Politics and CovidThe shocking news that President Donald Trump has tested positive for coronavirus has added a new level of uncertainty to next month's election. This is the latest and the most serious in a series of October surprises. Everyone should wish him the best. Before the news, I had written a note on what now seems to be the inconsequential topic of how the betting markets were treating the election: If you thought that Trump would probably be re-elected, it looked like the time to bet on him had arrived. There are more immediate questions. They involve checking on the health of the vice president, and of Joe Biden, who shared a platform with the president Tuesday night. Then there is an array of political possibilities. When Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson had a brush with death at the hands of Covid-19 earlier in the year, there was a wave of sympathy for him from across the country, which has since abated. Will there be such a reaction in the U.S.? And how will the president withstand the illness? Johnson relinquished day-to-day-power for a while; is it conceivable that such a thing would happen in the month before a U.S. election? Some other thoughts that arise: - This is almost certainly negative news for the economy, because the chances of a significant relaxation in lockdown provisions in the U.S. have just been sharply reduced. It was much easier to argue for reopening the economy when a large part of the population truly believed that the pandemic was a hoax. That will change, and many individuals' behavior will probably change even without a change in the official rules.

- The chances for a fiscal stimulus deal may well just have increased. Politicians on both sides will want to be seen to be achieving something in these difficult times, and Covid-19 suddenly looks like much more of an immediate problem than it did a few hours ago. A weak unemployment number might also help this.

- The chance of some deliberate geopolitical "surprise" to change the subject from Covid-19 may also just have risen. If this news turns out to work against the president, and his polling numbers deteriorate, then the possibility of some escalation in the dispute with China, an issue on which Trump has broad support, becomes that much greater.

- For stock markets, we can assume that volatility will rise and that defensive stocks (these days meaning the FANGs) will outperform.

- Perhaps the most interesting market to watch is the dollar. In the past, it has acted as a haven during times of alarm, even if the alarm emanates from the U.S. itself. That happened most famously when investors responded to the Standard & Poor's downgrade of U.S. Treasuries by buying Treasuries and the dollar. Is it still perceived as that kind of a haven? (More on this below.)

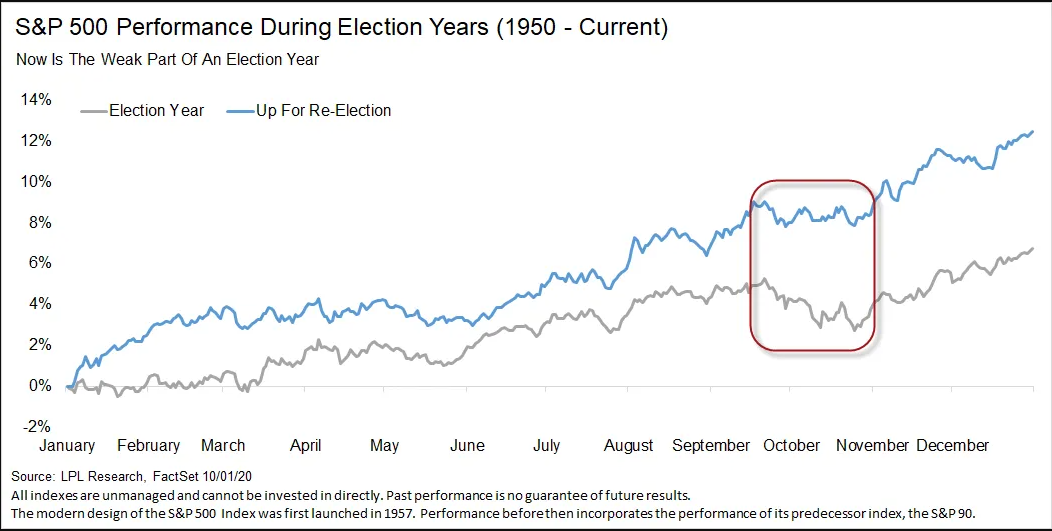

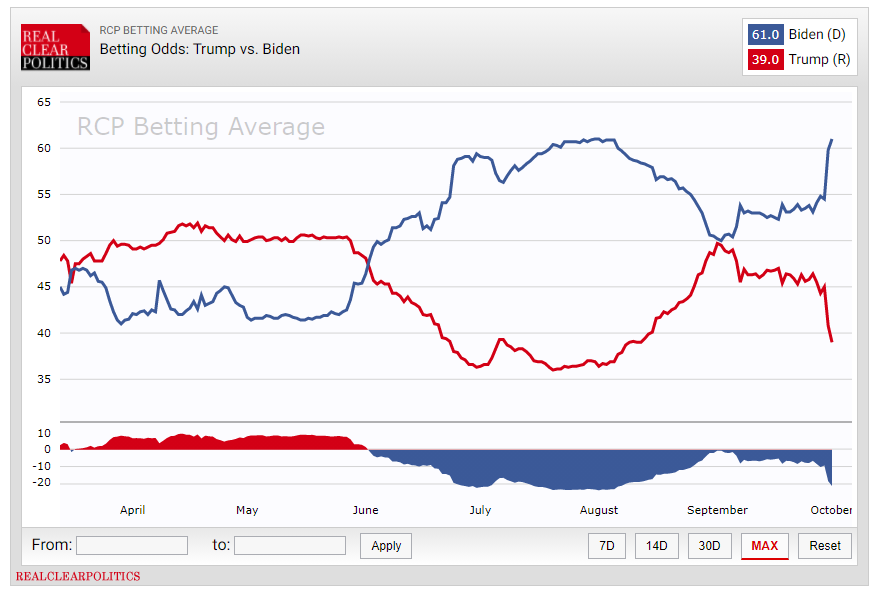

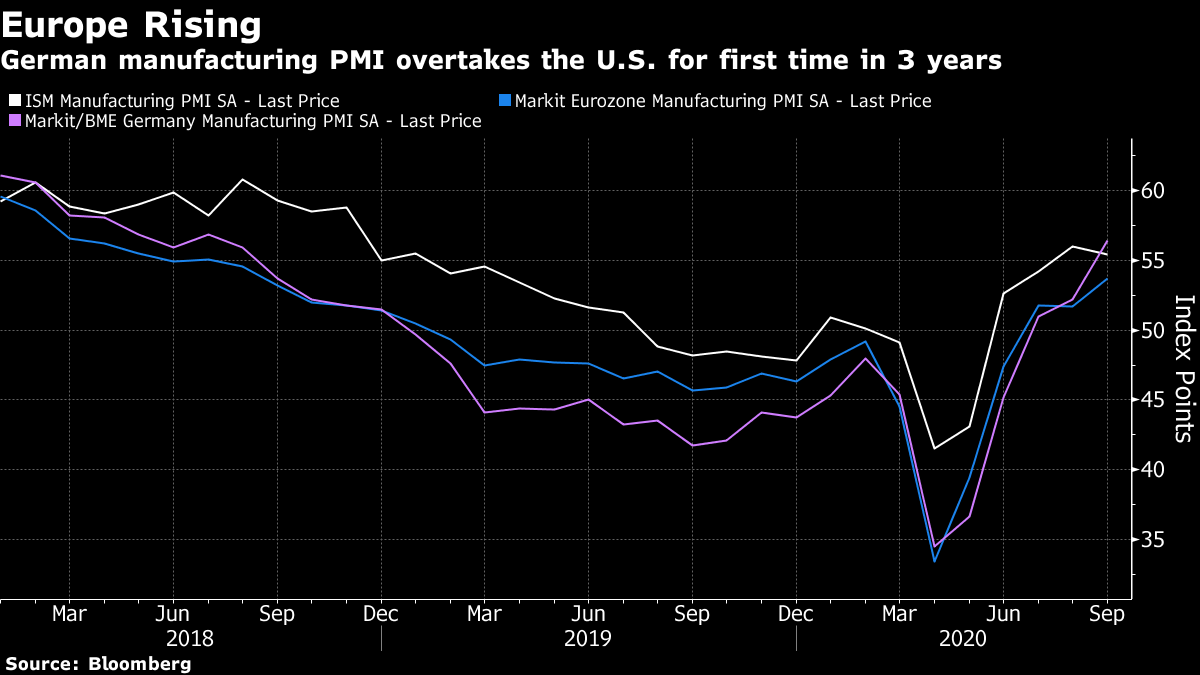

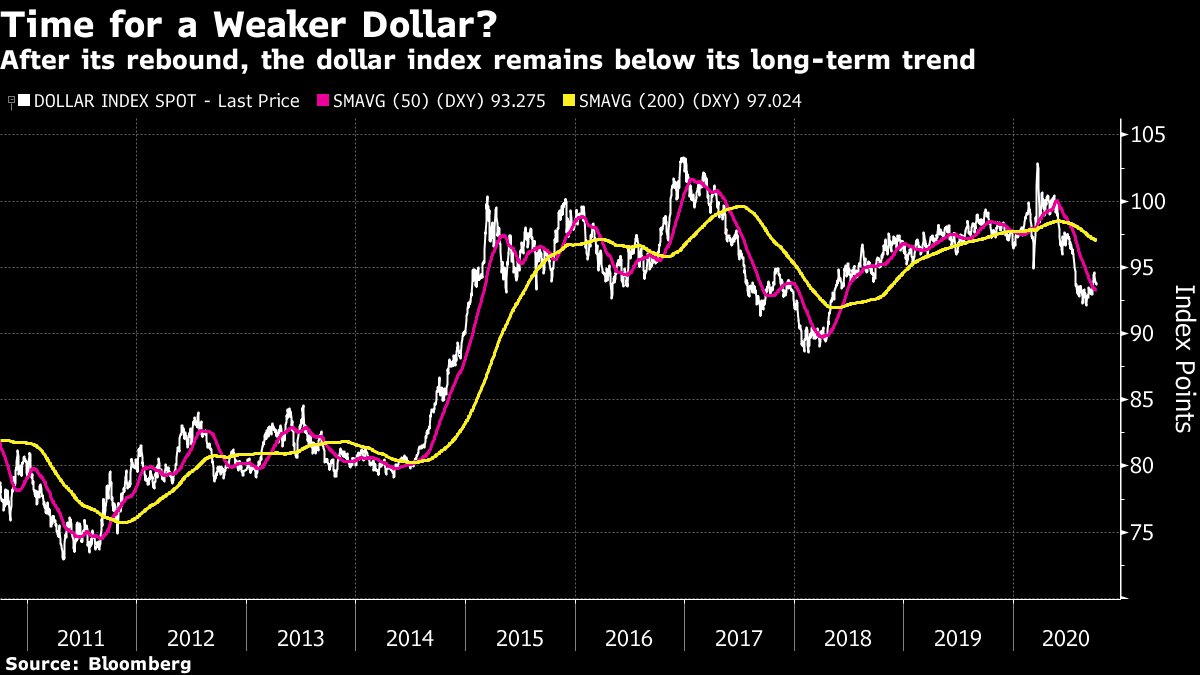

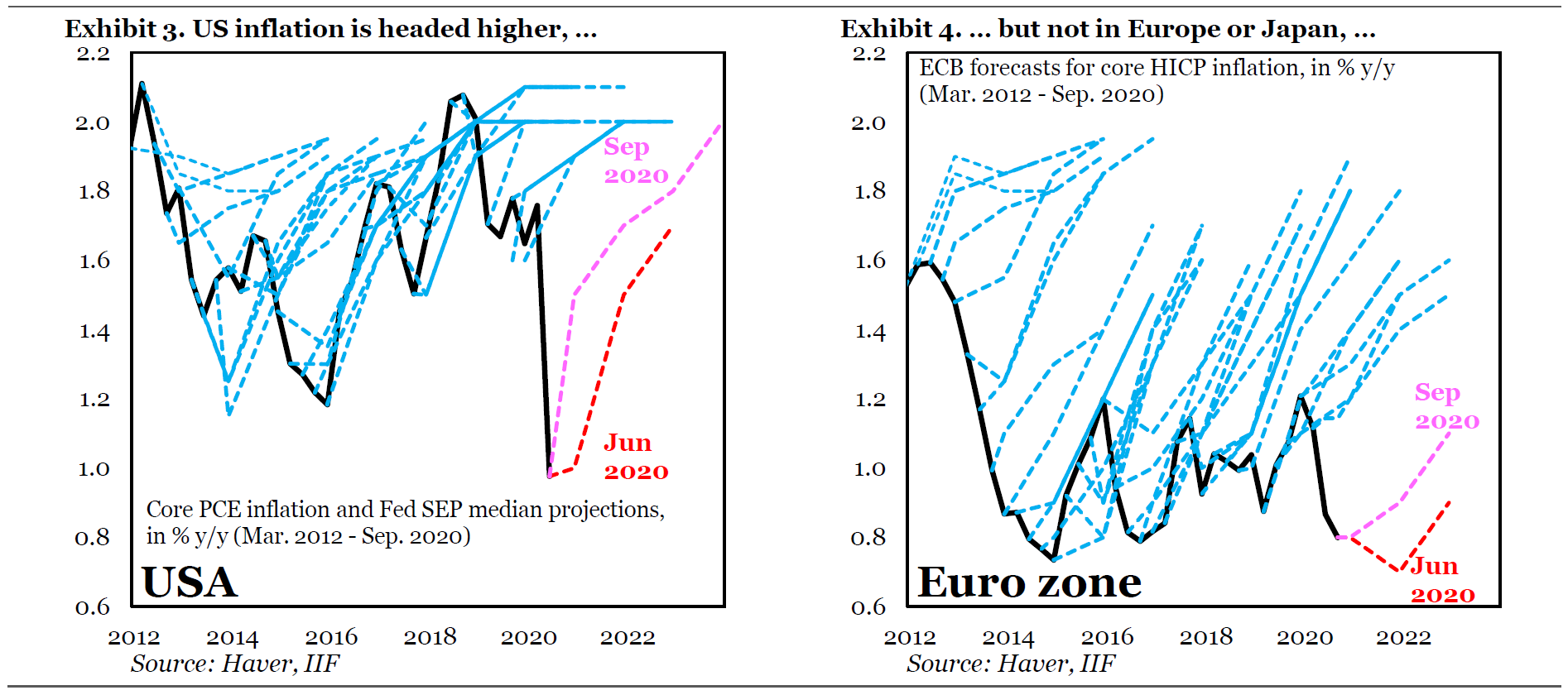

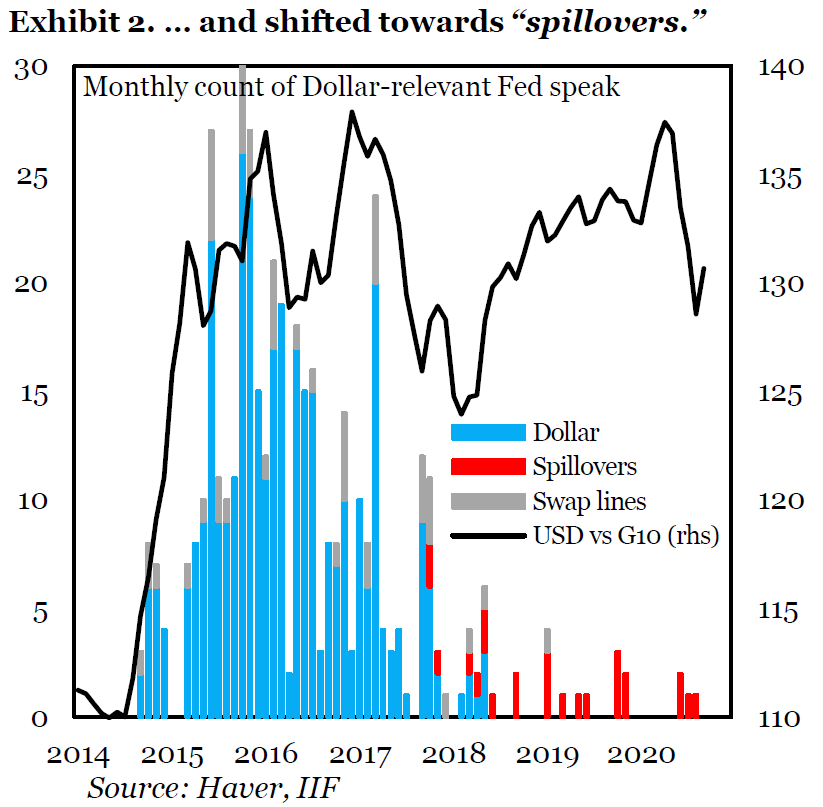

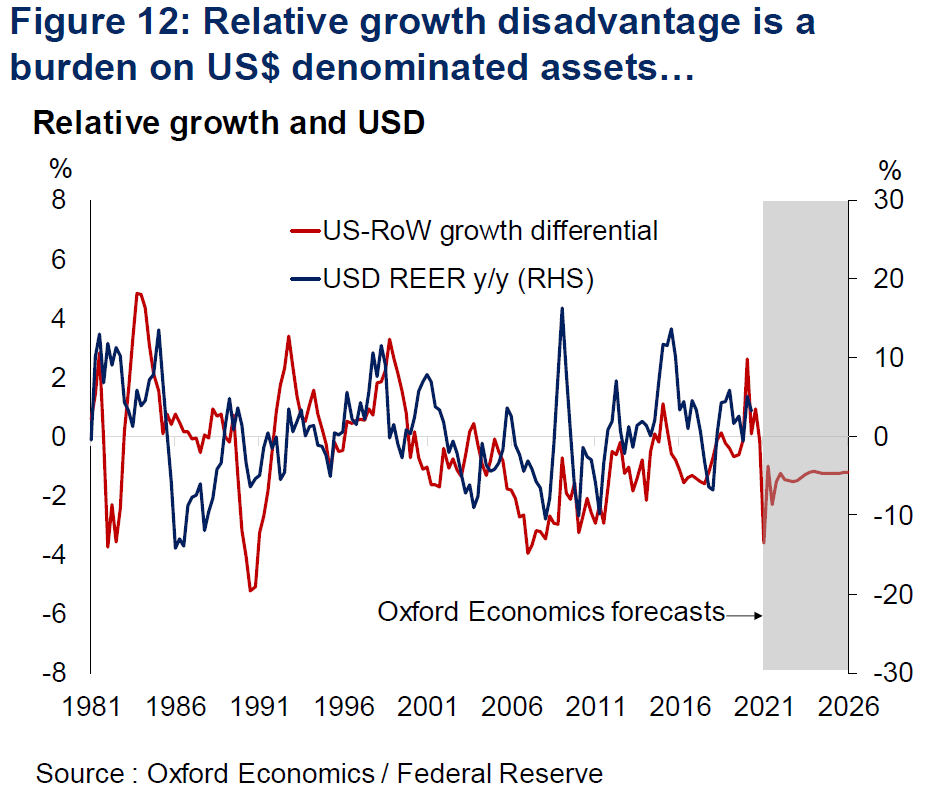

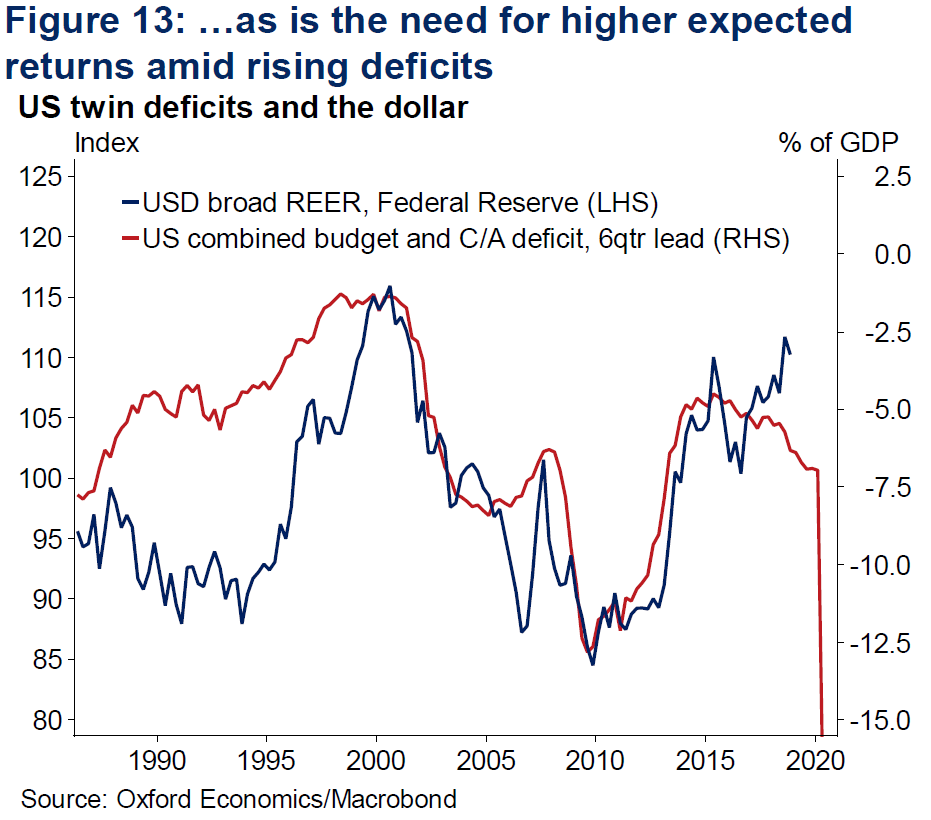

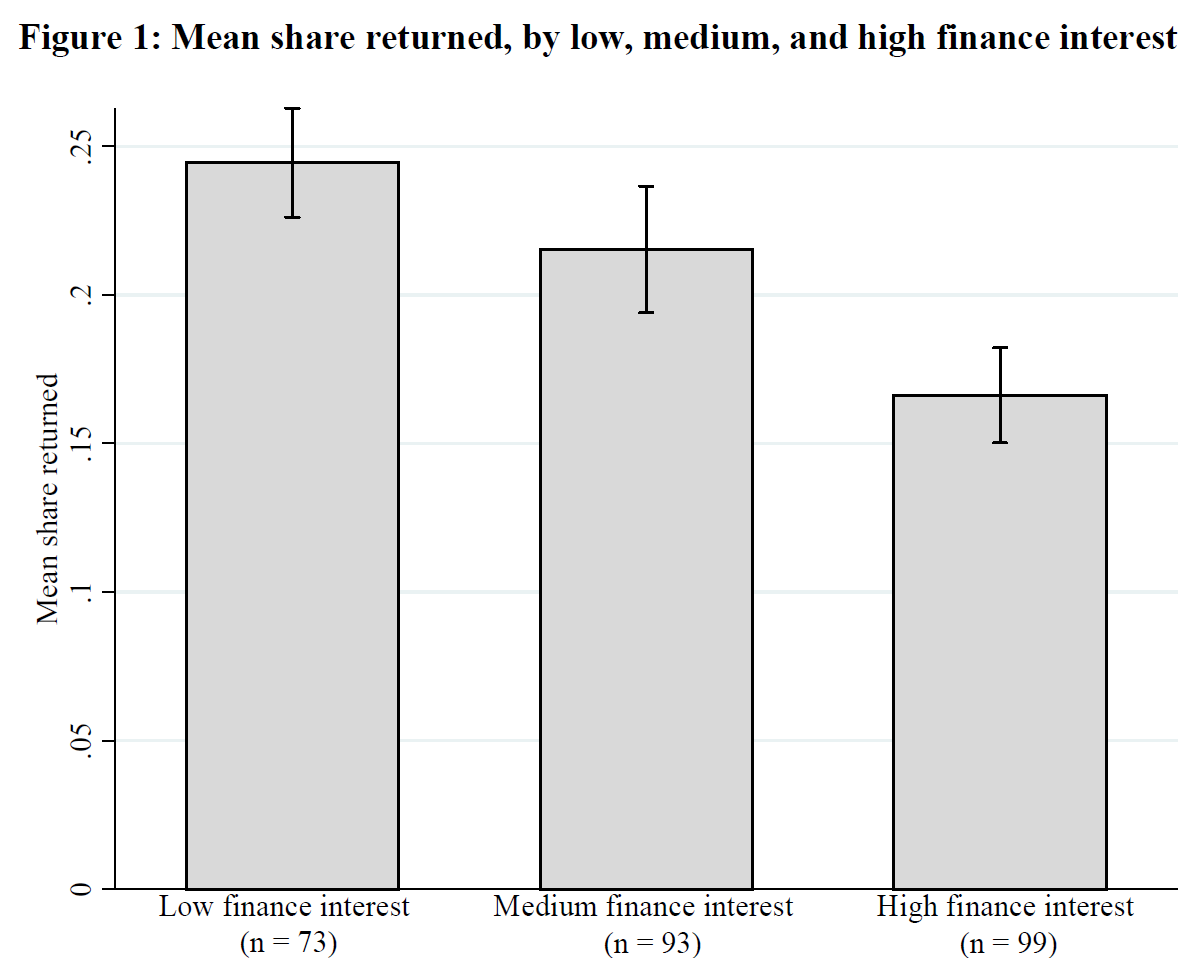

Before this development, polls following Tuesday's presidential debate, plus those suggesting that the Democrats now look likely to take the Iowa Senate seat that currently belongs to Republican Joni Ernst, pointed to a sharp improvement in their chances of winning both the White House and the Senate. That caused a sharp reaction in political prediction and betting markets. Intriguingly, the polls hadn't yet scared the stock market, even though we are entering the month when election jitters tend to weigh. The following chart comes from Ryan Detrick, chief market strategist at LPL Financial LLC:  Terrible though the news of the president's infection may be, the unemployment report, which comes out an hour before the market opens, may have greater impact. Meanwhile, even if the stock markets have been calm, the betting markets have not. According to RealClearPolitics, this is how they viewed the race before the latest news (which caused Betfair to suspend its presidential market):  Personally, I think those odds were sensible enough. Joe Biden plainly has his nose ahead. But as I wrote before the revelation about the president's health, the probability that Trump's chances will be perceived to improve from here at some point between now and election day is very high. That is even more true now. When last I checked, you could bet on a Trump victory for as little as 34 cents on the dollar in some places. If I were allowed to play these markets (which I'm not), I'd find those odds attractive. Dollar AlmightyAs we await the last U.S. unemployment numbers before the election, we have had a minor watershed in the ISM manufacturing numbers. Nowhere near as politically important, but widely followed on the markets, the latest monthly survey of supply managers logged a slight decrease in the strength of the U.S. manufacturing sector compared to a month earlier. For the first time in three years, German manufacturing's figure was slightly higher:  At this point, Europe's slower recovery from a deeper dip, largely driven by a more complete and rigorous Covid lockdown back in the spring, has turned into one that matches the U.S. The worrying second waves of the virus across the continent haven't yet knocked this off course. This leads to the question of the dollar. It has been popular for a while to predict the beginning of a prolonged downdraft. The Federal Reserve's efforts have left the U.S. looking like an international outlier. Rock-bottom U.S. rates for longer combined with a recovering Europe make a persuasive case for a weaker dollar. If the virus does recede from here, that will also tend to cause a depreciating dollar, as it will rob the U.S. of the haven flows that it receives at times of low risk appetite. The dollar has enjoyed a bounce in the last week, but it is now retracing and remains below its 200-day moving average. It tends to move in long cycles, so there remains a chance that a bear market could be beginning:  Now for another question. Is this good news? A weaker dollar relieves pressure on emerging markets, whose currencies have been far shakier against the dollar than the main G-10 currencies. It also helps to make American exports more competitive, and boosts U.S. stocks by raising the dollar value of their overseas earnings — all things that the current leadership in Washington wants. But there is also a worry that a weaker dollar could further imbalance an already unbalanced world. As these charts from the Institute for International Finance show, there is now a clear expectation for stronger inflation in the U.S. (from a very low base), but not in Western Europe or Japan:  Dollar weakness would tend to raise U.S. inflation by increasing import prices, while continuing the deflationary problems of countries exporting to America — which isn't what many want. As such, the IIF shows that Fedspeak has moved away from expressing any great opinion about the currency. Five years ago, after the dollar appreciated sharply in the wake of the oil price crash, the Fed found ways to make clear that it wasn't happy with a strong dollar. There doesn't seem to be any similar effort under way at present. Instead, Fed commentary on currencies is limited to the risks of spillovers from crises elsewhere.  Meanwhile, Oxford Economics suggests that the U.S. real effective exchange rate tends to move with its economic growth rate compared to the rest of the world. If some European catch-up is under way (still a big if), that again implies a weaker dollar. This is an illustration of Oxford Economics' forecast:  Then there is the issue of the U.S. deficit. Generally, the deeper the deficit and the greater the need for Uncle Sam to borrow, then the cheaper will be the dollar to entice potential lenders. If that logic works out this time, as this chart shows rather dramatically, then the dollar has further to fall:  We hear less about the phrase "global imbalances" these days. And a weaker dollar would also be a symptom of other factors that many desperately hope to see happen, such as a cyclical upswing involving a new commodity bull market. But if a dollar bear market does take further shape, bear in mind that it could deepen the inflation imbalances between the U.S. and the rest of the world. A Question of TrustThere is a widespread belief in the public at large that the people who work in finance are untrustworthy. That must rankle for the many trustworthy readers of this newsletter who work in finance, and as a worker in what is now known as the Fake News Mainstream Media, I sympathize. Trust is breaking down throughout society, and it is corrosive. However, if a new and fascinating piece of long-term research from a group of German academics is right, it does appear that finance is in part responsible for its bad reputation. Financial careers disproportionately attract students who are untrustworthy and, when it comes to applying for a job, financial firms do a great job of selecting the applicants who were most unreliable in their behavior at university. These are the findings of Trustworthiness in the Financial Industry by Andrej Gill, Matthias Heinz, Heiner Schumacher and Matthias Sutter. It's a big survey that is worth reading, resulting from ongoing research reminiscent of the Seven Up documentaries. Seven years ago, they arranged for students at the Goethe University Frankfurt to play experimental games, with small amounts of money at stake. It was a classic measure of cooperation, where players had a choice between maximizing the total pie for everyone, or sharing less and giving themselves a chance of a greater payout. A well as playing the game, they were asked a battery of questions about their interests and career intentions. The researchers also screened for gender (women were half the sample), and intellectual ability. It found a strong correlation between untrustworthiness and desire to work in financial services; those most inclined to do the dirty on their partners were also the ones most inclined to pursue a career in finance. In this chart, the less students shared, the more they were attempting to do their partners out of money:  So, finance students at the main university in Germany's financial capital turned out to have an unhealthy interest in maximizing money for themselves. The researchers returned to those students, now that most of them are established in the world of work. They discovered that those who had been most untrustworthy and held on to the most money for themselves in the sharing game had gone on to be the most likely to establish themselves in a financial job. There are lots of numbers and regressions in the paper — and it would have made for a fantastic TV documentary or reality show if the academics had turned up with cameras. Here is the summary of their findings: individuals who, at the start of their studies, express a strong interest to work in the financial industry are substantially less trustworthy than individuals with other professional goals. Importantly, this relationship persists if we consider actual job market placements. Individuals who find their first job after graduation in the financial industry are significantly less trustworthy than individuals who commence their career in other industries. The former group returned on average one third less than the latter group in our experimental trust game. Thus, the financial industry does not seem to screen out less trustworthy individuals. If anything the opposite seems to be the case: Even among students who are highly motivated to work in finance after graduation, those who actually start their career in finance are significantly less trustworthy than those who work elsewhere. Similar to our main results on trustworthiness, we have also reported a negative relationship between willingness to cooperate (in a public goods game) and students' interest in working in the financial industry.

They also conducted something of a control experiment, with students at universities in Cologne and Dusseldorf, places less likely to attract those most ambitious to work in finance. In an experiment testing how prepared students were to work in groups, those most keen to work in finance proved least willing to share. Finance offers the opportunity to make a lot of money, so it isn't surprising that it attracts those most prepared to cut corners. That part of the findings isn't that concerning. What is more alarming is that financial recruiters unerringly appointed the least trustworthy people to work for them. This was the academics' conclusion: Given that our results suggest that financial companies themselves do not screen out less trustworthy subjects, it is unlikely that the financial industry will address this issue itself by putting more weight (in the hiring process, not only in public statements) on prosocial preferences of future employees. This suggests that policy interventions might be needed to change incentive structures in the financial industry such that it attracts more trustworthy and prosocial candidates in the future.

This brings echoes of a debate that briefly flared in 2009 and 2010, but then seemed to fade as the financial crisis disappeared into the past. Should financiers treat themselves as fiduciaries with an ongoing relationship with their clients, or approach every relationship and deal as a transactional one? Old school financiers were shocked by the frankly transactional approach investment bankers had taken when selling their own clients lousy investments in subprime credit a decade ago; a younger generation didn't understand what the problem was. In Germany, at any rate, it looks as though the industry is recruiting more people who will treat their relationships as transactions. Survival TipsOK, more panic button music. I like the piano works of Claude Debussy immensely. In many ways they are impressionist paintings in musical form, invoking an image. They are also very lovely. Try this performance of Clair de Lune by the remarkable Georgian pianist Khatia Buniatishvili, or La Fille Aux Cheveux de Lin by the late Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli.

Have a great weekend. |

Post a Comment