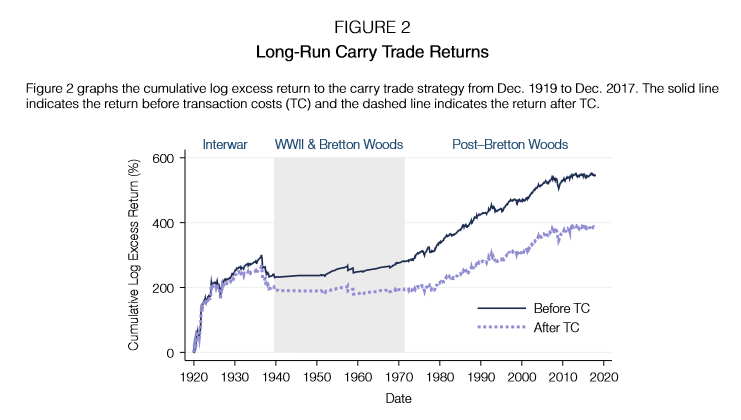

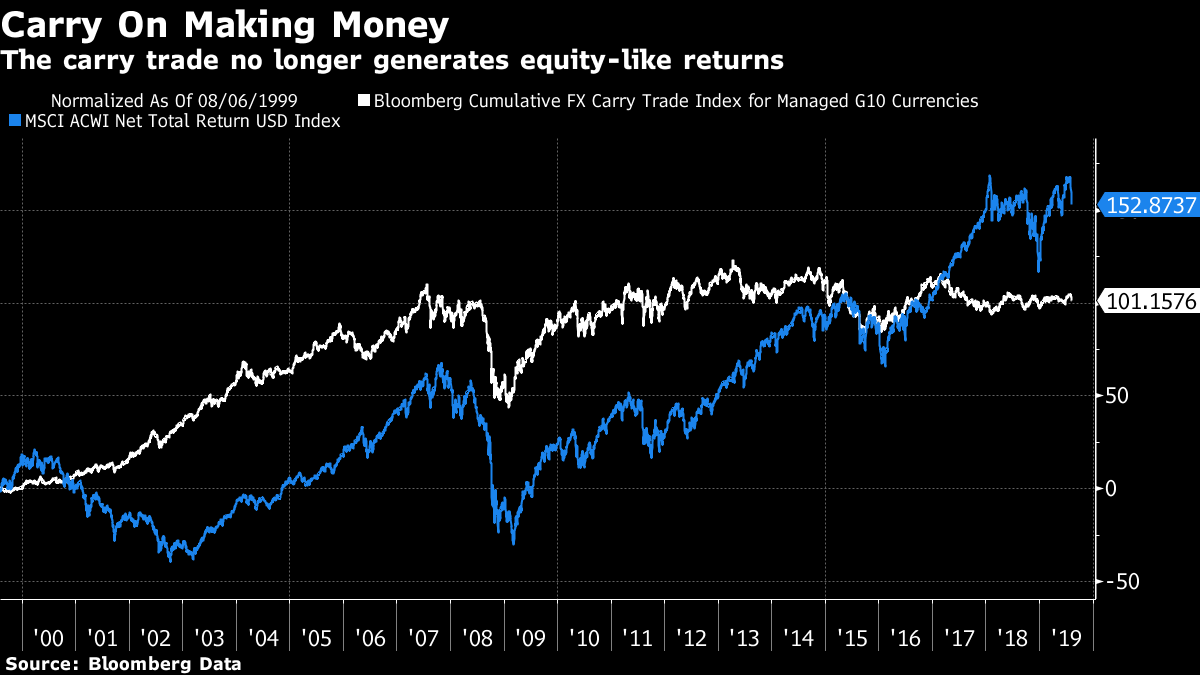

The era of carry. It's no secret that yields on sovereign bonds around the world remain stunningly and historically low. And that, in turn, means a revival in the "carry trade." So it's worth knowing a little more about it so as to both profit and and avert a very real chance of disaster. Carry trading is best known from its incarnation in the foreign-exchange market. It involves borrowing in a currency where interest rates are low and parking that money in a currency with higher rates, pocketing the difference, or "carry." Ideally, you get paid for doing nothing. The primary risk is that the currency in which you borrow starts to appreciate at the expense of the one in which you have put your money. That can generate huge losses in a hurry. One big problem with carry trades is that they become self-fulfilling. Most famous was the yen carry trade, which made big money for investors in the years ahead of the global financial crisis — until it didn't. Typically investors would borrow in yen and put the proceeds in a currency where the economy has dependent on producing commodities and with much higher rates. Think the Australian dollar. This trade was so popular that it actually helped to push the yen lower and the so-called Aussie up, thereby generating profits. Then, as conditions tightened with the onset of the crisis, traders attempted get out of the trade, thereby pushing down the Aussie against the yen, causing many of those profits to be wiped out. In practice, any increase in volatility or perceived risk — which can be nicely proxied by the CBOE Volatility Index, or VIX — spells doom for the carry trade. In the following chart, the VIX is in green and the year-on-year profits on the yen-Aussie carry trade (without including the gains that would have been made by the different interest rates) is in blue. As can be seen, a lot of reliable money suddenly disappeared when volatility shot up:  Logically, if rates are often negative, then carry becomes very attractive. You are being paid to fund the trade with a negative-yielding currency. The point is to find something that will safely offer a positive yield. That has meant some more exotic versions of the carry trade. Here is the same exercise, this time with the VIX in green and the exchange rate between the Indonesian rupiah and the yen in blue, starting on U.S. election day in 2016:  The year 2017 proved to be one of phenomenally low volatility, and phenomenally high returns for carry trades. That changed when volatility returned last year. And in the last few days we have seen a nasty little "carry crash" as volatility spiked with the intensification of the trade war. Carry trading is a sensible strategy when you are being paid to borrow, but if too many people try to do it, the impact of further spikes in volatility could be alarming. Handily, two interesting studies of the carry trade are at hand. First, within the currency space, a group of academics look at a century of carry trading ("Currency Regimes and the Carry Trade" by Olivier Accominotti, Jason Cen, David Chambers and Ian W. Marsh). This reveals that a strategy of borrowing in low-yielding currencies and parking the proceeds in the three-month bonds of higher yielding currencies has worked out over the long term. The Bretton Woods era, however, when currencies were effectively pegged against the dollar, essentially eliminated profits from the trade, suggesting that the appreciation that generally comes from higher-yielding currencies is important to returns. The graph below shows returns before and after transaction costs.  Obviously, there was much more money to be made in the hectic 1920s, but it was also a very respectable trade for many years after President Richard Nixon effectively ended Bretton Woods in the early 1970s. In the last few years, however, despite remarkably low rates in some countries, it has been rather less a fount of profits. This chart compares the total return made on Bloomberg's cumulative index of carry trades between major currencies with the total return on MSCI's All-World stock index. The two were surprisingly competitive until recently, showing why the carry trade has been so popular:  The problem is that the carry trade tends to make money reliably for a while, and then it suddenly doesn't. This generally happens when governments decide to alter a peg at which their currencies are trading. Trading with politicians as a counterparty is always dangerous. Meanwhile, a forthcoming book by Tim Lee of pi Economics in Connecticut, Jamie Lee and Kevin Coldiron of the University of California at Berkeley titled "The Rise of Carry" will argue that carry trades have grown very dangerous. Lee argues that "carry in financial markets — which is associated with liquidity provision — is a financial manifestation of power. Central bank moral hazard-creating policies have supercharged carry to create a pattern of long expansions of carry trades interspersed with dramatic crashes; carry crashes." Carry trades have also moved beyond foreign-exchange markets. The Credit Suisse Carry Income Index, which backs various structured products, includes indexes covering foreign-exchange, commodities, interest rates and emerging markets. It has had a tough time of late:  Lee makes clear that he thinks the situation is dangerous: "Carry trades have four crucial features: leverage, liquidity provision, short exposure to volatility and a saw-tooth pattern of returns, meaning that a total return index of a carry position ratchets upwards for extended periods but suffers occasional very large losses. Currency carry has performed much less well over recent years. But we explain in the book that carry overall can be expanding even as certain carry trades may contract or crash. At the center of the global financial market structure is a single global volatility risk factor, which is best represented by the VIX. The S&P 500 itself has become the central carry trade. As long as the VIX remains suppressed the global carry bubble is expanding." It is hard to dispute. During the financial crisis, many disparate indexes came to look identical to each other, and to move in accordance with ups and downs in the VIX, because investors had effectively made the same bet many times over in different asset classes. The same behavior is occurring again, although it may not be as obvious because the investments that might make a destination for carry traders are widely spread and go beyond foreign exchange. Carry trading, or at least a version of it, is made easier by derivatives allowing investors to place bets on the level of volatility. Carry trading, Lee says, is associated with the growth of both liquidity and debt. The ultimate concern, once a carry bubble bursts, should be deflation. This is because the value of assets, pumped up by cheap leverage during the carry period, suddenly declines. And, of course, deflation followed the carry crash during the global financial crisis. Its effects were masked by the huge growth in asset prices that followed, but much of the world is in a deflationary environment. As Lee says: Extreme leverage and debt contain within them the risk — ultimately the certainty — of deflation. As long as the carry bubble goes on, deflation is held at bay. During the expansion misallocation of resources is associated with growing GDP, albeit at an unspectacular pace because trend growth is declining. When the carry crash occurs, the cumulative misallocation of resources is revealed. The business cycle resembles the pattern of the total return index of a carry trade. This is a gloomy take on the issue. And it is hard to argue against engaging in some version of a carry trade. With conditions as they currently are, and much money available for negative interest rates, the logic for carry trading is obvious — and so therefore is the risk that asset prices will become bloated by carry trades until the total amount of leverage is unsustainable. At the very least, it behooves everyone to watch for signs that carry trades are growing unsustainable, and to grasp that much is riding on what appears to be artificially low volatility. And as for the various politicians currently stepping up rhetoric that will in turn fire up volatility, they should know that they are playing a dangerous game. So as long as volatility stays controlled, carry traders can carry on, carry on, like nothing really matters. Once investors grow skittish, carry traders lose money.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment