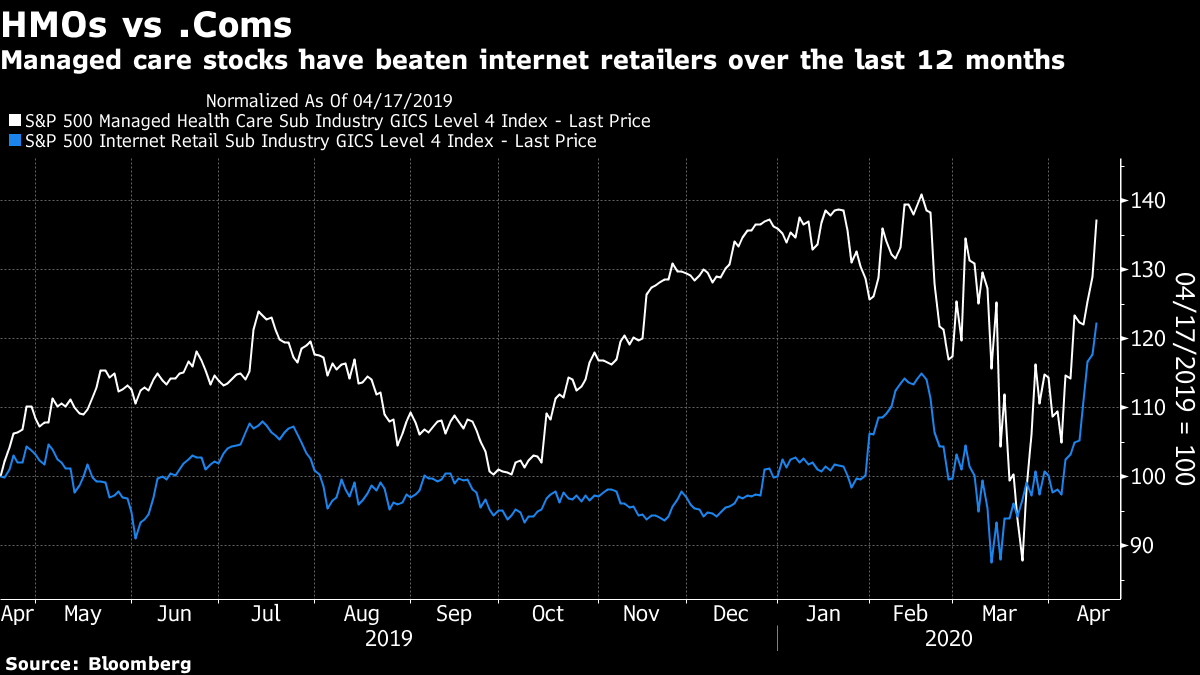

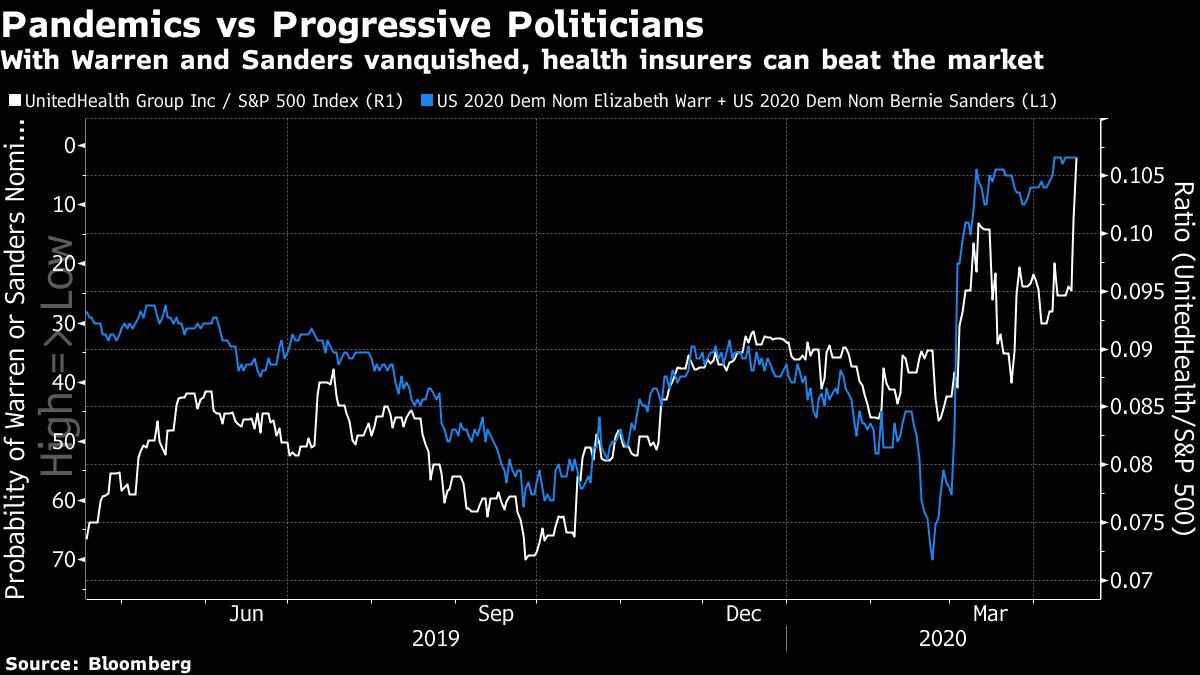

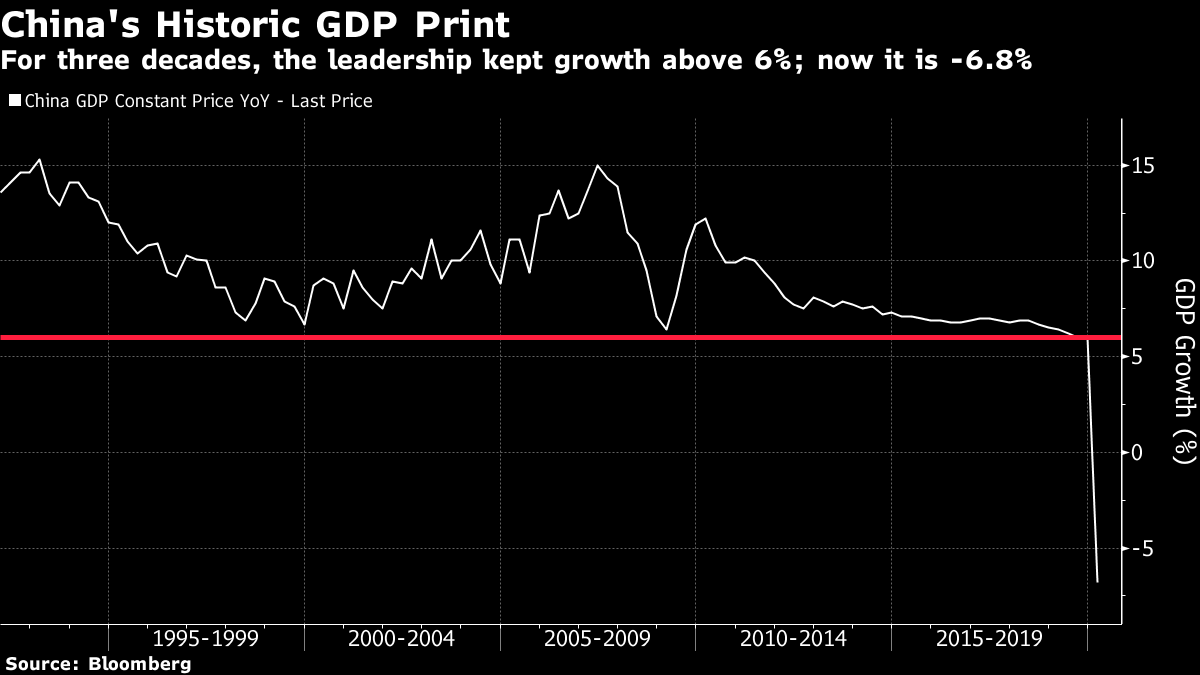

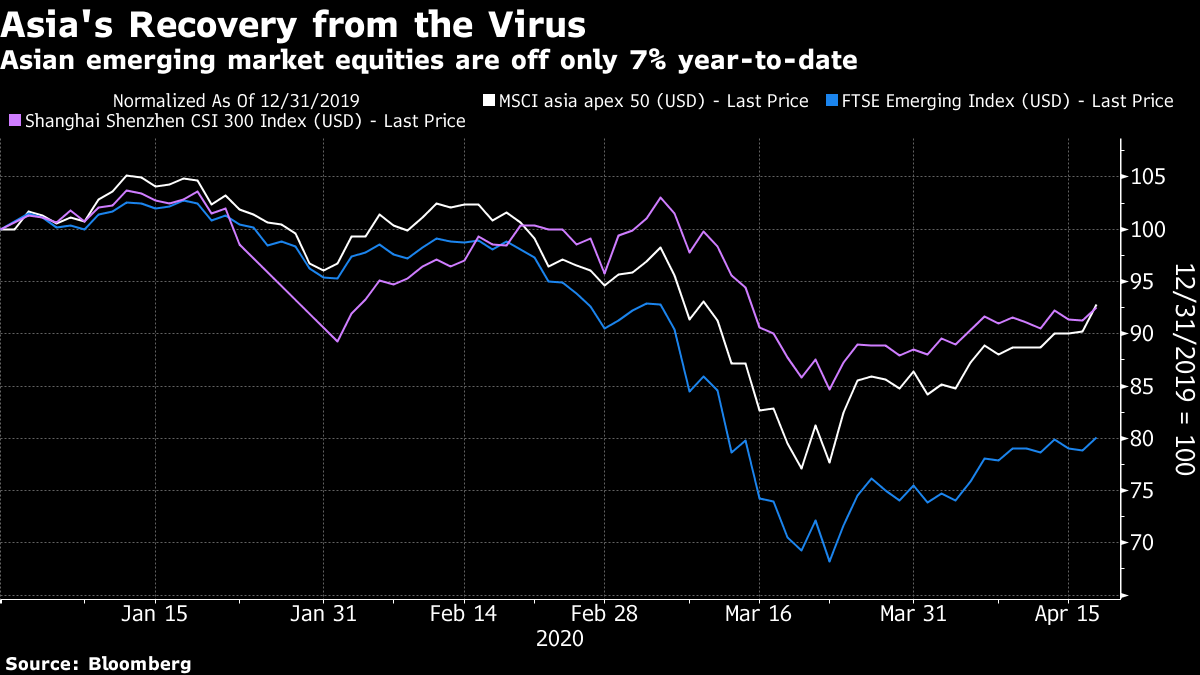

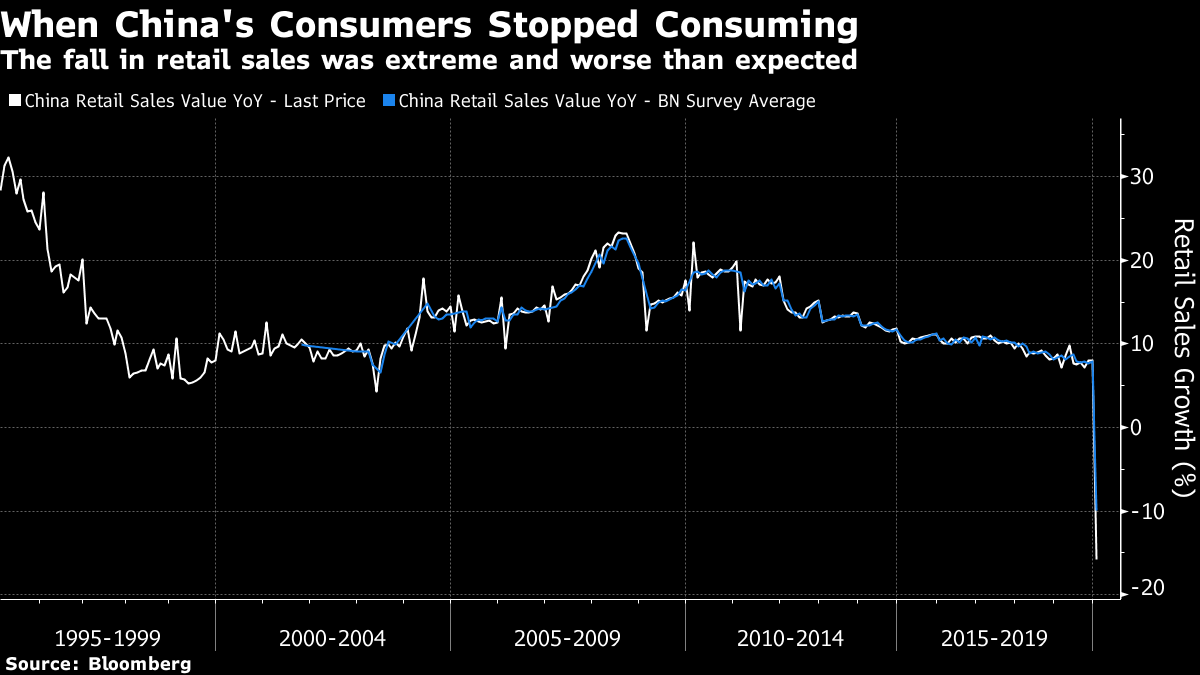

Pandemics Help Health Insurers You learn some interesting things during earnings season. For example, you would think the implications of a pandemic for health insurance companies would be straightforward. After a hurricane, property and casualty insurers have to pay out more in claims and their profits go down. You would expect the same for health insurance companies. You would, however, be wrong. On Wednesday, UnitedHealth Group Inc. was the first of the U.S. health management groups to announce its profits, and they have held up fine. Earnings per share were virtually unchanged from the first quarter of last year, and slightly ahead of expectations. And so the stock market went to town. The S&P 500 managed healthcare sector gained 2.9% on Wednesday and another 6.4% on Thursday. Remarkably, over the last 12 months these companies have not only made money for their shareholders, but more of it than internet retailers:  What is going on here? In part, the health insurers are helped by a perverse substitution effect. A large part of their job is to pay for elective surgeries. By the end of the first quarter, far fewer elective surgeries were being performed, as hospitals readied themselves to fight Covid-19, and so they had less to pay out in claims. People are also going to the doctor less. Critics can harshly point out that health companies shouldn't be doing well out of a pandemic; more realistically, the experience suggests that health insurers in the U.S. aren't about protecting risk, but about providing a means of payment and cost control. These tasks are left to the government in other developed countries, but it seems that there is good money to be made from it in the U.S. Politicians have suggested that this might explain the well-known statistic that the U.S. pays more per head for its healthcare than anyone else, while getting noticeably poorer results than many countries in western Europe. If there is room for a range of for-profit insurers to profit from a role as intermediaries in the healthcare system, it is hardly surprising that this drives overall costs up. And that leads to the other greater reason why the health insurers are doing so well this year. Political risk is perceived to have diminished dramatically. Over the last 12 months, first Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and then Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont seemed likely to clinch the Democrats' nomination for the presidency. As this chart shows, UnitedHealth's performance has been the almost perfect inverse of the perceived chance that one of these two would be nominated. Since the two politicians who were talking about abolishing private insurance have been vanquished, its share price has rallied:  This is one of many intriguing examples where the wisdom of the market conflicts with the received wisdom of society as a whole. The opinion pages are full of predictions that the U.S. will move closer toward nationalized healthcare and a single-payer system as a result of the pandemic. Even figures on the right are talking about extending the social safety net somewhat, to avert the possibility of something more drastic. Joe Biden, who the Democrats now seem almost certain to nominate, is in favor of a "public option," which means a government-run health insurer that would try to force down the premiums for-profit health insurers can offer. And the prediction markets give him a 50-50 shot of winning the presidency. Just as markets seem confident that the current lockdown will be the last, against the conventional wisdom, so also they seem confident that the U.S. model of health insurance can survive both the pandemic and the U.S. political process. It is certainly managing to survive in good shape so far; but the market seems a tad overconfident that it can continue. China's Historic Economic Number China's GDP growth data arrived Friday morning in Asia. After three decades of keeping the Communist leadership's implicit post-Tiananmen promise of maintaining annual growth above 6%, the line has been broken and in spectacular fashion. In the first quarter, Chinese GDP shrank by 6.8% in comparison with the first quarter of last year.  This is a truly historic moment, and nobody should deny this. However, as far as the market is concerned, that may be the most important point: The huge hit to GDP delivered by the coronavirus is already part of history. Even Hubei province is in the process of reopening. Chinese stocks had already taken their lumps on the back of the economic slowdown, and these numbers don't appear to have created a problem for them. Equities in the Chinese mainland and in the rest of emerging Asia were already having a good day when the data were released, and the news did nothing to stem their advance. Chinese A shares and the MSCI Asia Apex index, covering the region excluding Japan, are both now down barely 7% for the year. Given the scale of the blow, that shows startling resilience and confidence from investors:  To some extent, this attitude is reasonable. China has managed to start reopening its economy earlier than many had feared. While the data are undeniably terrible, many forecasters had expected far worse. But it would be as well to be careful. The effect of this hit hadn't finished rippling through China's suppliers and customers before the virus reached western Europe and North America. As counterparts in the West absorb the twin shocks from China and their own measures to combat the coronavirus, that will make life much harder for Asia's largest economy. There are also, of course, risks of a second wave of infections from travelers returning to China. We also need to gauge the psychological effects on Chinese consumers. The country is working its way through a transition to a consumer-led economy, and for the last generation its people have lived with growth that never dipped below 6%, at least according to the official figures. After the Lehman collapse, China's worst quarter saw 6.1% growth. As the country attempts to return to normal, how will they respond to this sudden shrinking? Both their political reaction, and the response with their wallets, will be crucial far beyond China. In this regard, the most disquieting numbers were on retail sales, which dropped by 15.8% in March from a year earlier. This is a huge bite to take out of consumption, and was considerably worse than forecasters had expected:  We know that there were extreme reasons for this. But what exactly will China's consumers do next? Will they feel the need to save more after this experience, or will they gleefully go back to spending? The answer matters across the world, both because it will affect China's recovery, and because it will give us our first clue as to how American and European consumers might behave once they are able to start spending again, a moment that is still a month or so away. Survival Tip Any given activity is more entertaining for children if it can be conducted on a computer screen. This is a sad but apparently unalterable fact of modern life. So, one rather fun educational tool which families can use for free is the Kahoot quiz app. It allows you to build your own quizzes, and provide four multiple-choice answers. You can decorate the questions, and you can open the contests to anyone to whom you have given the PIN. So they provide a way to keep the kids being educated in a way they might actually enjoy, and it makes for a social activity. It's worth a try. Enjoy the weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment