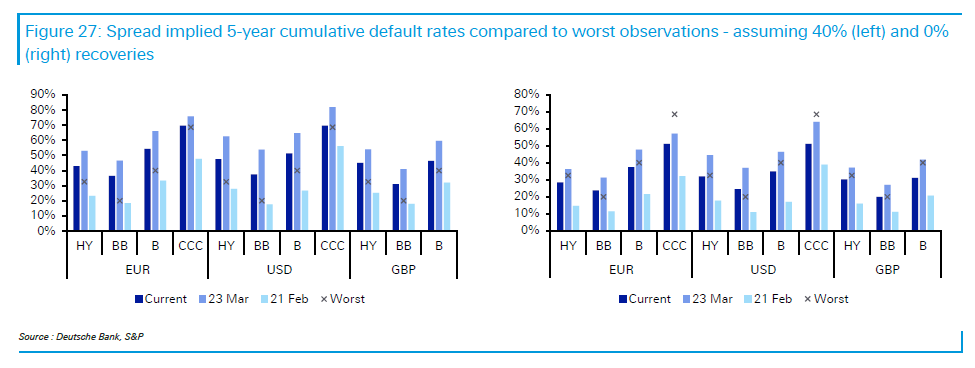

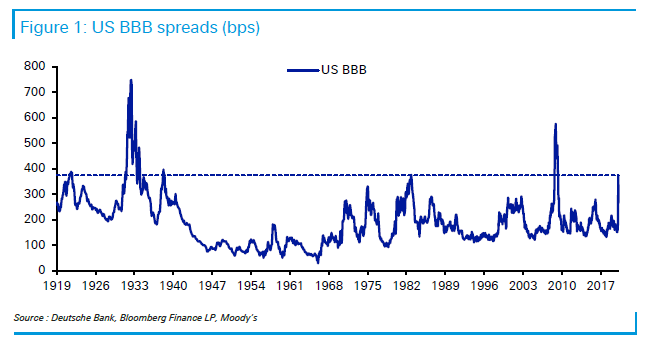

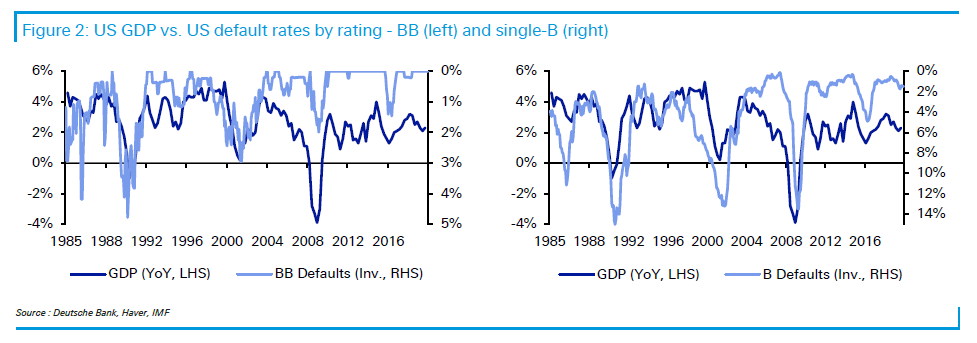

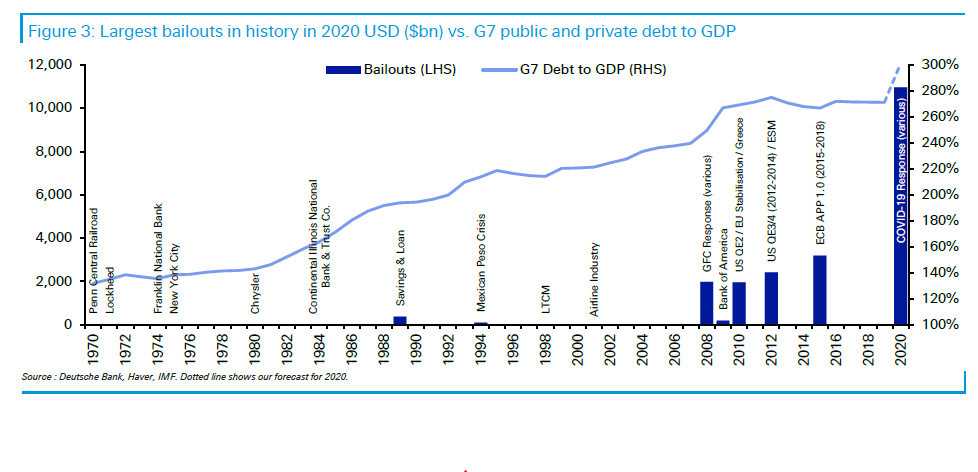

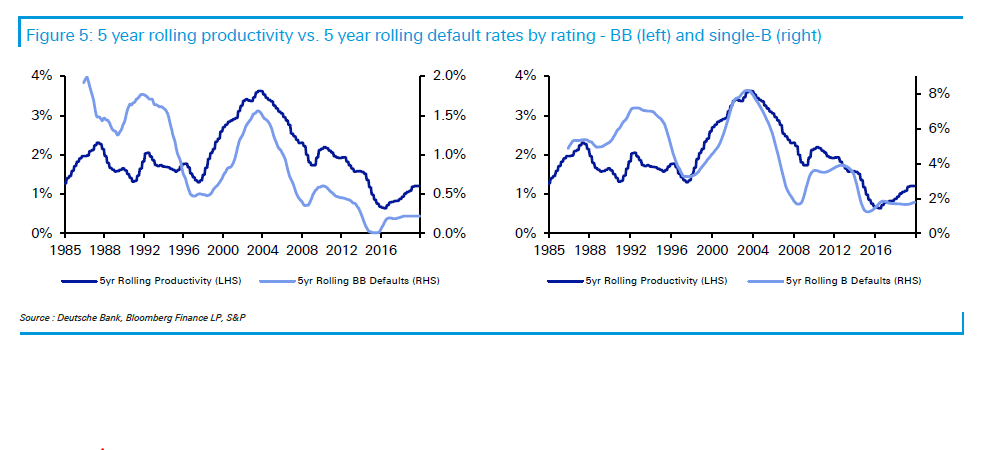

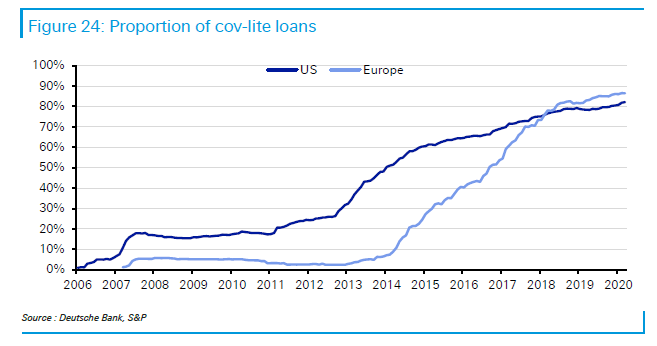

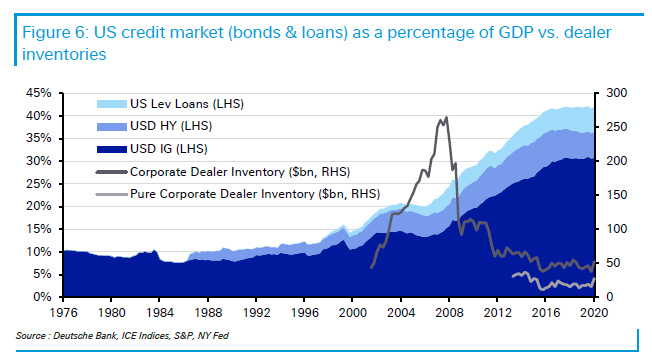

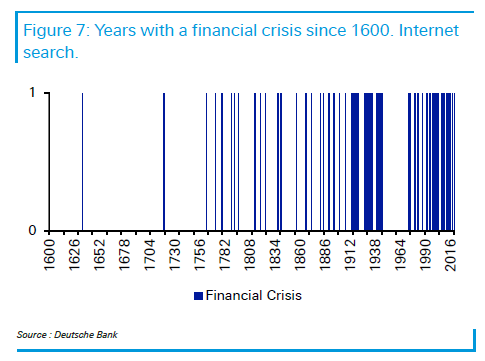

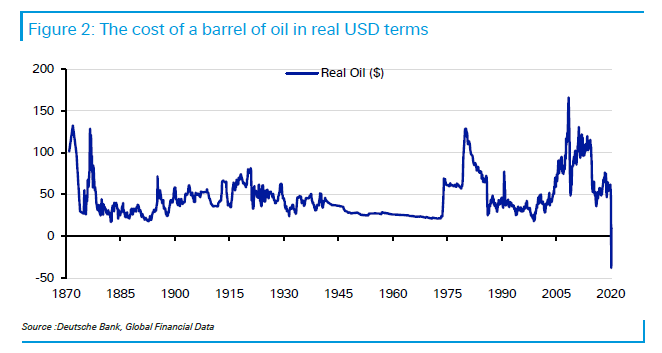

Beelzebub's Telephone Directory One of the most terrifying moments in all of music comes at the end of "The Damnation of Faust," the opera by Berlioz. Faust sells his soul to Mephistopheles, who then takes him on a ride to the abyss, past screaming figures in pain, before he falls before Beelzebub's army of devils. It is thrilling and blood-chilling. And you would think it would be the last piece of music to come to mind when reading the 22nd edition of Deutsche Bank AG' s annual default study. Most normally adjusted people would find this book less interesting than the average telephone directory (if those still exist). At its center is a massive set of calculations to work out what eventual default rate is implied by the spreads at which a huge range of bonds trade compared to the lowest-risk government alternatives. It also draws comparisons over time. In 2007, ahead of the global financial crisis, credit spreads implied that the next five years would see by far the fewest defaults in history. Two years later, they implied that most of the known world was about to go bust. Both times, such extreme results should have been taken as a clear signal that the markets had it wrong. The following charts show the default rates that investors implicitly expected for different grades of euro-, dollar- and sterling-denominated debt on Feb. 21, when the coronavirus was just beginning to attract attention; on March 23, when fear was at a peak; and now. The market was braced in March for a 40% recovery rate on defaulted bonds, the worst on record. They are much more positive now, but still braced for significantly more defaults than they were two months ago:  If we take U.S. BBB-rated bonds, for which there is a long history, we see that credit risk is still perceived to be historically elevated. Outside of 2008 and the Great Depression, it has never been higher:  Where do Faust and his bargain with the devil come in? There is evidence that without desperate intervention, the world would be about to face defaults on a true Depression-era scale. And Jim Reid, the Deutsche Bank investment strategist who has overseen this mammoth project since inception, makes clear that this could turn out to be a Faustian bargain. For evidence, look first at the link between default rates and the depth of recessions in the U.S. As contractions have deepened over time, the defaults they have caused have become shallower, despite the impressive widening of credit markets. For BB-rated credits, the Great Recession was much milder than those of the early 1990s and the 2000s, even though those slumps saw a much smaller hit to GDP:  It would be nice if this were because of the invisible hand of the market, with companies husbanding resources ever better and allocating capital only to the most creditworthy businesses. Sadly, the evidence is that this is largely down to the all-too-visible hand of the government. This chart shows bailouts since 1970, covering essentially the entire period of the post-Bretton Woods global orders. Bailouts are shown in real terms. On the face of it, we are able to sustain far more private debt to GDP than we were 50 years ago because taxpayers are prepared to do far more to prevent defaults:  It would be ridiculous to oppose all bailouts at all times. If the U.S. government had intervened to cushion the blow of the declining economy in 1930 and 1931 it is at least possible that there would never have been a "Great Depression." And it would be very unfair to the generation of people in the prime of their lives now to decide that this was the point to allow much of the corporate establishment to go bust. There is a need for some basic humanity. But each successive bailout seems to be bigger than the one that preceded it, while the relationship between productivity and default rates is very interesting. The positive side to defaults, if there is one, is that it stops inefficient businesses from draining capital, and allows banks and investors to look for projects that have a better chance to grow. An environment with ever lower rates and predictable intervention to avert defaults is also an environment in which we might expect productivity to endure a steady decline. And Reid's numbers suggest that that is exactly what has happened:  The great saving grace of capitalism, its often cruel efficiency, is steadily being lost. But the putative virtue of socialism, that it at least ensures some degree of social justice, grows further away than ever. It is at about this point that I begin to hear Mephistopheles urging on Faust's stallion as they gallop towards the abyss. The singing of the devil's demons gets louder when we look at what has happened to credit quality. The proportion of loans that are "covenant-lite" has exploded in the last decade, even though the crisis should have gives such credit an enduring bad reputation:  In that decade the volume of dollar-denominated has more than doubled, to satisfy the appetite for yield created by the background of virtual zero interest rates. This has happened even though the inventories of big banks that make markets in bonds have collapsed to levels last seen almost 20 years before the crisis, largely as a result of banking re-regulation:  With ever more debt, on ever sketchier terms, against the backdrop of a lackluster economy, it should be no surprise that financial crises are growing more common. This is Deutsche Bank's estimation of the incidences of financial crises since 1600. The definitions may well be questionable, but they are doubtless correct that the era of the two world wars and the Depression saw the heaviest concentration of financial crises in history:  The chart also shows that crises have intensified in recent years. But what sticks out like a sore thumb is the period from the war until about 1970, when Deutsche Bank recorded no financial crises at all. This of course overlaps directly with the Bretton Woods era of exchange rates fixed to the dollar, which was fixed to gold, and heavily regulated banking. If this chart looks familiar, compare it with another from Jim Reid that I reprinted last week. This is the oil price in real terms going back to 1870, and again the Bretton Woods period sticks out like a sore thumb as an island of stability:  I don't want to rhapsodize Bretton Woods, which itself had many Faustian aspects. It only managed to last a quarter-century, and in effect covered a small chunk of the world. The communist bloc, and the global south, were excluded. Starting with the impulse provided by post-war reconstruction helped. It also relied to an extent on financial repression. Until 1951, the Federal Reserve was under orders to keep bond yields down and effectively force everyone to lend to the government at a cheap rate. With timing that cannot be coincidental, the New York Fed published this paper on how financial repression worked earlier this month. As it stands, the ride toward the abyss is bringing an ever more sluggish economy and an ever deeper sense of injustice in its wake. How might this end other than with capitalists confronting the devils they most fear? Reid suggests the most likely conclusions are either financial repression, or a dose of inflation. And as nobody in the markets is positioned for inflation at present, that might just be the position of maximum pain. Survival Tips One great way to maintain your sanity as the Covid-19 cabin fever intensifies is to adapt the lyrics of well-known songs to the coronavirus. Thee are a lot of creative people out there who have had the imagination and the talent to put together their own spoof versions during the lockdown. And as revered a figure as Ed Yardeni, the veteran market analyst, has saved himself from cabin fever by putting together a big list of the best ones, which you can find here on LinkedIn. Did the Kinks or the Knack ever think about the possibility that it would be easy to substitute the name "Corona" when they wrote songs to Lola and Sharona? Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment