| Discomfiting memories of the 1970s are everywhere. The U.S. administration understandably bridles at comparisons of Kabul to the fall of Saigon in 1975, but the parallels are obvious and painful for Americans (and anyone who dislikes the philosophy for which the Taliban stands). The symbolic significance of the flight of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, just like the images of helicopters airlifting people from the U.S. embassy in Saigon 46 years ago, is probably greater than the practical significance for the rest of the world. It's been obvious for years that the American military adventure in Afghanistan hasn't been a success. But symbols matter. And that brings us to another hugely important moment from the 1970s, when the last tie of the dollar to gold was removed by President Richard Nixon. I wrote an essay on the consequences yesterday. I'd now like to cover some of the main points to have arisen in response. Can there be a return to something like Bretton Woods? It would be very difficult. The Bretton Woods system owed much to the unusual conditions of the postwar world, which aren't going to be repeated. In particular, it started when funds flowed far more slowly than now, and when many countries maintained capital controls. The costs of returning to that, in terms of reduced trade and globalization, would likely be prohibitive. To quote Barry Eichengreen of the University of California, Berkeley: Bretton Woods operated as successfully as it did through 1971 owing to three special circumstances: low international capital mobility, tight financial regulation, and the dominant economic and financial position of the United States and the dollar. There can be no more straightforward an explanation for why nothing like Bretton Woods will be restored in the foreseeable future.

Of these three conditions, tighter financial regulation could be achieved, and might well be a good idea. The rise of China makes it hard for the dollar to maintain its dominance, although the centrality of the U.S. to the global financial system has if anything been enhanced by the departure from Bretton Woods. The emergence of some kind of tripolar world, with growing importance for the European Union and China, is conceivable. There is no particular need for there to be only one reserve currency. But it is unlikely to arrive as the result of an international conference, in a hotel in New Hampshire or anywhere else. Would inflation make a difference?: It might. Nixon thought inflation wasn't a serious political problem, at least compared to unemployment. This was when the only U.S. experience of inflation in living memory had come in brief but brutal doses in the immediate aftermath of the two world wars. Jeff Garten, former dean of the Yale School of Management who earlier this year published Three Days at Camp David about the decision, quotes him as saying: "When you start talking about inflation in the abstract, it is hard for people to understand. But when unemployment goes up one half of one percent, that's dynamite."

Whatever else one says about Nixon, he had good political judgment. He was prepared to take some risk of rising inflation to deal with what he saw as the potentially serious political problem of rising unemployment. A decade later, the first memo produced for Ronald Reagan as he prepared his successful 1980 presidential campaign, started: "By a wide margin the most important issue in the minds of voters today is inflation."

It went on to say that the "public's pessimism" compounded the problem for any presidential candidate, because "they believe that there is little that the president, any president can do about it." The quote comes from America In Search Of Itself by Theodore H. White. Reagan's decisive 1980 campaign was predicated on a determination to deal with inflation. Writing at the time, White made clear that he agreed prices were by far the greatest issue of the day, describing inflation as "the cancer of modern civilization, the leukemia of planning and hope." The tight money policies that Paul Volcker instituted at the Federal Reserve in the early 1980s arguably enabled all that followed. Volcker (appointed by Jimmy Carter though the political credit went to Reagan) couldn't have had the necessary political backing to do this from Nixon, who constantly badgered his Fed chairman for lower rates. A dose of high inflation was necessary. Any shift to some other replacement for or even return to a form of the gold standard cannot happen without a return to inflation first. What would it take to adopt a new system? The answer is another Shock, with a capital S. By taking the rest of the world by surprise, Nixon clarified minds and managed a surprisingly smooth transition. Surprisingly, Garten, whose book is a fascinating blow-by-blow account of the decision, emerged from the exercise with enhanced respect for Nixon. He suggests that unilateral action was unavoidable, and that it actually fostered international cooperation. Then, as now, there was great concern that beggar-thy-neighbor trade policies would result. It didn't happen. As Garten says in the book: There was no effective way to start a multilateral negotiation without Washington's administering a shock in advance. The United States needed to demonstrate that there would be no choice but to negotiate, and to do so quickly.

Nixon's approach "put a gun to the head of all other countries." Many of the men who made the decision would have preferred to negotiate but Nixon and his Treasury Secretary John Connally: had concluded that holding negotiations would cause market crises. Every time there was an announcement about the negotiations, every time somebody blinked, there'd be 20 interpretations and a continual economic crisis... Nixon masterfully created a situation where suddenly countries understood that they needed coordinated policies to deal with finance, trade, energy, and food.

It's undeniable that China has growing power to influence events. But realistically, a shock strong enough to shake the world into a new system can only come from the U.S. The dollar and the main American financial institutions remain so powerful that for anything to happen, the U.S. would have to make the first move. Could a gold standard return? How? John Butler, author of The Gold Revolution, Revisited has long suggested that a return to gold is both possible and ultimately necessary, as a capstone to the financial system. But how to get there? He admits that, as in the answer to the old joke, "If I were you, I wouldn't start from here." It isn't politically possible without first undergoing a return to severe inflation. He suggests that ultimately the international financial imbalances that have built up since the end of Bretton Woods can only be reconciled as a result of unilateral action: "Let's say the U.S. government is really enlightened and decides that the monetary system isn't fit for purpose, and that they need to re-peg to gold. They should announce: 'This isn't working. It's not in our interest or your interest. The best way is to move back to gold. Two years from today, we'll take the average dollar gold price in the market over the past 30 days or 90 days, and we will fix the peg right there. We want you in the international markets to figure out how to move he existing exchange rates and security prices to where they would need to be to clear the market and reduce the imbalances, such that in two years' time we start out with an orderly financial system."

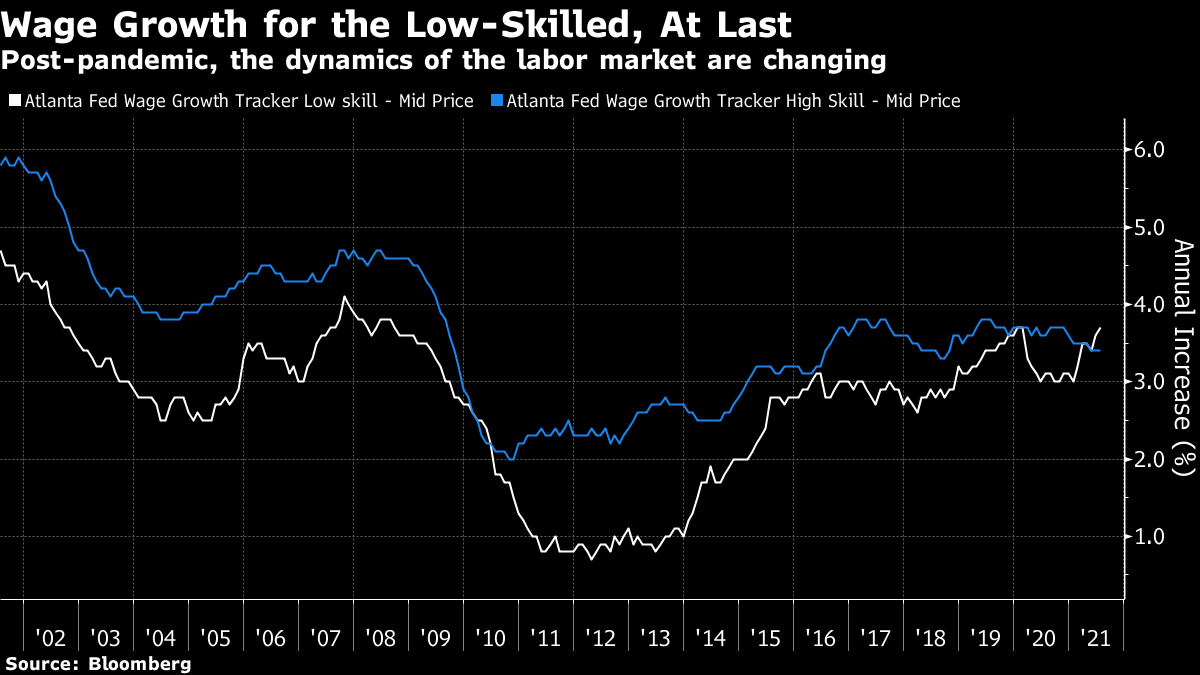

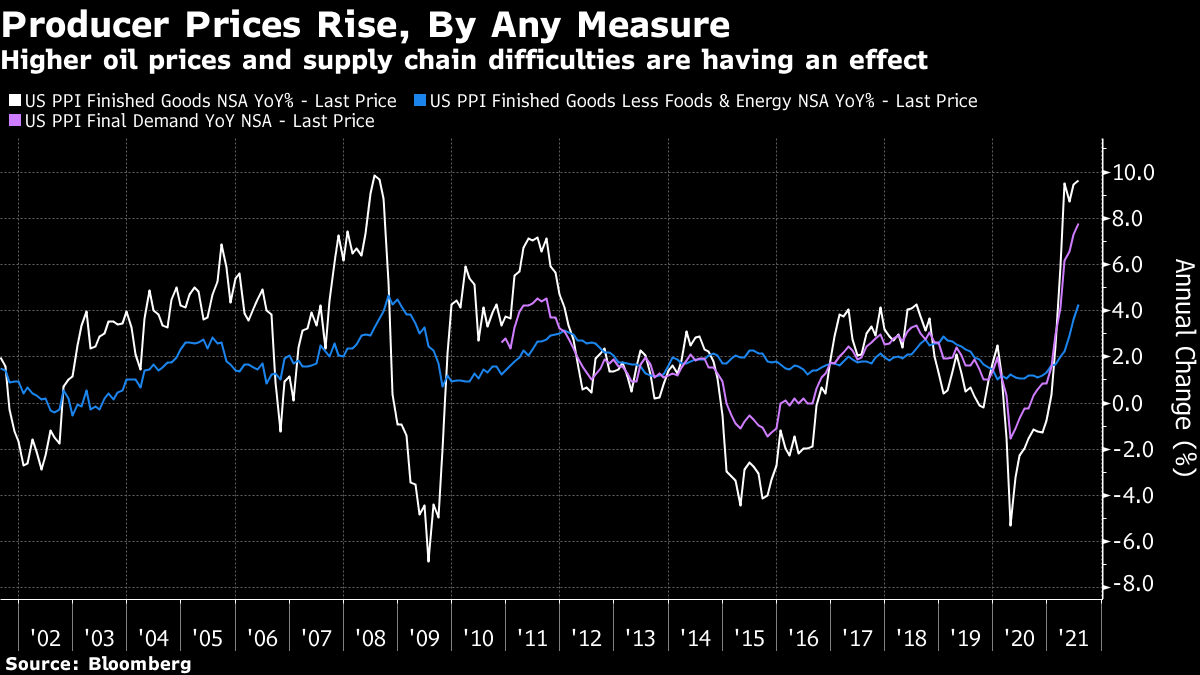

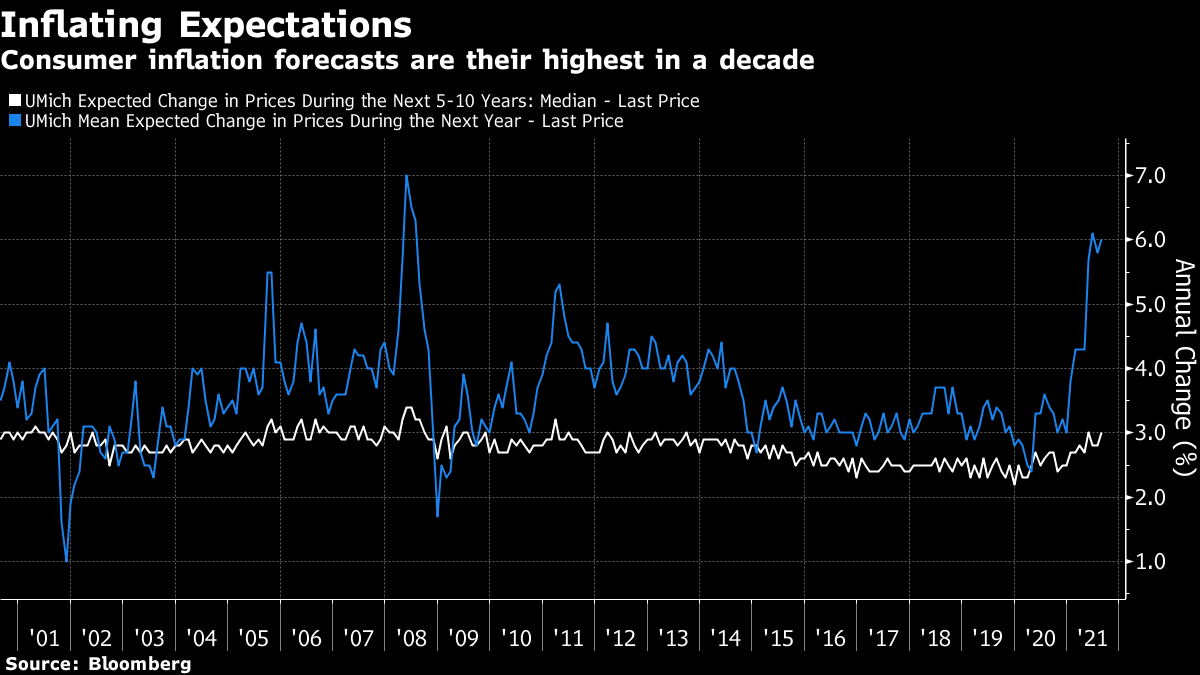

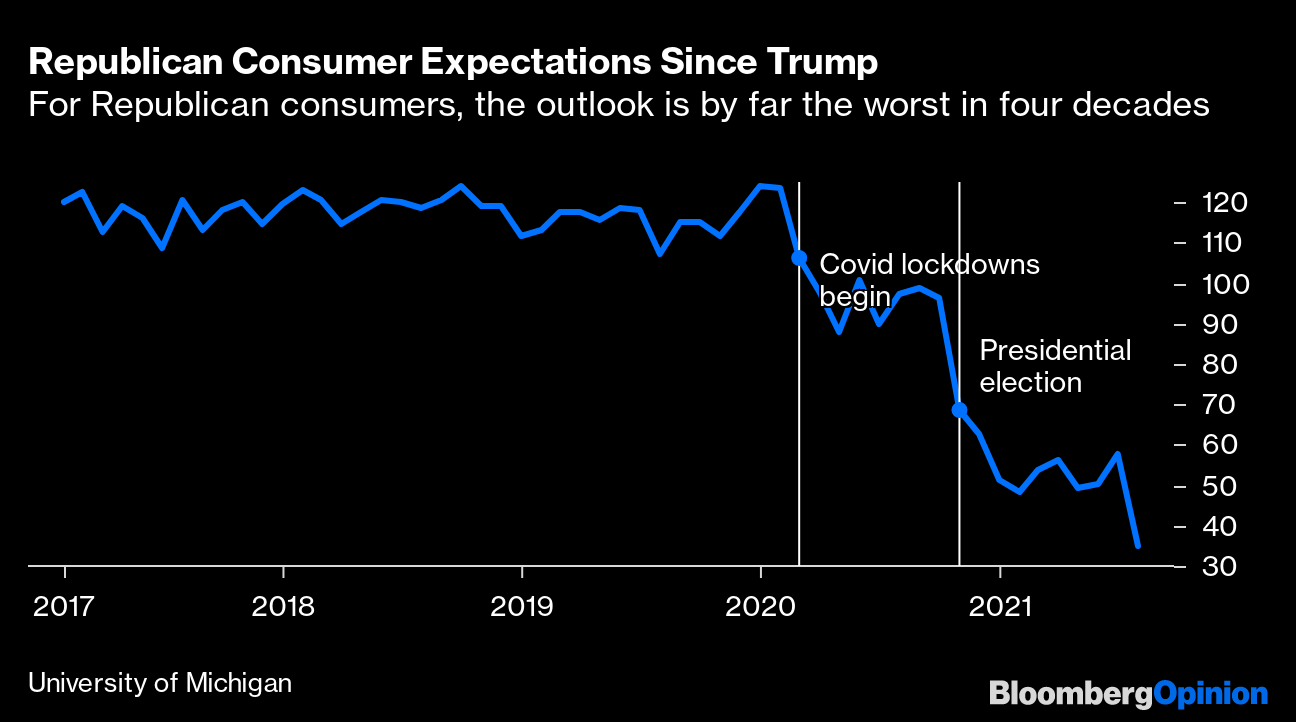

The idea is that this would give everyone the chance to use the market to find out how to reconcile the imbalances that have built up over the last 50 years. Butler points out that this would involve asking much the same questions of developed markets that analysts and investors have long asked of emerging markets. He also concedes that it would be disruptive, and inflationary. A large part of the answer to excessive leverage would come through inflation, which would happen through a massive increase in the gold price, and hence depreciation of the dollar. He modestly suggests, though, that disruption would be less if done in the way that he proposes. The chances of such a thing happening are between slim and non-existent, at least without a crisis first. Comments are welcome, as there will be more on this theme as the week goes on. But one other point is clear — the necessary precondition for any real regime change would be a inflationary crisis. What are the risks that we have one of those? So, let's get back to the inflation debate. We update the running indicators tomorrow, but there has been a lot of news in the last week, albeit without any great new clarity. As might be expected, economists' expectations have at last caught up with the state of the recovery from the pandemic. For the first time since June last year, Citigroup Inc.'s widely followed macro surprise index is below 100; on balance, people have been disappointed by the incoming data in the last week:  There has been new wage data, critical to any possibility of a resumed upward inflation spiral. As the Atlanta Fed's Wage Tracker data show, something is going on in the structure of the labor market. Wage growth for the low-skilled is as high as it has been in a decade (great news, unless you are particularly worried by inflation), and exceeds that of the high-skilled by the most on record, having surpassed it for the first time in more than a decade:  The latest producer price figures show continuing inflation pressure. Using the old methodology, PPI ticked up to the highest level since 2008, as did core CPI. "Final demand" PPI, the official measure these days, is lower than the old number, but is currently increasing much more rapidly. News of pandemic-enforced container port closures in Asia suggest that pressure on producer prices isn't going away:  Consumer expectations, another critical ingredient of any secular rise in inflation, ticked up both for the next 12 months and for the next 5-10 years in the University of Michigan's survey. Expectations for the next year are their highest since 2008; longer-term expectations, at 3%, remain within the range for the last decade:  The consumer sentiment headline number in the Michigan report dived back to its worst levels of the pandemic, alarming markets Friday. Looking into the detail, perhaps the most frightening point is the degree of partisan difference. As is widely noted these days, adherents of the two main parties seem to be inhabiting different realities. Expectations of people who described themselves as Republicans have fallen off a cliff:  The latest number is 10 points below the 45.5 nadir for Democrats' consumer expectations in May of last year, the month when President Trump suggested injecting disinfectant as a cure for Covid. It is below the previous low for Republicans' expectations, in March 2009, when the market collapsed. It is also far below June 1980, the first month in which the University of Michigan reported this answer in partisan terms. Under President Jimmy Carter, who was still looking competitive in the polls, and against the backdrop of American hostages in Iran, a Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, and stagflation at home, Democrats' expectations fell to 54.2, while Republicans' dropped to 51.1. Extreme polarization is a recent phenomenon. There are obvious and alarming issues for social cohesion. Rather more than a third of Americans think the economic outlook is the bleakest in living memory, and this was before the shocking news of the Taliban's victory. Such pessimism can be self-fulfilling. This is a request for a survival tip. Thanks to a change in British policy to recognize vaccinations that have been received in the U.S., I am heading to the U.K. at the end of the week. It's been my longest time without taking a plane flight since I left high school (good news for the environment). So, does anyone out there have advice on traveling in the current environment? I've got the VeriFLY app, which I have been told is very useful for dealing with the official medical hassles, and I've invested in N95 masks to wear on board. I really don't want to get Covid just before I see my aged parents again for the first time in more than a year. I'll share good advice. Have a good week, everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment