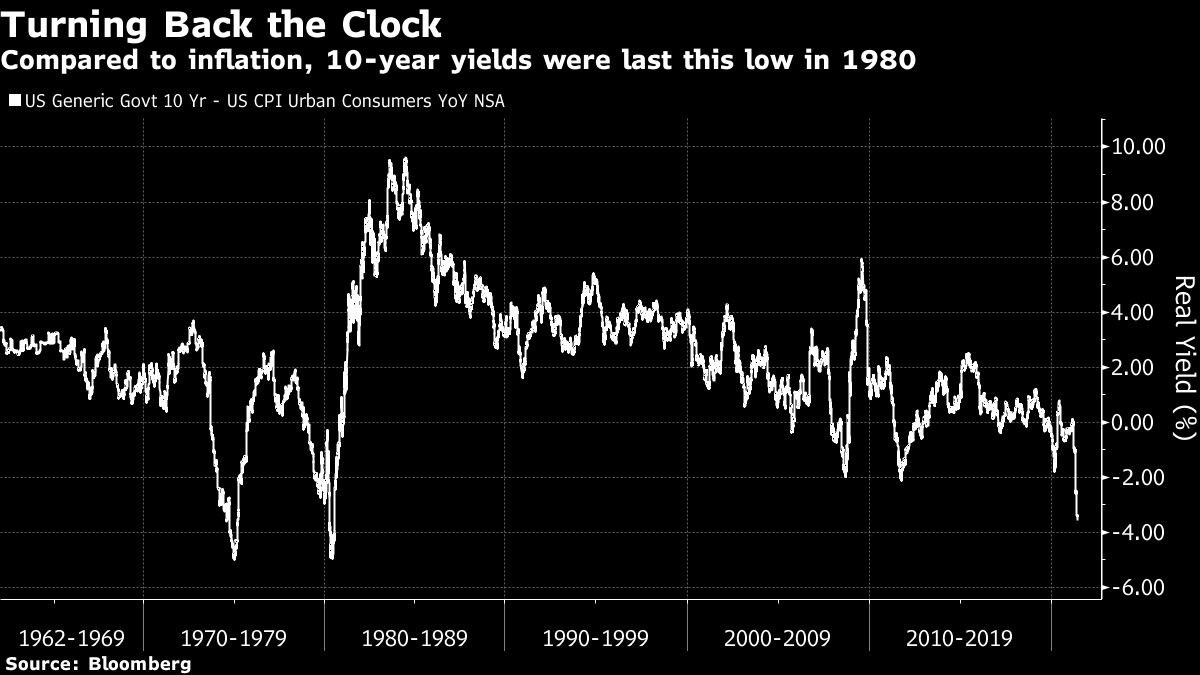

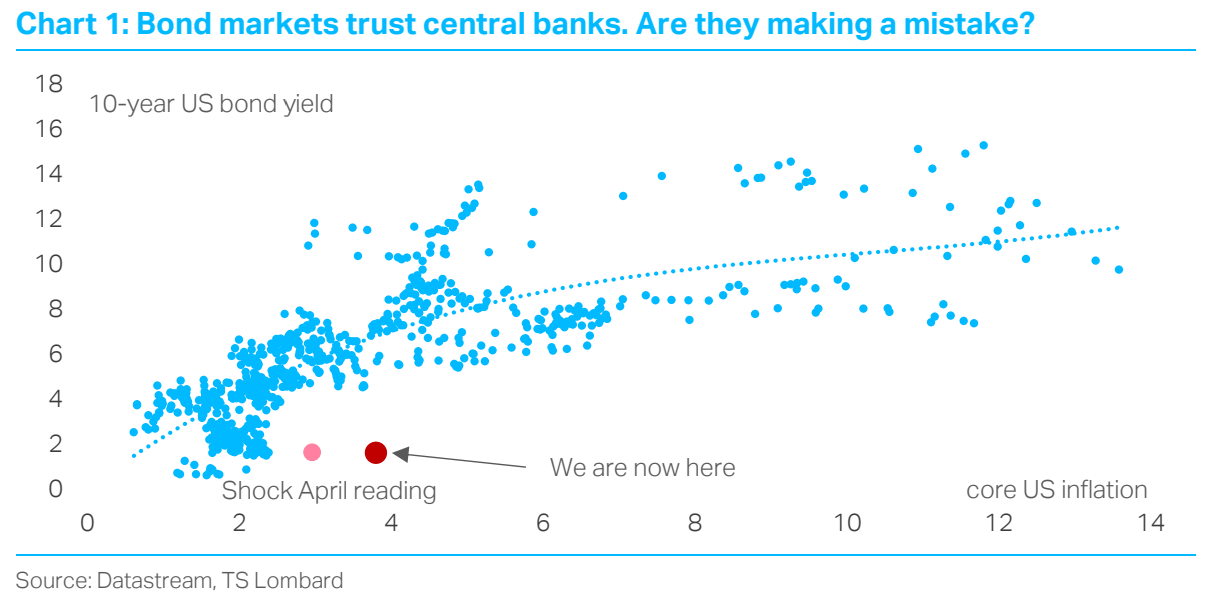

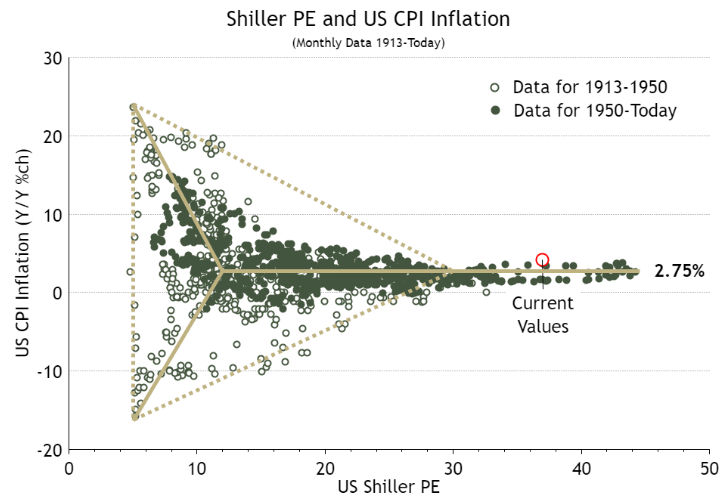

A Transitory DayThe bets have been placed. At this point, there is lots of money on the notion that U.S. inflation really is only transitory, that Jerome Powell and his colleagues at the Federal Reserve really mean it when they say that inflation is transitory, and that they care more about spurring a rise in employment. These propositions aren't so far-fetched. But the confidence with which they are now being backed on the market does look most far-fetched, at least to me. This was a day when core inflation in the U.S. was revealed to be running at its fastest in 29 years, and faster than expectations — and yet it also saw the S&P 500 rally to a new all-time high. I will try to illustrate how extreme this is. To be clear, we all knew that inflation would rise during these months, thanks to the comparison with the deflationary conditions amid the worst of the pandemic 12 months ago. Everyone had an inflation scare marked in their diaries for about now. Few can have reckoned on the scare dissipating in markets just as the inflation numbers came through on cue and higher than expected. Headline inflation has reached 5% for only the second time in 30 years. It had only been higher during the oil spike of 2008:  This may well be transitory, but it's certainly rather alarming. The market reaction is arguably even more unnerving, and certainly more extreme. If we define real long-term interest rates as the 10-year Treasury yield minus the headline inflation rate (which is the way many people would), then real yields have tanked to minus 3.7%. In the last 70 years, they have only been lower than this in 10 months, all during the worst inflationary years of 1974 and 1980. In other words, real yields are by far their lowest since the Fed under Paul Volcker convinced the market that it could control inflation in the early 1980s. In a way, we have already left the Volcker era of monetary policy:  My thanks to Jim Reid of Deutsche Bank AG for pointing out this version of the real yield. If we define it as the yield on 10-year Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, we get only a slightly less extreme picture. The low on this basis was a few months ago; but yields remain at negative levels that until recently were unimaginable:  These are critical measures suggesting that financial conditions are exceptionally easy. There is very little insurance here against the risk that inflation proves more durable than many now expect. The Goldman Sachs U.S. Financial Conditions index, a broader measure that includes factors such as valuations on stocks and the availability of liquidity and banking finance, has just hit its lowest level since it was started nearly 40 years ago (Bloomberg has a similar index that is slightly above its low):  This is an extremely strange set of conditions to combine with the worst inflation print in decades, even if that inflation is transitory. Both bond and equity investors have pushed out the boat a long way. This chart from Dario Perkins of TS Lombard in London illustrates the extremity of the bond market nicely. It maps 10-year yields on the vertical scale, against core inflation. Usually, and unsurprisingly, higher inflation tends to mean higher bond yields. The current yield looks like a historic outlier. Arguably, bond yields have never been this tolerant of high inflation. As Perkins suggests in his title, bond markets are putting an awful lot of trust in central banks not to let inflation get going (which would damage longer-term bond returns):  As for the stock market, I published last week this similar exercise produced by Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research Ltd. in London, which puts inflation on the vertical axis and the Shiller price-earnings ratio on the horizontal axis. This produced a relationship you could call the "Inflation Dart" or perhaps preferably "Inflation Concorde." The relationship between inflation and share valuations isn't as tight as with bonds, of course, but at present the Shiller P/E is at the historically extreme level of 37 (slightly to the right of the red ring on the chart). In the past, such valuations have only ever been achieved when inflation is positive and very low. With inflation at 5%, the latest reading is a massive outlier. There is no precedent for the stock market being prepared to look through inflation this high and leave multiples at such an elevated level (or indeed set a new all-time record):  So markets are staking a lot on the notion that this inflation number itself will prove to be a freakish outlier, soon to be corrected. What is the case that they are right? Sic Transit Gloria?There is a good case that these inflation numbers will reduce before long. I would summarize the three main supports as follows: - Much of it is extreme inflation in reopening sectors

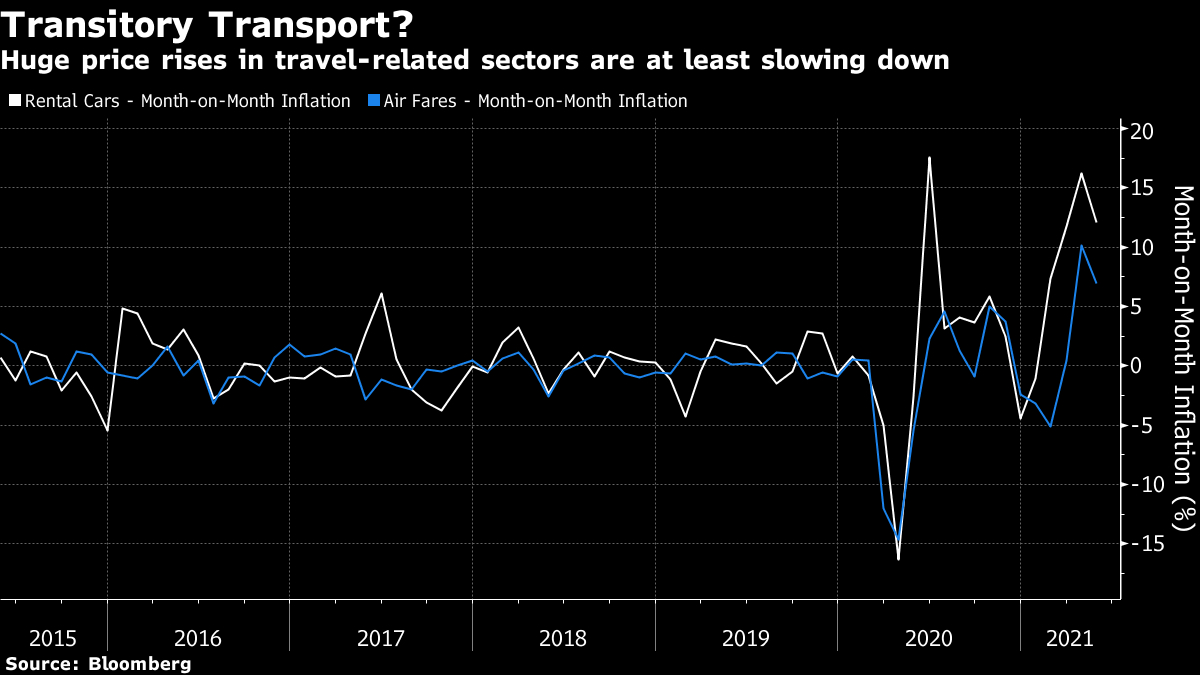

This has been much discussed, but it is true. Reopening sectors affected by the return of tourism have seen freakishly high inflation which plainly cannot continue much longer. Indeed air fares and car rentals both saw slightly smaller rises in May than in April — although in both cases the rise in prices is eye-watering. Used cars on their own account for about a third of the increase in core inflation. So yes, there are plainly elements of this inflationary episode that owe everything to the pandemic, and that need not require the central bank to take any action:  - Commodity prices have already begun to turn over

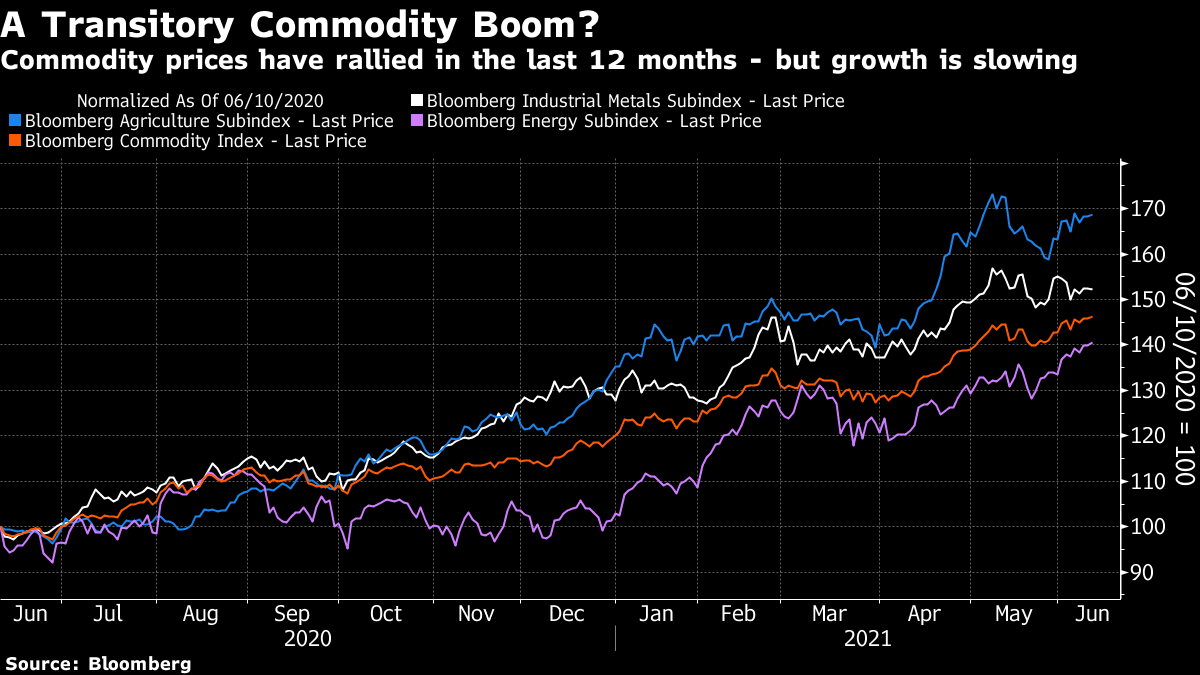

The rally in commodity prices has driven much of the belief that inflation will take off. This chart shows Bloomberg's indexes for industrial metals, agricultural commodities, and energy over the last three years. The recent fall in metals prices has received much attention, and the apparent desire of Chinese authorities to clamp down on high producer price inflation increases the downward pressure. Agricultural prices are also off their top. But energy prices are still rising, as is the overall Bloomberg index — and it isn't yet clear that metals are in a clearly defined downward trend. If commodity prices do fall much further from here, though, that would likely make sure that this inflation episode doesn't last too long:  - Wages are still well under control

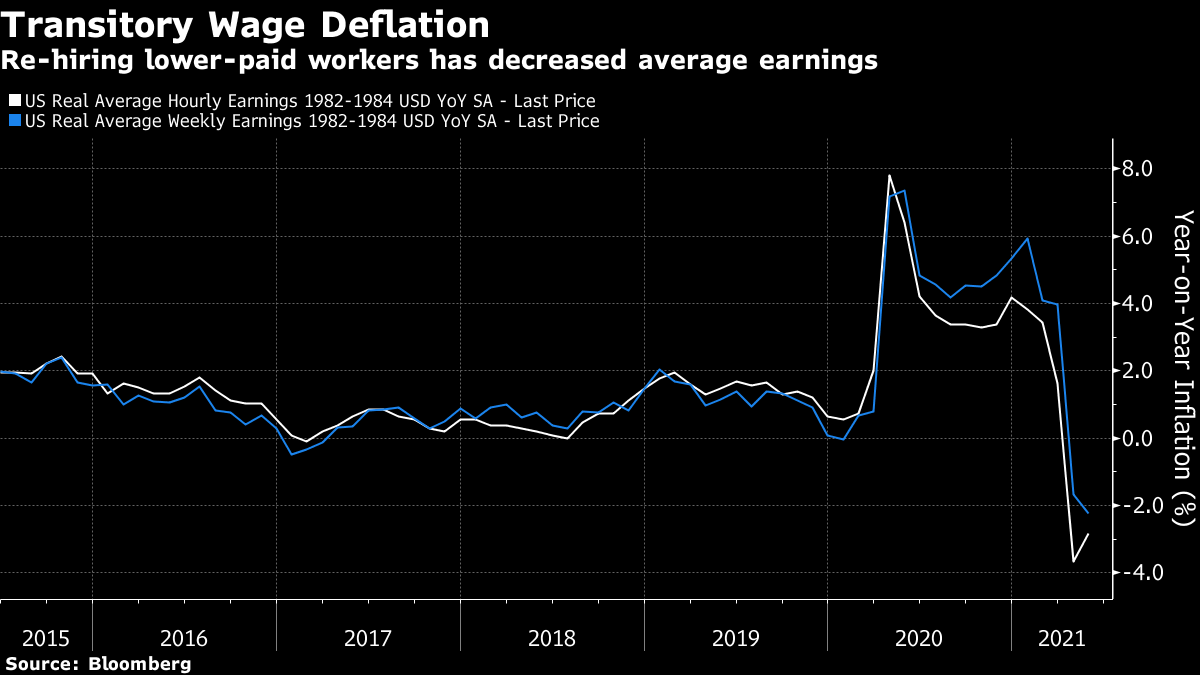

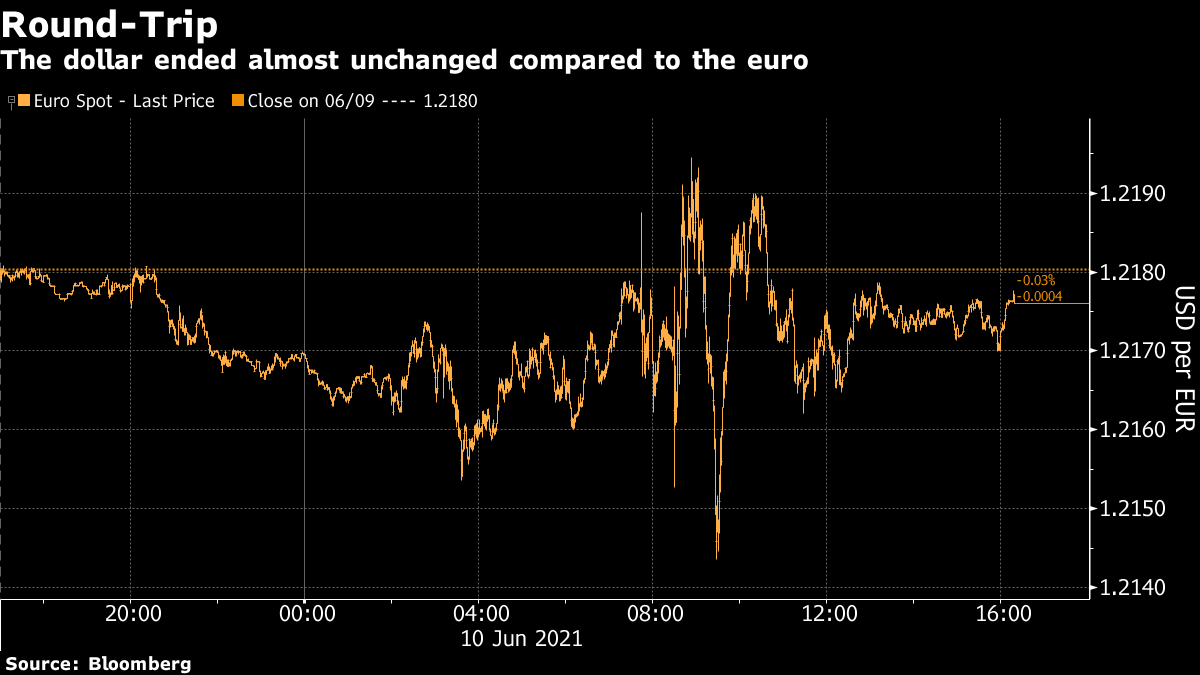

What drives inflation is expectations — both of inflation, and also wage increases. People get much happier to pay more for stuff when they are expecting better salaries in future. There has been plenty of anecdotal evidence of skill mismatches, while employers complain in surveys that they find it hard to fill vacancies. But evidence of wage pressure isn't in the official numbers, as yet. Indeed, due to a weird compositional effect, both weekly and hourly average earnings appear to be in serious deflation, having spiked remarkably higher last year. This is because the lowest-paid workers were most likely to be laid off during the pandemic, pushing up the average pay of those who remained, and are now the most likely to be rehired, pushing down the average. This is another obviously transitory effect, and the picture isn't at all clear yet. But those who believe that this is a transitory episode are right to argue that there is no evidence of wage inflation yet:  This adds up to a respectable case that this dose of inflation should soon go away. But I would question whether it is strong enough to justify quite such a confident reaction in stock and bond markets. The International AngleThe inflation print has rippled throughout the world. Declining yields in the U.S. are great news for emerging markets, still damaged by political uncertainty and the ramifications of the pandemic. Emerging market currencies received a pummeling last year. Now, the J.P. Morgan Emerging Market Currency Index is its strongest since last February, before a pandemic had even been proclaimed. The "taper tantrum" of 2013 put acute pressure on a number of emerging currencies, and the sharp rise in U.S. yields at the beginning of this year was possibly the worst tantrum since then; the reduction in U.S. yields in the last few months has substantially reduced the risk of another old-fashioned emerging markets crisis:  And then there is the euro. The other big monetary event of the day was the meeting of the European Central Bank, which ended with Christine Lagarde, its president, promising a "steady hand" and committing to "significantly higher" bond purchases over the next few months. There had been speculation that the ECB, traditionally more conservative about inflation risks than other major central banks, would try to bring down its stimulus a little; it didn't. The combination of the highest inflation number in decades in the U.S. and a surprisingly dovish ECB might have been expected to deliver a sharply higher dollar against the euro, on the back of higher yields. Instead, remarkably, the euro ended the day almost exactly where it started albeit with a few leaps of excitement along the way:  If American inflation does stay under control then one of the greater risks on the horizon, of an increasingly unbalanced global economy, reduces. A weaker dollar, more likely if U.S. yields do not rise to support it, makes life easier for a lot of people (although it also tends to pump up U.S. inflation by making imports more expensive). The market position may be right. But it has to be right both that the Fed stays as easy as it as at present, and that inflation remains under control. We've been through the risks of longer-term inflation often enough in recent weeks. Suffice it to say that both bond and stock markets look very confident, probably too confident, that they are right. Survival TipsReasons to be cheerful this weekend? I can think of two. First, European Championship soccer is about to start. International football sometimes feels like an unwelcome distraction to the mega-clubs these days, but there's still nothing like the big international tournaments. With a little luck, this one might turn out to be a coming-out party for the continent after the pandemic. And it might also produce some fun music, like South Africa in 2010 (Waka Waka by Shakira), Italia 1990 (Nessun Dorma, as sung by Pavarotti), or Three Lions of Euro 96 when, as this year, the final was in London. We can only hope. This weekend is also the premiere of Lin-Manuel Miranda's movie musical movie In The Heights, his paean of praise to Washington Heights, his native neighborhood in Uptown Manhattan. It's not until now been the most fashionable of Manhattan neighborhoods. These days known as Little Dominican Republic, at one point it hosted a huge community of German Jewish refugees who arrived in the 1930s. George Washington High School's most famous alumni give an idea of how the neighborhood has changed: Henry Kissinger, Alan Greenspan, Henry Kaufman and Manny Ramirez. Beyond Lin-Manuel's music, this neighborhood also gave the world Yeshiva University's Maccabeats, who tried their hand at Lin-Manuel's musical Hamilton. See In The Heights if you have the chance; it should raise anyone's spirits. And have a great weekend. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment