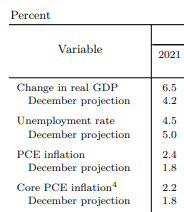

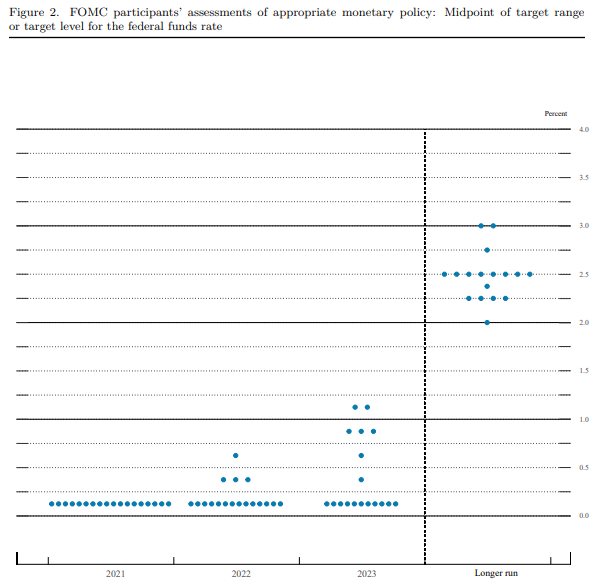

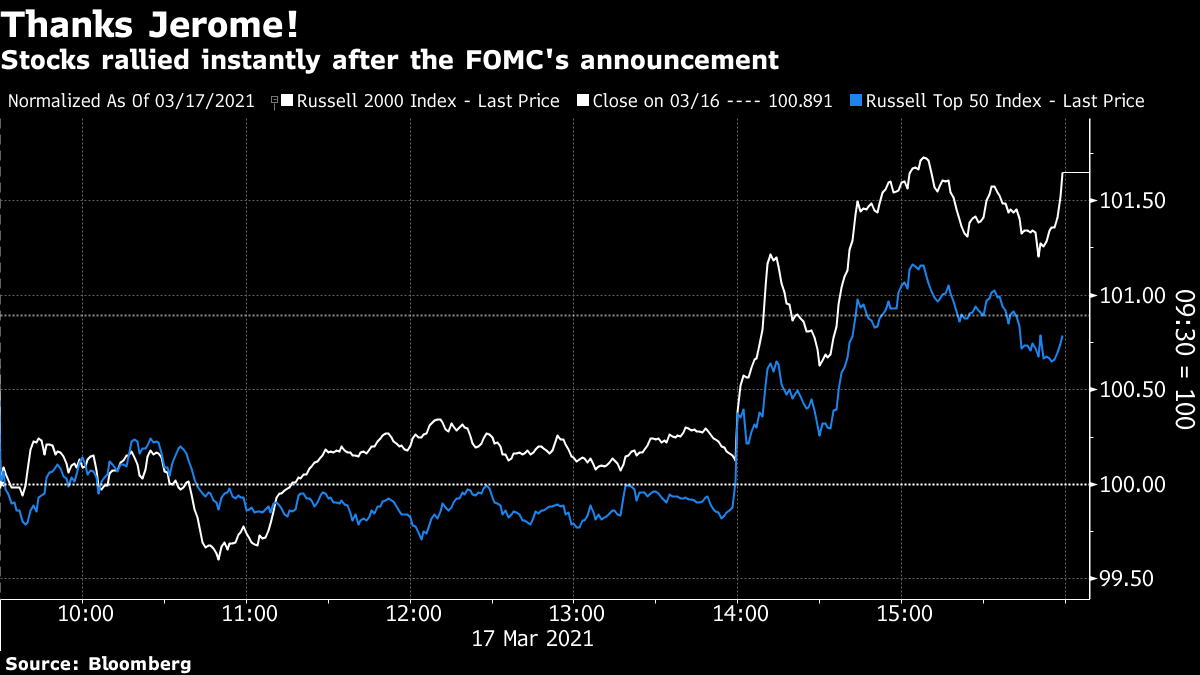

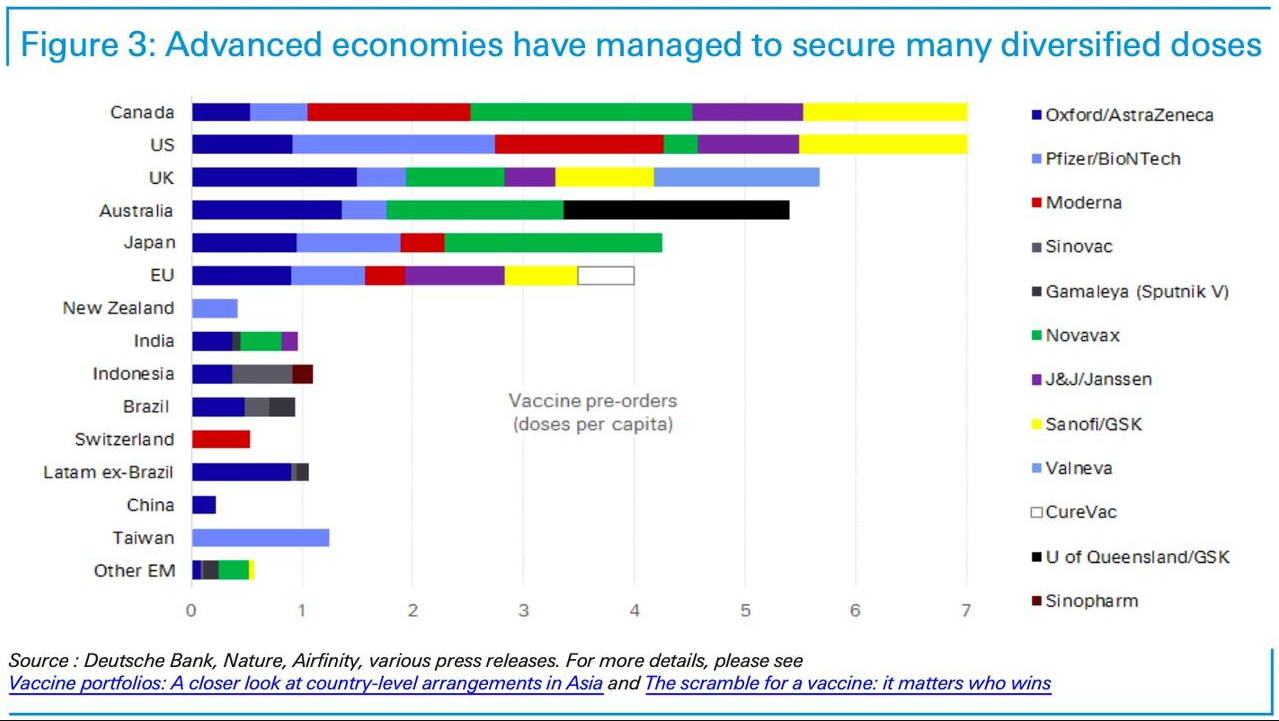

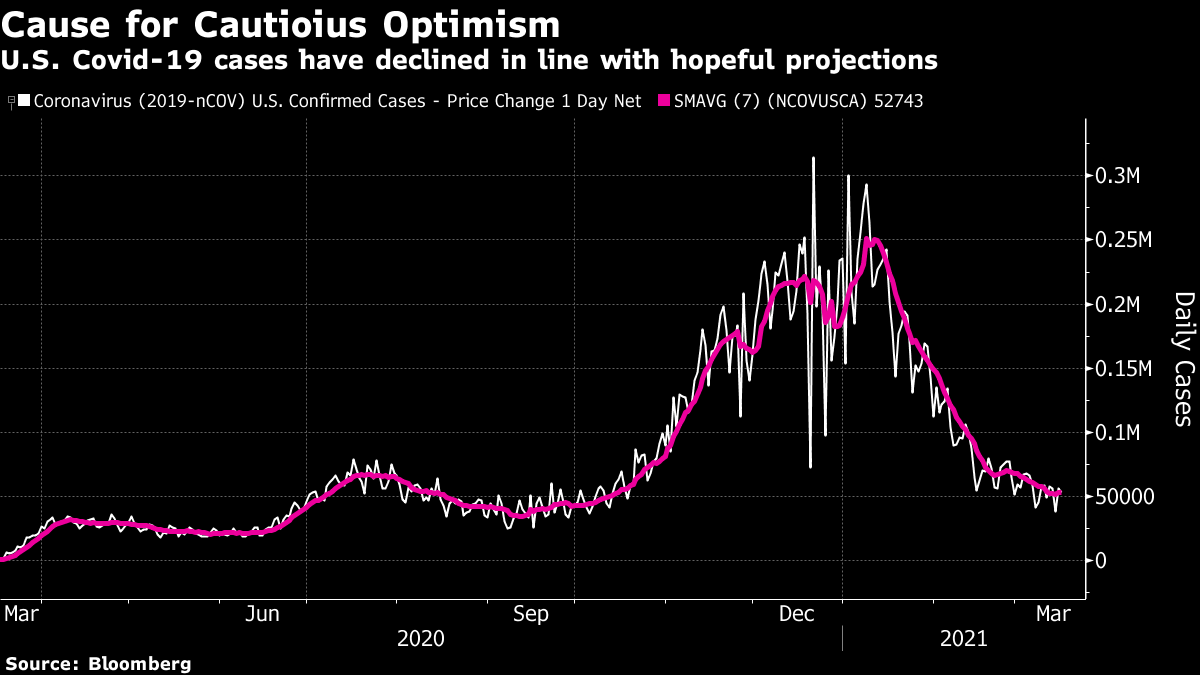

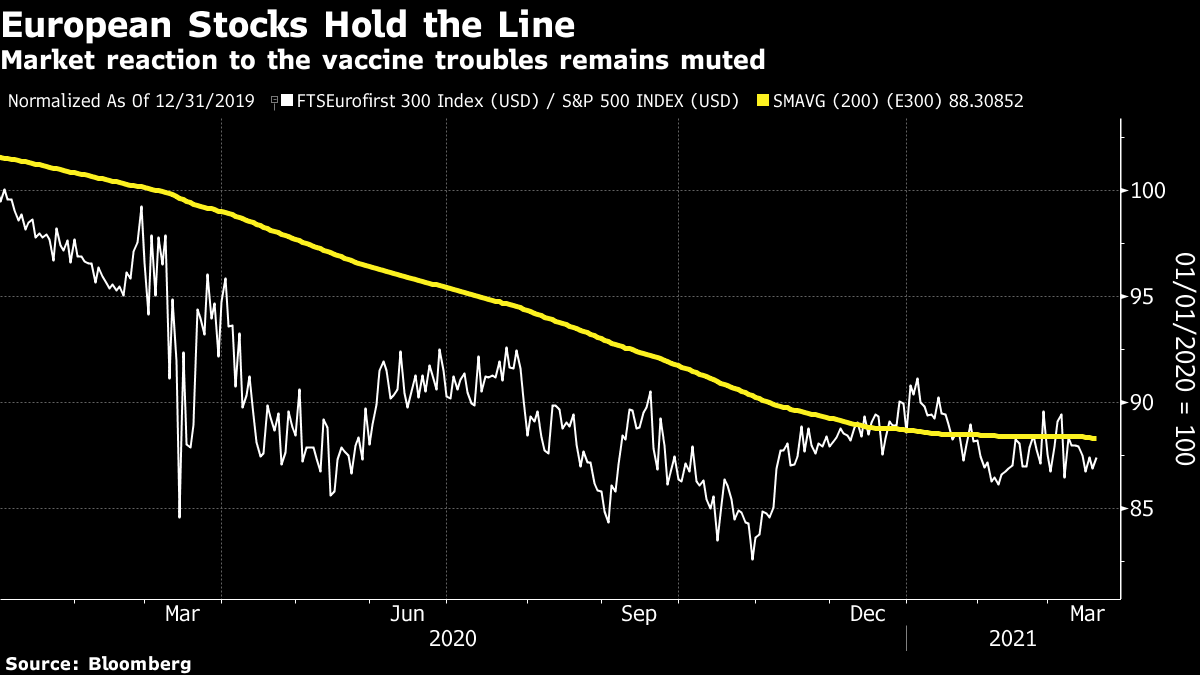

From Hope and Fear Set FreeAs the markets readied for Wednesday afternoon's announcements from the Federal Open Market Committee, there was apprehension in the air. Macroeconomic data over the last few days have been disappointing, such that the Citi US Economic Surprise Index, which measures how numbers compare to expectations, dropped to its lowest since June:  Despite this, the yield curve — the gap between 10- and two-year Treasury yields — widened above 150 basis points for the first time since 2015. Generally, a steeper curve implies expectations of reflation in the future, which will require higher rates. So this is a clear sign of economic optimism:  Meanwhile, the stock market was subdued in the morning. On the face of it, this was a set-up. The market was braced for the Fed to be unduly hawkish. That didn't happen. Jerome Powell and his colleagues provided all and sundry with reasons to buy stocks, but also validated the reflation optimism in the yield curve. Rather than step back from the message that the Fed is happy to be "behind the curve" for a while, and make sure to stamp out unemployment even if it means higher inflation, Powell reaffirmed it. This came first in the Fed's official statement. The first paragraph below is from the last statement, in January. The second is from March. Differences are highlighted:   So there is now a reference to an upturn, Covid-19 continues to be the Fed's greatest concern, and inflation "continues to run below 2 percent." There is no acknowledgement of the growing inflation fears of recent weeks. When it came to the Fed's official economic forecasts, revised from the last publication in December, they were spectacular:  The last calendar year in which GDP growth exceeded 6.5% was 1992. The Fed is also strikingly optimistic on its chances to reduce unemployment, and believes that inflation will already be comfortably above its 2% target by the end of this year. This sounds like great progress toward its dual mandates of controlling inflation and securing full employment. The downside to this for markets, of course, is that it also implies the Fed might need to raise rates sooner than expected. But if we looks at the infamous "dot plot," in which the projection of each member of the committee is represented by a dot on the chart, we find a narrow majority of the governors still expect to have rates at zero by the end of 2023:  This is a very direct message that the Fed really means it this time, and won't get scared by the next boomlet in inflation. Powell's last chance to get this message across came in his statement and Q&A with reporters, which is still taking place virtually. "We will continue to provide the economy the support that it needs for as long as it takes," he said. "It continues to depend significantly on the path of the virus." He emphasized that unemployment remained too high, had been unequal in its effects, and upended many lives. He also predicted that we are likely to see higher inflation over the next 12 months, but that it will be "transitory." As a result, it wouldn't meet the standard for the Fed to shift from its projected path on monetary policy. Translated, Powell was telling everyone that the Fed now cares more about unemployment than inflation, and that there's no need to worry that the likely inflation scare over the next few months as the great shutdown passes more than 12 months into the past will shake the FOMC into tightening monetary policy. For good measure, he also made clear that the Fed intends to avoid a repeat of the 2013 "taper tantrum" when bonds and currency markets had a shocked reaction to a changed message on its QE asset purchases. When the Fed thinks it needs to adjust, Powell said, "we'll say so, and we'll say so well in advance of any actual taper." Nothing to worry about guys; the economy is doing great, and you don't need to worry about any nasty surprises from the Fed. Unsurprisingly, the stock markets liked the message, led in particular by small caps. The leap at 2 p.m. in New York, when the Fed's statement came out, was palpable:  The dollar was less enamored. Rising in recent weeks on the back of higher yields and greater economic optimism, it sold off against the major currencies, and also against emerging markets (where a nasty exodus of funds in the last few weeks, as Treasury yields rose, had awakened fears of another full-blown tantrum):  For the longer term, it is hard to bet against a steeper yield curve. The Fed is going to keep rates at rock bottom for at least another two years, and is hoping for a more vibrant economy after that, so a widening between short- and longer-term yields seems almost inevitable. That in turn implies that banking stocks, directly benefited by a steeper curve, should continue to fare well. The same applies to the usual cohort of assets that benefits from reflation and a weak dollar: commodities, emerging markets, cyclical industries. The chance of a true "Inverse Volcker" in which the Fed reverses decades of deflationary psychology appears to be getting stronger. The risks? In the long run, we should be careful what we wish for. A little inflation might seem like a great idea now, but by the late 1970s people were sick of it. And in the short run, Powell is unquestionably right to remind us that the most serious risk is the coronavirus. Which brings me to… An Emerging European DisasterIf there is one risk that we could all see coming this year and that we were afraid of, it was the prospect of something going seriously wrong with the Covid vaccine rollout. That has now happened. Most nations of the European Union have now brought vaccinations using the AstraZeneca Plc vaccine to a halt, pending more research on whether it really does carry a risk of life-threatening blood clots. All vaccines have some risks, and there have been several well publicized deaths. The raw statistics available so far suggest that fewer vaccinees have developed blood clots than would have been expected from a random sample. Nobody is saying that the vaccine actually protects against blood clots, but it does make the drastic response by authorities look like an overreaction. AstraZeneca has been plagued by bad publicity since it published garbled results from mass tests, and the most widely published efficacy data suggest that its vaccine isn't as effective as rivals from Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech SE, and from Moderna Inc. Trust in the vaccine across the population may now be fatally compromised. This isn't good, as the EU is particularly dependent on AstraZeneca's vaccine. Back in November, I ran this chart compiled by Deutsche Bank AG of the efforts different countries had made to pre-buy vaccines. Some of them are already being rolled out, while other names on the list are unfamiliar because they aren't yet available:  Pfizer (in pale blue) and Moderna (in red) were important for the U.S., which made fewer orders of the AstraZeneca vaccine. Indeed, the British drugmaker hasn't even applied yet for regulatory clearance in the U.S. But the EU is for now mostly reliant on AstraZeneca (as is the U.K., where the vaccine continues to be rolled out). Continental Europe can ill-afford to do without it. This grows even more uncomfortably apparent when we looks at the figures for cases in the EU. They have been rising for a month. Ethically, this makes the decision to stop the vaccinations look odd to say the least. Covid can kill and "long Covid" can debilitate, and these problems are on the rise. More avoidable human suffering appears to be in prospect. And for markets, continued lockdowns and interruptions to "business as usual" look inevitable. Whatever date you had penciled in for Europe to return to normal, you probably need to move it a few months later:  For countries like Greece and Spain that are particularly dependent on the tourist trade, another wave would be a disaster. Highly contentious "vaccine passports" are now on the EU agenda, in a bid to make it possible for these countries to welcome some tourists this summer. But this won't happen without a big political fight first. To gauge just what a mess the EU is in, here is exactly the same chart for the US:  If there was anything we were really worried about three months ago, it seems to me it was almost exactly what is happening now, in Europe; a disastrous halt to the vaccination program, just as another wave of Covid is taking shape. The situation can still be salvaged, and all of us should hope that it will be. In markets, European assets have been bombed out from years of poor performance and don't have too far to fall. Even so, the performance of European stocks relative to the S&P 500 has been surprisingly muted as the EU's public health trouble has taken shape:  The weaker dollar following the FOMC will help buoy European stocks relative to the S&P 500. But it doesn't look as though the market has yet woken to a very alarming situation. Survival TipsA sheriff's officer from Georgia committed a gaffe for the ages when he told reporters that a man who had just been arrested on suspicion of murdering eight people had done it because he'd had a "bad day." Being charitable, it was a poor choice of words. But it does give everyone an excuse to listen to Bad Day by REM, or Bad Day by Daniel Powter, or Hard Day by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, or Hard Day by George Michael or Grey Day by Madness (great video), or the highly ironic Perfect Day by Lou Reed (warning: the video is a great scene from the movie Trainspotting in which Ewan McGregor passes out after shooting up heroin — it's a great piece of cinema, but you might not be in the mood for it). If you don't have the stomach for that one, try this version of Perfect Day, made to advertise the BBC; Lou Reed is followed in close order by Bono, Skye from Morcheeba, David Bowie, Elton John, and the cast of thousands carries on from there. Here's wishing everyone a good day. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment