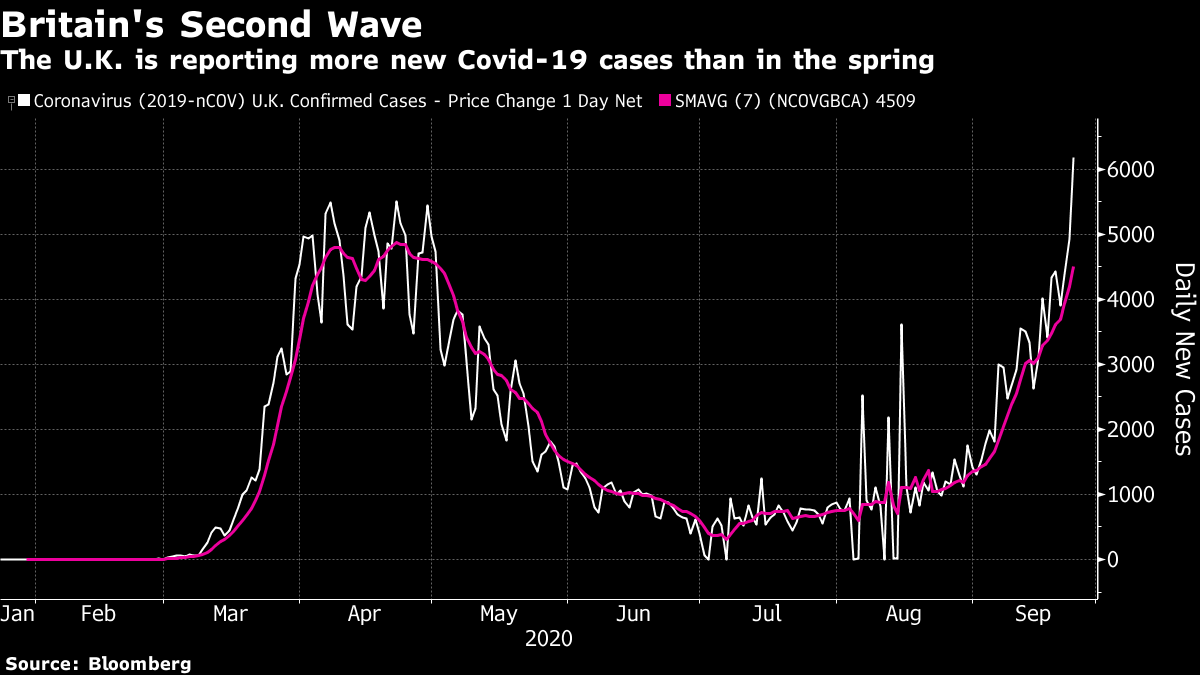

"All the Things We Can Think Of"The stock market sold off again Wednesday. It has done so more often than not this month. But it would be a mistake to draw a line between the latest bout of negativity and those that preceded it. Earlier sell-offs involved an attempt to correct obviously excessive prices in some of the dominant tech names. The latest sell-off was about rethinking the basic assumption that the U.S. and world economies can continue to recover, buoyed by continuing Fed largesse. This wasn't so much "we took things too far" as "we might have taken things in completely the wrong direction." It is difficult to get through one of these newsletters without mentioning the FANGs these days, so I'll try to make this the first and last reference. The NYSE Fang+ index barely underperformed the equal-weighted S&P 500 index Wednesday, and has gained more than 5% on the average stock over the last two weeks. This was true despite Tesla Inc.'s underwhelming "battery day" giving everyone an excuse to sell. At this point, the downdraft in U.S. stocks isn't about the FANGs. The tell as to what is worrying people came from the metals market. Gold has enjoyed a great bull run this year, up to and including record highs. That generally signals anxiety. Industrial metals recently completed a recovery that suggested newfound optimism for a cyclical upturn. Both precious and industrial metals have now changed course:  Why is gold falling? Put one way, the inverse relationship with real yields continues. When real yields rise then gold, which pays no income, can be expected to fall. This is true even if real yields are rising from deeply negative territory. To explain the intuition behind this, gold is widely regarded as a hedge against central banking irresponsibility. Recent speculation is that the Fed may not print money and cut rates with quite the gay abandon that had been assumed. This may or may not be good news for the U.S. economy, but it raises real yields and for investors in gold and in risk assets, who might benefit from currency debasement, it is definitely bad news. It is only a month since the Fed unveiled a historic change in its monetary policy strategy, suggesting that it will be prepared to tolerate far more inflation in future. It is only a week since Chairman Jerome Powell's press conference confirmed that the members of the Federal Open Market Committee collectively don't expect to raise rates for at least another three years. And yet real yields have been rising from their previous historic lows ever since that press conference. They have now gained 19 basis points from their low earlier this month, while gold has sold off sharply and has dropped below the $2,000 level that caused such excitement in August:  I argued last week that markets would soon realize it would have been greedy to expect the Fed to be any more dovish. That call isn't looking good, thus far. What has gone wrong? I think two main issues are involved. First, there is the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The passing of the liberal icon has no direct effect on markets, but the political conflict it has engendered does create much greater uncertainty over whether any kind of fiscal stimulus can be thrashed out any time soon. Now, members of Congress have to worry about re-election and a historically divisive court appointment. They may have neither the time nor the attention span to agree on a deal to tide people and businesses through the pandemic. Testifying to Congress this week, Powell tried to make clear that elected politicians needed to come through with more generous fiscal policy. In this, he was simply doing his job and prodding them into taking action he considered necessary. But when he said that some Fed emergency programs "require the support of the Treasury Department," that the Fed's credit facilities were no more than a "backstop" and that for many "a loan that could be difficult to repay might not be the answer," he rammed home to investors that even the Fed is not omnipotent and that "direct fiscal support may be needed." Another concern from the Powell testimony seems to have come from taking his remarks out of context. Asked about the Fed's Main Street lending program, whose take-up has been somewhat disappointing, he replied Tuesday that "I unfortunately think there's not much more we can do." On Wednesday, he said the Fed had "done basically all the things we can think of." In context, he was plainly referring to the specifics of stimulating lending to Main Street. But some heard the Fed chairman say he had already done "all the things we can think of" and took fright. This latest sell-off appears, then, to recognize that the horrible state of U.S. politics could get in the way of an economic recovery, while also acknowledging that the market remains dependent on extended central banking largesse. Corona ReturnsThere is one final issue at work in the sell-off: inevitably, it is the virus. The debate over whether second lockdowns would be necessary or even useful grows ever more intense. There are ever more persuasive arguments that the first lockdowns achieved little or nothing. But just as those arguing that the virus was in the process of burning itself out were gaining the upper hand, the official figures show a slight but distinct uptick in cases.  This proves nothing. The vital good news is that there is no similar uptick in deaths. But markets move on narratives, and the news flow of the last few days does interrupt a persuasive narrative that was taking shape, that in much of the U.S. the pandemic had reached the point where it had reached its "chokepoint" or burnt itself out. The people arguing that this will happen might well be proved right before much longer. But they will have to wait a little while, and those in the market who were already talking about the pandemic in the past tense need to take care. As my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Tyler Cowen argued, "some of the herd immunity theorists are on the precipice of being dogmatically wrong about matters of real import, just as were some of the most pessimistic mainstream predictions from March and April." Other news dented confidence. New York's Metropolitan Opera is canceling its entire 2020-2021 season, and there are reports of a pick-up in cases among the Ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities of Brooklyn, which already suffered a serious outbreak earlier in the year. The virus is yet to strike with a major outbreak in the same place twice, a telling item of evidence for those who argue that the virus reaches a chokepoint and then dies down. A second major outbreak in Brooklyn would, if it happened, be disquieting evidence against the "herd immunity" theory. And in the U.K., while deaths remain low, newly reported cases suddenly returned to the levels recorded when the pandemic first arrived. These figures are noisy, of course, but they made forhorrible headlines:  Then there was a dramatic confrontation between Anthony Fauci, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Senator Rand Paul, a strong libertarian, who argued that New York City might already have reached "community immunity," with about 22% of the population thought to have antibodies. Paul made a good summary of the case that lockdowns had been unnecessary. Then, in a much-watched exchange Fauci said: "If you believe 22% is herd immunity I believe you are alone in that." That gets to the crux of the debate. The next few weeks should bring us much closer to establishing which side is right. Finally, in Sweden — widely regarded as the test case for attempting to deal with the pandemic without lockdowns — there is news of a pickup in cases in Stockholm, and the possibility of new measures to tighten down on transmission. Markets have responded positively in recent weeks to growing evidence that the world could rid itself of the pandemic relatively painlessly. The last few days have brought data points that argue against that case — and markets are adjusting accordingly. Survival TipsToday it is time for some outsourced survival tips, thanks to some feedback. Yesterday, I recommended Chopin's piano preludes as good listening for a time when you felt the need to hit the panic button. (Such as now, probably.) I then received a recommendation for the complete preludes as played by Ivan Moravec; and it is indeed wonderful. Another kind reader drew my attention to this scene in Ingmar Bergman's Autumn Sonata, in which Ingrid Bergman teaches Liv Ullmann, playing her daughter, how to play a Chopin prelude. It's a remarkable piece of cinema, and it should make a great distraction from whatever you are doing. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment