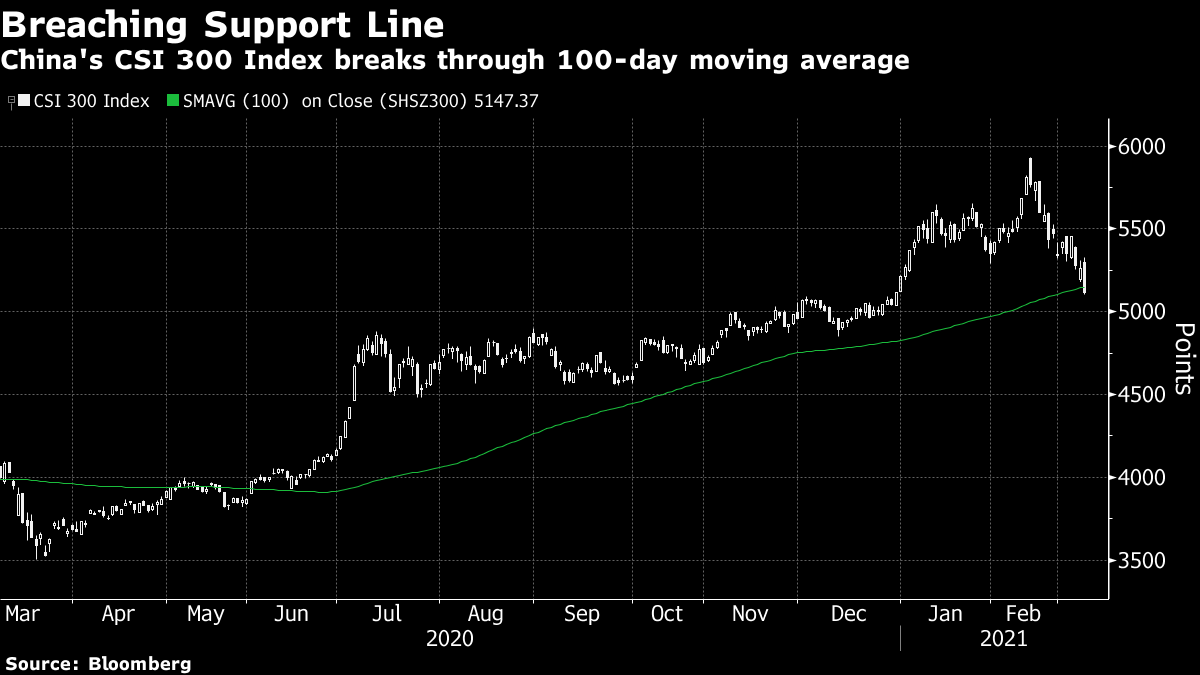

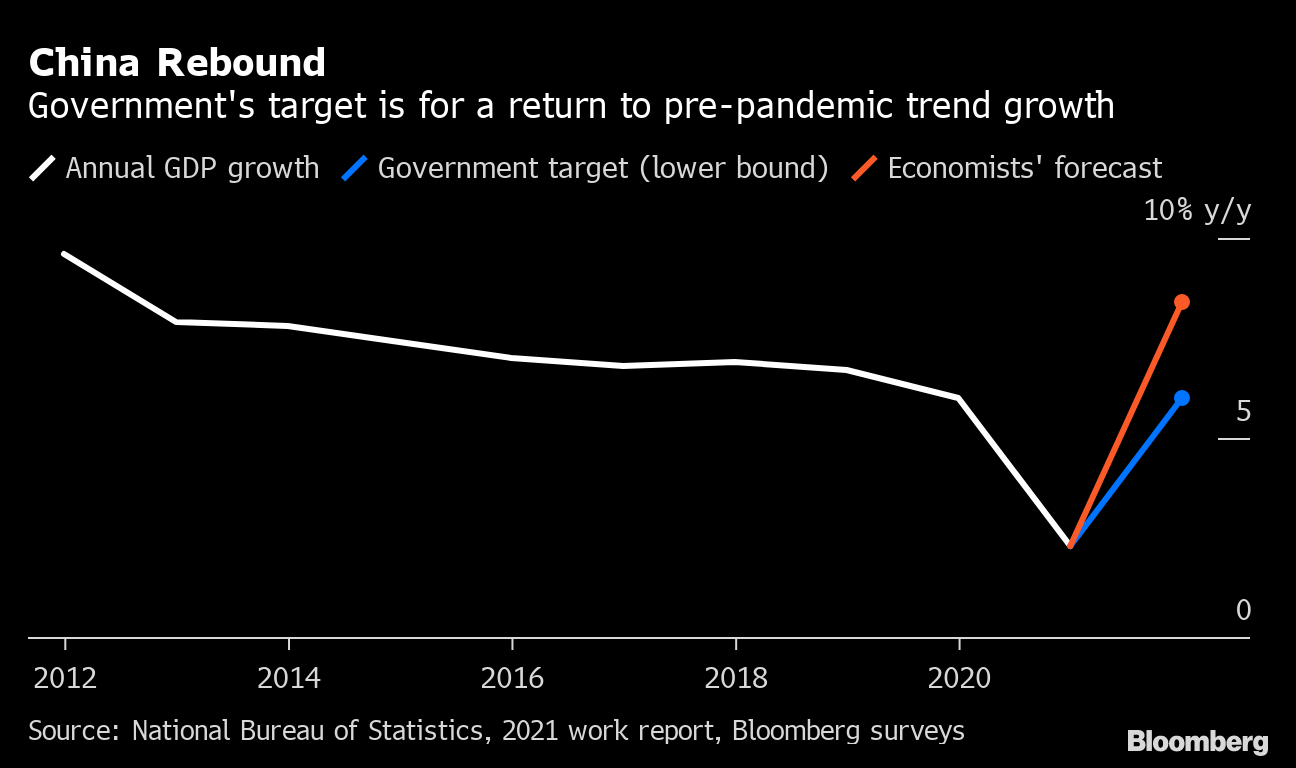

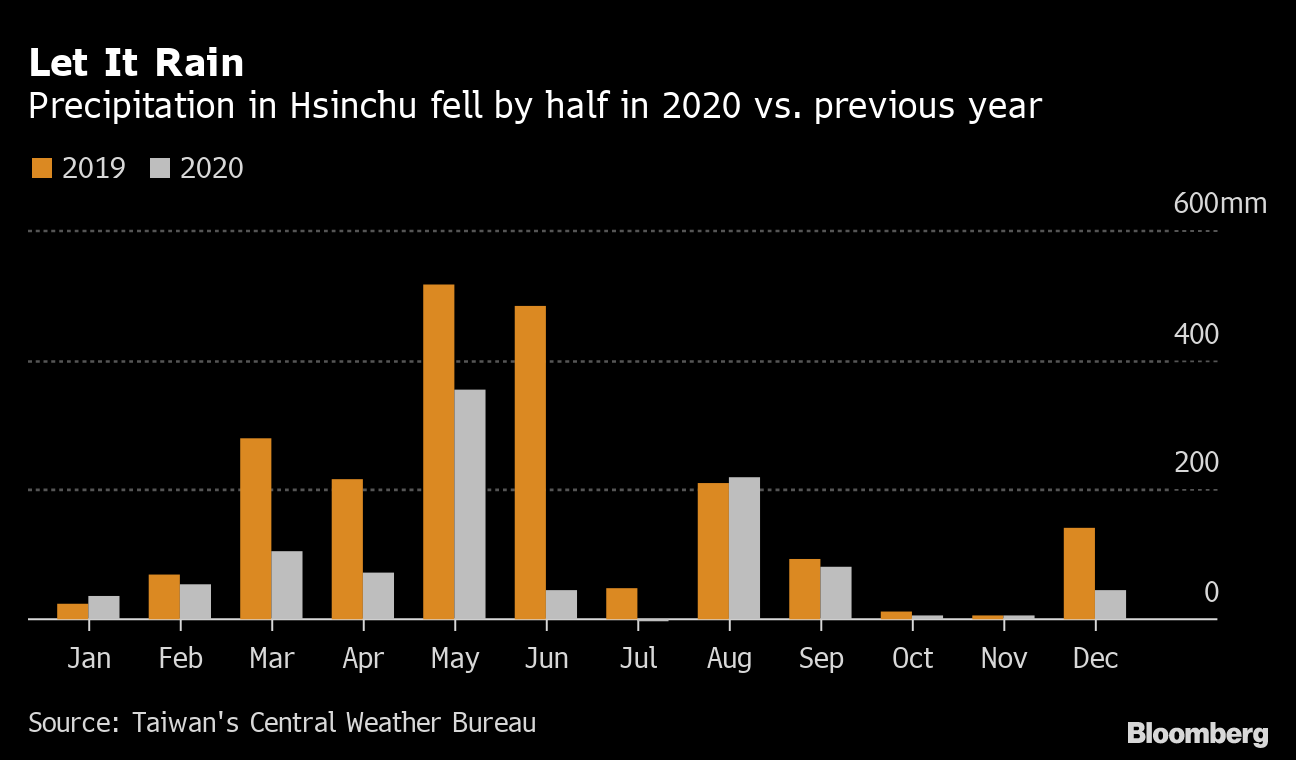

| When stock markets have eye-popping surges, they are often followed by equally dramatic plunges. What sets China apart is how it manages the journey down. History suggests Beijing has fewer reservations about intervening in financial markets than most other major economies. That's not to say such actions are exclusive to China. During the global financial crisis, for example, governments around the world banned shortselling in a bid to stabilize their markets. France, South Korea and Indonesia banned the practice last year as Covid-19 rattled their economies. Intervention in China, however, is not always linked to crises. The hand of the state can also be present during important dates on the political calendar, when the country's leaders are keen to avoid unpleasant distractions. This week offered an interesting example of that phenomenon. Rattled by signs that Beijing is intent on withdrawing stimulus introduced to counter the economic effects of Covid, China's benchmark stock index has plummeted more than 5% since March 1. Most of those declines have notably come as China's top leaders gathered in Beijing for the annual full session of the country's parliament, the National People's Congress. This year's NPC is especially notable for the unveiling of the five-year plan that outlines economic priorities through 2025. Not an ideal time for a stock-market swoon, to say the least. By Tuesday, with the main index having fallen through its 100-day moving average, it seemed Beijing had seen enough. That's when state funds began buying in a bid to stabilize the market.  There was more. On Wednesday, Chinese authorities also took steps to mute the volume of public discourse that the selloff was generating. Weibo, the Chinese social media platform that's similar to Twitter, began blocking searches for the term "stock market." The service, though, didn't purge all references to the plunge, allowing users to still query for posts about "stocks" and "A-shares," a reference to companies listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen. And now that the NPC has concluded, the question of how China's policy makers will manage markets going forward is just as intriguing. There's no guarantee that Beijing will intervene if the declines continue. If the past is any guide, there will be plenty of voices arguing for a light touch, just as they did during China's dramatic stock market crash in 2015. That debate, which revolved largely around whether a plunge in share prices posed a systemic risk, contributed to what was at times a choppy response from Beijing. The same questions still resonate six years later, though the back and forth may not last too long. In less than four months, China's Communist Party will be commemorating the 100th anniversary of its founding, a celebration Beijing will want to see go off without a hitch. Not Aiming LowOne of the more surprising things about this year's NPC was China setting its target for economic growth in 2021 at above 6%. By comparison, the median estimate in a Bloomberg survey of economists is for expansion of 8.4%. Asked at his annual press conference about the conservative target, Premier Li Keqiang argued that 6% is not low, given the uncertainties that still remain about China's recovery and the global economy. He also emphasized that what Beijing wants is quality growth, not rapid expansion, and signaled authorities would be scaling back stimulus measures introduced last year. Li's comments offered quite a contrast to what was happening in the U.S. this week, where President Joe Biden signed a $1.9 trillion pandemic relief bill. The different paths that the world's biggest economies appear to be on is not only a reflection of how they've handled the pandemic, but also the different lessons each took from the global financial crisis. Whereas a stunted and choppy U.S. recovery after 2008 left many in Washington concluding that it's vital to "go big" on stimulus and keep it flowing, the debt problems caused by the massive stimulus China introduced at the time have left many in Beijing believing sometimes less is more.  Face to FaceTop officials overseeing foreign affairs for the U.S. and China are set to meet next week in Alaska for what will be the highest-level in-person discussions since Biden took office. Beijing's delegation will be led by Yang Jiechi, a member of the 25-person Politburo, and Foreign Minister Wang Yi. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan will be the principle American participants. There'll be plenty to talk about. Among the trickier issues are Beijing's grip over Hong Kong, the Uyghurs in Xinjiang and America's position on Taiwan. But there's also just as much discord over technology, supply chains, Covid and trade. Speaking publicly about these matters, officials from both countries have tended to focus on how the other side should change. It's hard to imagine those positions being significantly softer in private. But Beijing and Washington have also each pointed toward areas for potential cooperation, climate change being the most-often mentioned. Reopening closed consulates and ending a spat over journalist visas are two issues that have been raised as relatively easier topics that could help build confidence if resolved. Expecting great changes in the relationship after one meeting would be naïve. Looking for signs of progress is something many will be doing.  U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken speaks during a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing in Washington on March 10, 2021. Photographer: Ting Shen/Bloomberg Hong Kong ElectionsOne issue that's likely to come up in Alaska is the overhaul of Hong Kong's electoral system that was ratified this week in Beijing. Not only is it a subject where the American and Chinese positions are far apart, but it's also one that's set to be in headlines throughout the year. With the full session of the NPC approving the proposal, it will now be up to the body's standing committee to flesh out the details for how the city's elections will be reconfigured. That process will take months to complete and be the subject of much interest throughout. Then as the year draws to a close, the looming election for seats on Hong Kong's Legislative Council will again put the spotlight on the overhaul and whether Beijing has effectively silenced the city's political opposition. Hong Kong seems destined to be a pain point for U.S.-China ties for some time. Chips Await RainThe month of May became far more economically important this week after Taiwan's Minister for Economic Affairs said the hub for global semiconductor production has enough water to keep its chip plants humming until then. Monsoon rains usually arrive in Taiwan in May, which should spell an end to the island's worst drought in 56 years. If the rainfall is substantially less than expected, however, there will be much hand-wringing in Taipei and around the world. A global chip shortage has already forced carmakers to idle plants and pushed governments to re-evaluate their supply chains. It has led the U.S., Germany and other countries to press Taiwan to ramp up production. But with chip-making being so water-intensive and so much of it happening in Taiwan, the future of the global semiconductor supply chain will ultimately depend in large part on the weather.  What We're ReadingAnd finally, a few other things that caught our attention: |

Post a Comment