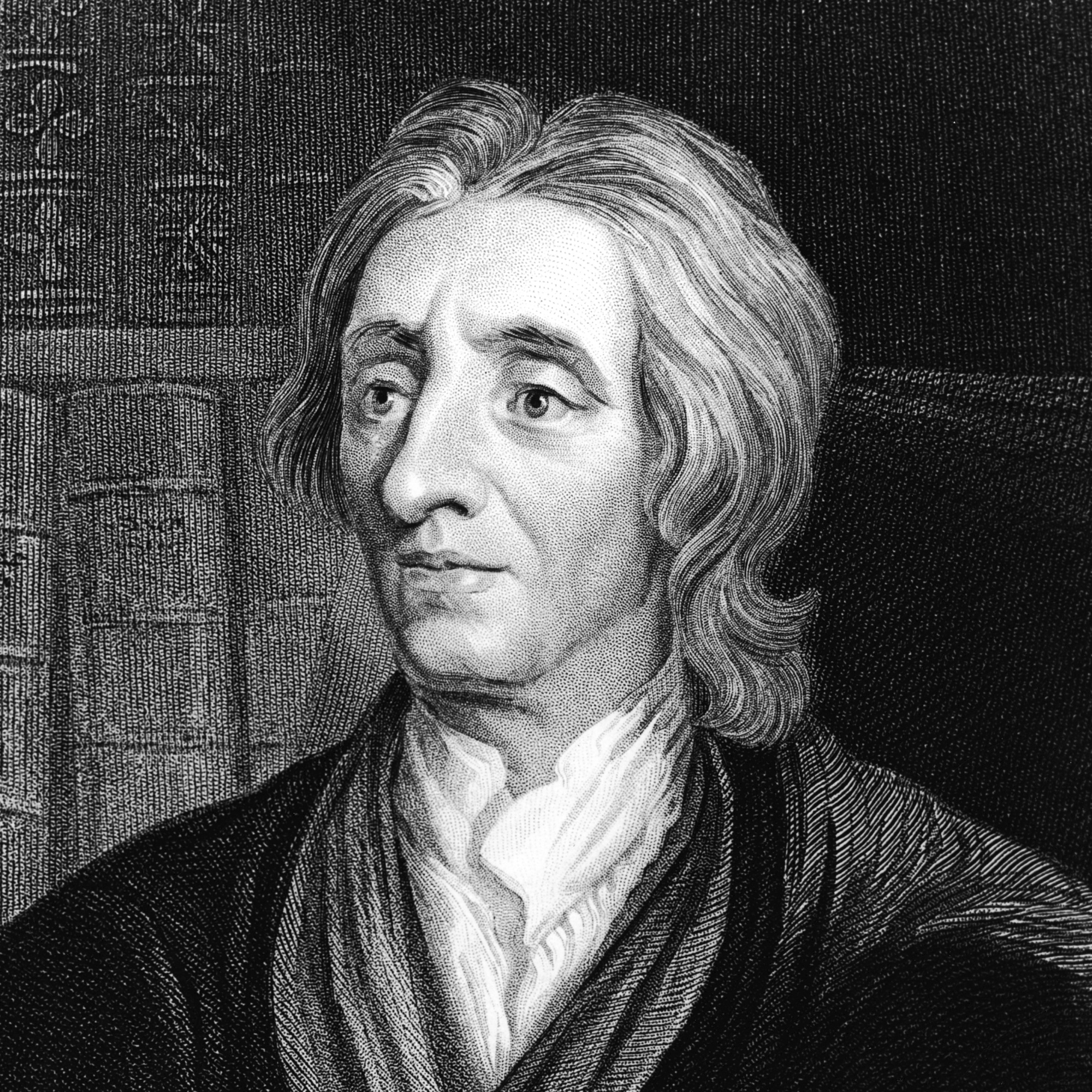

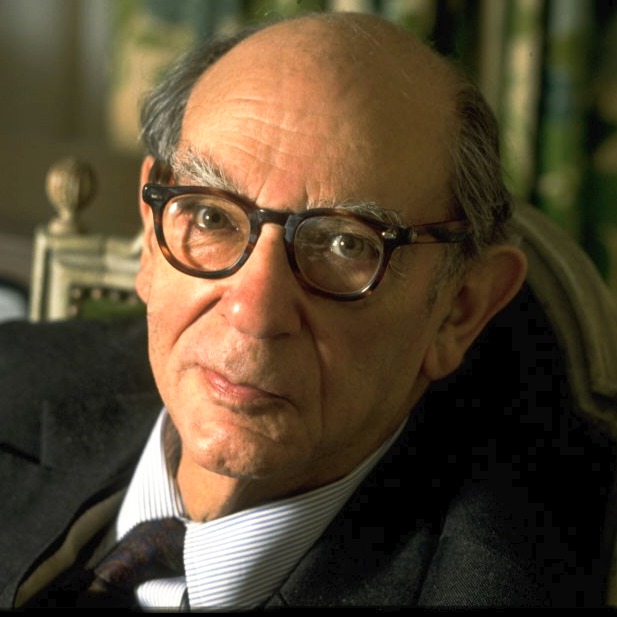

| Welcome to Sunday morning. This is a special Points of Return to continue the occasional series on CoronaValues: the ethical issues that the pandemic raises, and the difficulty that we have all experienced in dealing with them. A previous essay looked at the ethics surrounding vaccines. This one looks at what the pandemic has revealed about conceptions of freedom, and what happens when the values of life and liberty come into conflict. I hope it makes for an interesting weekend read. Feedback is most welcome. The conflict is right there in the opening words of the document that founded the United States of America. Everyone has a right to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Few would disagree with Thomas Jefferson's declaration of principle. But what happens when life and liberty come into conflict? Plainly, liberty must have some limits. And the coronavirus pandemic, posing a threat to life that can only be fought by collective actions to which some won't consent, revealed that few in the Western world knew where to put those limits, or even what they meant when they talked of liberty. China, whose dominant Confucian philosophy emphasizes life and social harmony, showed how much easier it was to protect life if governments could ignore individual liberties. In January of 2020, after a cluster of coronavirus cases emerged in the province of Hebei, which surrounds Beijing, authorities declared a "wartime state" once the case count reached 600. What followed was a literal lockdown. Some 20,000 residents of outlying villages were bussed to government quarantine facilities. People in three cities with a combined population of 17 million had to stay in their buildings at all times. All 11 million residents of the provincial capital, Shijiazhuang, had two compulsory Covid-19 tests each week. Men in hazmat suits marched through empty streets spraying disinfectant. Apartment doors were taped shut from the outside after authorities dropped off vegetable packages to last five days. Many homes lacked fridges or ovens. By the end of the month, the number of cases had topped at 865. Train service re-started after a 34-day gap. Things returned to normal. This is what happens if life trumps liberty. In the West, where it doesn't, there were onerous but more lenient stay-at-home orders, which generally ended before outbreaks had been extinguished. On March 2, a month after the Hebei lockdown, Governor Greg Abbott of Texas announced that his state was "100% open." Abbott admitted that Covid-19 remained a risk, but declined to impose further infringements on liberty. "Each person has a role to play in their own personal safety and the safety of others," he said. "With this executive order, we are ensuring that all businesses and families in Texas have the freedom to determine their own destiny." Texas had reported 7,750 new cases in the previous week. Texas is a famously individualist state, but was not an outlier. The lockdowns of 2020 were well enough observed to cause a savage economic recession, but provoked intensifying opposition. The universal theme was that freedoms had been violated. In a viral video, a shopper entered a Costco warehouse in Colorado without a mask, and was asked to put one on because that is the company's policy. "I'm not doing it because I woke up in a free country," replied the shopper, who complained that mask-wearers were "sheep" as the attendant took away his trolley. In the U.K., a multi-party group called "Keep Britain Free" led protests on behalf of "millions of people who want to think for themselves and take responsibility for their own lives." Banners at violent demonstrations in Germany proclaimed, "Freedom isn't everything, but without freedom, everything is nothing." There were arguments over whether lockdowns would work against the disease, and whether their heavy economic toll was justified. But the central point remained: Most Westerners felt the Hebei lockdown was immoral even though it successfully beat the virus, because it violated people's freedom. The ends didn't justify the means. But if liberty is so important, what exactly is it, and where does it come from? John Locke and Natural Rights Liberty has a surprisingly recent heritage. Neither the ancient Greeks nor the Jewish prophets had any great concept of it, nor do any of the great Asian traditions. Instead, the doctrine of a right to be free dates to the ferment in 17th-century England that saw one king executed and another dismissed. The country rejected the notion of an absolute monarchy operating by divine right, and the philosopher John Locke offered a new system to replace it.  John Locke Source: Hulton Archive via Getty Images Locke believed in natural rights to life, liberty and property. But for men to be free, he saw that they must allow others to be free. Thus, in his formulation, freedom did not include a right to "harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions" and included an obligation to "preserve the rest of mankind." That would seem to exclude the freedom to ignore doctors who warn against the risk of infecting fellow citizens with Covid-19 by leaving the house, refusing to wear a mask or refusing a vaccination. Striking the right balance between individual freedom and social obligation has been the aim of philosophers ever since. As Locke's ideas became the founding philosophy of England's rebel colony, but not of Locke's home country itself, defining the right to liberty that he promulgated has been the central debate within the U.S. throughout its history. It has proved maddeningly difficult. Sixty years ago, the Oxford University professor Isaiah Berlin, who fled the Soviet Union with his family when he was a child, made a famous speech defining two concepts of liberty. The first was "negative" liberty: freedom from interference, the freedom to be left alone. This is the version that drove Jefferson and the other founding fathers. The "Don't Tread on Me" flag of a coiled rattlesnake, adapted by Benjamin Franklin as an emblem of resistance in the War of Independence, is now the flag of American resisters against pandemic restrictions.  Isaiah Berlin Photographer: Sophie Bassouls/Sygma Berlin also saw a rival concept of "positive liberty," the freedom to do what one wants. This is what French revolutionaries meant when they called for "liberty, equality and fraternity." This notion of freedom motivated left-wing lockdown opponents, who held that quarantines were unfair to those who could not afford to go without income, and couldn't work from home. They were effectively deprived of their positive liberty.Those were the kinds of people who gained support from the Harvard philosopher John Rawls who published his massive "Theory of Justice" in 1970. Rawls imagined a social contract that people would sign behind a "veil of ignorance," in which they did not know where they would rank in society. At great length, he argued that citizens would happily tolerate some degree of inequality, but that the worst off would have to be in an acceptable position. Put differently, everyone needs some positive liberty to have the chance to make something of themselves. Such thinking justifies governments in clamping down on liberty in a pandemic, particularly if they pay money to those who lose their jobs as a result. Such a policy held sway, with regional variations, across the West. Opposition to anti-Covid measures, from lockdowns to vaccines, has been dominated by negative, not positive liberty. George Crowder, a philosopher at Flinders University in Australia and author of several major books on Berlin, described it as the American revolutionary philosophy writ large. "I think these protests are just basically about negative liberty," he said in an interview. "It's people wanting to do what they want to do and wanting government to get out of their way." Berlin himself opposed positive liberty, fearing that it could become a Trojan horse for the kind of totalitarianism he witnessed in his youth. His last essay, published after his death in 1997 by the New York Review of Books, rang with the distrust of science that surfaced a quarter-century later: There have always been thinkers who hold that if only scientists, or scientifically trained persons, could be put in charge of things, the world would be vastly improved. To this I have to say that no better excuse, or even reason, has ever been propounded for unlimited despotism on the part of an elite which robs the majority of its essential liberties.

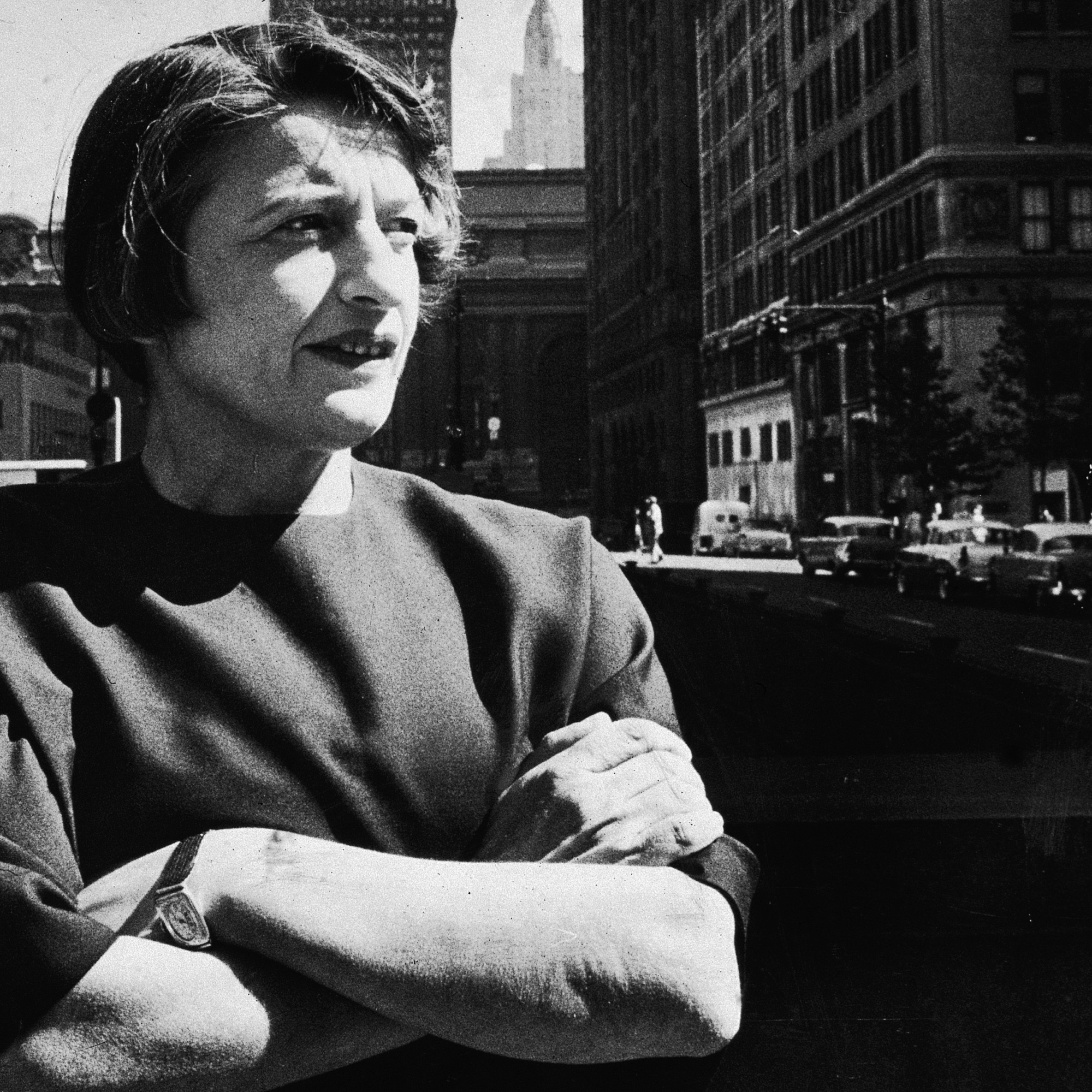

The last year's protests, then, have been an expression of a yearning for negative liberty. People expect to be left alone. But this entails leaving others alone, and that creates another set of problems. Ayn Rand and Modern LibertarianismLibertarians on the political right take Locke's notions of natural individual rights to their logical conclusion. Hugely influential in the U.S., where they have exerted a strong influence on the Republican Party, modern libertarians hold either for a limited state restricted to national defense, policing and safeguarding of contracts, or no state at all.  Ayn Rand Source: New York Times Co./Getty Images Its most famous exponent is another Russian emigre philosopher, Ayn Rand. Her acolytes included Alan Greenspan, who spent 18 years as chairman of the Federal Reserve starting in 1987, while Paul Ryan, a former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, based policy proposals on a speech by a character in Rand's novel "Atlas Shrugged." These ideas underpinned Reaganomics, tax cuts, school vouchers and other policies to shrink the state. But when fighting a pandemic, even rock-ribbed libertarians acknowledge limits to liberty. Milton Friedman, the Nobel prize-winning economist and impassioned libertarian, accepted a role for the state in dealing with "neighborhood effects," when the actions of one individual impose costs on others. He wrote in the 1950s that these "justify substantial public health activities: maintaining the purity of water, assuring proper sewage disposal, controlling contagious diseases." Others made no such concessions. Murray Rothbard, another libertarian economist of Friedman's generation, developed a theory of "anarcho-capitalism" that held that the state itself was illegal, along with taxation. "For this philosophy, saving lives is of no moment," Walter Block, a libertarian economics professor and follower of Rothbard, wrote in the Journal of Libertarian Studies last year. "Rather, the essence of libertarianism concerns rights, obligations, duties, the nonaggression principle, and private property rights." Block argued that if libertarian rights are always respected, more lives would ultimately be spared. Rigorous libertarian arguments lead to some surprising places. Since libertarians must respect property rights, the hapless Costco customer who refused to wear a mask inside the privately owned store would have had little support from Rothbard or Rand. And even lockdowns are complicated for those who treat the liberty of others as seriously as their own, creating controversy among libertarians. The right to walk down the street with a gun in a holster would not extend to firing it at random without running afoul of the non-aggression principle so familiar to libertarians that they give it a nickname, NAP. What does the NAP imply in a time of contagious disease? Rothbard worried that the NAP might be misused to justify an over-active state, and warned in his book "The Ethics of Liberty" that force should not be used against someone just because his or her behavior is "risky": Once one permits "someone's fear of the 'risky' activities of others to lead to coercive action, then any tyranny becomes justified," he wrote. But other libertarians are prepared to countenance a different balance in a pandemic, and remain agnostic on quarantines. "If spreading illnesses is not a rights violation, then nothing is," Block wrote in the Journal of Libertarian Studies. Libertarians are often accused of justifying selfishness, and Rand even wrote a book called "The Virtue of Selfishness." But the arguments that say the state shouldn't tell people what to do might also imply an obligation to voluntarily wear masks and observe social distancing. Liberty is a two-way street. Unmasked protesters gathering in large crowds under rattlesnake flags might not have thought this one through. Delimiting LibertyAfter a year of anger, the West is no closer to defining the limits of liberty. Most countries ended up with compromises that satisfied nobody, with lockdowns tough enough to inflict misery but not to thwart the disease from claiming a dreadful toll. That failure is dispiriting, and governments' actions during the pandemic leave legitimate reasons for anger and protest. But even though liberty became a rallying call, it's not clear that its adherents knew what liberty they wanted, or even whether liberty was what they wanted at all. Crowder, the philosopher and Berlin chronicler, has probably thought about liberty as much as anyone now living. He put it this way: "A lot of people abuse the idea of liberty and they present it as a fine sounding concept that in fact is just a placeholder for something else that concerns them or bothers them. It's a fine sounding placeholder for saying that they will do what they want to do and get out of my way." |

Post a Comment