Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's hoping someone, someday will love it as much as investors currently love safe debt. --Luke Kawa, Cross-Asset Reporter

Indebted Investors

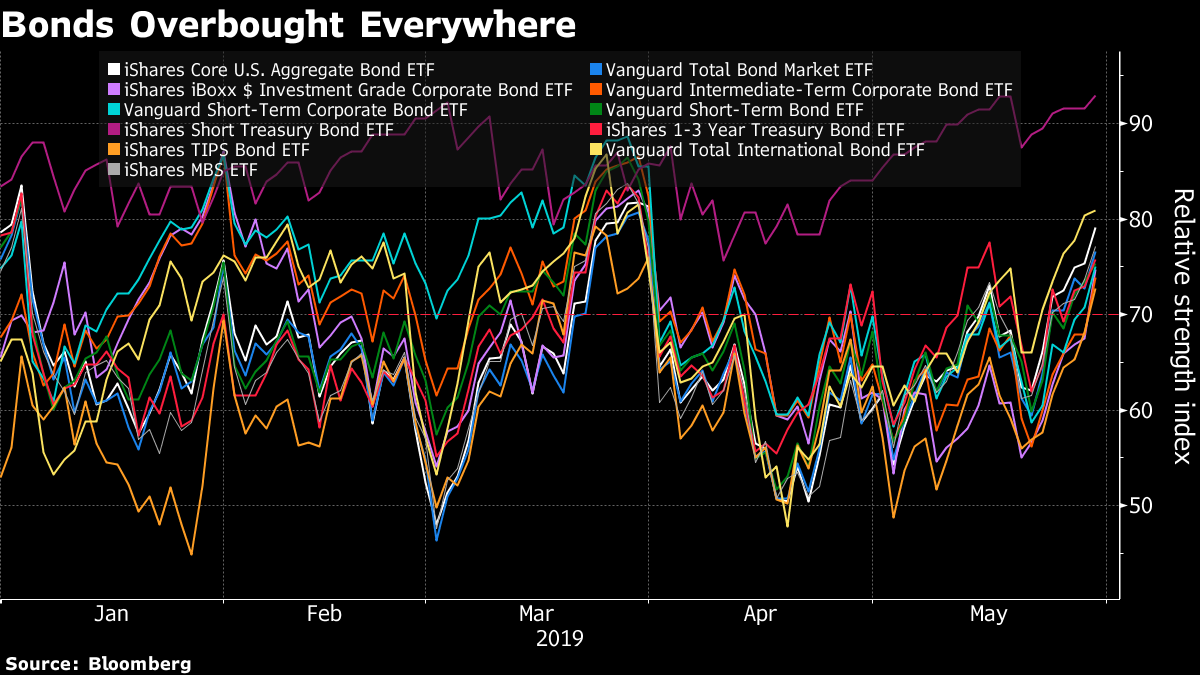

There's a strong stench of B.O. in the market: bonds, overbought.

Just how much of a shining have investors taken to debt this month? Well, let's take a peek at the 11 biggest U.S. exchange-traded fixed income funds, which have almost $300 billion in assets altogether.

AGG – BlackRock's aggregate U.S. bond market fund? Overbought.

BND – Vanguard's similar offering? Overbought.

LQD – a high-grade bond fund? Overbought.

VCIT – intermediate high-grade bonds? Overbought.

VCSH – short-term investment grade debt? Overbought.

BSV – short-term U.S. debt? Overbought.

SHV – short-term Treasuries? Overbought.

SHY – 1 to 3-year Treasuries? Overbought.

TIP – inflation-protected Treasuries? Overbought.

BNDX – international bonds? Overbought.

MBB – mortgage-backed securities? Overbought.

That's right, all of these disparate components of the fixed-income universe are technically overbought, according to the 14-day relative strength index, a gauge of the momentum and persistence of price movements.

The strength of the eye-popping global sovereign bond rally has some searching for reasons why it's due to come to an end – especially in its epicenter, U.S. Treasuries.

Some of the catalysts proffered:

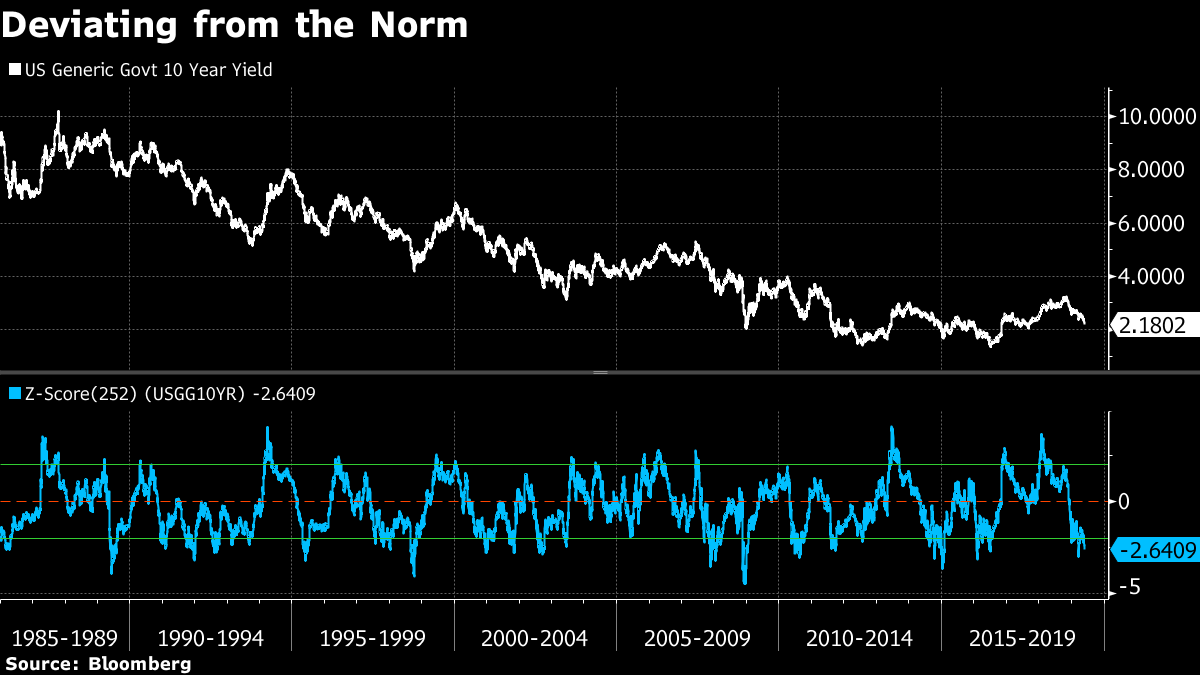

In a nod to these technicals, Bespoke Investment Group observes that the 10-year yield is oh-so-stretched, trading more than two standard deviations below its one-year average.

Aberdeen thinks USTs are a sell because the Fed won't be as willing to cut as much or as soon as market participants anticipate.

Demand at auctions (including this Wednesday's) hasn't always been stellar.

The wind-down of short-volatility trades in Treasuries could remove some of the fuel from the bond rally.

But there's also cause to suspect the fund managers musing about a 2% 10-year yield aren't blowing smoke. For one, the 10-year yield still trades at a premium to what 31 major investment firms think the federal funds rate will average over the next decade – a survey that was most recently completed before the re-escalation of the trade war, and therefore more likely than not to see an additional move to the downside.

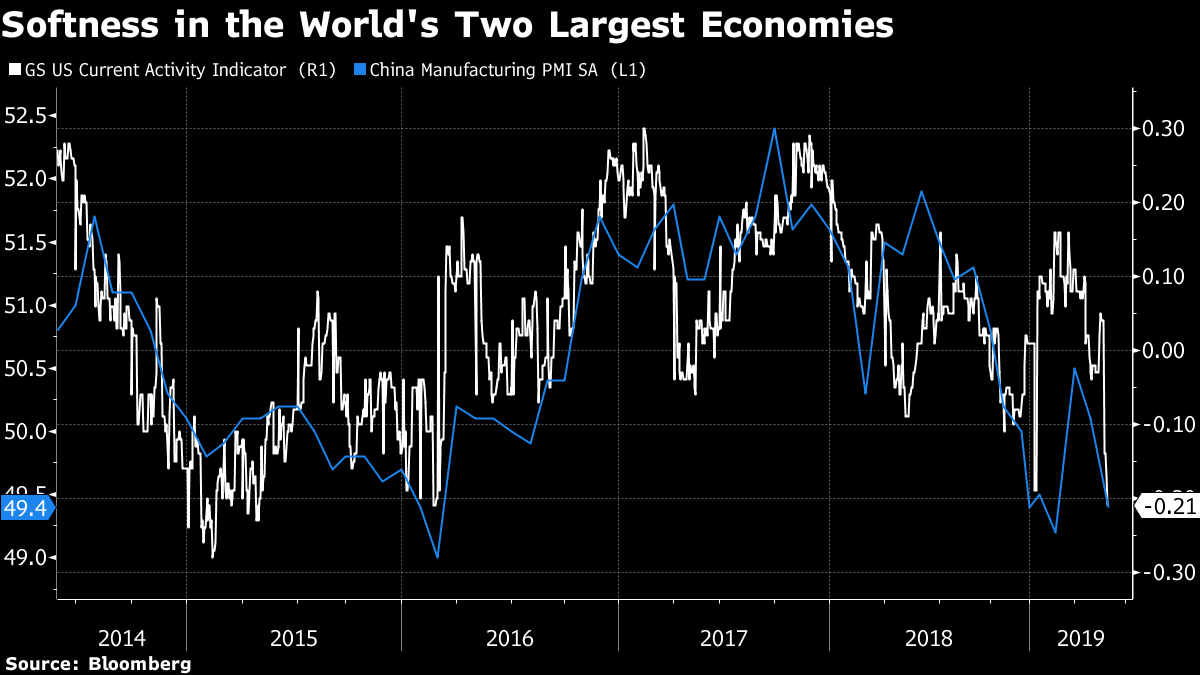

Goldman Sachs' current activity indicator for the U.S. is firmly in negative territory, at its lowest level since 2016. The most recent Chinese manufacturing PMI data also disappointed, pointing to contraction in the sector.

On Thursday, the lackluster outlook for growth saw real rates tumble to their lowest intraday and closing levels since January 2018, posting a much bigger drop than 10-year breakevens even during a session when oil prices cratered.

Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida remains confident the U.S. economy and policy rates are in a good place right now. But unlike Powell, he was at least willing to outline some of the criteria that could elicit a change in the Fed's stance – and those considerations skewed dovish.

"My colleagues and I understand that our responsibility is to conduct a monetary policy that not only is supportive of and consistent with achieving maximum employment and price stability, but also, once achieved, is appropriate, nimble, and consistent with sustaining maximum employment and price stability for as long as possible," he said in a speech. "If the incoming data were to show a persistent shortfall in inflation below our 2 percent objective or were it to indicate that global economic and financial developments present a material downside risk to our baseline outlook, then these are developments that the Committee would take into account in assessing the appropriate stance for monetary policy."

"Nimble" might end up being the new "patient" – it's a word that doesn't commit the central bank to inaction.

Oh, and it's now not just a U.S.-China trade war – a second front has been opened. In a tweet on Thursday, Trump pledged a 5% levy on imported Mexican goods until illegal immigration is resolved to his satisfaction. That curveball pushed the 10-year Treasury yield below 2.2%.

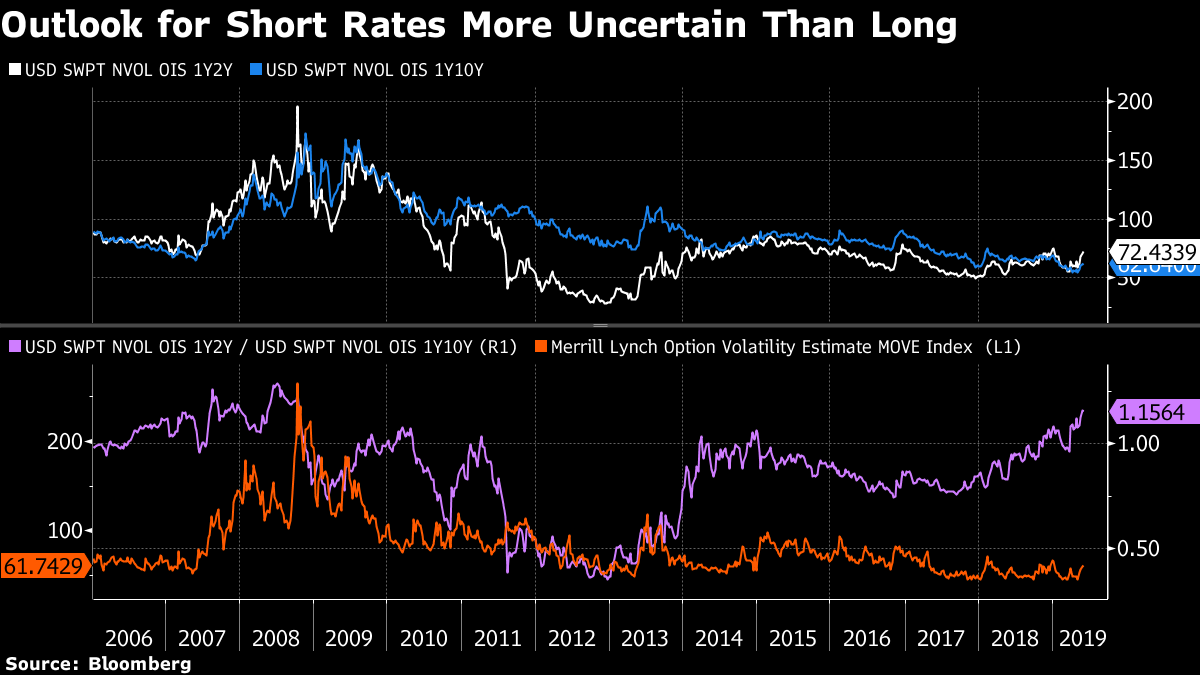

One thing's for sure: the two-front trade war, global economic soft patch, and risk-asset rout have been more than sufficient to re-awaken bond volatility from its slumber and raise recession fears. Among oil, equities, bonds, and credit, Treasuries are the place where implied swings are the most elevated relative to their one-year average.

Interestingly, while the inversion of the 3-month Treasury to the 10-year has deepened, driven by the torrid rally in longer-term debt, the pick-up in bond volatility has been driven primarily by increased uncertainty regarding the front of the curve – that is, just how much easing investors expect the Fed to deliver in the near future. 1y2y swaption volatility is trading at an increasing premium to its 1y10y counterpart.

The bond market is bellowing that an inflection point for the Fed is nigh – it's just a matter of whether the central bank will be proactive or reactive, and how much, and how soon, cuts arrive.

Harley Bassman – inventor of the MOVE Index of bond volatility – sees a particularly ominous, if not imminent, signal of doom emanating from the bond market.

The five-year forward five year swap rate – his preferred curve combination, as it helps control for any effects of central bank bond purchases – trades below the federal funds rate for the first time since the run-up to the financial crisis.

"Well-heeled investment professionals are effectively willing to purchase five-year bonds to be issued in 2024 (five years hence) at a rate below today's risk-free overnight rate," he writes. "I don't know how or when it will resolve, but the yield curve has inverted in a half-dozen places, and eventually this ends in tears."

Safety First

There are many different ways to earn an income; in the real world, reward is not always commensurate with the risk to personal well-being. Typing or executing trades from behind a computer screen, for instance, is considerably safer than working on a construction site. But in financial markets, the relationship between risk and reward is supposed to be more evident – and relative appetite for assets with similar characteristics can tell us a lot about fear, or lack thereof, in the market.

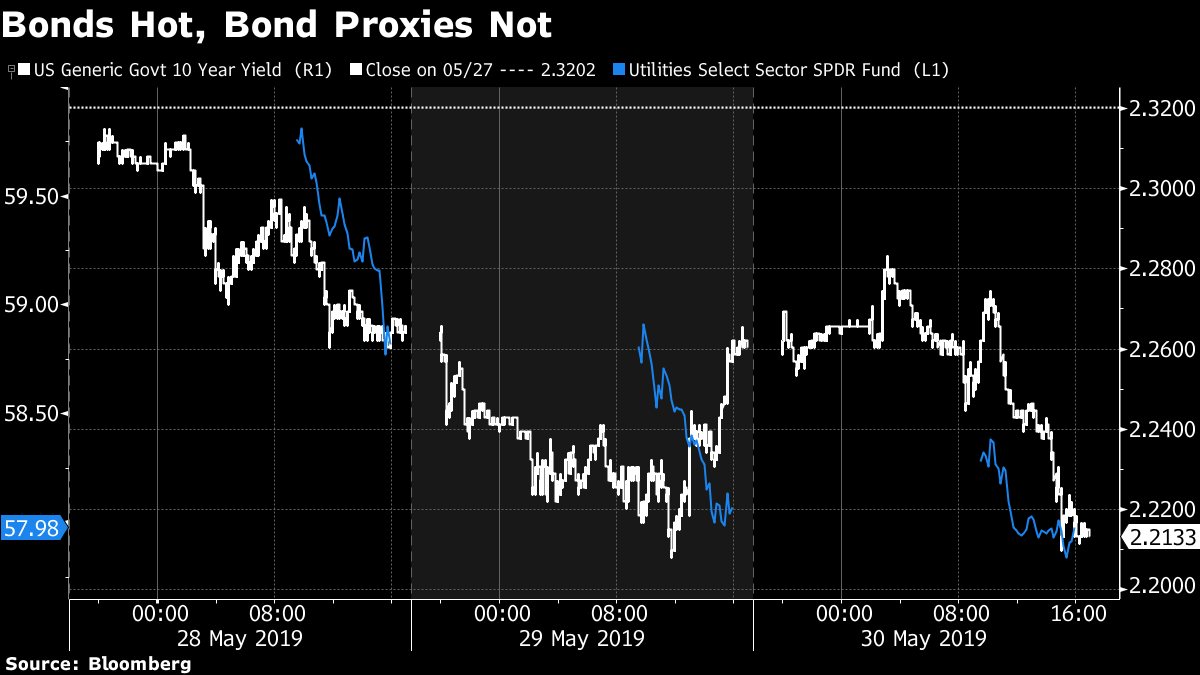

Right now, income-oriented investors prize personal safety to an immense degree. One of the most telling signs of risk aversion this week is that the utilities sector – rate sensitive, with earnings generated domestically – has declined each session this week even as the 10-year yield has retreated.

Investors who buy either bonds or bond proxies are looking for conservative coupons. That the former is in demand while the latter has fallen out of favor suggests that a pervasive mistrust of equities is settling in.

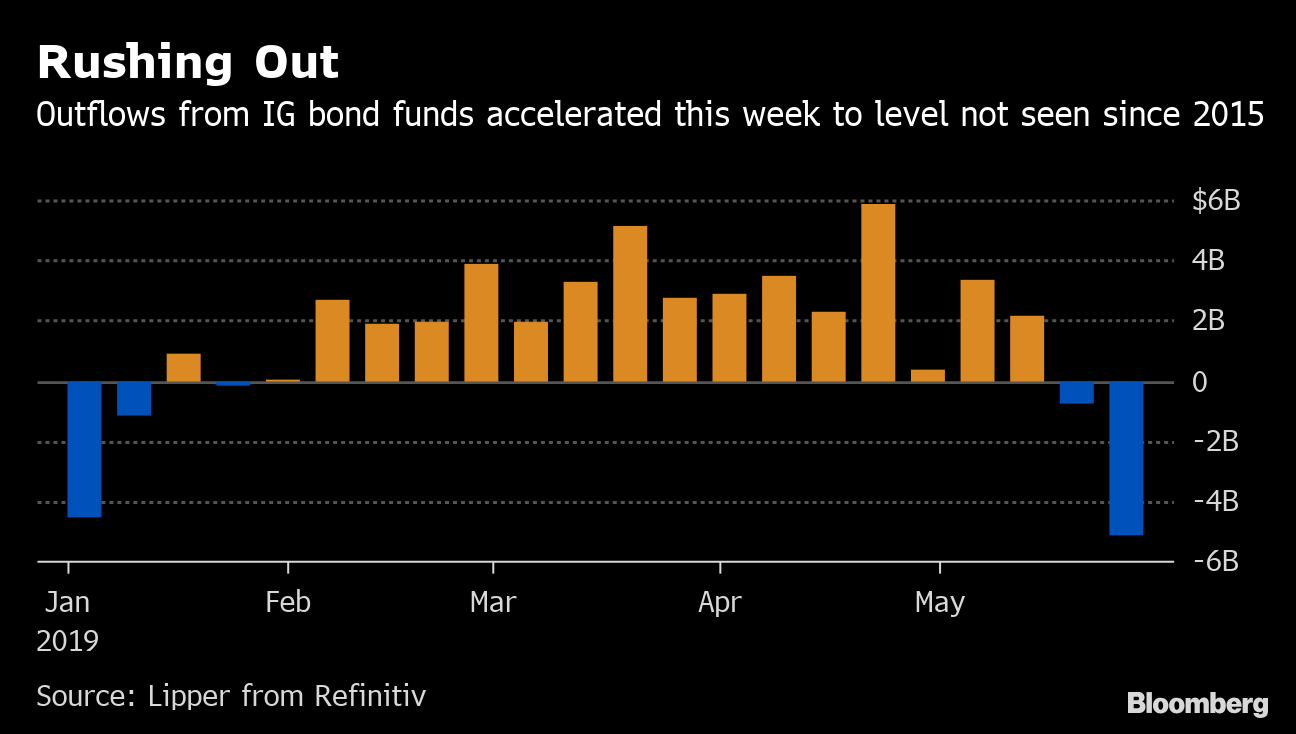

The safety-first mentality is corroborated by the asset class that's in between sovereign bonds and equities on the risk spectrum: credit. Investment-grade bond funds suffered their biggest weekly withdrawal since 2015 for the week ending May 29.

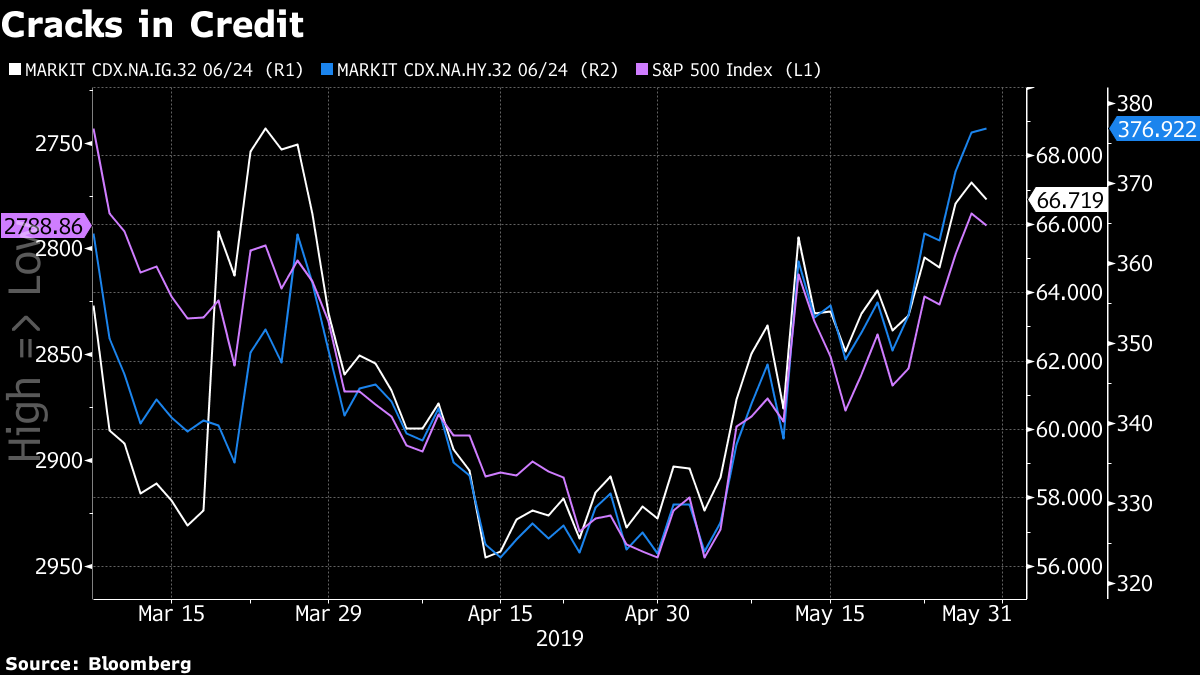

While the S&P 500 remains above its early March intermediate trough, high yield and investment grade credit default swap spreads are wider than they were then.

And the bearish commentary on corporate bonds is swelling to match the outflows.

Scott Mather, PIMCO CIO of U.S. core strategies, calls this "probably the riskiest credit market that we have ever had."

"Current high yield spreads are at the tight end of its 5-year range when yields are this low," adds Citi's Michael Anderson. "Furthermore, if yields fall below 2%, high yield spreads have always been materially wider (typically north of 500bp) in the post-taper-tantrum period."

The bottom line, for now, is that the only income investors seem to want is the risk-free variety.

Post a Comment