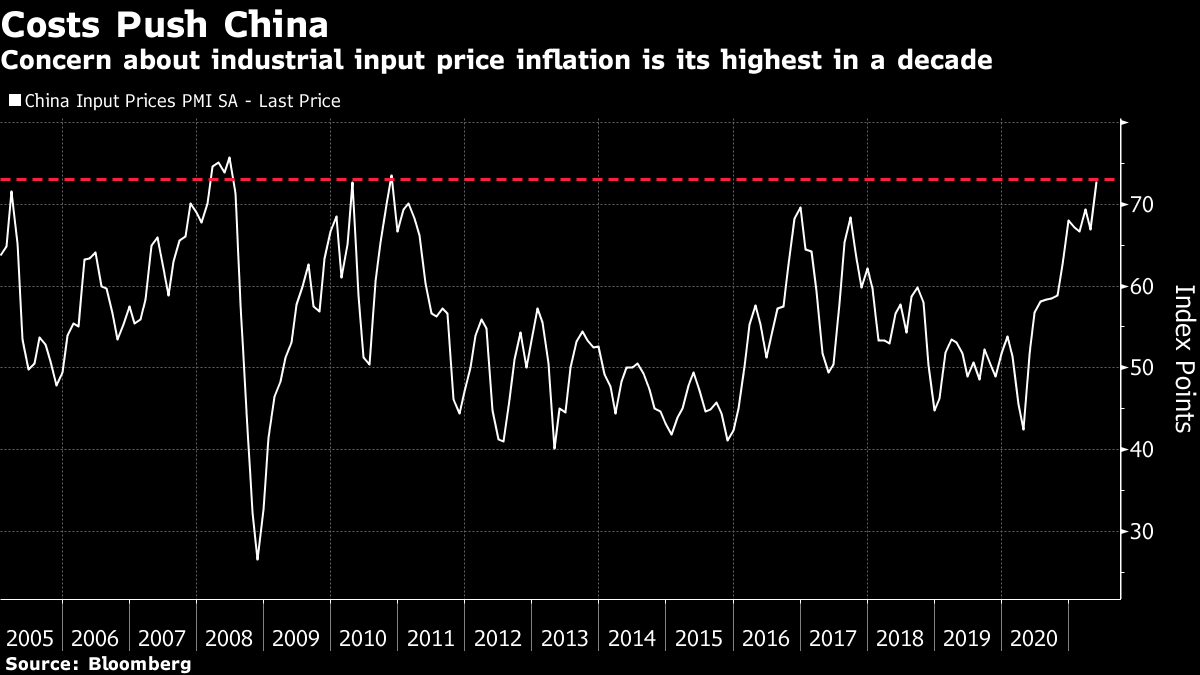

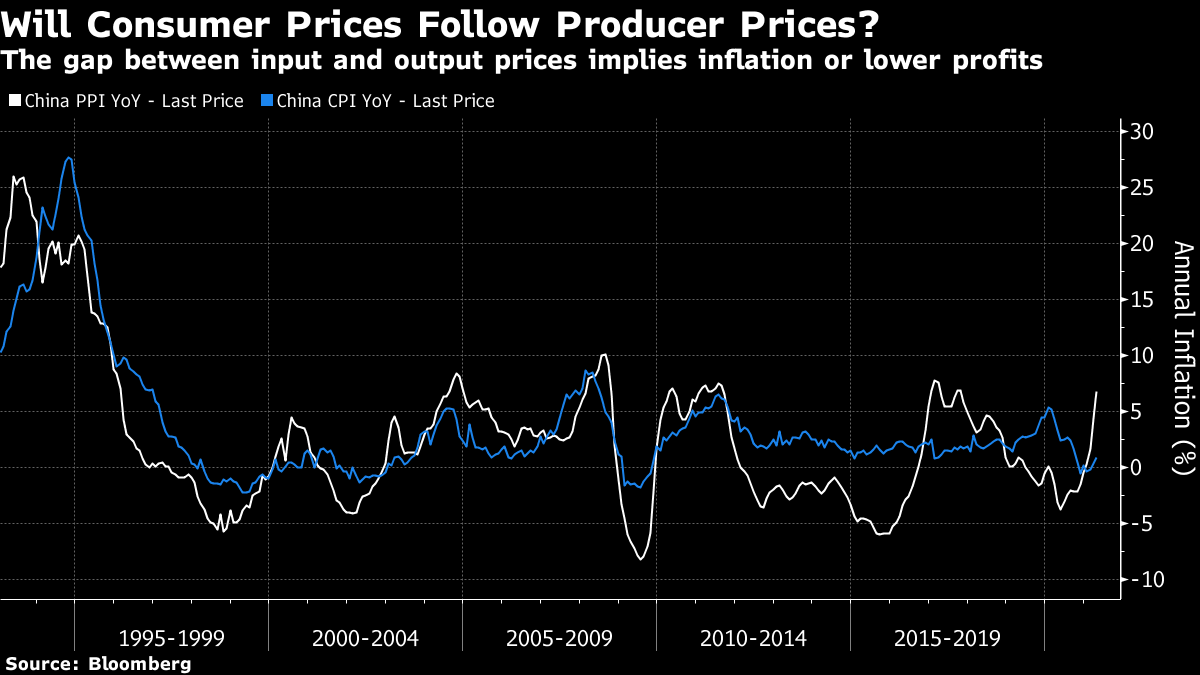

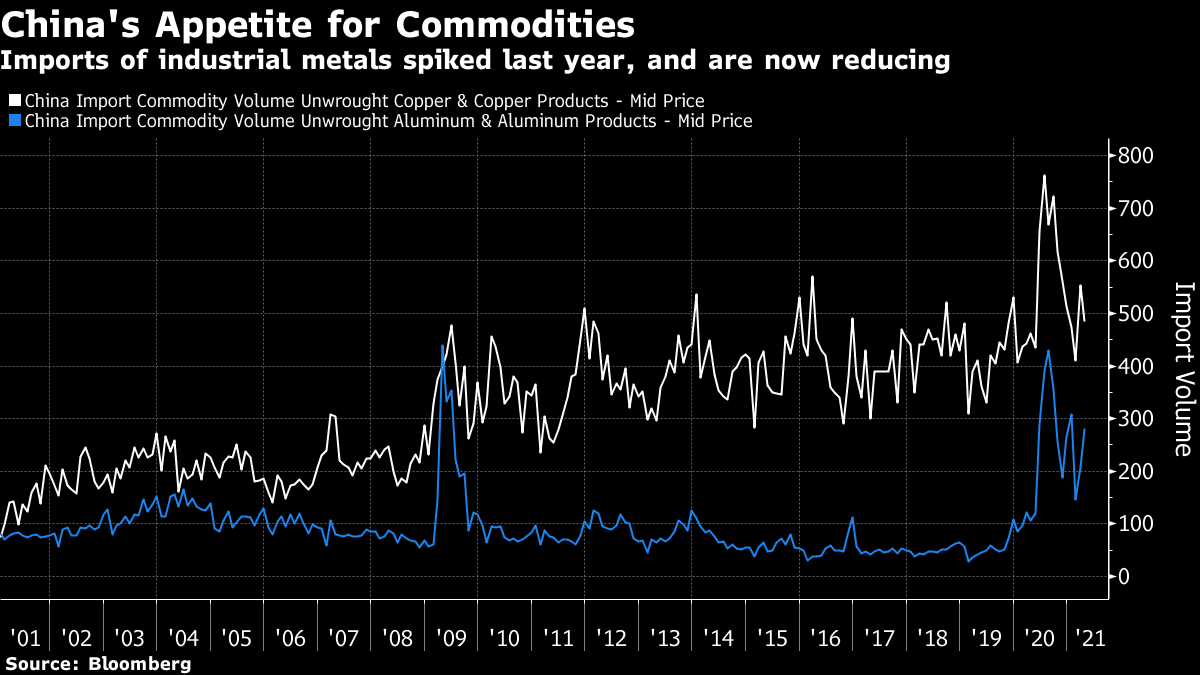

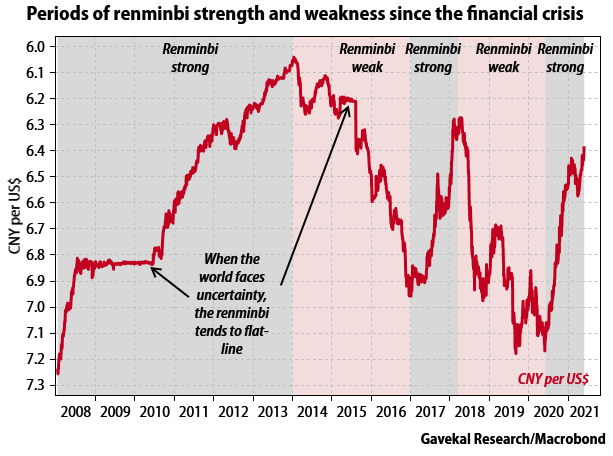

Inflation: The Eastern FrontAs the start of the month brings its usual deluge of data, it may be best to look first to the East. China has an inflation issue of its own, and it could drive the rest of the world. The country's latest PMI survey of supply managers showed that the number concerned about rising input prices was the highest in a decade:  Unlike previous periods of heavy producer price inflation, however, this time there is no particular expansion in consumer prices as yet. The gap between China's PPI and CPI is its highest since the early 1990s:  Logically, this can only be dealt with in two ways. Either companies can increase prices, meaning higher consumer price inflation in due course (classic cost-push), or they can eat the higher input costs, and suffer a fall in profits. Neither option is appetizing. It should be no surprise that prices are rising, however: Last year saw massive Chinese demand for industrial metals, as the leadership pressed the customary pedals to reignite growth. This chart shows the volume of aluminum and copper imports over the last two decades:  In terms of the amounts of metals consumed, then, this was a boom even greater than the splurge of spending with which China helped lift itself (and much of the rest of the world) out of the global financial crisis in 2009. How might the Chinese authorities deal with this situation? One logical approach would be to try to clamp down on commodity speculation, which they did last week. Another would be to let the currency appreciate. This would make import prices cheaper, and thus reduce inflation. It would also attract funds and goods to China. The last year has indeed seen a dramatic rise in the renminbi. As the following chart from Gavekal Research shows, it has done this even though the global economic situation remains volatile and uncertain. In previous times of heightened economic tension, the authorities decided that discretion was the better part of valor and kept the currency stable:  All else equal, a stronger Chinese currency means a weaker U.S. dollar, with all that that entails. Most importantly, for now, this could portend a period in which China exports inflation to the rest of the world, just as it arguably exported deflation in the 1990s and 2000s when the entry of the nation's workforce to the world market at an artificially cheap exchange rate helped keep a check on prices everywhere else. The problem with a stronger currency would be competitiveness, and China's weekend announcement that banks must increase the amount of foreign currency they hold in reserve looks a lot like a signal that the authorities would like the appreciation to stop. It's also not at all clear that the authorities know their own mind on this — China may act as a monolith in the final resort, but there is plenty of disagreement behind the scenes that the rest of us don't get to see. How else might we expect the Chinese leadership to react? A fascinating piece by Gavekal's Louis Gave attempts to derive the likely psychology of the current leaders from their upbringing. They spent their youth under Mao Zedong, and had their fill of Marxist orthodoxy. Counterintuitively, this might make them very anxious to avert rising inflation: all Chinese leaders were raised in the Marxist church. And the first tenet of this faith is that historical events are shaped by economic forces (rather than individuals or ideas), with inflation being among the most powerful. For Karl Marx, Louis XVI would have kept his head and his throne, had it not been for rapid food price inflation in the years before France's revolution in 1789. And for a Chinese technocrat, the Tiananmen uprising of 1989 only happened because, at the time, inflation was running above 20%.

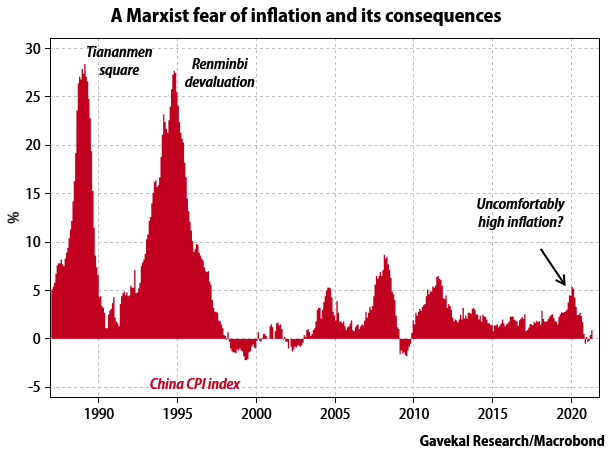

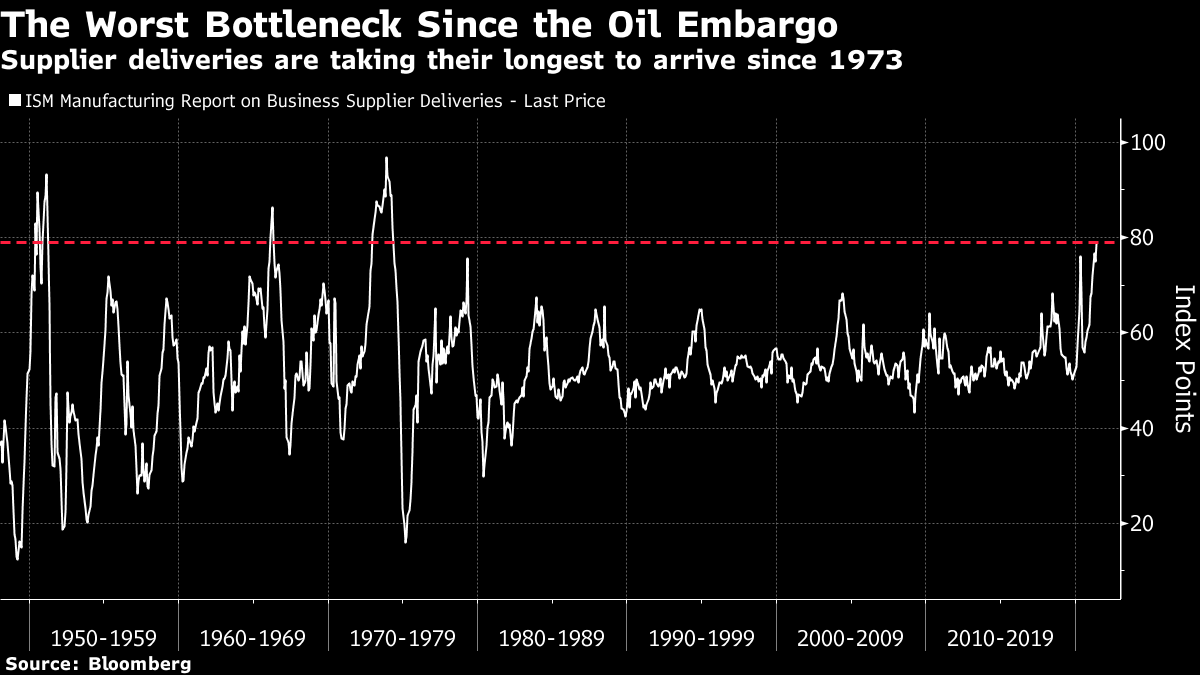

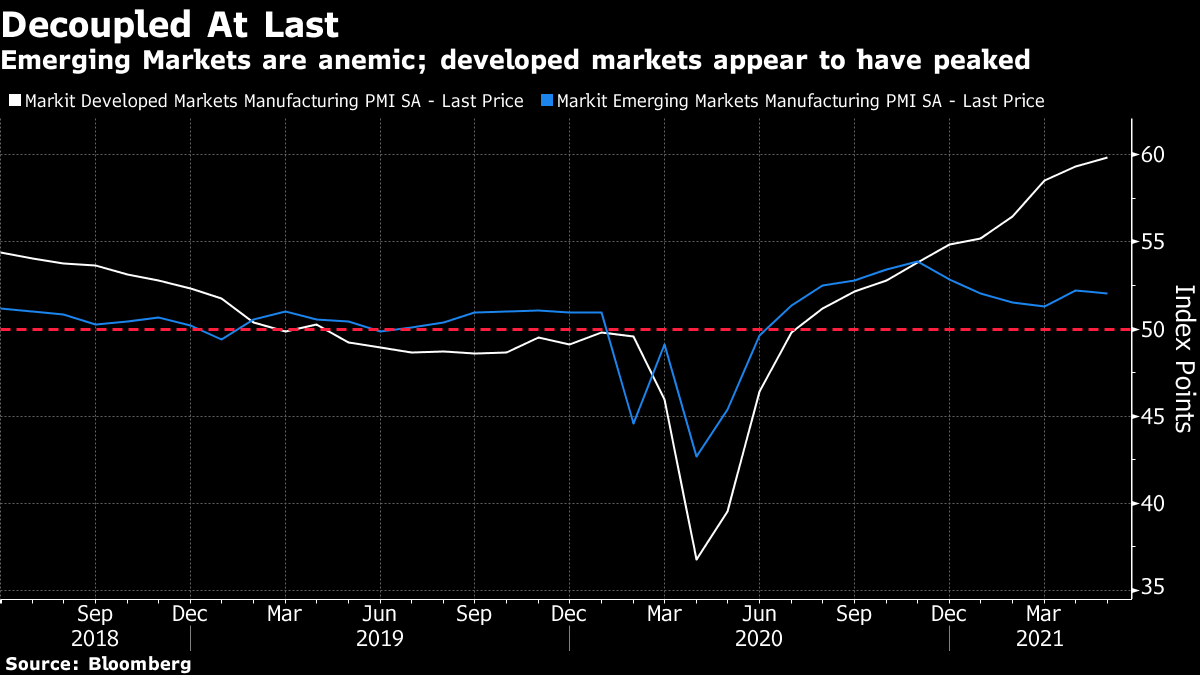

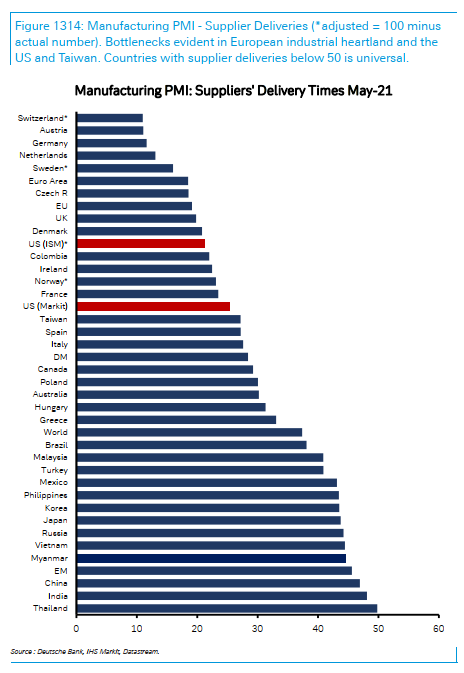

As this chart from Gave shows, the Tiananmen massacre of 1989 followed a period of extreme inflation, while China's devaluation a few years later, as Deng Xiaoping opted for a policy of aggressive growth, brought another awful price spike in its wake. The degree to which it has kept headline inflation under control since then, against the background of historically impressive growth, is remarkable. It suggests that China's leaders really, really want to avoid higher inflation:  On this basis, the People's Bank of China is the latter-day Bundesbank, dedicated to eradicating inflation when all others are more relaxed about it. A look at the change in M2, a broad measure of the money supply, in comparison with the same number for the U.S., also suggests something of a role reversal. Here is year-on-year M2 growth for the two economies, going back to 1996:  Unsurprisingly, money supply has grown far faster in China than in the U.S. for most of the last 25 years, because its economy has been growing much more rapidly. The spikes in the 1990s, as its export-driven model was revving into gear, and again in 2009, when it did everything it could to lift the economy out of crisis, were sights to behold. And remarkably, what happened in the U.S. to deal with Covid-19 was almost as dramatic. Meanwhile, the relative conservatism of China's monetary response has been surprising throughout the pandemic period. Again, this suggests the leadership will go to some lengths to avoid inflation. The significance for the Western world would be twofold. First, if China is a less enthusiastic buyer of stuff, it could mean slower global growth. And second, if it exports inflation as it once exported deflation, it creates a very distinct extra problem for the rest of the world. Turning away from China, the monthly publication of manufacturing PMIs, all set so that 50 should be the dividing line between expansion and contraction, is always a great time to take the temperature of the economy. It may be transitory, but the most eye-catching development from the welter of data was the number for problems with supplier deliveries in the U.S. The last time it was this high came in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War and the subsequent oil embargo of late 1973. The Covid-19 shutdown felt like a comparably big interruption to business at the time, and so it has proved to be. The question is how quickly the bottlenecks can be cleared:  Another issue, highlighted by Deutsche Bank AG's strategist Alan Ruskin, is the divergence between the developed and emerging worlds. Generally, over the last few decades, emerging markets have been a geared play on the West. They have outperformed on the way up, and underperformed on the way down. The bull market in EM assets in the years before the crisis was driven by the thesis that they had reached a point of "decoupling," where they could grow unhindered by events in the developed world. Instead, this cycle has brought us to the point where they have decoupled in the other direction. The developed world has recovered far more sharply, if we follow the composite manufacturing PMIs offered by JPMorgan Chase & Co.:  There is ample room for this to correct over the next few months, as the developed world appears to be peaking, while emerging markets should be able to move forward from here. If developing economies have a problem with growth however, this at least means less of a problem with supply bottlenecks. The following graphic, produced by Ruskin, inverts the usual measure of supply problems in the ISM, so that it accords more with intuition; he subtracts the official number from 100, so that a lower number shows a worse problem with supply delays. On that basis, the bottleneck turns out to be truly global, but it is a curse of the developed world far more than of emerging countries still in the worst throes of the pandemic. Indeed, it appears to be afflicting the nations at the heart of industrialized western Europe worse than anywhere else. The base case should be that these delays will prove transitory; but they certainly add to the notion that the developed world has more of an inflation problem on its hands:  What we need to avoid is a vicious cycle. Ruskin lays out what that might involve: The vicious cycle... is captured in this US anecdote that is also relevant for many other countries: "In an effort to protect against future supply shortages, firms increased their input buying activity markedly. Pre-production inventories were built at the fastest rate on record, but stocks of finished goods fell further as holdings were used to supplement production." Supply side shortages, are driving a scramble for inputs to protect against future shortages. This scramble is exacerbating supply shortages, and likely will for at least the next few months. Just in time inventories is being forsaken. Stocks of finished goods are below normal for all but three countries, and some normalization here will be a signal for the easing of supply side pressures.

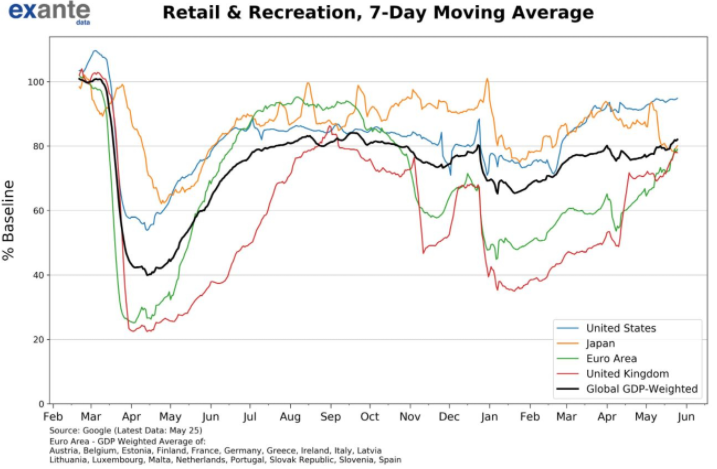

When it comes to the risk of global cost-push inflation, this is the key issue for the next few months. It should prove transitory, and the data are perfectly consistent with a more positive story in which the developed world exits the slowdown first, largely thanks to the vaccine, with the emerging world following later. That is still the most likely scenario. The risks center on supply bottlenecks, and China's attempts to avoid inflation. An Olympic-Size ProblemThe pandemic never ceases to agonize and surprise. Japan is due to host the Olympics, starting next month, giving the world its first great global event since Covid-19. Since March last year, Japan has been the least disrupted of the world's biggest economies. Yet now, on the eve of the games, the nation is more affected by the pandemic than most of the developed world. That is the conclusion of the latest Google data on mobility.  Judging by Google's information, charted here by Exante Data, Japanese use of retail and recreation facilities is as low as it has been in 12 months. It lags the U.S., which is now beginning to allow spectators into mass sports events, and is at parity with Europe, where crowds are still limited. For a long time, it looked as though Japan would be the ideal venue for a classic games, generating all the excitement that comes with a passionate home crowd. Now, just as the games are about to start, that is no longer the case. The ability of the virus to hit just where it isn't expected and just where it causes the greatest hurt continues to be uncanny. The fate of the games now stands to be central to sentiment about reopening across the world. If Tokyo somehow stages a great Olympiad despite myriad last-minute doubts, as London did nine years ago, the sense that normality is back will be that much stronger. If the games take place in empty venues, or suffer last-minute withdrawals or cancellations due to Covid-19, then not so much. Survival TipsOn the subject of the Olympics, there's nothing like them. I was living in London when it hosted the 2012 games, and the experience was magical (and not just because the organizers decided to hold the entire event to a backdrop of British songs from my youth, like Enola Gay, London Calling, Going Underground, and Heroes). There are always bound to be moments of drama, but best of all are the controversies. Whose fault was the collision between Zola Budd and Mary Decker in 1984? Was it really necessary for Kerri Strug to go through with her second vault in 1996? Why did the whole U.K. decide it was so great that a myopic ski-jumper should take up everyone's time in 1988? And later that year there was the dirtiest race of all time. It would be good to get another dose of this next month. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment