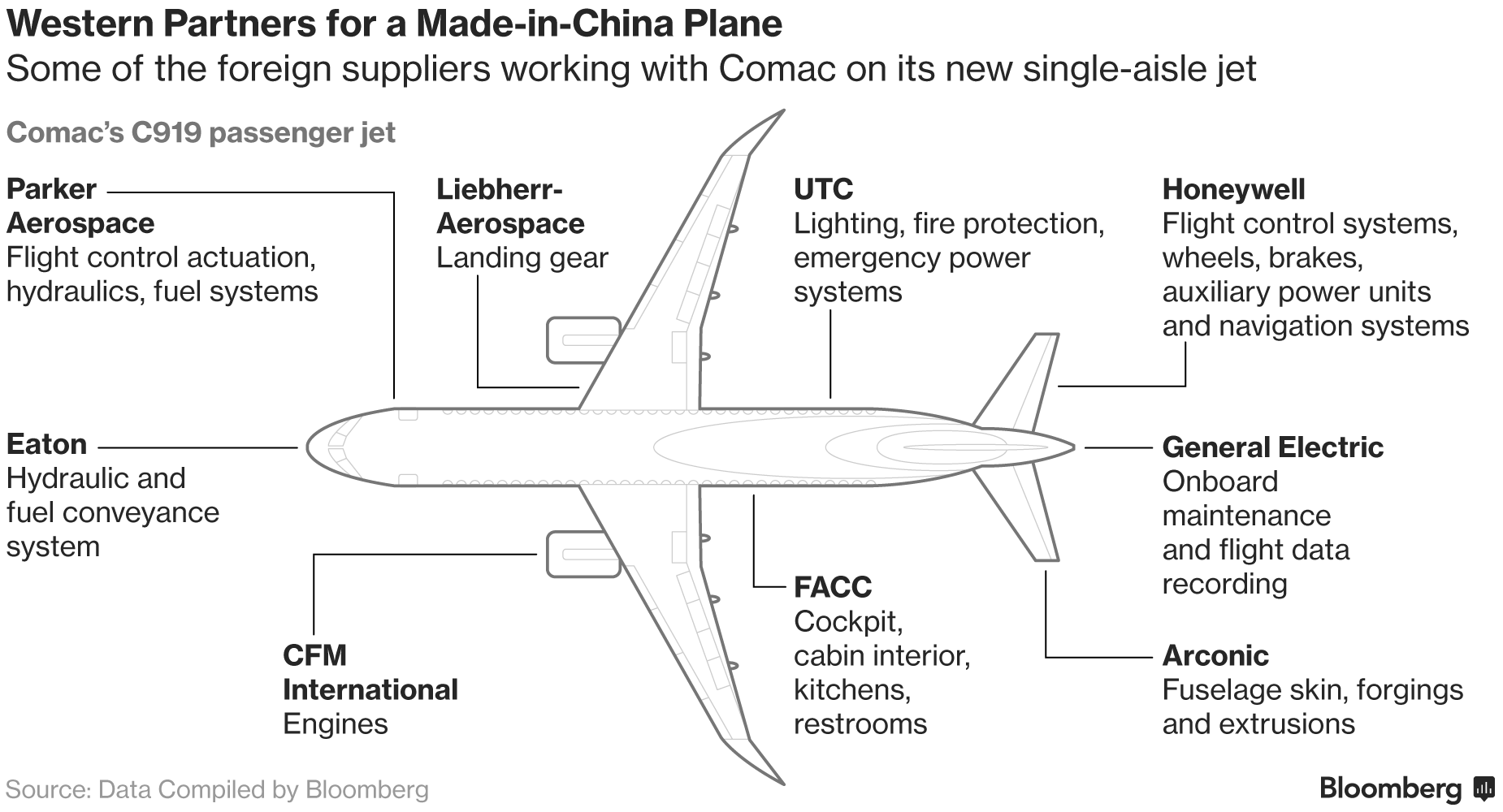

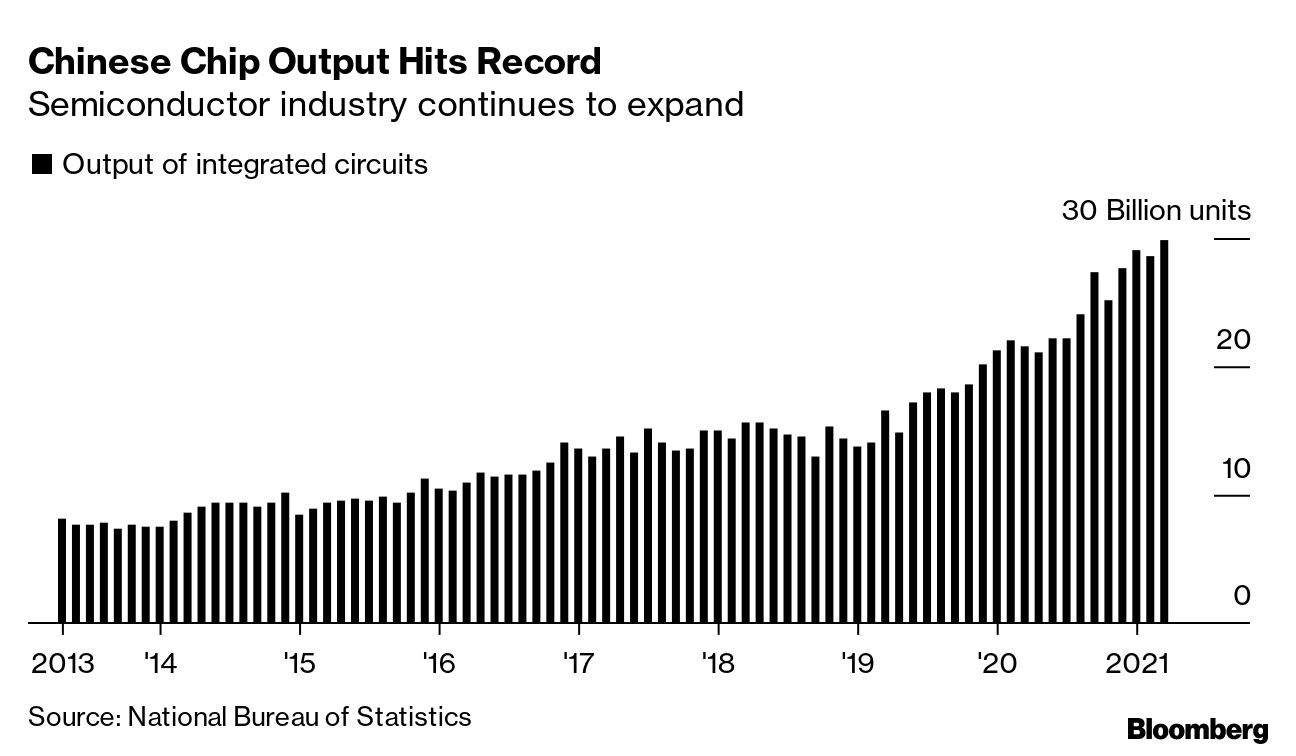

| Few things unite better than a common rival. This week, the U.S. and European Union set aside a 17-year-long dispute over subsidies for Boeing and Airbus so they could focus instead on China. Beijing's ambitions have been clear for some time. The country's state-owned national champion, Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China, began delivering its first jet — a regional plane with 90 seats — in 2015. In 2017, it tested a larger jet designed to rival Boeing's 737 and Airbus's A320 planes, with deliveries of that aircraft potentially starting by the end of this year. Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury predicted last month that Comac, as the Chinese company is known, could be a legitimate rival by the end of this decade. But before penciling in a no-holds-barred confrontation over the future of civil aviation, it is worth noting the extent of interdependences that exist in this field. If the U.S. and Europe are going to be China's rivals, they'll be rivals that need each other a lot. For one, China is home to the world's most important aviation market. Boeing predicted last year that the Chinese market will be the main driver for global aircraft demand over the next 20 years, with the country's carriers buying 8,600 planes worth $1.4 trillion during that period. Indeed, Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun warned in April that America's largest exporter can't afford to be locked out of China. And Beijing needs the U.S. and Europe just as much. Comac's C919 jet, China's best bet at competing against Boeing and Airbus in the near term, depends on components from more than a dozen foreign suppliers. Its engines are made by a joint venture between General Electric and France's Safran. Germany's Liebherr-Aerospace provides the landing gear, and Honeywell supplies the flight-control systems.  Each side has a conundrum. Washington and Brussels want Beijing to limit government support for the development of Comac's planes but would also like to see Chinese state-owned carriers buy more jets from Boeing and Airbus. China wants to take market share from those key companies but needs access to American and European suppliers to do so. There never seems to be any easy answers. Suning's Debt WoesFive years ago this month, Zhang Jindong, the billionaire founder of a sprawling business empire spanning retail to media, took control of the Inter Milan football club in Italy. That deal was cited at the time as yet another example of how Chinese tycoons were ascendant, gobbling up not just companies but also trophy properties and beloved sports teams around the world. Zhang's Suning Group looks far from ascendant today. The company's debt troubles, exacerbated by the pandemic's impact on its retail business and Zhang's decision to waive the right to a 20 billion yuan payment from Evergrande, appeared to intensify this week. It began with the company's listed unit, Suning.com, saying Tuesday that about 3 billion yuan of Zhang's stake in the company had been frozen by a Beijing court. That was followed by news late Wednesday that Zhang was looking to sell shares in the listed unit and that a 5.56% stake in that company had also been pledged as collateral for money. Both actions seemed to be part of a growing list of things Zhang has been doing to try and raise cash, including trying to sell a stake in Inter Milan.  Of course, Suning is not the only Chinese company dealing with a debt scare. Evergrande, the developer controlled by Zhang's friend and fellow billionaire Hui Ka Yan, has been roiled recently by reports that regulators are scrutinizing its finances. Huarong, the state-owned bad-loans manager whose former chairman was executed for corruption, is also trying to sell assets to raise cash. These troubles reflect one overarching reality: The regulatory environment in China has evolved tremendously in the last five years. Beijing has honed in on making sure risk in the financial system does not precipitate a crisis. That's translated into a far tighter grip on who can lend, who can borrow and how. The implications for many of China's once high-flying tycoons have been tremendous, and mainly bad. Taiwan TensionsMore than two dozen Chinese warplanes streaked through the skies around Taiwan on Tuesday, the largest incursion of its kind this year. That came after the G-7 summit in the U.K. included in its communique a call for a "peaceful resolution" of the ongoing dispute between Beijing and Taipei, the latest sign that Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen's efforts to garner international support for the self-governing island are yielding results. One way Beijing has shown its displeasure with such expressions of support has been flying jets into Taiwan's air defense identification zone. Indeed, the exercises have become an almost daily occurrence, even if the number of aircraft involved are usually not as large as what was seen this week. The incursions, meanwhile, have also raised concerns that China might be considering an even more aggressive move. That's because many of those aircraft have flown past Pratas Island, a tiny atoll that's uninhabited except for a garrison of Taiwanese marines and coast guard officers. It would be a significant and dangerous escalation if Beijing tried to take Pratas Island. Washington would be forced to decide if and how to respond, and from there it is hard to know what happens next.  China's Chip CzarThe best way to make sure something is done well is to put good people on it. So it was this week when it was revealed that Chinese Vice Premier Liu He has been asked to oversee Beijing's push to overcome U.S. sanctions in the semiconductor industry. Better known as Xi Jinping's chief trade negotiator with Washington, Liu will now be spearheading the development of third-generation chip technologies, a nascent field yet to be dominated by any one nation. That means China could leapfrog the U.S. if it gets it right. Nothing is guaranteed, of course, especially with Washington ramping up its own efforts. The U.S. House of Representatives began working this week on a version of legislation, passed last week by the Senate, aimed at bolstering government funding for developing new technologies. If the bill that results is largely the same as the Senate's, it would set aside $250 billion for that purpose, including $52 billion to expand semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S. One question that Liu's appointment as China's chip czar does raise, however, is who will be leading America's effort.  What We're ReadingAnd finally, a few other things that caught our attention: |

Post a Comment