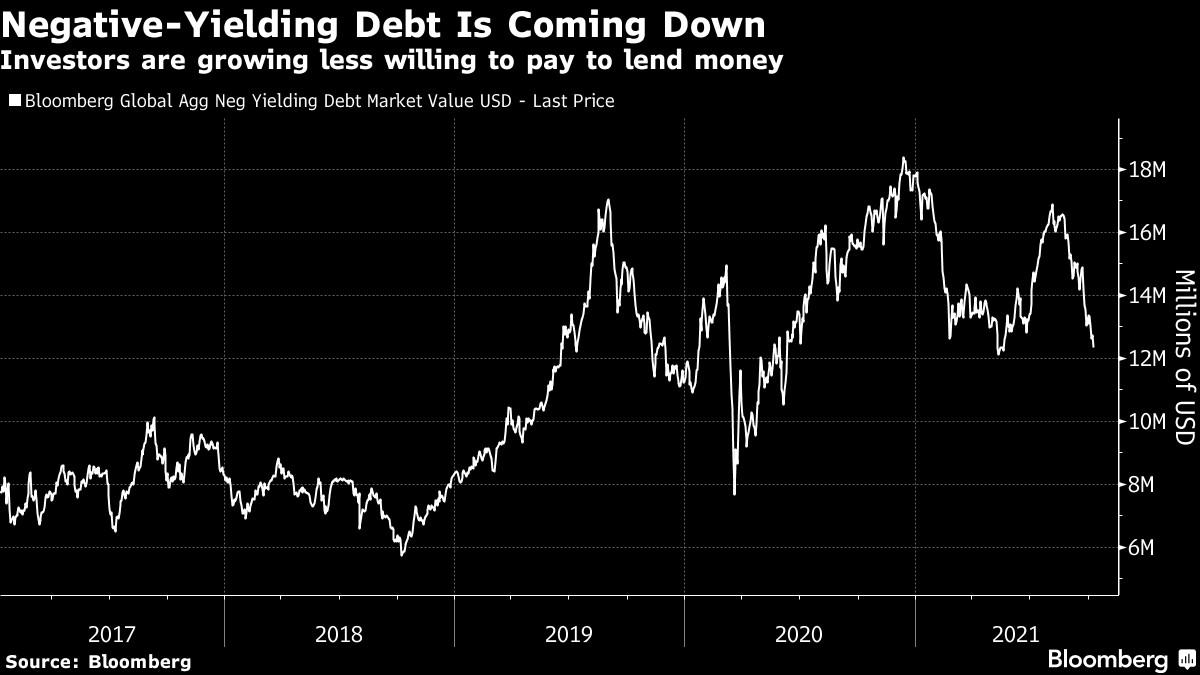

It's always possible that the September CPI data, due within a few hours of this newsletter's publication, will cause a shock, shifting sentiment back. But at present, the notion that this inflation is merely an offshoot of the pandemic and will soon go away has been jettisoned. One consequence is a rise in positivity. Negative yielding debt is not compatible with a belief that inflation is here to stay. The most important manifestation of this positivity is in continental Europe, where many had slipped into the assumption that the region was destined for full-blown Japanification. They are more positive now. For example, French four-year inflation breakevens were negative as recently as last November, suggesting a remarkable malaise. They are now close to 1.5%, and well above their pre-pandemic levels:  Negative yields are not compatible with inflation expectations of this magnitude. The most important development could come in neighboring Germany, where the 10-year bund, one of the world's linchpin financial instruments, has been negative-yielding for more than two years. It is now yielding more than -0.1% for the first time since May 2019. This is still an extraordinarily low rate, but reaching a point where Germany's government actually has to pay people for lending to them again would be a major psychological barrier. Negative bund yields were greeted with disbelief when they arrived, but they now almost seem to be the norm. Changing that would be a big deal:  Meanwhile, the total global stock of negative-yielding debt is beginning to reduce:  To be clear: There is still an obscene amount of negative-yielding debt in the world. And even if German 10-year bund yields rise all the way to +0.01%, they will still be incredibly low. But squint and cross your fingers, and you might just see the deflationary psychology beginning to ebb. If there's one movie I can recommend wholeheartedly to go and watch when you're out of your brain with jet lag, it's "No Time to Die," the latest James Bond epic. I saw it over the weekend, and while it may be escapist nonsense, it's still absolutely brilliant escapist nonsense. There is indeed much less sexism than there used to be; it's at times genuinely funny and at others genuinely moving. And unlike most other Bond films, you could even say that the ending (which I won't spoil) comes as a surprise. I really suggest seeing it on a big screen. As for my favorite Bond songs, which I'm sure you wanted to know, I like "Skyfall" (by Adele), "A View to a Kill" (by Duran Duran, with an all-time-great video) and "The Living Daylights" (by A-ha), in no particular order — plus Shirley Bassey's unbeatable "Goldfinger" and "Diamonds Are Forever." |

Post a Comment