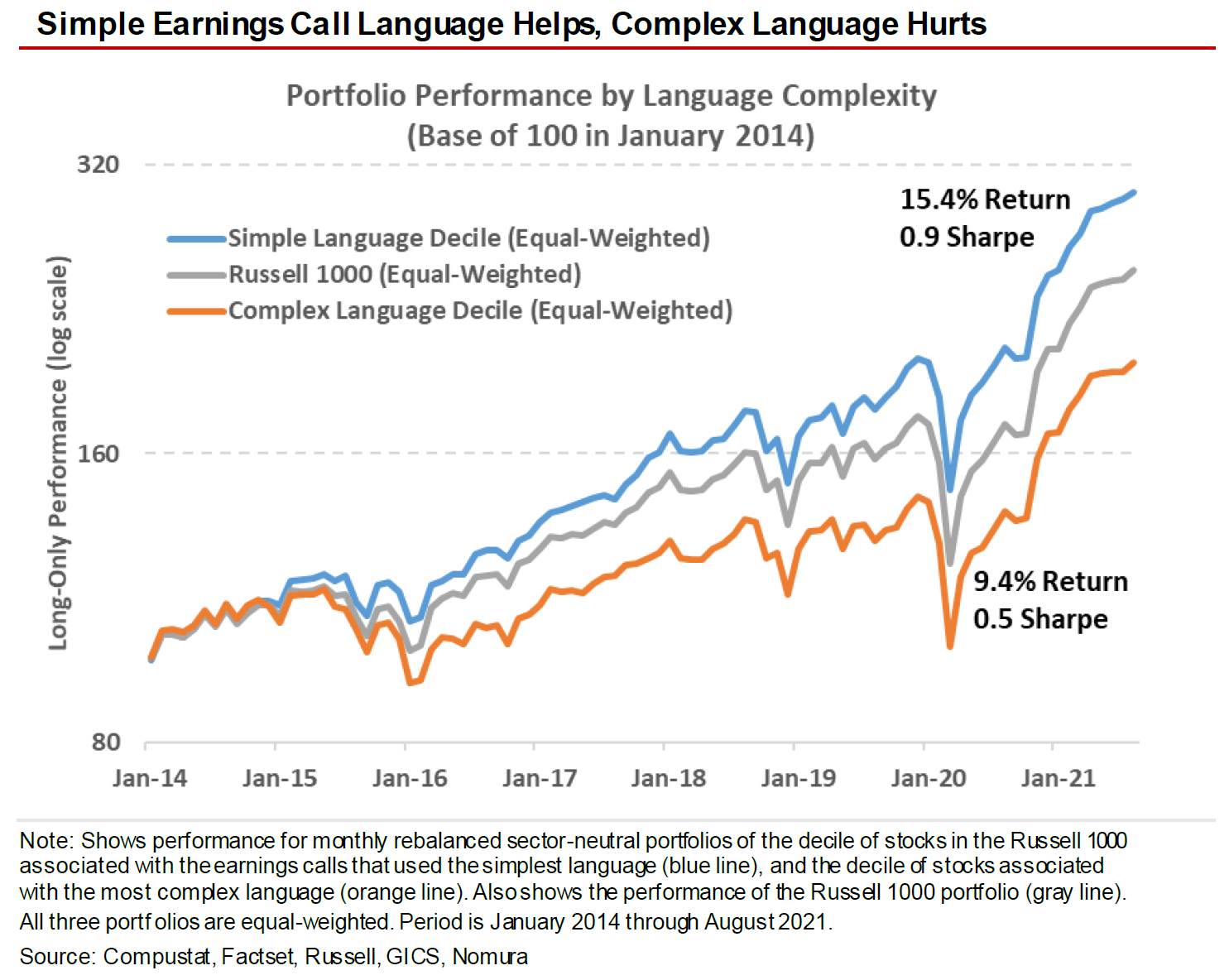

| We're used to crunching numbers in investments. With the improvement in technology to analyze language, Big Data now allows us to start crunching words as well, and it turns out to be very useful. If you want to get someone to invest, make your case in clear language. And for those thinking of investing, if someone pitching to you can't explain their offer in plain speech, that is a sign not to invest. This is the fascinating finding from research by the quants at Nomura Holdings Inc., looking at earnings calls. (The language in 10-Ks is always carefully vetted and written by committee. Such documents tend to be written in bad, complicated prose. But when executives are speaking on a call, they have the liberty to make straightforward points in a simple way.) The results are dramatic. The researchers analyzed the language used by execs in calls for all the companies in the Russell 1000 large-cap index, and split them into 10 groups of 100. Since 2014, the 100 companies whose officers used the most complex language averaged a return of 9.45% per year. The companies in the simplest language decile returned 15.4% per year. The results are robust when controlled for volatility, with the simple language decile having a far higher Sharpe ratio:  What can lie behind this? In part, it's because if you have something to hide you will tend to take refuge in longer words and more convoluted sentences. These will help to hide your meaning. As the trial of Elizabeth Holmes, who ran the failed blood-testing startup Theranos, is in the news, it's instructive to look at this quote from a now infamous profile of her by Ken Auletta for the New Yorker, published in 2014, before the problems with her technology had been revealed: What exactly happens in the machines is treated as a state secret, and Holmes's description of the process was comically vague: "A chemistry is performed so that a chemical reaction occurs and generates a signal from the chemical interaction with the sample, which is translated into a result, which is then reviewed by certified laboratory personnel." She added that, thanks to "miniaturization and automation, we are able to handle these tiny samples."

When people start to waffle like this in earnings calls, then, it should be no surprise when their subsequent share price performance is bad. The converse is true of clarity. Those who know exactly what they want to do are likely to be able to express it clearly, and then do it. None of this applies to the over-lawyered paragraphs in a 10-Ks. As Joseph Mezrich of Nomura puts it: "It is not far-fetched to suppose that spoken earnings calls transmit clearer impressions of important business features like management's clarity of vision than committee-produced 10-Ks." The research calls on the gloriously named Gunning Fog index, which is fully explained here. This index increases with more words of three syllables or more more punctuation marks, and so on. The process produces a number that indicates how many years of formal education a person needs to be able to understand it. The Gunning Fog website has a great feature that allows you to paste in some text and find its index level. Anyone writing a speech might well want to check how they score. To give some examples, I tried a chunk from Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (the hardest piece of philosophy I ever tried to read while at college), and it received a reading of 19.5 (beyond college graduate level); the text of Mr. Tickle, the first of the Mr. Men books by Roger Hargreaves, scores 6.7; and Donald Trump's inaugural address came in at 11.7. Elizabeth Holmes's quote to Ken Auletta scored an astonishing 28. The range of language in earnings calls isn't quite as wide as from Trump to Kant, but it's still wide. According to Mezrich, the 10th percentile of earnings calls corresponded to high school junior level readability (16-year-olds), while the 90th percentile earnings calls correspond to college junior level readability. If your language is as hard to follow as Immanuel Kant's, it's not surprising if people don't buy your stock. This is true no matter how well your company performs. To quote Mezrich: What's astonishing about the results based on the language complexity of earnings calls is that they ignore the content of the management's message. Companies with earnings calls that use simple language produce higher subsequent stock returns than companies with earnings calls that use more complex language, regardless of content. The style in which content is delivered matters.

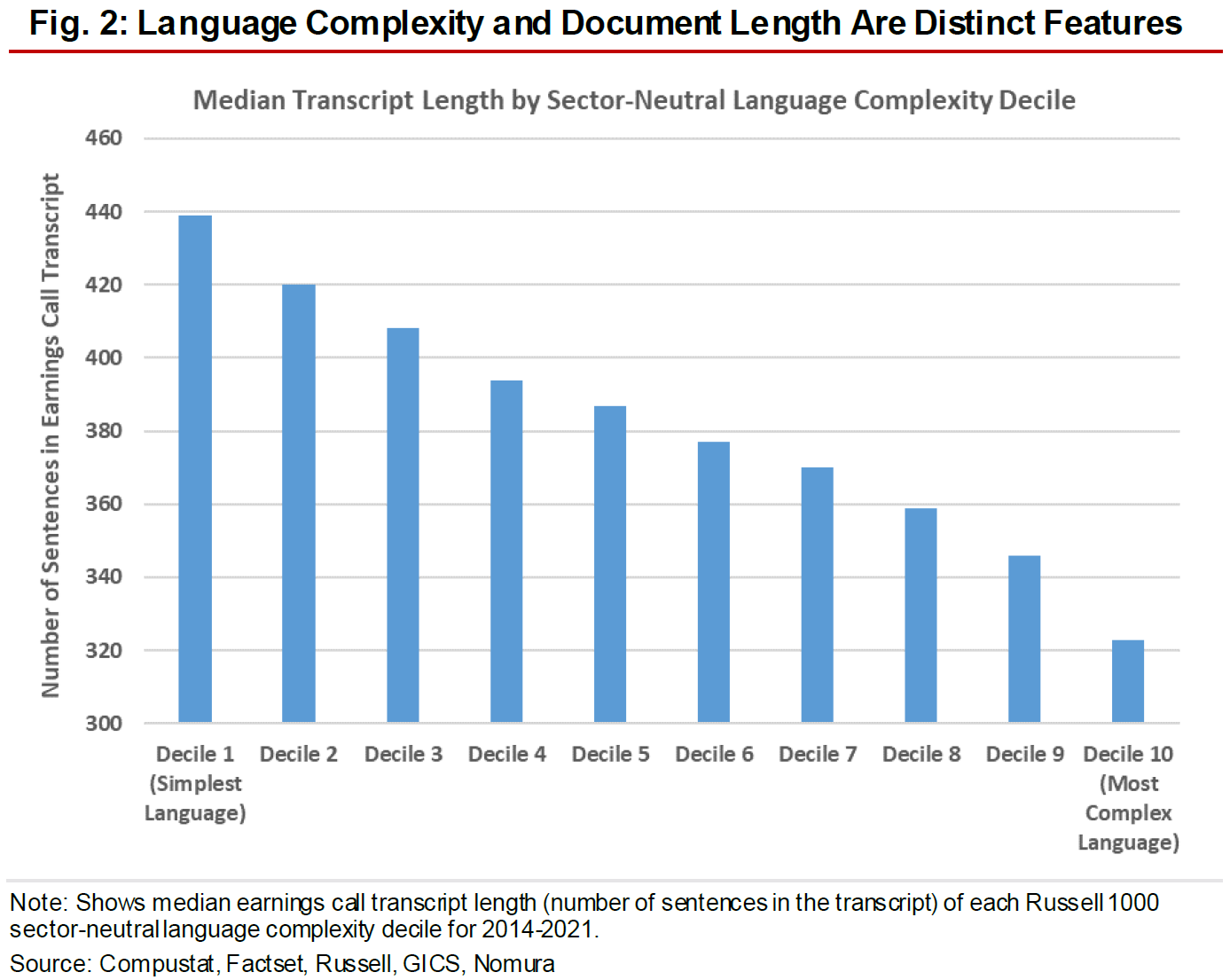

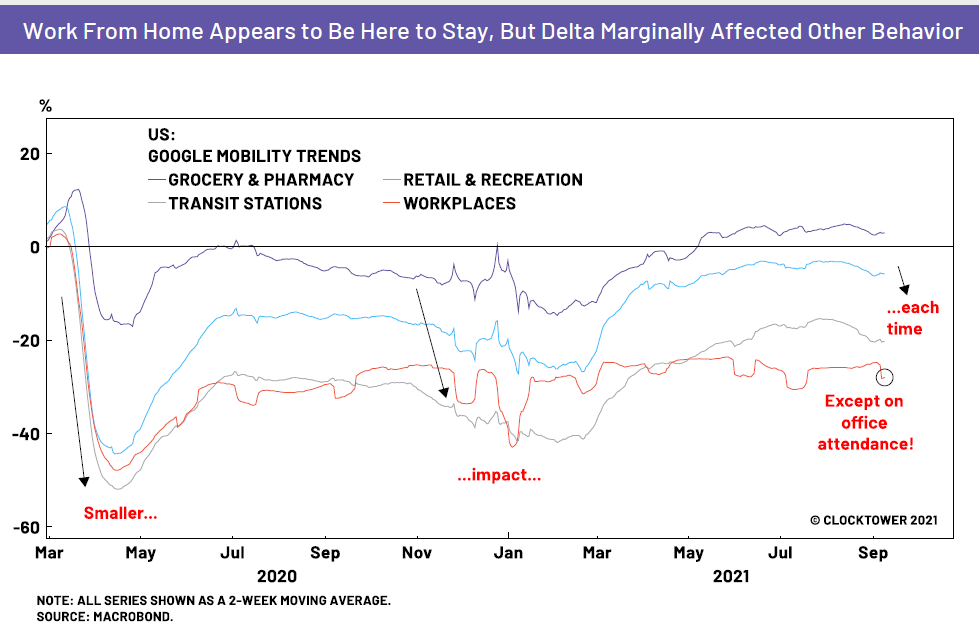

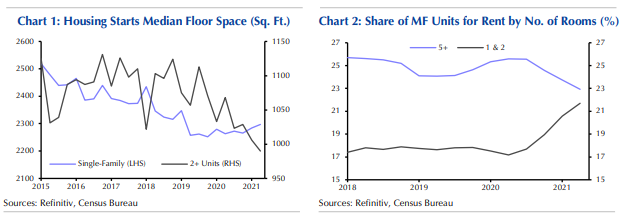

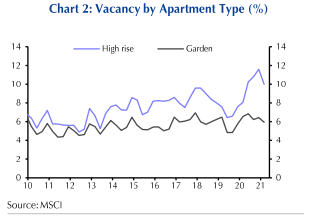

Another point is that while brevity is also good, simple language and brevity don't necessarily go together. Professional jargon develops in large part to enable us to communicate about complex ideas quickly with other people who also understand those ideas. So simpler language tends to go with longer communications, at least in terms of sentences. The relationship is almost perfect:  Brevity is good, and it's hard to achieve. Winston Churchill once apologized for giving a long speech, saying that he hadn't had the time to write a short one. But what is most important is to speak simply. If you take longer to express yourself, but use that time to make yourself clearer, you'll be fine. And if an executive sounds like they're waffling to you, don't touch their stock. This is the month when we all expected to be back at work. The delta variant has clouded that picture, of course. But if we look at the mobility data produced by Google, an interesting picture emerges. It appears that the virus is at this point having a selective impact on our choices of mobility. It isn't stopping us from going shopping or taking our recreation; but it is stopping us from going to work. This graph comes from Marko Papic of Clocktower Group and shows the comparative activity for groceries (back to normal), retail and recreation (nearly back to normal) and workplaces (still far below the pre-pandemic norm):  It's now 18 months since the first dose of speculation that working from home could prove to be habit-forming. It looks like that prediction might just turn out to be true. Even if people and employers aren't deciding that all work can be done from home, it's plain that staying at home for a few days is now regarded as an increasingly valid alternative. That could have obvious ramifications for office space. It's unlikely we will need quite so much of it. The consequences for residential real estate could also be profound, and they've barely started. Capital Economics tried tracking the median floor space of houses as reported to the Census Bureau, and found that housing units have been getting ever smaller, particularly in multi-family blocks. In the second quarter of this year, according to Capital Economics' Matthew Pointon, the median size of a new U.S. apartment dropped below 1,000 square feet for the first time since records began in 1999. If the WFH trend is as durable as it looks, it looks a fair bet that that trend is about to reverse. Such apartments begins to seem uncomfortably small if we now expect to be spending several more days there a week, and want to have comfortable working space there. To back this up, Capital Economics also looked at the Census Bureau's statistics on the share of multi-family units available for rent by number of rooms. This showed a significant increase in the number of one- and two-room apartments still available for rent over the last 12 months, while the number of five-room apartments available has fallen:  Meanwhile, Capital Economics also suggests that high-rise apartments, which tend to be in cities and to be smaller, might be less popular in this environment than garden apartments, which should come into their own when people want to work from home. And indeed, vacancies in high-rises have risen significantly during the period of the pandemic:  It looks as though life is indeed normalizing in the Western world, delta be damned. That will probably mean a recovery on some scale for inner-city real estate. But it does look likely that long-term trends are about to shift. Apartments can't get much smaller, and cities can't get much more overcrowded. Expect WFH to turn those trends around. This week brought the sad news of the death of Grange Calveley, best known as the writer behind the classic BBC animated series from the 1970s, Roobarb. For the uninitiated, the Roobarb theme tune is by a comfortable distance the best TV theme tune of all time (and it had plenty of competition on British children's television in the 1970s). After the theme tune was over, the ensuing five minutes were delightful. Calveley invented a series of stories about a dog called Roobarb and the annoying cat next door, appropriately named Custard. They were wild and weary, in a wobbly animation style, and they were great. I wish they made them like it now. Rest in Peace, Grange Calveley and thank you for lighting up the time between school and tea time. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment