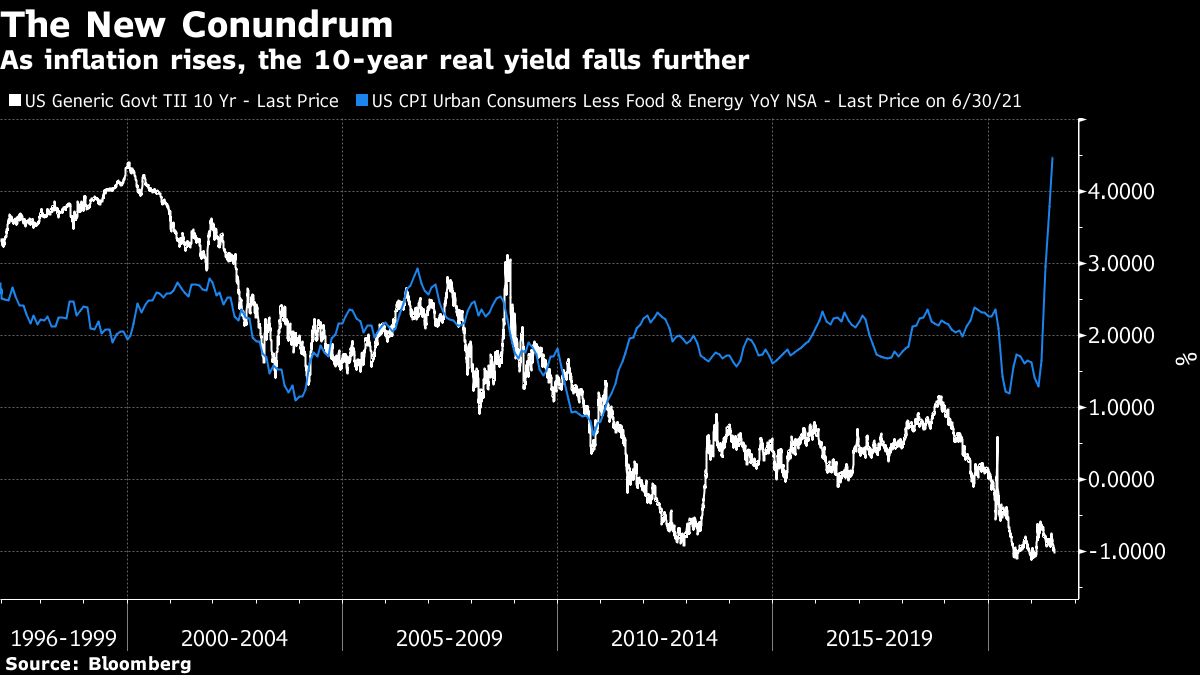

Return of the ConundrumThe bond market has another conundrum. Almost 20 years ago, Alan Greenspan admitted that it was a "conundrum" that longer bond yields barely rose as he steadily raised short-term rates in his latter years at the Federal Reserve. Now, inflation may or may not prove to be transitory, but it is the highest in decades. Month after month, the official numbers have turned out higher than expected. With higher inflation, investors should in theory demand a higher yield from bonds to compensate for the erosion of buying power. And any suggestion that interest rates are going to go up should, as Greenspan implied, lead to higher long-term yields. Yet they are falling. The conundrum is most pressing if we look at the yields on Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, whose ultimate payout at redemption is tied to inflation. People are prepared to buy them for a yield of -1%. The varying paths of core inflation and the 10-year TIPS yield look truly bizarre:  In the short term, it's easy to see why yields fell Wednesday. Jerome Powell, chairman of the Fed, took questions from Congress the day after that shocking but also very strange inflation number, and doused speculation that he was about to start tightening policy. This testimony has been a great opportunity in the past for Powell's predecessors to trail a forthcoming change in policy. But there was no hint that a reduction in the Fed's purchases of securities to boost the market was imminent. That won't happen until substantial further progress has been made toward reaching the central bank's employment goal. He said: While reaching the standard of "substantial further progress" is still a ways off, participants expect that progress will continue. We will continue these discussions in coming meetings. As we have said, we will provide advance notice before announcing any decision to make changes to our purchases.

This was an opportunity to provide that advance notice, and he didn't take it. So that was the cue for rates to go down a little. That said, the market is slowly bracing for rates to rise in the foreseeable future. If we look at the three-year bond yield, which should increase if markets expect a hike in the Fed's overnight rate within the next three years, it is clear that expectations of some tightening have been brought forward:  So why are longer bond yields falling? The issue dominates discussion in my inbox, and probably in most other places where markets are talked about. Perhaps the best summary I have seen of the "conventional wisdom" list of justifications for falling yields is as follows, from Robert Ostrowski of Federated Hermes: - We've already reached peak/transitory inflation and the hullaballoo over rising prices is overdone (arguably Chair Powell's base case).

- We're at peak growth (although an economy moderating off near double-digit growth is still unusually strong).

- Having benefited from record stock prices, pensions are rebalancing into bonds.

- Relative to low and negative rates in much of the world, U.S. Treasuries remain attractive to non-U.S. investors.

- And investors positioned for rates to rise, not fall—the vast consensus trade—are being forced to unwind positions.

As Ostrowski says, "virtually all the above would suggest another leg up in yields awaits," and Federated Hermes believes this will prove to be the case. This is a list of fundamentally transitory, but good reasons for people to buy bonds at present. They aren't reasons for bond yields to stay where they are for months or years into the future. The list is also handy for reminding us that there are reasons beyond expected inflation or the expected behavior of the Fed for people to buy bonds, particularly if they are regulatorily required to do so at some point, or if they inhabit one of the many jurisdictions where yields are even lower than they are in the U.S. That said, falling longer yields, combined with rising short-term yields, more or less directly imply a hawkish mistake by the Fed. Rising short-term yields show growing expectation of higher rates in the short term, while falling longer-term yields suggest the market thinks that the tightening will choke off longer-term growth. Leaving aside the weirdness of accusing a central bank of doing anything too hawkishly when it has deliberately brought rates to zero and presided over the fastest peacetime money supply growth in history, it is fair to say that the Fed has a tendency to try to tighten earlier than the market thinks it should, and to get in a mess because of it. It is arguably the whole point of the new policy framework unveiled in Jackson Hole in August last year that the Fed is saying it won't make the same mistake again; it will be happy for inflation to be above target for a while, and it will wait for solid data showing that it is picking up, rather than responding merely to expectations — more or less a promise to be behind the curve. Nevertheless, the bond market seems to be betting that the Fed will chicken out and tighten too soon again. Thomas Tzitzouris of Strategas Research Partners puts this argument cynically but fairly, in a comment issued before Powell's testimony: Tighten until something breaks. Like a surgeon that always wants to cut, the Fed, over the last 40+ years, has consistently chosen to tighten more than the bond market said was warranted. So betting odds would suggest that once inflation enters an uncomfortable zone, the Fed is going to respond by raising short rates more than they should, and thus forcing long rates lower, all the while scratching their head and uttering gibberish about why the move in long rates doesn't make sense. That may seem a tad bit cynical for a Wednesday morning in July, but if you're of this mindset, then you would very likely have covered some of your shorts in 10s yesterday morning after the CPI, and moved them into the 2 year part of the curve. That appears to be exactly what happened in the early going after the CPI release, and we have to think that this was the bond market's way of saying "policy mistake is coming". We're not convinced that the Powell Fed will make this mistake, at least not before 2023, but the bond market seems ever more certain that the mistake is coming, and perhaps as soon as next June.

The other big school of thought is that the weight of people buying bonds believe in "secular stagnation." If we're not going to achieve much growth, despite all the money that's been thrown at the problem, then we'll stay in a deflationary environment, and lower bond yields would be appropriate. There are many who still think the notion of rising inflation in the longer term is ridiculous, and that the rises we are suffering at present will choke off inflation in the future. For a recent example, there was a massive oil price spike in the summer of 2008 that briefly alarmed investors and even prompted the European Central Bank to raise its target rates, on the eve of a credit crisis. That oil spike soon reversed, and ushered in a brief but brutal period of deflation. It was the inflation that cured itself, without intervention from central banks. None of this holds, however, if price rises are part of a cyclical upswing in the economy. Then they will become self-reinforcing, as demand increases. For a few months earlier this year, everyone seemed to have convinced themselves that this would happen (without that much evidence). Now they seem to have convinced themselves of the opposite (again without much new evidence). I think this point from Andrew Brigden, of Fathom Financial Consulting in London, is well made: It is becoming increasingly apparent that the pick-up taking place in inflation, particularly in the US, is cyclical. It is not just a consequence of base effects. Traditionally, any cyclical pick-up in inflation has required a monetary policy response. But that is not the intention of policymakers at present. The FOMC continues to believe that the pick-up will be transitory. We have our doubts. Inflation overshoots driven by a spike in the oil price, by a change in tax rates, or by a depreciation of the currency, tend ultimately to subtract from household real incomes. In that sense, they can be self-limiting, and deflationary in the long run, and it is often appropriate for policymakers to look through them. But that is not what we are seeing here. Only in the unlikely event that higher product prices do not feed through at all to higher wages, which would require a very strong degree of faith in policymakers' ability to rapidly bring inflation back to target, would a cyclical pick-up in inflation be self limiting.

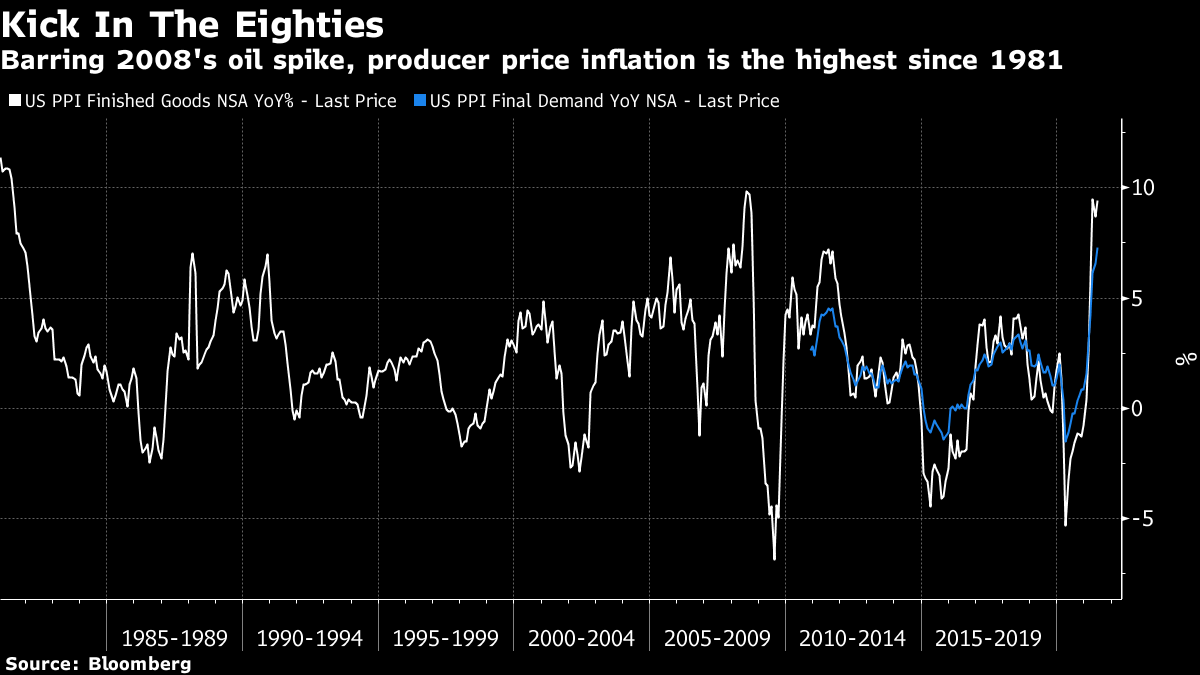

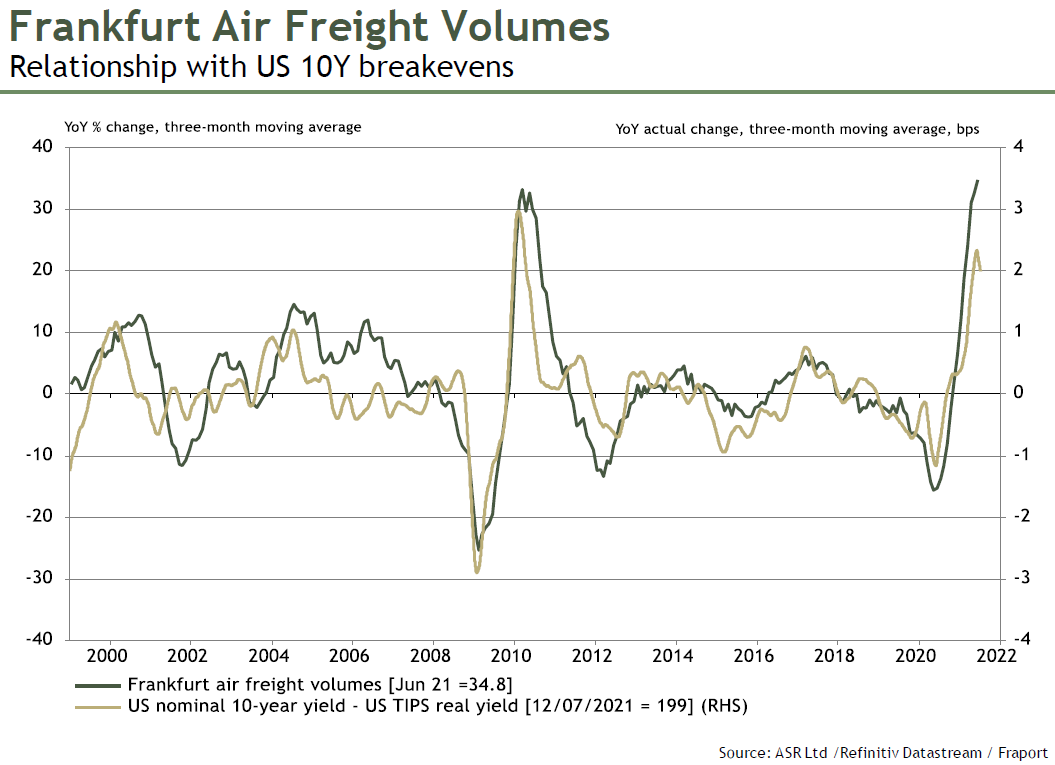

That is an argument, in other words, for bracing for a dovish mistake — which would presage a significant rise in inflation. I won't go over all the arguments for whether inflation is truly transitory and only a pandemic phenomenon, as I tried to yesterday. But Wednesday's latest data release added to the narrative that the Fed would be making a mistake if it stayed its hand. This is producer price inflation, shown both on the current basis that has been calculated for the last 10 years, and on the basis used before that, which is still published. They disagree on the level of inflation in the prices that producers pay; they are in agreement as to the direction.  Yes, the last time it spiked like this, it was followed by a crash to the lowest level in history. But a) the oil price then was double what it is now, and b) an epochal credit crisis also had something to do with this. It would be wise at least to take this spike seriously. For one more piece of evidence that there is some degree of reopening oomph in the economy, I offer Frankfurt air freight numbers, as dissected for me by David Bowers of Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. in London, to whom thanks. Frankfurt is a hub for cargo transport in the European Union, and a good barometer for global trade. Over time, it also proves to have been a great gauge for U.S. earnings, U.S. margins (they rise when trade volumes in Frankfurt are rising) and, crucially, U.S. inflation expectations. There is a sudden departure from this of late:  If people are betting on secular stagnation, they should probably await more evidence before doing so. So, what is the answer to the conundrum? If I knew, I would probably be much wealthier. But my best guess is that the technical reasons cited by Ostrowski of Federated Hermes largely cover it. For this move in yields to prove more than transitory, the Fed will need to make a hawkish mistake. Survival TipsI hope French readers have had a happy Bastille Day. Free word association offers Pompeii, a lovely song by a band who call themselves Bastille, and Bastille Day, a gloriously overblown song by the Canadian prog-rockers Rush. But I know of no more glorious evocation of the French Revolution than Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique. In the unlikely event that you have an hour to spare, try closing your eyes and surrendering yourself to Berlioz's vivid imagination. Vive La France. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment