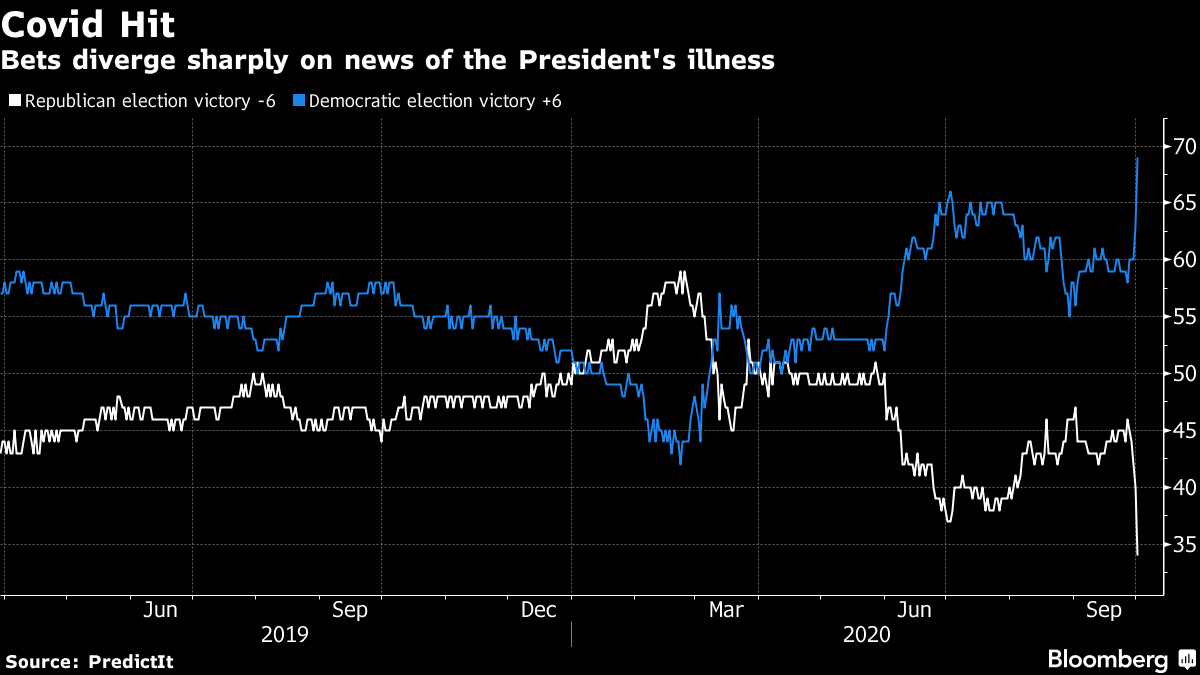

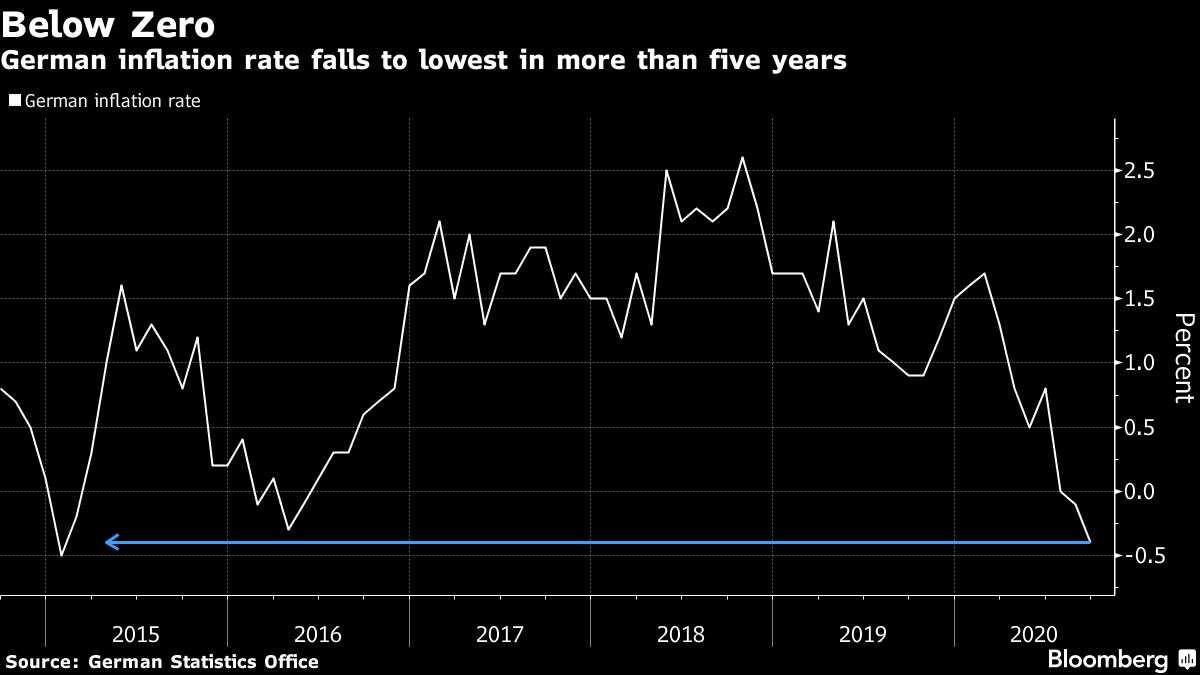

| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that wants you to wear a mask. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. This Changes Things President Donald Trump's announcement that he and First Lady Melania Trump had tested positive for Covid-19 is likely to dominate markets for a while. Risk assets, as expected, took a tumble when the news emerged, and money flowed to havens like the dollar, Japanese yen and Treasuries. Betting markets snapped, showing an initial sharp divergence in odds for a Republican versus Democratic victory in the Nov. 3 election.  Suffice to say, Wall Street will churn out a lot of research notes in the coming days. There was already an assumption that volatility will climb around the election, and the latest drama strengthens such arguments. Investors have been seeking protection for market swings in the event the election result is disputed. The added twist now is that volatility could also be sparked by the course of the virus on Capitol Hill. We'll have to wait and see if we're in the midst of a truly game-changing event. In the short term, uncertainty will spur demand for Treasuries since investors are likely to get even more nervous about risks around the election, says Viraj Patel, a strategist at Arkera Inc. But he added there's a limit to how much yields can fall in a "fleeting" risk-off environment. Rates experts talking earlier this week were already disagreeing about what happens to yields after the election. TD Securities reckoned the market was overestimating the prospects for a split Congress and policy gridlock, and that a Democratic sweep could drive long-end yields lower in a bull-flattening move on policy uncertainty. By contrast, Goldman Sachs' Praveen Korapaty sees a united House and Senate from a Democratic sweep driving the 10-year benchmark as much as 40 basis points higher on the prospect of heavier government spending. That boost could close the output gap quicker than currently anticipated, and that in turn could beckon the first rate hike in mid-2023, sooner than the market or the Fed expects.  Anatomy of a Crisis It may look calm now -- sedated, really -- but the U.S. government bond market is headed for more frequent bouts of stress. That's the conclusion regulators seem to be reaching at their sixth annual confab of the Treasury Market Conference this week. They weren't exactly short of conversation pieces this time around, as our Liz Capo McCormick reported. It may be the time-warping experience of living through the pandemic, but the market panic when economies started shutting down in March-April still feels pretty fresh. And the buysiders that dominated the opening panel -- including Vanguard's Sara Devereux -- had a few bones to pick about getting left high and dry by banks they rely on to help them move bonds. It's not new for money managers to gripe about dealers not stepping up with liquidity in times of market stress. Banks will prioritize among their clients when demand is heaviest. There's also widespread recognition that regulations since the global financial crisis have motivated them to economize on the balance sheet. But the "bottlenecks" buysiders reported experiencing in March had massive consequences, including a surge in yields that blew up a popular leveraged trade and forced the Fed to unleash unprecedented amounts of emergency funds to prevent a systemic event. Colin Teichholtz of hedge fund Element Capital Management said that without this intervention a "true fire sale" would've unfolded in the world's biggest bond market. And that's got regulators talking seriously about what needs to be done to address what's being seen as vulnerabilities in the $19 trillion Treasury market. Nellie Liang, former director of the Fed's financial stability division and now a Brookings Institution researcher, says there may be a need to expand the Fed's inner circle of 24 banks -- the primary dealers -- to boost market-making capacity. That proposal makes sense in light of the massive volume of government debt that primary dealers are required to shovel these days (they're obliged to bid at Treasury auctions). Their holdings keep setting new records as the market expands, and that growth isn't likely to abate much anytime soon.  Clear and Simple But expanding the primary dealer set comes with its own risks, despite heavy due diligence, as demonstrated by the ignoble departure of MF Global within months of entering the club in 2011. Better to disperse the risk of intermediation, says Stanford University's Darrell Duffie, who reckons buyers and sellers of Treasuries -- cash and repurchase market -- should transact through a clearinghouse, as they do in the futures, derivatives and equity markets. In a paper for Brookings, Duffie wrote that "without a broad central clearing mandate, the size of the Treasury market will outstrip the capacity of dealers to safely intermediate the market on their own balance sheets, raising doubts over the safe-haven status of U.S. Treasuries and concerns over the cost to taxpayers of financing growing federal deficits. "The weak functionality of the secondary market for U.S. Treasuries on Covid-19 crisis news was a wake-up call. Given the enormous volumes of trade in this market, which will rise markedly with the massive upcoming growth in U.S. federal debt, regulators of the U.S. Treasury market may now wish to conduct a study of the costs and benefits of introducing a broad central clearing mandate. This would improve financial stability, increase market transparency, and reduce the current heavy reliance of the market on the limited space available on dealer balance sheets for intermediating trade flows." Then there are the stopgap measures that regulators have already taken. The Fed announced this week the ban on buybacks and caps on dividend payments is extending into the fourth quarter, a move intended to keep banks amply cushioned with reserves into what could be a rockier year end. And earlier this year the Fed and other regulators agreed to exempt bank holdings of U.S. Treasuries and cash from calculations of their leverage ratios, to free up some balance sheet. That loosening of the rules is only supposed to last until March, but it's hard to find anyone in the banking industry at least who doesn't think it will be extended, or made permanent. "The SLR exemption for Treasuries and reserves is going to be hard to take away," Credit Suisse's Zoltan Pozsar said in an interview last month, "given the deficits and Covid situation and ongoing need for fiscal support." Which brings us to moral hazard, which isn't a popular topic right now. UBS's Seth Carpenter -- a former Treasury official and advisor to the Fed -- is among the few highlighting the enabling powers of the Fed backstop, and that steps should be taken to make further aggressive interventions less necessary. For his part, the New York Fed President John Williams said the amount of corporate bond purchases "is low enough that I don't think it's fundamentally changing market conditions really, in a first-order way." It's those second and subsequent orders that are so insidious, though. And as we contemplate certain echoes of the last crisis but one, with the return of slicing and dicing troubled commercial real estate debt .. well, what could possibly go wrong? The Great Deflate All is not well with inflation in Europe. It's back below zero -- in Germany too. That's troubling enough for the European Central Bank, without the nasty prospect of a fight over what exactly should be done. Governor Christine Lagarde has admired the Fed's average inflation targeting strategy, but some of her colleagues favor more tangible action.  Executive Board member Fabio Panetta floated the idea of yet another burst of stimulus, since "the risks of a policy overreaction are much smaller than the risks of policy being too slow or too shy." The shy faction has a solid membership, though, including his German and Luxembourgish colleagues. Increased stimulus would be a further sugar-rush for Italy's bond market, which has just turned its best quarter in a year and outperformed all its European neighbors. That's thanks in large part to the ECB's emergency purchase program, though signs of greater political stability, and of resilience against a second wave of the pandemic, have helped. Moreover, the interest rate on Italy's long-term borrowing is the lowest it's ever been. Meanwhile the minefield of pan-European fiscal spending has shifted from fears of profligacy among beneficiaries to fears of corruption. The debate is over potentially tying disbursements to rule-of-law standards, in light of the EU's concerns about the state of democracy in Poland and Hungary. Movers and Shakers (In this periodic section, The Weekly Fix spotlights personnel moves in the fixed-income world and its environs. If you have tips or suggestions, please write ebarrett25@bloomberg.net) BofA's chief sticks to his no-2020-layoffs vow as peers cut jobs Citi Names Fraser as First Female CEO of Wall Street bank Economist Claudia Sahm leaves Center of Equitable Growth Goldman shakes up units in new push to woo investors AIG's top black ranks get thinner with four leaders leaving RBC's Chandler, dean of Toronto's trading floors, to leave firm CIBC cuts portfolio managers, traders in 5% staff reduction Bonus Points CME notifies traders of virus case in Eurodollar options pit Wall Street preps systems for election night trading surge Hot-desking is a good way to lose your best staff |

Post a Comment