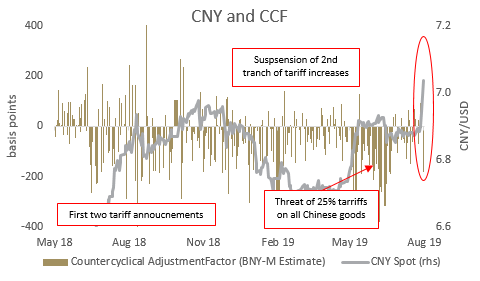

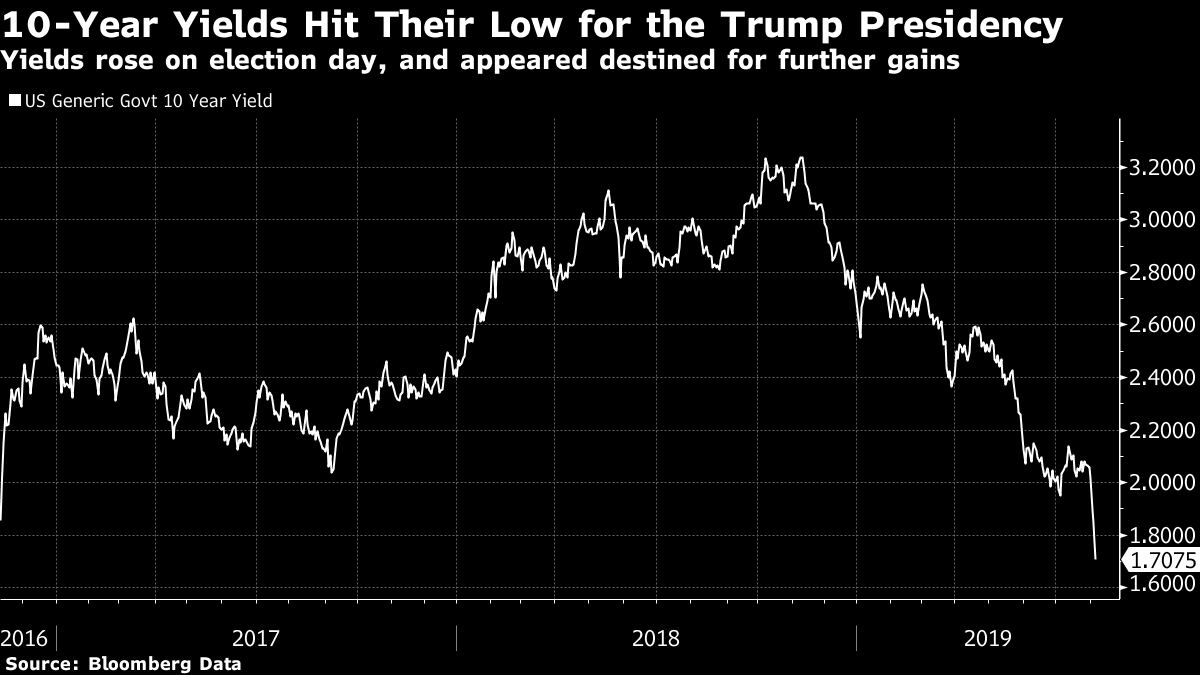

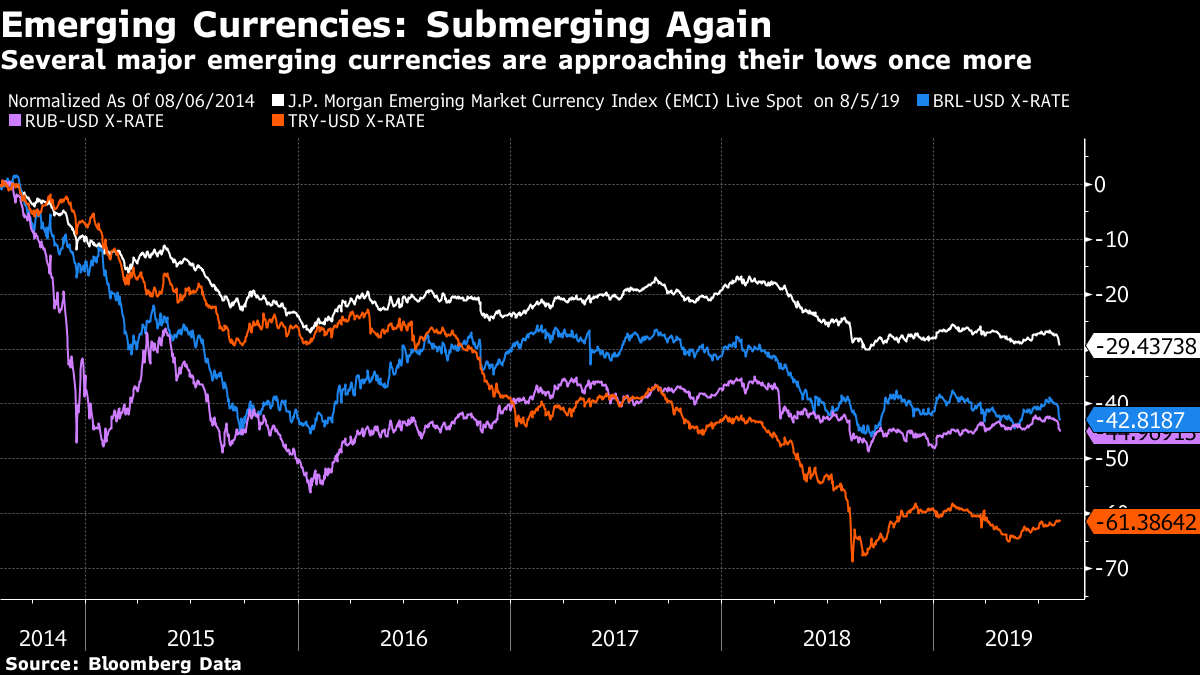

| As far as financial markets are concerned, the trade war has finally broken out. Barely a week ago, on July 26, after more than a year of vocal hostilities, the S&P 500 Index was at a record high. Although much discussed, the trade conflagration had little impact on markets, and little damage was priced in. Working on game theory, investors noted – correctly – that some of President Donald Trump's greatest threats of 25% tariffs had never come to fruition and that both sides had an interest in reaching a deal. The last three trading days have seen traders jettison that logic. While they are not certain that there will bea seriously damaging conflict (which would also include friction over currencies and over regulation of technology) investors have begun to price in a significant risk of such a thing. This was sudden and dramatic, and perhaps best caught by the remarkable outperformance of the most popular exchange-traded funds owning long bonds, while the most popular S&P 500 ETF languished:  Was this justified, and should we expect a continuation? The answer to the first question must be "yes." For many months, the narrative coming from the White House had been that some kind of a deal with China would be forthcoming. Both sides had aimed to ease tensions in public, and markets had priced a virtual certainty that a harmless deal would be reached. This was a questionable judgment. No tariffs imposed by either side have at any point been removed once they had started, so the detente is not obvious. But the judgment was clear. Last week's presidential tweet announcing a new round of tariffs was thus a total shock and suggested that the ruling case had to be jettisoned. Then came China's move to allow the yuan to weaken beyond 7 per dollar for the first time in more than a decade. Seven is merely a round number, of course, but it had been endowed with some importance. The Chinese authorities had plainly been trying to keep the exchange rate below 7 per dollar in recent years, and over the last few months this became an important sign of good will in the trade dispute. This latest move beyond 7 should therefore be taken as a clear sign that good will has been withdrawn:  It is almost exactly four years since a clumsily handled devaluation of the yuan in mid-2015 caused a global sell-off. That was a mistake. This time, the Chinese authorities unmistakably knew what they were doing, and said so. This devaluation evidently counteracts some of the effect of U.S. tariffs, so it is obviously a step in the trade conflagration at the very least. Trump responded with a tweet alleging "currency manipulation." By any common sense definition, China has been manipulating its currency for many years. But the phrase has specific resonance for foreign-exchange traders. If the U.S. Treasury names another country a manipulator, it is then statutorily required to spend a year in negotiations over the issue, backed by the possibility of sanctions. And indeed, once the markets had closed, the announcement came that China had indeed been declared a "currency manipulator" in yet another escalation. This escalation, like the yuan's move through the 7 barrier, can be overstated. It is questionable whether any of the Treasury's sanctions would go beyond what is already proposed for China, given that tariffs are already on the agenda. It can, for example, stop the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corp., a government development agency, from financing any programs in China but it was not doing so in any case. Also,it seems absurdly late in the day to call China a manipulator. China manipulated its currency lower for many years. Now, with the gap between Chinese and U.S. interest rates far narrower than it used to be, it had been entering the market to keep the currency stronger, rather than weaker:  Moving the currency beyond 7, then, was not difficult. It merely involved letting the market do what it wanted to do. It also does not prove that China is now bent on deliberate competitive devaluation, which would be far harder and far more provocative. But it can, very significantly, be seen as a retaliation, a withdrawal of good will and a warning shot. Indeed, this chart from Bank of New York Mellon's foreign-exchange team suggests that China even intervened to stop its currency from falling even further:  In this chart, the CCF is the "Countercyclical Adjustment Factor," which is the measure used by the Chinese authorities when deciding how much to intervene. When the bar is below the line, it means they have intervened to keep the currency stronger – which happened a lot in the wake of the threats of tariffs last year. On this basis, it appears that China intervened quite significantly to stop the currency from weakening even further. So both sides have taken action to escalate and neither has shown weakness. But neither has yet taken measures that rule out any reconciliation, and the latest escalations have been more symbolic than anything else. What does game theory suggest should come next? Here there is a critical difference between China President Xi Jinping and Trump. One is president for life, while the other needs to be re-elected in a little over a year. This gives Xi an advantage. The protests in Hong Kong also give him a huge incentive not to show weakness. Hong Kong matters, and it makes it even harder for him even to appear to compromise toward western interests. Meanwhile, Trump will likely make the strong economy a central plank of his re-election campaign, and could do without the problems that would follow a worsening trade conflict. He, like Xi, would badly prefer not to look weak, but he has an election to win. That said, Trump has a relatively robust economy behind him, and a central bank with the fire power to add stimulus. He also has the ability to push them to use that fire power by talking up the trade war. China's leadership desperately needs to keep delivering economic growth, and it is in the middle of a difficult deleveraging. So some of the logic that seemed so clear to investors a week ago remains in place. There is a logic behind escalation at present, but there is still ample incentive for both sides to calm things down. What effect should this have for investors? Within the U.S., the most clear effect is that at a number of levels the big boost administered to risk appetite by Trump's election victory in November 2016 has disappeared. For example, look at the copper/gold ratio. When copper is outstripping gold, that is taken as a sign of confidence. But as of today, for the first time, gold has outperformed copper for the Trump presidency:  Or we could take a look at bonds. The benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury yield is now lower than it was on election day for the first time:  That the stock market had its worst day of the year on Monday even as bond yields tanked shows that risk sentiment has been very seriously hit. The negativity is also startling given the great confidence that more interest-rate cuts from the Fed are on the way. The shift in Fed sentiment is quite startling. For example, the odds of a 50-basis-point cut next month have risen over the last three trading days from 1% to 44%. The odds that the target federal funds rate will be below 1% by election day next year have also risen from a negligible level to 44% – a remarkable development within three trading days of a determined attempt by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell to talk down the potential for further rate cuts. What lies ahead? Obviously we need to know whether Trump's threatened tariffs take effect as threatened at the end of this month. Words from the Fed could also change things, with another cut next month seen as a total certainty, the central bank is unlikely to do anything to alarm traders even more, but any risks from Fedspeak would be toward sowing concern that rates will not fall on cue. Within markets, one of the greatest risks concerns emerging-market currencies. Most are no longer manipulated,though their finance ministers might want to manipulate them. This means that many have tumbled against the dollar, adding to the risk of an emerging- market crisis. This chart shows the performance of some major emerging currencies over the last five years, along with the broader JPMorgan EM Foreign Exchange index. In all cases, they remain above their lows, but appear to be heading to retest them:  This is not encouraging. Where are the opportunities? With markets now priced for an imminent recession, those with a little courage might care to bet on growth, through buying cyclical stocks or emerging markets – assuming they believe that recessionary fears are overdone. If you expect the imposition of tariffs at the end of this month, with further escalations thereafter, then the market is still not remotely attractive. The major U.S. stock markets remain above their long-term 200-day moving averages, for example. Bonds would be attractive if the trade situation works out this badly – but they start very expensive so the opportunities for gains are not great. Precious metals also make evident sense, even with gold at a six-year high; anything that would not be directly hit by the trade conflict grows attractive. But the greatest issue is that so much still turns on the next move in the trade conflict, and to predict that move you have to predict the internal workings of Trump's mind. So whatever any investor does, they should best stay balanced. A note for your calendar. It is only natural that we view the world in terms of calendar years. But at present this is providing us with a distorting view. As many will remember, there was a screeching sell-off in stock markets at the end of last year, which hit bottom on Christmas Eve. That led to correct, but perhaps misleading, comments, such as that this was the strongest year for the U.S. stock market since 1997. While true, this ignored the fact that a sell-off had created a great buying opportunity just as the calendar turned. Rather than emphasize that the S&P 500 was at one point up more than 20% for the year, I think it better to stress that U.S. stocks have made no progress at all since the rally that followed the big corporation tax ended in January 2016, while the rest of the world has sunk into a bear market. This is what stock markets look like if we start on Jan. 26, 2018:  Lest people think I am being a killjoy, note that viewed this way, the opportunities for further gains look very much greater.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment