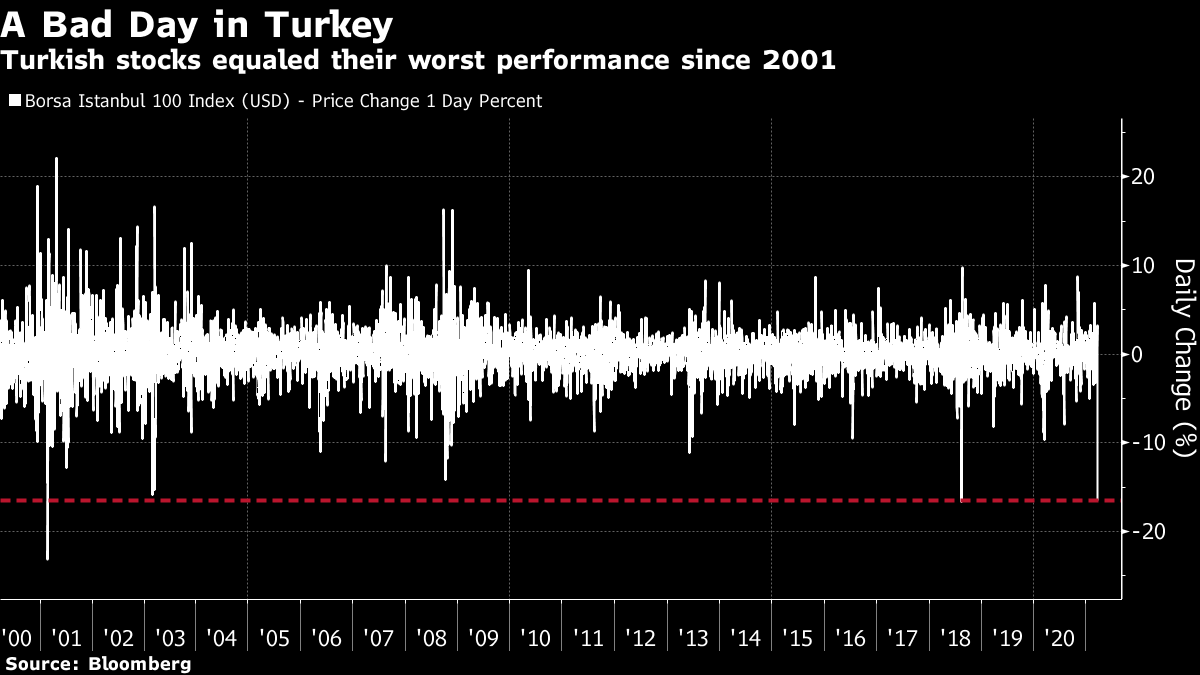

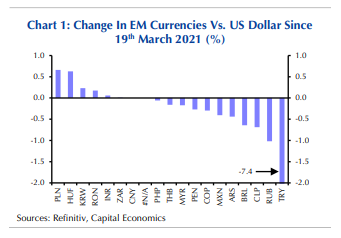

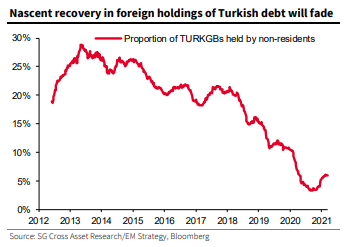

Turkish DelightRecep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey's increasingly autocratic premier, inflicted a vintage emerging markets crisis on us over the weekend. Four months after ousting his previous central bank governor, he fired Naci Agbal, who had raised rates by 200 basis points last week, and replaced him with Sahap Kavcioglu, who apparently agrees with Erdogan's novel theory that higher interest rates cause inflation. It's plenty possible to be an effective political leader while having eccentric views about economics — but not if you are able to fire and replace central bankers at will. International capital markets didn't like this. Turkey's lira tanked, as did the stock market. In dollar terms, Istanbul's main benchmark equity index fell 16.4%, exactly equal to its performance on the day three years ago when then President Donald Trump ordered sanctions on the country. Its only worse day this century came in early 2001 when the lira was floated, in an effective one-off devaluation, as it was Turkey's turn to suffer from a contagious series of emerging market devaluation crises:  It's hard to call this an overreaction. Turkish economic policy appears to be fully under the control of an unchecked autocrat who doesn't understand economics. International markets like central bank independence, particularly when the country is governed by someone they might otherwise dislike. A number of other emerging economies, such as Mexico and Brazil, have managed to avoid serious financial crises in the last two decades, despite electing some market-unfriendly populist presidents, by maintaining central bank independence. As U.S. bond yields have risen in the last few weeks, and emerging markets have suffered the capital flight that is customary on these occasions, independent central banks have acted as a shock absorber. Their credibility has also enabled them to keep rates lower than in Turkey. Brazil's real has suffered even more than the lira since the beginning of last year, and the country saw a drastic 75 basis point rate hike of its own last week. But Brazil has a target rate of 2.65%, while Turkey's is 19%. Russia, which also hiked last week, has a target rate of 4.5%. Rate increases in other large emerging markets show that higher U.S. yields have caused generalized pressure. The critical point is that Turkey is seen as an idiosyncratic situation. Erdogan's actions haven't spilled over into problems elsewhere in the foreign-exchange market. Indeed, Bloomberg's index of eight emerging market carry-trade currencies, which includes the lira, was up on Monday:  Put differently, Capital Economics of London shows that the lira was an outlier over the weekend. There are no falling dominoes this time:  Turkey accounts for only 3.5% of JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s EMBI Global Diversified index, so there should be minimal contagion via bondholders. General distrust had prompted international investors to sell off their holdings of Turkish bonds. That had shown some signs of reversing in the last few months, as this chart from Societe Generale SA shows, but the latest news has likely snuffed out that enthusiasm:  Spain's banking system has the biggest exposure to Turkey, at $59.7 billion, according to Bank for International Settlements data, though that's a fraction of Spain's total banking assets of about $3.36 trillion. The debate now is over how Turkey opts to stem the weakness in its currency. As the new governor is likely to try to undo the latest 200 basis point rise in rates, the chance is that the lira will come under renewed fire. The preliminary consensus among foreign-exchange analysts seems to be that capital controls will be the most likely solution, given that Erdogan has shown he cannot tolerate increasing borrowing costs. According to Sebastien Galy, economist at Nordea Investment: The new governor promises permanent price stability but also believes as president Erdogan does that interest rates lead to inflation, against economic orthodoxy. The next meeting is set for the 15th of April where at least 2% in interest rate cut is to be expected. The bigger problem is that with extremely low foreign reserves and a large current account deficit, the currency falls if it is not supported by high enough interest rates. In real terms, they were only 3% as inflation is around 16%. Any cut below 3% in interest rates would lead to more weakness in the currency and likely capital controls. All of this is of course unhelpful for affiliates of some European banks.

Phoenix Kalen of SocGen maps out a route in which Turkey treats the world to all the classic steps of an emerging market crisis — which means that it will lose in the end: The new CBRT Governor Kavcıoğlu has expressed in a statement on the central bank's website that future MPC meetings will be held as scheduled, meaning no imminent emergency rate cut meeting between now and the 15 April 2021 MPC meeting. Our very preliminary expectation is that the new governor will attempt to undo the latest 200bp hike at the 15 April meeting, deploy substantial reserves between now and then to try to stabilize TRY, subsequently lose the currency battle with markets, and ultimately have to engage in emergency hikes down the road to halt [the lira]'s decline.

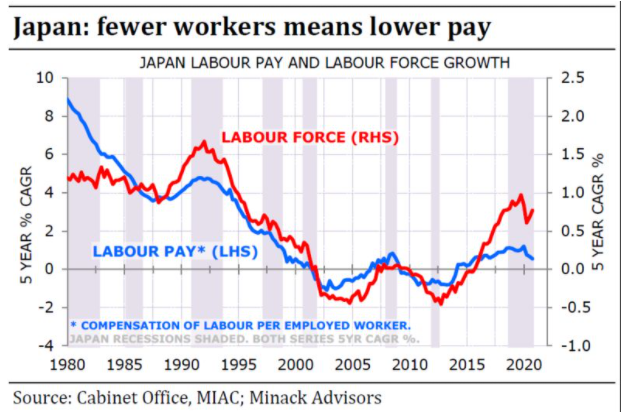

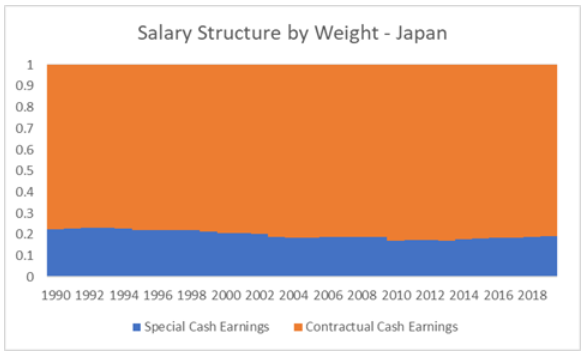

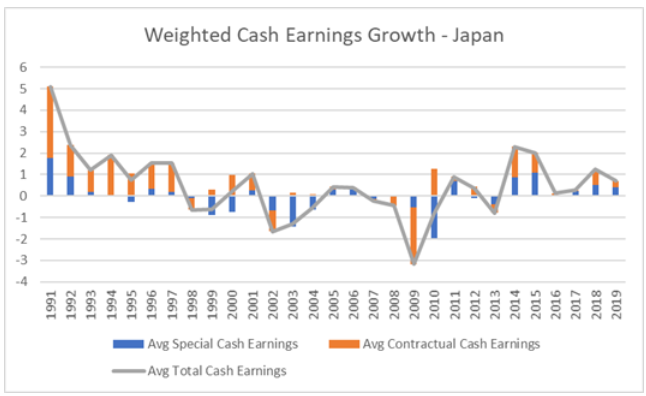

All of this is very sad for Turkey, but the contagion is unlikely to spread further, unless other countries start to elect Erdogans of their own. Stickiness in JapanIf there are fewer workers, they should have greater negotiating power, and so they can win higher wages — which will likely spill over in the long term into inflation. Except in Japan, the country which has to date had the greatest experience of ageing, and where the labor force has shrunk relative to the growing number of retirees. That is a summary of a debate I covered yesterday. Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan argued in The Great Demographic Reversal that the forthcoming shrinking of the workforce across the Western world would help inflation to re-establish itself. Gerard Minack argued in response that Japan's history suggested a shrinking workforce was no guarantee of inflation. This was his killer chart:  This is startling, but powerful empirical evidence that we don't after all need to fear a new wage-price spiral as the labor force contracts. We can expect Goodhart and Pradhan themselves to re-enter the debate before long. In the meantime, I received an important argument about the Japanese experience from Philip Pilkington of GMO in Boston. He suggests that Japan might be a special case. The reason gets to the heart of one of the most important issues in labor market economics; nominal wages are "sticky." In other words, employers can generally get away with cutting pay in real terms, after inflation, but it is almost impossible to get a workforce, unionized or otherwise, to accept an outright nominal reduction. This means that when workers manage to win a good increase in good times, it is very hard to claw it back from them in bad times. That isn't necessarily the case in Japan, though. This is because workers are paid via a bonus system that is unusual elsewhere outside of finance. As this chart from GMO shows, about 20% of Japanese salaries are "special cash earnings" or bonuses:  So Japanese employers can cut pay and get away with it — and have done so several times over the three decades since the country began to sink into its deflationary malaise. Thanks to the heavy bonus element, total cash earnings have varied widely in that time, even as consumer prices have been stuck:  This process makes life much easier for employers, and leads to great pay days in good times. It also allows for deflation to take hold. As the average Japanese worker has a "pay packet that looks very like that of a finance professional," to quote Pilkington, companies can avert the risk of having to pass on rising labor costs to consumers via higher prices. The lack of wage-stickiness has thus helped to trap Japan in deflation. This is Pilkington's conclusion: So, what does this mean for the demographic inflationary hypothesis? Well, it means that Japan is a special case. Most countries do not rely as heavily on bonuses to compensate workers as Japan does. This means that there is far more stickiness in their wages. Perhaps when the demographic collapse begins in earnest Western economies will find some way to maintain extreme wage flexibility – although this will lead to deflationary problems like the ones Japan experiences. However, it seems more likely – to me at least – that they will see bargaining power tip in favour of labour. That probably means inflation.

Does anyone out there have anything to add to this discussion? If, as I suspect, the answer is "yes," please let me know. Aphorisms of a Stock OperatorIn readiness for the book club live blog on Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, at TLIV on the terminal at 11 a.m. New York time Wednesday, take your pick of my attempt to cull its best five turns of phrase. And if you've read the book: Who do you think the hero Jesse Livermore (Larry Livingston in the book) is most like? I've heard suggestions that he's a proto-George Soros or Steve Cohen, or that he worked out behavioral finance almost a century before Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky. I've also heard him nominated as an early version of Bernie Madoff, which I think is unfair. Any suggestions? Now for some aphorisms: "In speculation when the market goes against you you hope that every day will be the last day — and you lose more than you should had you not listened to hope — to the same ally that is so potent a success-bringer to empire builders and pioneers, big and little. And when the market goes your way you become fearful that the next day will take away your profit, and you get out — too soon. Fear keeps you from making as much money as you ought to. The successful trader has to fight these two deep-seated instincts. He has to reverse what you might call his natural impulses. Instead of hoping he must fear; instead of fearing he must hope. He must fear that his loss may develop into a much bigger loss, and hope that his profit may become a big profit. It is absolutely wrong to gamble in stocks the way the average man does." "There is nothing new in Wall Street. There can't be because speculation is as old as the hills. Whatever happens in the stock market to-day has happened before and will happen again. I've never forgotten that. I suppose I really manage to remember when and how it happened. The fact that I remember that way is my way of capitalizing experience."

"It takes a man a long time to learn all the lessons of all his mistakes. They say there are two sides to everything. But there is only one side to the stock market; and it is not the bull side or the bear side, but the right side. It took me longer to get that general principle fixed firmly in my mind than it did most of the more technical phases of the game of Stock speculation."

"If the unusual never happened there would be no difference in people and then there wouldn't be any fun in life. The game would become merely a matter of addition and subtraction. It would make of us a race of bookkeepers with plodding minds. It's the guessing that develops a man's brain power. Just consider what you have to do to guess right."

"I have found that experience is apt to be a steady dividend payer in this game and that observation gives you the best tips of all. The behavior of a certain stock is all you need at times. You observe it. Then experience shows you how to profit by variations from the usual, that is, from the probable." Survival TipsAs Turkey is getting a bad press today, a couple of reminders that Istanbul is still one of the world's most wonderful cities. First, watch James Bond, accompanied by Miss Moneypenny, smash it up in the opening scene of Skyfall; and then watch from a cat's eye view in the wonderful documentary Kedi, about the city's stray cats. Two great pieces of escapism. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment