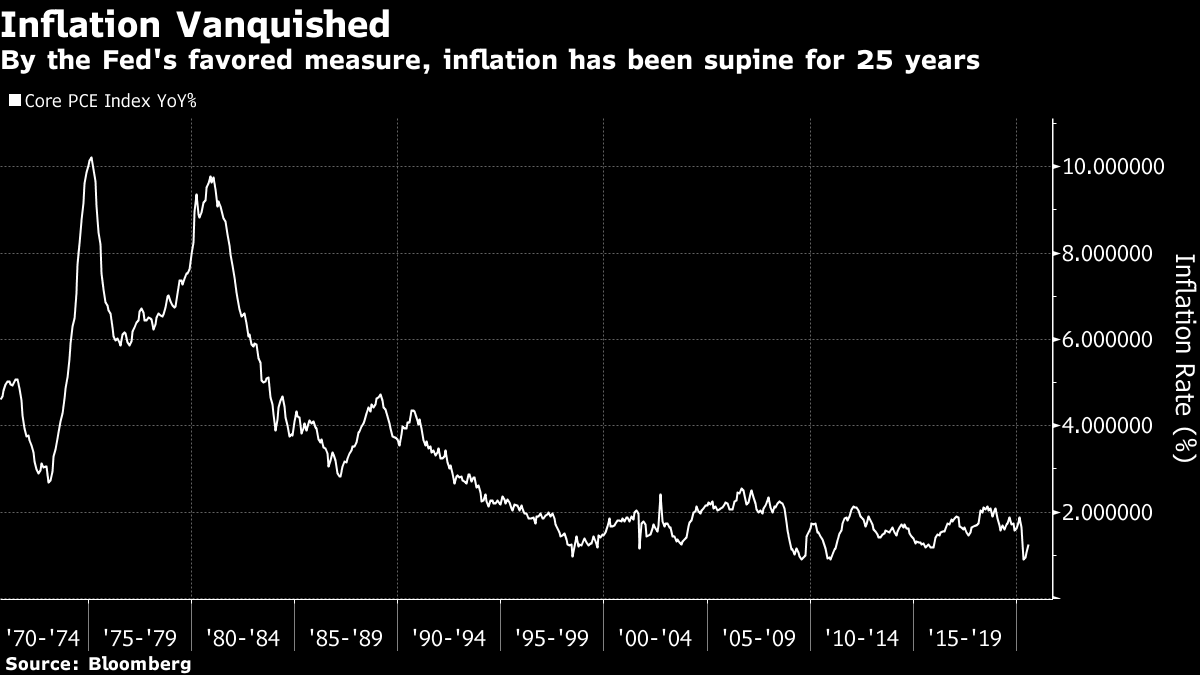

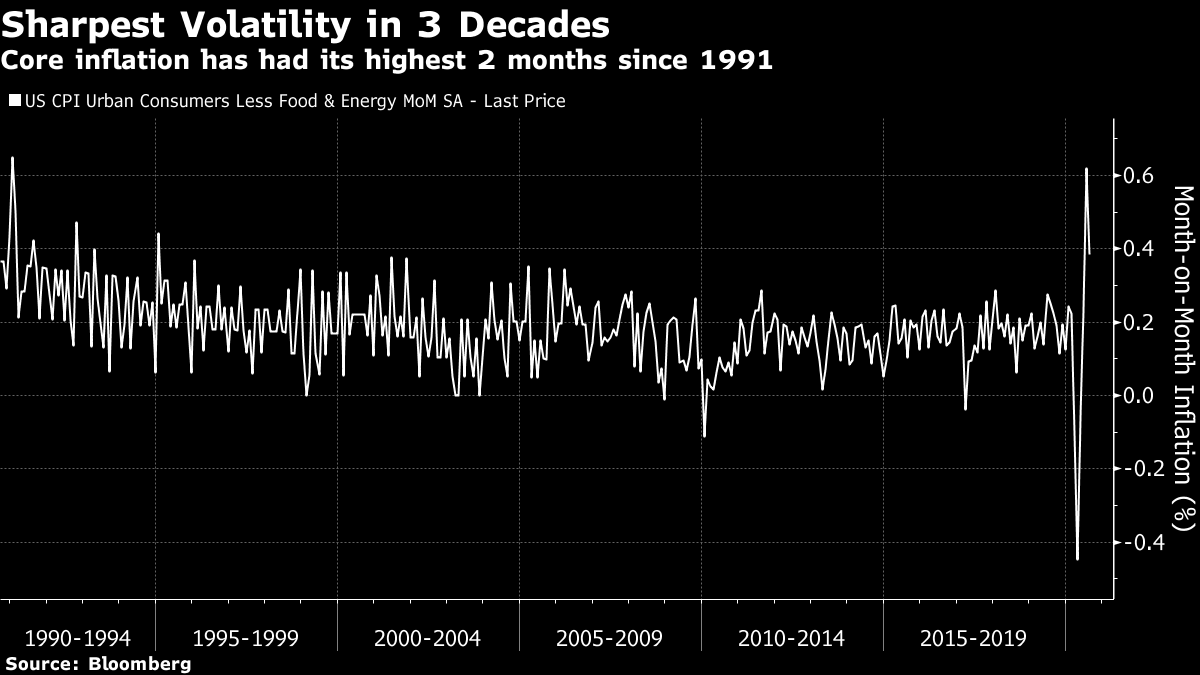

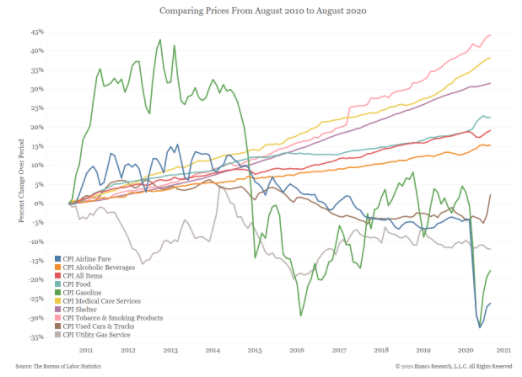

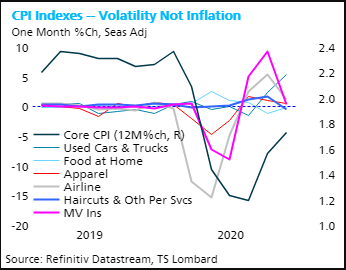

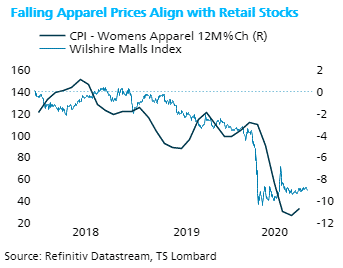

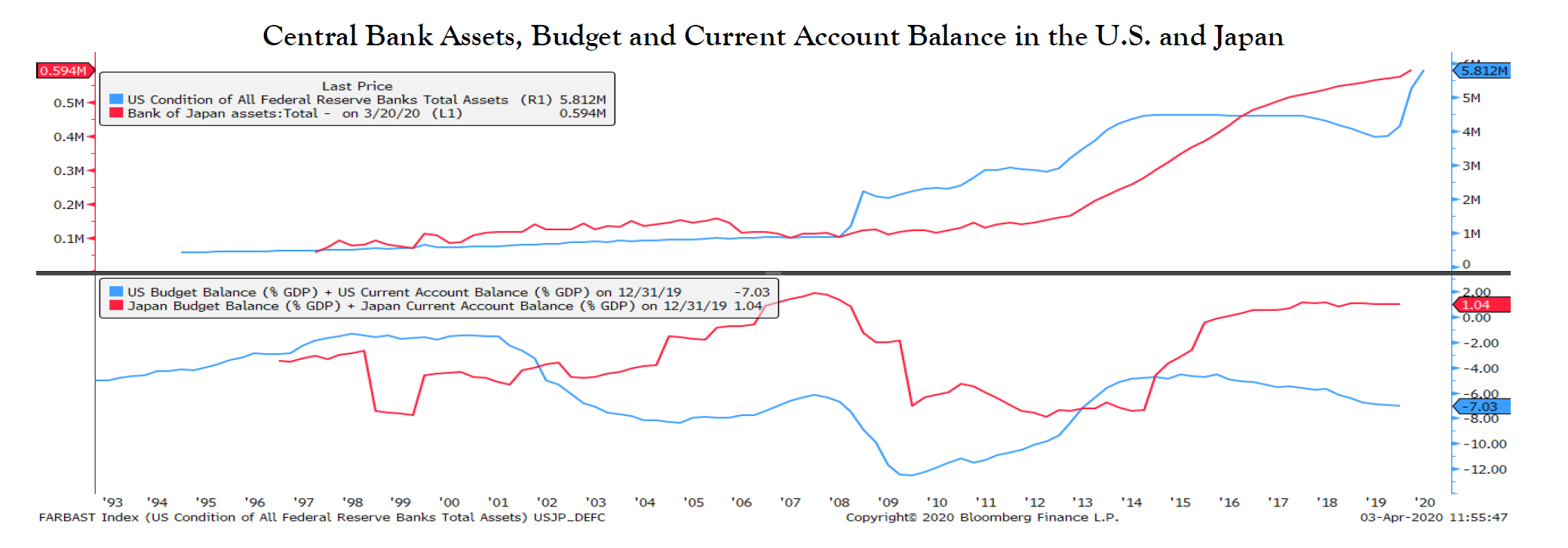

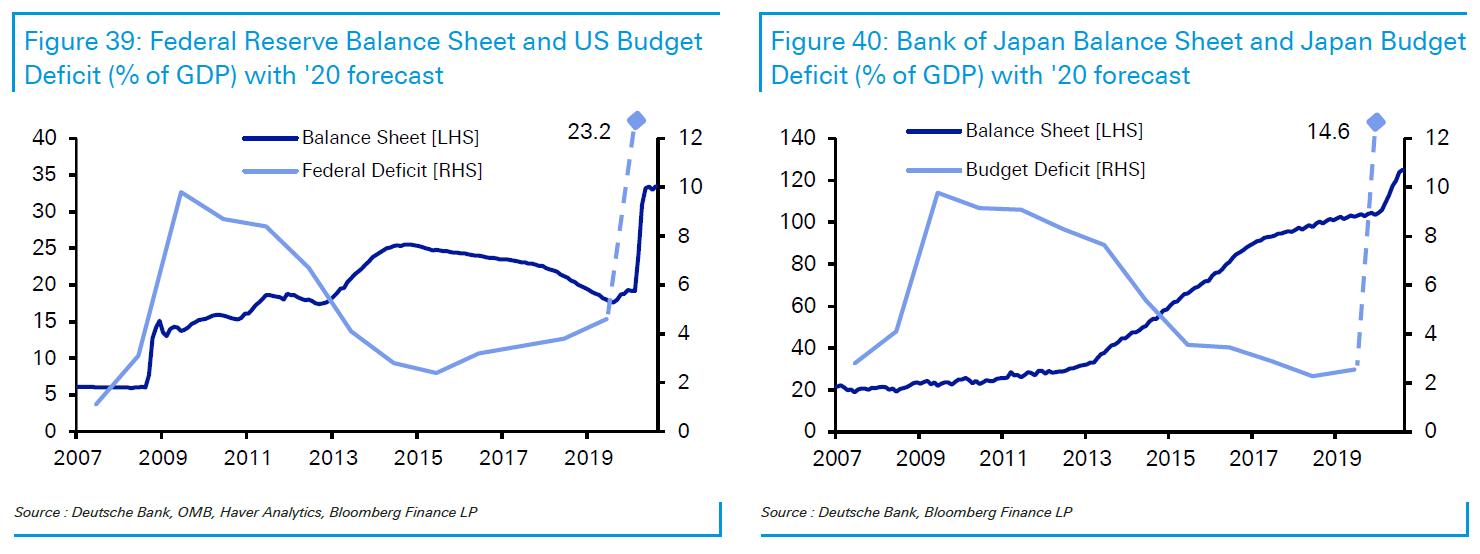

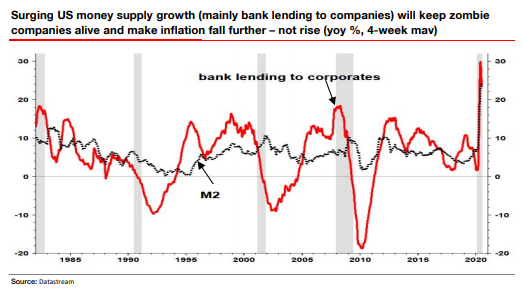

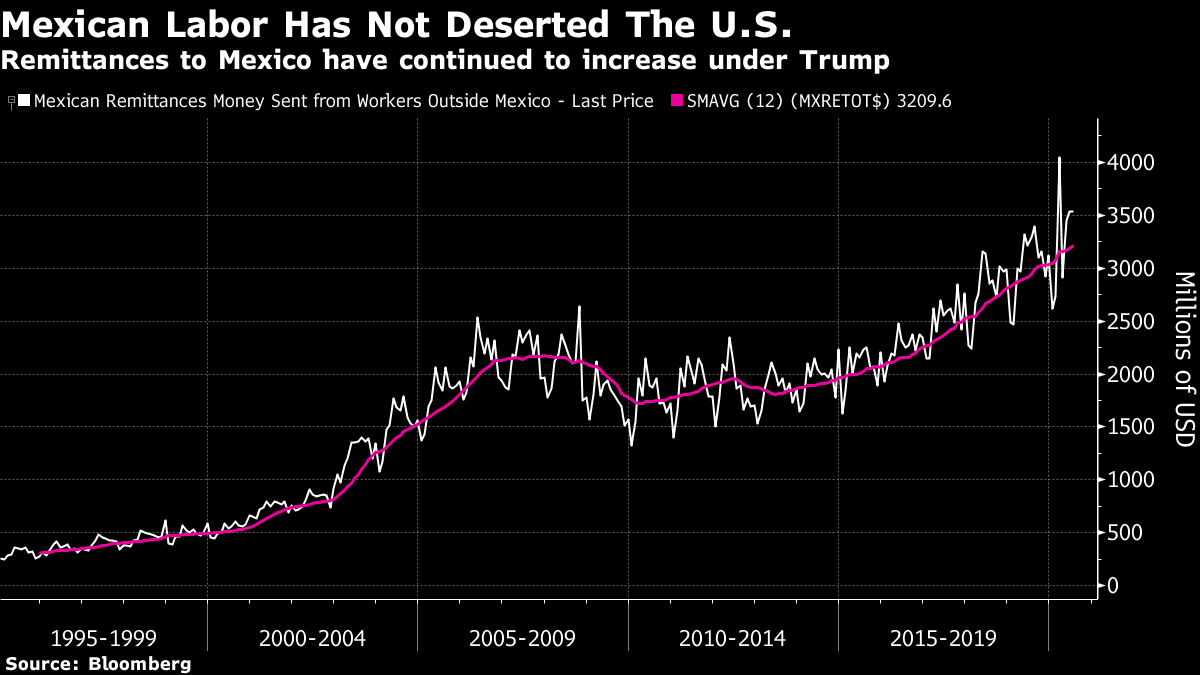

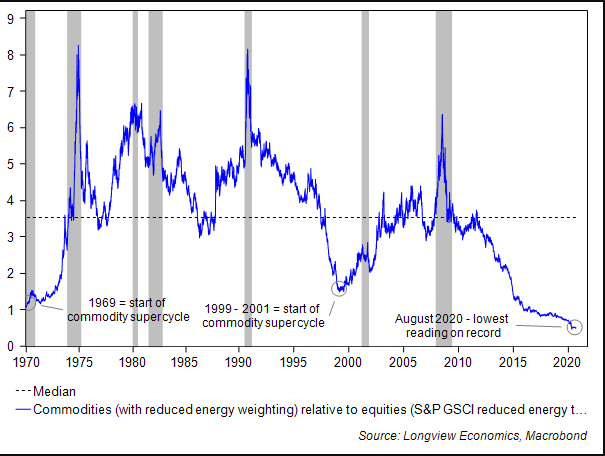

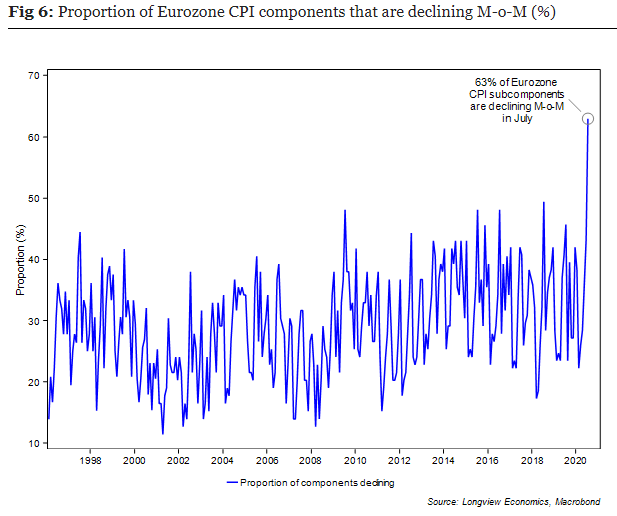

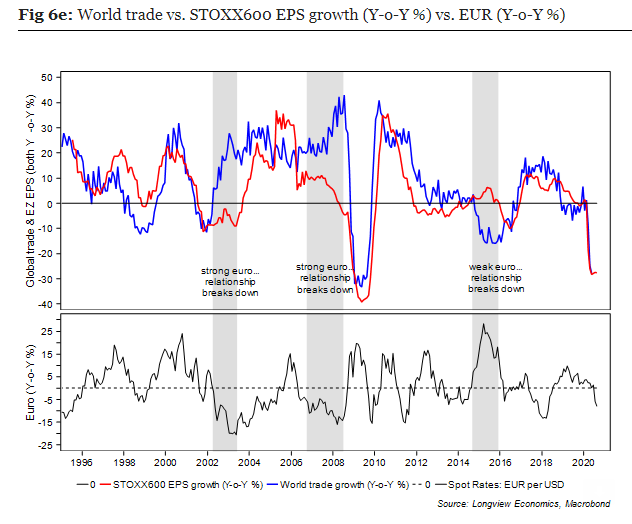

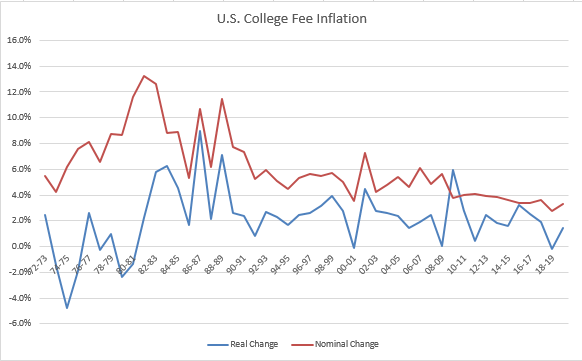

Demand-Pull, Cost-Push, and the Fed The Fed really wants to create some more inflation, and this week they are going to tell us a little more about how they intend to do it. But what are its chances, and where exactly is that inflation to be found? I will be taking part in a live discussion on the terminal Wednesday, in the quiet hours before the Federal Open Market Committee meeting, with Robin Brooks, chief economist of the Institute of International Finance, our Europe-based investment strategist Laura Cooper, and my cross-asset colleague Kriti Gupta. I hope you'll join in at TLIV when we'll try to get to the bottom of this. For now, I am going to frame the discussion. First of all, nobody thinks a return to significant inflation is imminent, and nobody doubts that product prices have been under control for a while. This is the Federal Reserve's preferred measure of inflation, the Core PCE Deflator, going back 50 years:  Expectations for the future, measured by break-evens in the bond market, have rebounded from their sharp fall at the beginning of the Covid crisis, so the market no longer believes the pandemic has delivered an emphatic deflationary shock. However, the picture is far from uniform. Britain is seen as having far higher ingrained inflation than the rest of the developed world. Meanwhile, Germany is perceived as still in danger of deflation.  The immediate aftermath of the crisis has also seen remarkable volatility in month-on-month core inflation. The last two months, as the economy rebounds, have seen the biggest rises since 1991, when the general level of inflation was much higher:  The economics textbooks approach this in different ways. Classically, inflation in goods can be divided into "cost-push," where costs rise (due to higher raw materials prices or supply bottlenecks, for example), and "demand-pull," where people have more money and bid up prices. Different factors can affect different items. To be clear, there are good reasons to fear more inflation in asset prices, and in the price of services (particularly in the U.S.) vital to maintain a middle-class standard of living, such as healthcare and college tuition costs. I am excluding these to keep this analysis manageable. In the following chart from fellow Bloomberg Opinion columnist Jim Bianco's firm Bianco Research, the main components of the U.S. consumer price index are mapped separately over the last decade. The greatest inflation has been in tobacco, followed by healthcare:  The following chart from Steve Blitz, chief U.S. economist of TS Lombard, zooms in on the last two years. There is plenty of volatility here, particularly in airline tickets — which were naturally affected by Covid-19. But this looks more like a shock than the start of a clear trend:  Blitz suggests that the trend remains deflationary. In the case of women's apparel, there was downward pressure in place before the pandemic, which subsequently accelerated. The impact on shares in malls, which were also already doing terribly, tends to suggest that a central deflationary trend remains firmly intact. The growth of online commerce has significantly reduced cost-push inflation:  So the effect of recent shocks has been plainly deflationary, once we strip out the volatility. Wherein, therefore, lies the case for inflation? It rests on monetary expansion. Yes, central banks also printed money to get us through the financial crisis of 2008, but that expansion wasn't as big as this one, and was accompanied by fiscal tightening. This time, we should brace for fiscal loosening. Michael Howell of Crossborder Capital Ltd. expresses this point of view clearly: It is a fact that all money that is anywhere must be somewhere! Hence, we expect these inflows to move through the markets and spread out into the wider economy over time, with gathering risks, in our view, that high street inflation will stir by mid-2021. Yet, the transmission process will be subtly different from 2008-09 for three key reasons: (1) much of the recent monetary growth is occurring in the narrower or 'retail' monetary aggregates, i.e. M1 and M2, which are linked more closely with real economy spending than the broader and wholesale measures that tend to be linked to financial asset purchases; (2) monetary injections are supporting fiscal spending measures, whereas in the wake of the GFC#1, fiscal policy shifted towards austerity, and (3) this crisis involves a supply disruption to the real economy, rather than a supply disruption to credit markets and funding as in GFC#1. Post-GFC#1, regulators forced many banks to increase their capital-to-asset ratios, which impaired lending. Today, policy-makers are partially relaxing these constraints. As such, this crisis stands to hit production, far more than spending. One of the first counter-arguments consists of one word: Japan. That country's central bank has been forlornly printing money for decades without sparking inflation. But there are important differences with the U.S. This chart from Vincent Deluard of Stonex Group Inc. compares the growth of central bank assets in Japan and the U.S., in the top frame, with the countries' budget deficits, in the lower. The U.S. is much more prepared to run a budget deficit than Japan. This doesn't prove that the U.S. will succeed in sparking inflation where Japan failed, but it is a major difference:  The following chart from Jim Reid of Deutsche Bank AG, which includes estimates for this year, shows the U.S. budget deficit is heading for 23.3% of GDP, compared to 14.6% for Japan:  This is a cogent and sensible case. What response is there? One of the most intriguing comes from Albert Edwards, chief investment strategist of Societe Generale SA, and for many years an infamous equity bear and bond bull. Despite the huge increase in the money supply, and despite acknowledging that a turning point is probably approaching, he is sticking with his bond bullishness for now. This is his reasoning: Personally, I believe this rapid money supply growth will actually worsen the current deflationary bust. Why? The flipside to looking at money supply growth is to look at its counter-parties on the asset side of the banks' balance sheets. It is clear that the main driver for the recent explosive 25% monetary growth has been bank lending to industrial and commercial companies, which despite only comprising a quarter of total bank lending has contributed some 70% of the total rise in lending over the past year, surging 30% yoy. One thing we now know for sure after Japan's lost decade: keeping zombie companies alive with "extend and pretend" bank loans creates deflation, not higher inflation. Zombie companies, for the uninitiated, are those that wouldn't be able to stay solvent without the phenomenally low interest rates that reduce the cost of refinancing their debt. The binge of leverage in the last six months will, in Edwards' view, lead to malinvestment, a further reduction in creative destruction, and for the time being even more deflation (through ever weaker "demand-pull"):  Against this there is the issue of "cost-push." The era of globalization appears to be coming to an end. If the U.S. is really about to decouple from China economically, there are plenty of possible positive effects. The obvious negative will be higher cost-push inflation. Another aspect of globalization is movement of labor. The U.S. government aims to reduce the amount of migrant labor. So far, this hasn't happened, judging by money flows. Remittances from migrant workers to Mexico have continued to increase:  Again, a reduction in the use of migrant labor by American companies might well have many positive consequences. But it would increase costs and tend to increase inflation. The Tale of Commodities If there is one other source of inflation, it is commodity prices. Prolonged weak demand tends to lead to supply destruction, which begets another cycle of rising prices. These affect cost-push inflation. Excluding energy, Bloomberg's commodities index has regained all the ground lost to Covid-19 and is on its sharpest upward trend in many years:  This ties in with the fascinating notion of the Kondratieff wave, named after a Marxist economist who was shot by Stalin. His work on commodity cycles continues to draw attention. These tend to be long, and the current downward one has been in place for almost a decade. That is on the short side for a Kondratieff wave, but if China really is back to buying as enthusiastically as it did in the 2000s, and if producers have cut back supply, it's possible that a new upward wave is starting. One other feature of Kondratieff waves, as pointed out by Chris Watling of Longview Economics in London, is that they tend to overlap with cycles in the stock market. Equity bull markets tend to happen during commodity bear markets (as in the 1990s and in the last decade) and vice versa. On that basis, we might be ready for a new Kondratieff wave, because commodities are as cheap relative to equities as they have been in half a century:  Meanwhile in Europe... Germany and the rest of the euro zone is perceived to have a particularly severe deflation problem. This chart, also from Watling of Longview, shows the extent of the difficulty. A higher proportion of inflation-basket components is declining than at any point since the birth of the euro:  The strengthening euro is an added challenge, reducing import prices and hence cost-push inflation. Former European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet, who developed code words to make his intentions clear to the market, would indicate a currency move had gone too far by calling it "brutal." The flurry of ECB-speak in the past week indicates current governors don't find the euro's strength brutal enough to try to argue down the currency. It may have an effect, though. The euro zone is more reliant on exports than the U.S. As the following chart shows, growth in its stock market tends to move in line with world trade, and a strong currency limits the benefits. The combination of currency strength and weak global trade wouldn't be at all good for euro-zone asset prices or the European economy. So a strong euro may not only limit cost-push inflation but also, less directly, demand-pull inflation as well.  Survival Tips Now let's return to the subject of college tuition inflation. As the devoted father of a U.S. high school senior, it is a subject close to my heart. I have no claim to be an expert, but college inflation is an extraordinary phenomenon. I created the chart below from data I downloaded from the College Board's website. It covers the average cost, including living expenses, of a private four-year college education, which is an increasingly important passport to a middle-class lifestyle. The red line is nominal fee inflation, and the blue line is real fee inflation (or nominal inflation minus the official CPI that year). With the partial exception of 2018-19, when real inflation was -0.2%, the cost of college has increased faster than the general cost of living every year for four decades:  This is breathtaking, and hard to explain or excuse. At present, with many universities unable to teach in person at all, and Covid interrupting the standardized tests on which many of them rely, the process of applying is even more of an ulcerating nightmare than usual. So might I suggest looking at international options? This is one form of globalization that could reduce U.S. inflation in a very positive way. To cite one example, the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, the first international college to become part of the U.S. common application system, charges $32,200 per year at current rates for its four-year courses. Similarly prestigious American universities charge roughly double that. I noticed when I gave a talk to the St Andrews economics society a few years ago that the room seemed to be full of Americans. Now I understand why. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment