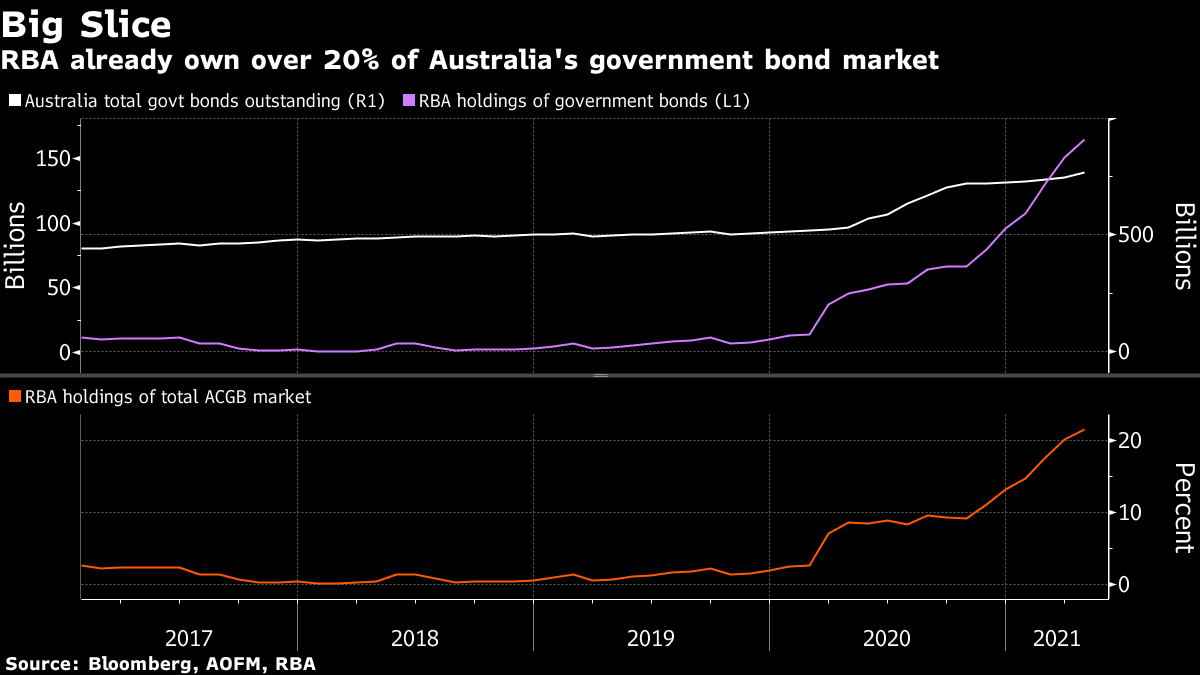

| Welcome to The Weekly Fix, the newsletter that suspects the taper tantrum will be tweeted. — Emily Barrett, cross-asset reporter/editor Passing the BatonFor a while there, shorting core European government bonds was the new widow-maker trade. Not anymore. Europe is taking the lead in the great government bond selloff that swept the world earlier this year. As yields in the U.S. steadied from a rapid ascent in the first quarter, those on German Bunds continue to climb. Appetite for German debt has soured notably, judging by recent auctions. Germany's sale of 10-year bonds this week met the coolest reception in over a year. Mounting expectations for a pullback in that support, and soon, are at least partly to blame for the rout. It's getting harder for the European Central Bank to justify pandemic-era policy settings as the vaccine rollout picks up, along with economic data. So far it's stuck to the global central bankers' script that the recent boost in price pressures is temporary. But judging by the more hawkish comments from the head of Germany's central bank, Jens Weidmann, it may be harder to ignore consumer prices heading above target in the country that's close to its centenary of hyperinflation. And with Germany's elections just four months away, some see politics also contributing to the bond market's woes. There's talk of Bunds suffering in line with rising expectations for heavier government spending as the Greens gain in some polls versus outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel's conservative alliance. This handing of the recovery/reflation baton to Europe has driven a rotation of sorts among investors in the world's major sovereign markets. Kellie Wood, fixed income portfolio manager at Schroder Investment Management, is among those who've shifted their underweight positions across the pond, from the U.S. to the U.K. and Europe. "The ECB is going to be at a point where yields are moving up alongside very healthy growth and inflation outcomes, which we have not seen in Europe for decades and decades," she said.  Goldman Sachs expects the ECB to announce a "modest" taper of purchases under its pandemic program at the June meeting. It's also among the more aggressive in its forecast for the rise in German yields -- saying the 10-year could hit 0% in the third quarter, if not sooner. The majority of strategists responding to Bloomberg's latest survey see Germany's 10-year yield turning positive, for the first time in two years, around the third quarter of 2022. The Eye of the BeholderSo where does this leave rates in the world's largest bond market? Still treading water, despite the strongest monthly rise in consumer price inflation since the '80s, at last count. Nevertheless, some of the keener observers have a more anxious interpretation. Markets are "rightly worried" about the Fed's tolerance, according to Bloomberg Opinion columnist and Allianz SE chief economic adviser Mohamed El-Erian. And possibly woefully unprepared for what could be a reset higher for the whole curve, if you ask Bill Dudley. The former New York Fed president reckons the central bank will have to raise its target interest rate to 3% or higher to curb inflation in the coming years, and the 10-year yield could top 4% if the government pushes on with deficit financing. For now, we're in a holding pattern. Taper talk in the U.S. has gone off the boil somewhat, with a little help from a surprisingly weak non-farm payrolls release early this month. That took some of the sting out of the subsequent release of the minutes from the April meeting, in which some officials apparently said "it might be appropriate at some point in upcoming meetings to begin discussing a plan for adjusting the pace of asset purchases." Some seized upon that blindingly obvious comment as a cue to sell, but it was notable only in the sense that the topic may be becoming more approachable -- albeit not necessarily more pressing -- among policy makers. Positioning in this environment is a tough call, as recovery trades have largely stalled in the U.S., with credit spreads still relatively tight and liquidity still ample. "The one risk premium that's really changed -- and it's acknowledged in the way that central banks implement policy -- is term premium. So curves are steeper, way steeper," says Robert Mead, who's co-head of Asia-Pacific portfolio management at Pimco. "One of our strategies globally at the moment is to have some curve steepening positions on pretty consistently," he said, which fits with "an environment where there's some uncertainty about the path and speed of the recovery."  So the great taper debate rolls on. And it has stirred some controversy in the more austere reaches of the Fintwit-tersphere. Adam Posen of the Peterson Institute for International Economics argued that the Fed is still a long way from tapering, and sees a move less than four months ahead of a hike in the first half of 2023. That view got some pushback from Robin Brooks, chief economist of the International Institute of Finance, who says the market conditions are ripe for a taper. That is, the combination of an improving growth outlook and low levels of the 10-year real yield are reminiscent of 2013, just before then-chairman Ben Bernanke dropped the hint that sparked the 'taper tantrum'. A wager may have been struck, so we'll have popcorn with our Jackson Hole webcams. And here we turn to our rates guru Stephen Spratt, who's looking to the next step in the great global policy unwind... How Slow Can You GoTaper talk has landed in Australia, but the economic data will decide how far the discussion gets. The central bank has lined up its July meeting as probably the event of the year. Policy makers will decide on the next steps for bond buying and whether to extend the yield curve control program to a new three-year bond, and thus extending its commitment to low rates. A slowdown of purchases is very much in the cards. The government budget last week pointed to a drop in funding needs as pandemic support programs roll off, so fewer bonds need to be sold. Fewer bonds sold means fewer bonds need to be bought by the central to have the same supportive impact. Put simply, it's more bang for the... Well, Aussie dollar. What's more, the central bank already owns more than a fifth of the bond market and that share keeps rising every week. The Reserve Bank of Australia's deputy governor, Guy Debelle, said in a speech earlier this month that RBA is mindful that its bond purchases don't cause market dysfunction by taking up too much of it. And so, the writing is on the wall.  The economy's progress toward the RBA's goals of full employment and sustainable inflation will of course determine the pace of any reduction in bond purchases. The latest labor market report, released this week, looked on the surface like a setback on that front, with employers cutting jobs in April instead of the expected gains. This may not be as bad as it seems. First, the Easter holiday was during the main reference period, and appears to have influenced the report. Second, April was the first full month after the nation's flagship job support programs, creatively named JobKeeper, had expired. If these muddying factors pass and employment revs back up, then the July tapering may turn out to be a question of how slow can they go. Bonus PointsThe not-so new guard at Morgan Stanley World's superstar firms get bigger, techier, and more Chinese $ASS Coin billionaire: Tales from the fringe of the crypto craze And a gripping tale from the Snap Judgment vault: Ocean vigilantes hunt the most notorious poacher on the high seas |

Post a Comment