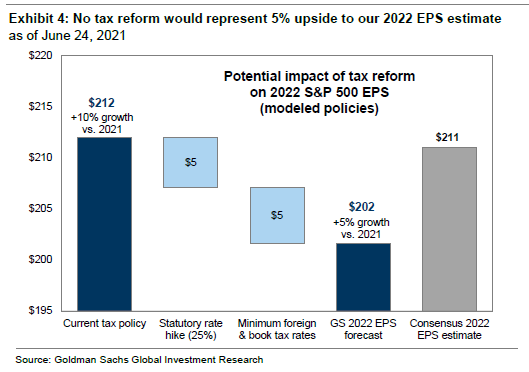

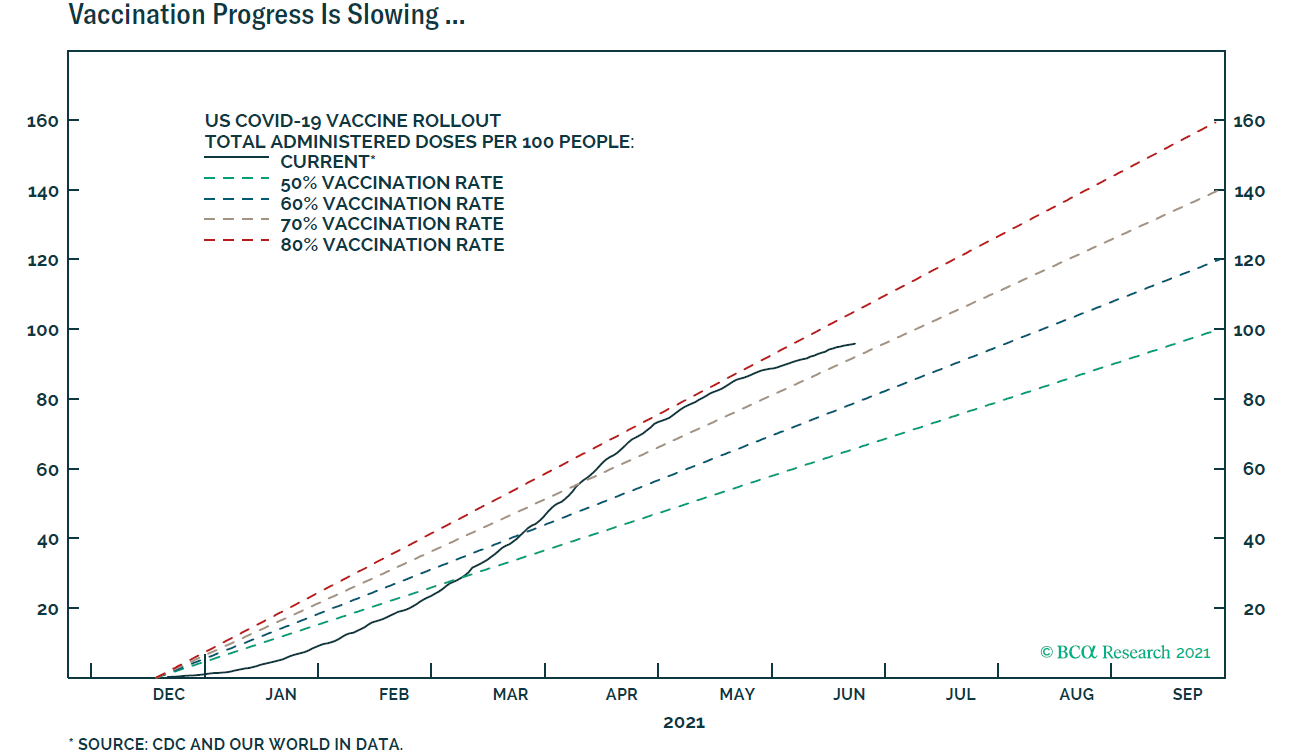

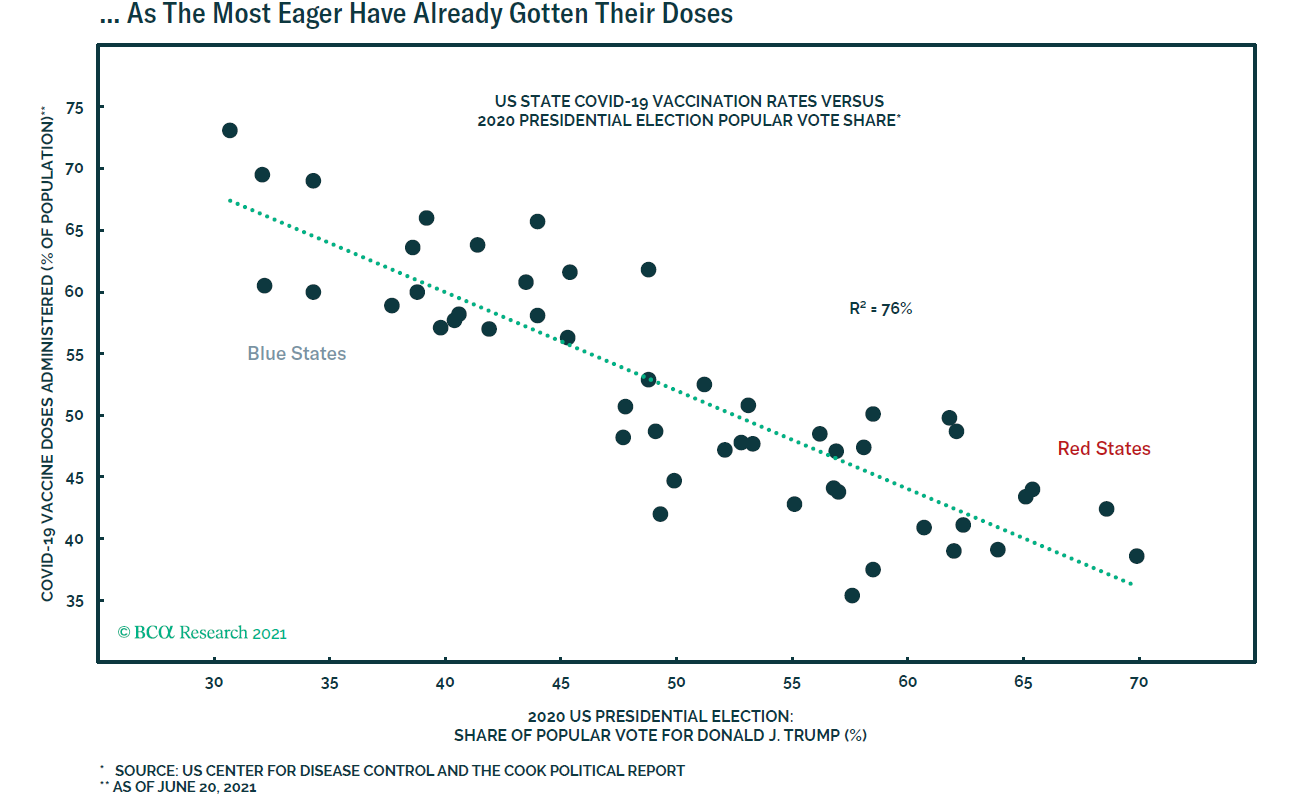

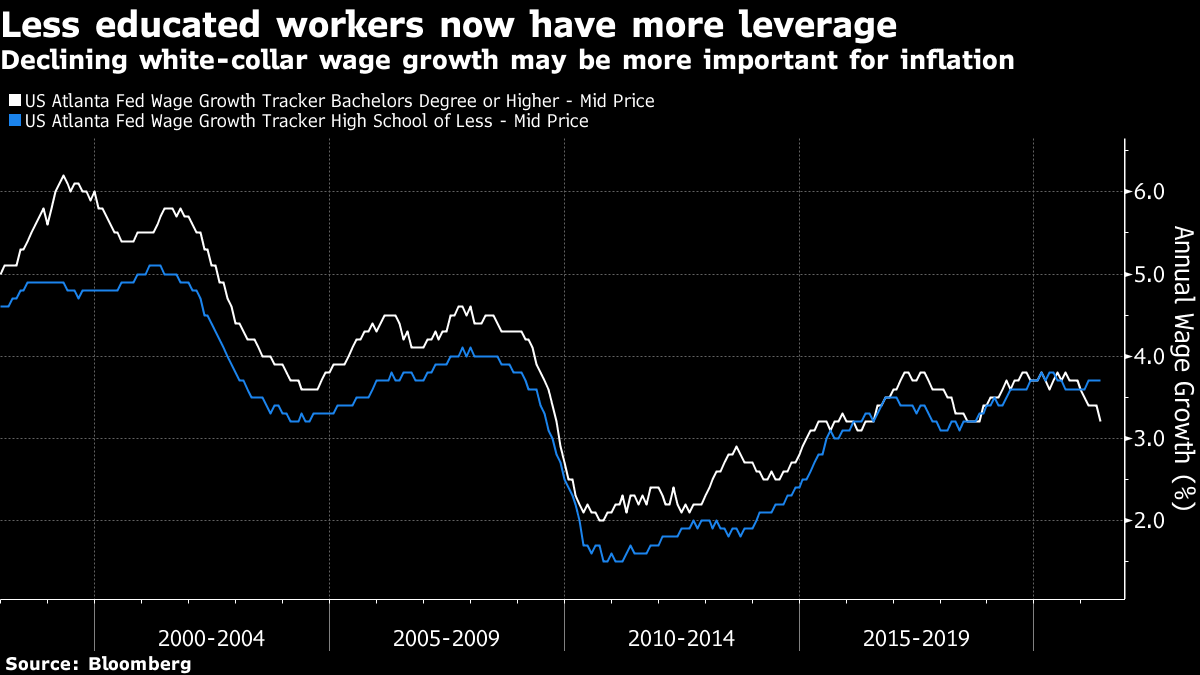

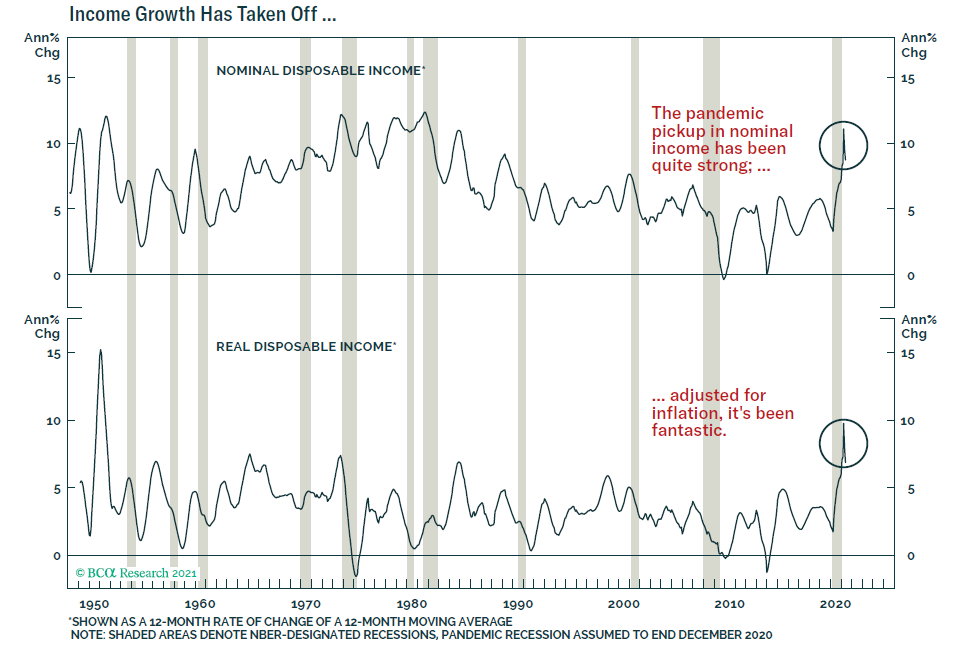

| I have a secret, proprietary database that is a great measure of market and investor sentiment. I'm not prepared to share it widely, and I haven't applied machine learning to it to create a tradable index, but I'm confident that it works. It's my email inbox. Every day, I receive several hundred messages from people hoping to sway the opinion of a market commentator. My impressionistic judgment is that this has proved a great indicator. If a large share of my inbox is trying to push me in one direction or another, or if a theme recurs, that means something. Four separate emails in the last 24 hours have asked the same question: "What is there to worry about?" That tells us that plenty of people sense complacency. They are concerned that this all appears too good to be true. Many believe markets are going well and there are few risks out there, so they are doing what they should and testing this by asking what they could be missing. The four missives I received all offered lists of things that could go wrong. They were from Barings Asset Management ("What Will Kill This Market?), Goldman Sachs Group Inc. ("What If? S&P 500 outcomes if inflation, interest rates, and tax reform deviate from our base-case forecast"), LPL Financial Holdings Inc. ("Three Things That Worry Us?"), and BCA Research Inc. ("Are We Too Optimistic?"). I'm not sure the list is exhaustive, but it gives a good idea of where investors' psychology is at present. BaringsChristopher Smart, head of the Barings Investment Institute, worries as follows: Inflation risk I, shrinking supply There's a risk that the baby-boom generation has decided to leave the labor force forever after last year's interruption, strengthening the hand of wage-earners. He'd be surprised if this were true. I agree this could be a transitory concern in the short term. The demographic shift to a relatively smaller working-age population is happening, however, and should be a long-term force pushing inflation upward. On the goods side, Smart asks if the desire for "more resilient supply chains closer to home" will drive up costs. He suggests this might happen for some medical supplies, "but we're hardly likely to see all furniture and toy manufacturing return to the U.S." While that's true, countries like China are paying workers more. In the longer term, globalization won't be as powerful a deflationary force. It's not a reason to derail the U.S. stock market this year. Inflation risk II, rising demand The biggest difference wrought by the pandemic, Smart says, is in government attitudes to spending. "Can you imagine an ambitious future U.S. candidate getting traction without promising at least a trillion dollars for some new priority?" More infrastructure spending in particular just might support a continuous rise in prices. That implies keeping an eye on the political wrangles, though it's not this year's problem. Monetary policy mistake We've all heard the argument that the Federal Reserve's policies will turn the U.S. into Zimbabwe. There's also the case that hiking too soon could crash an economy with immense amounts of debt outstanding. Smart's conclusion is that "it's hard to believe we are tightening too soon, given the strong data and generous fiscal outlook." That's fair enough, though in unprecedented circumstances, the risk of a mistake is elevated. Financial excess There's been plenty of it "from Archegos to Greensill to GameStop," but Smart say it's "still difficult to see anything on this scale cascading through a banking system that is much better capitalized and regulated than before." True; none of the incidents to date were large enough to threaten a true systemic cascade. Still, some of these examples should be viewed as symptoms of excessive risk appetite. New Covid variants Smart says: "They're worrying, of course, but the vaccines are still impressive, and extensive lockdowns seem possible only under extreme circumstances." More on this later. Geopolitical crisis You name it. He summarizes: "Rising tensions in the Middle East, missile tests in North Korea, or Something Else Really Bad Happening Somewhere!" Last year started with a frisson of fear over the American decision to assassinate a senior Iranian official in Baghdad. It was soon forgotten, though. There's always a risk that a geopolitical crisis will blow up somewhere. There's no particular reason to think that risk is any higher than usual. Cyberattack "OK, this one does keep me up a lot of nights," admits Smart. "But, as frightening as the prospect may be, it's still too theoretical for markets to price properly." That's probably right; nevertheless, such a vulnerability might be a reminder that it's unwise to price stocks for perfection, as they are at present. LPL FinancialThe concerns of Ryan Detrick, chief market strategist for the network of financial advisers, relate to technical stock market factors: Year two tends to be choppy "The good news is the second year of every single bull market since World War II has seen the S&P 500 climb higher. That is 12 for 12 for year two gains." The bad news is that "for many of the past bull markets, year-two gains were quite muted." This is LPL Financial's chart of the first two years of the last four bull markets. It's fair to expect choppiness:  Fewer stocks making new highs "Under the surface fewer stocks have been participating. Just 15% of the stocks in the index hit a new one-month high along with the benchmark on June 24, and for the first time since December 1999, a record closing high occurred with less than half of the stocks in the index above their 50-day moving averages." The S&P's latest leg-up has been driven by the mega-cap FANG internet companies, in a retreat from the "reopening trade." On the face if, that's unhealthy. A narrower market driven once more by growth stocks suggests recurring fears that growth will be scarce. Elevated Stock Valuations LPL accurately says that stock valuations have become a widespread concern, though adds that "they look quite reasonable when low interest rates are factored in." This is a long-running debate. Suffice it to say that multiples do look extreme, and that the rally of the last year, combined with the rise in bond yields, has made them far harder to justify on the grounds of low rates. More later. Goldman SachsDavid Kostin, chief U.S. equity strategist, tested three possible changes to Goldman's current forecast. The S&P is close to the investment bank's 4,300 year-end target, so by extension moves from here will depend on how these questions are resolved. "What if inflation does not prove transitory?" We've all been agonizing over this for months. Goldman's core assumption is that core CPI will fall to 2.3% next year, which would count as transitory, although it is slightly higher than the Fed's forecast of 2.1%. If this is wrong, then every extra percentage point of CPI would raise S&P 500 sales by one percentage point, while reducing net profit margins by about 10 basis points, leaving earnings per share roughly unchanged. The problem would be for earnings multiples. To protect themselves from inflation, investors would expect to pay less. Overall, the median return for the S&P 500 since 1960 has been 15% in periods of low inflation, against 9% in periods of high inflation. If the CPI keeps rising consistently from here (something few now expect), that would be seriously problematic for a stock market that's already up more than 13% for the year. "What if interest rates fall or rise more than we anticipate?" The greatest import of an inflation mistake would be on interest rates. Higher rates are bad news for share prices, all else equal, and Goldman is expecting them. Its current forecast is for a 10-year Treasury yield of 1.9% by year's end. Having reached 1.74% three months ago, the 10-year yield is now at 1.48%. So there's room for a fairly significant rise over the next six months without messing up Goldman's arithmetic. Should rates stay where they are, then all things equal Goldman's model suggests a fair value for the S&P of 4,700, a 9% gain from here. However, all things probably wouldn't be equal, and rates this low at year's end would imply a significant disappointment on economic growth, and therefore an S&P somewhat below 4,700, either because of lower earnings or because investors wanted a higher equity risk premium (or most likely a bit of both). A mistake in the other direction, with 10-year yields surging to 2.5%, would imply an S&P of 3,550 by year's end — a 17% fall from now. But that would require a lot of other forecasts to be wrong. The most bearish inflation predictions would need to come true. "What if tax reform doesn't pass?" The bad news for President Biden is that betting markets suggest he will fail to get any corporate tax increase through Congress. The good news for those hoping stocks go up is that Goldman's year-end forecast assumes he will. If there is no tax hike to weigh on the market, then the S&P can do better than its current target. Goldman is braced for $202 in earnings per share next year, on the assumption that the tax rate rises to 25% from 21%. If it stays at 21%, then earnings per share of $212 should be possible. Feeding that into the spreadsheet gives an S&P 500 of 4,500 by the end of this year — so there's room for a further gain of 5% or so if Biden fails. Here is the mathematics:  BCA ResearchDoug Peta, chief U.S. investment strategist, offered the following possibilities: The pandemic isn't over The implicit assumption is that it is (at least in the developed world). The worry is about vaccination rates, which are coming to a halt at a level that may not be enough to provide herd immunity. A large chunk of the population doesn't want to be vaccinated. Here is the U.S. progress:  The nightmare scenario is that the program stalls long enough for a more deadly variant to take hold. As seen in the U.K. (and covered in Points of Return yesterday), a new variant in the unvaccinated community has the potential to keep economic activity limited, and delay monetary tightening. So far, it isn't clear that the delta variant in the U.K. is leading to serious cases, and Peta is probably right to say that a Covid resurgence isn't likely to pull the rug out from under the U.S. economy. If the pandemic does flare again, though, the politicization of vaccinations could make things uglier:  Global softness The concern is China. Once the Communist Party's centenary is over, the fear is that it will become easier for the leadership to do whatever it feels necessary to rein in credit and avoid inflation. That would probably be good policy for China, but it's not what the rest of the world wants to see, because it would lower Chinese demand for imports:  Cost pressures BCA worries that demand for low-skilled workers "far exceeds supply." Throw in pressure over antitrust, the ESG movement, and the shrinking of the working-age population, and you have upward pressure on wage costs. Against this, however, "unskilled workers with the most leverage make the least money." Their gains don't move the needle as much as pay raises for white-collar workers would do, Peta says. This is true. Then again, poor people are much more likely to spend any extra income they receive. The Atlanta Fed's survey of wage growth shows those without a high school diploma are scoring greater increases than college graduates, in a way that hasn't been seen since records started in 1998:  The declining trend in graduates' wages could be reassuringly disinflationary, however. What if savings aren't spent? Finally, Peta points out there's a cozy assumption that American households are going to spend the $2.4 trillion in excess savings they have amassed during the pandemic, and swiftly. As this remarkable chart from BCA shows, it's almost 70 years since real disposable income has grown so fast:  That money hasn't been spent yet. There are no good precedents for consumer behavior in these circumstances. If the money continues to sit on household balance sheets, the U.S. could easily fall short of rosy economic projections. Survival TipsAfter that list of things to worry about, I will get back to worrying about England's prospects against Germany. The chance of Tuesday's game being as exciting as either of Monday's is slim; 3-3 draws don't happen often. But there have been high-scoring thrillers between England and Germany in competitive games. I offer you the highlights of the World Cup final (also at Wembley) in 1966 (England won 4-2 in part thanks to a dubious allowed goal): the World Cup quarter-final in 1970 (West Germany won 3-2 having trailed 2-0), the World Cup qualifier in Munich in 2001 (England won 5-1); and the World Cup Round of 16 fame in 2010 (Germany won 4-1, in part thanks to a wrongly disallowed England goal). Here's hoping to avoid controversy, injustice and penalty kicks. And let's all give thanks that international sport is back. It makes survival so much easier. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment