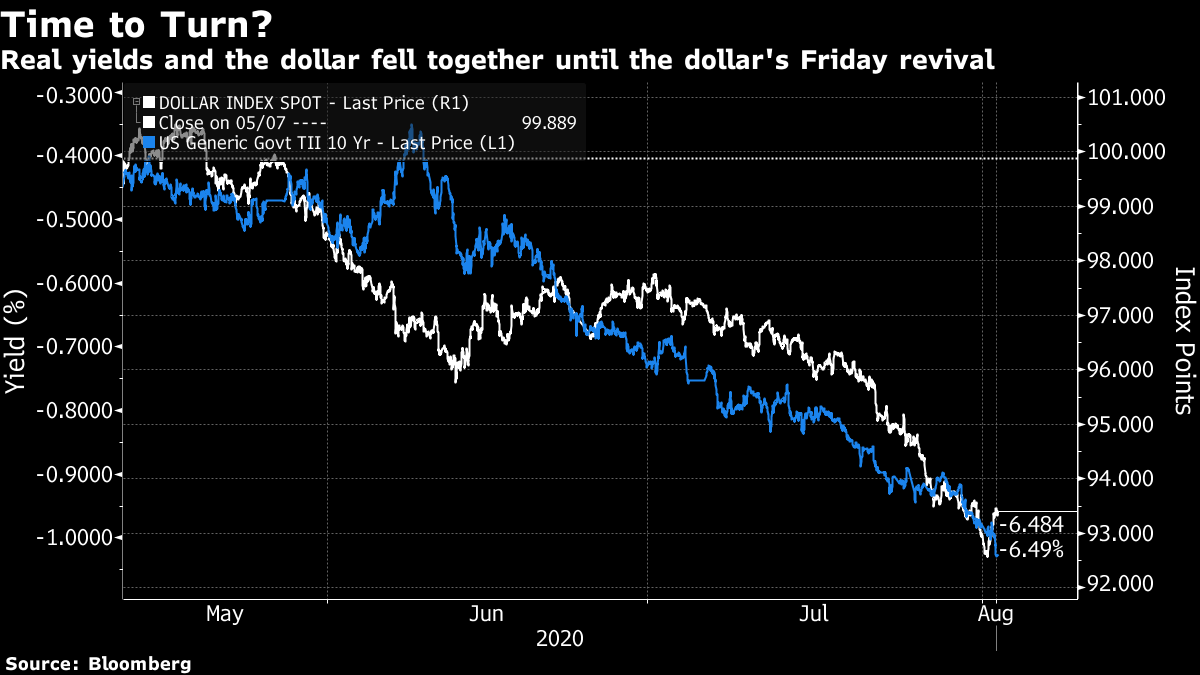

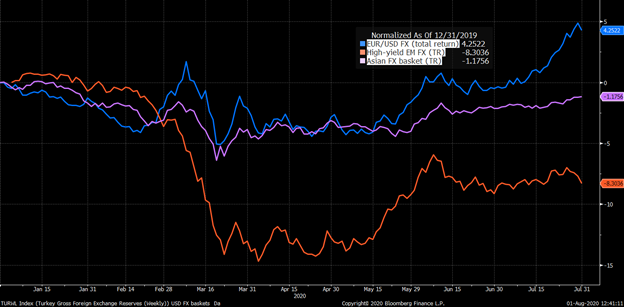

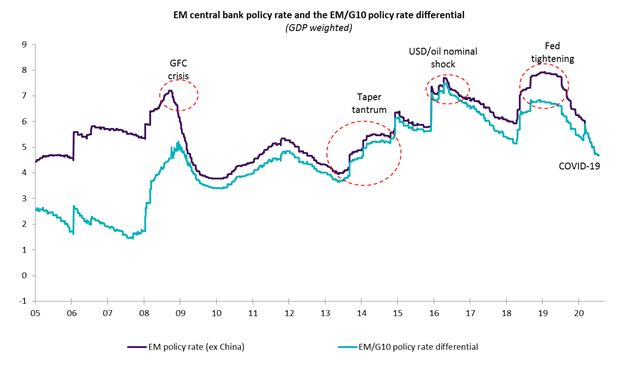

False Positive Is the decline of the dollar over? The U.S. currency has been falling steadily ever since the world exited the initial stage of the Covid-19 crisis. It has done so in line with the spectacular decline in real yields. This makes perfect sense. With lower yields, there is lower "carry" to be earned by parking in the dollar, so the currency would be expected to weaken. But last week ended with a distinct variation of the theme. The 10-year real yield dropped below minus 1% for the first time since inflation-protected Treasury bonds have been on issue. Meanwhile the popular dollar index, which compares the currency to a group of leading counterparts, suddenly enjoyed its strongest rally in months, gaining almost 1% into the close:  A weaker dollar is generally regarded as a desirable for a number of reasons. A strong dollar tends to mean that money has gone into the U.S. seeking a haven, so the slide of the last few months shows a return of risk appetite, even as the virus remains unbeaten. Also, a strong dollar causes problems for emerging markets. The depreciation of the last few months should have relieved pressure on a number that had taken on too much dollar-denominated debt. The only problem is that this hasn't in fact happened. The following chart, from NatWest Markets, shows that the dollar's weakness of June and July has been almost solely about the strength of other developed-market currencies, particularly the euro. Against Asian currencies it has held steady. And against "high-yield" emerging market currencies, it has actually strengthened. Those high-yield currencies enjoyed a recovery as the worst of the crisis appeared to pass in May — they have fallen over the past two months:  The weaker dollar may not, then, have been as positive a sign as was hoped. The main reason the high-yielding currencies remained weak was because their central banks had no choice but to cut rates in the face of the pandemic. That substantially reduced the advantages to holding money in those currencies. This NatWest Markets chart shows that despite the precipitous fall in U.S. real yields, emerging markets rates are at the narrowest spread over rates in the G-10 since the taper tantrum of 2013. Potential pressure on emerging markets remains considerable if the dollar begins to regain strength:  The greatest hope to avoid a classic emerging markets debt-and-devaluation crisis is that central banks' actions haven't spurred inflation, yet. Citibank's inflation surprise indexes suggest that investors were unprepared for the scale of the slowdown:  In the week ahead, which has the customary glut of macro data to accompany the beginning of the month, the central banks of Brazil and India will meet. Both are expected to continue easing, as they deal with what appear to be serious virus outbreaks. Those meetings, along with Tuesday's gathering of the Reserve Bank of Australia, another country that is grappling with a serious Covid resurgence, will be more closely watched than usual. What will drive the dollar from here? After such a prolonged downdraft, it looked oversold on plenty of measures, so we might well see it bounce back further aided by technical factors. But the virus, as ever, may have most to do with it. The critical flaw in the dollar over the last two months has been the deterioration in the public health situation in the U.S., while other countries continued to have the virus under some kind of control. As Marc Chandler, foreign exchange strategist at Bannockburn Global Forex in New York, puts it: There is no reason to expect the investment climate is going to change next week. The key drivers remain the same. The resurgence being seen in the virus is posing a speed bump in the re-opening and recovery process. The work of monetary and fiscal policy is not over. The low real and nominal interest rates are encouraging risk-taking by savers, and this means equities, commodities, and emerging markets.

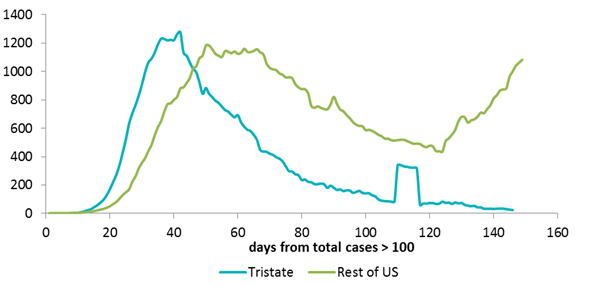

Until there is a vaccine that is widely available, flare-ups seem inevitable. The issue is how long it takes to bring it back under control. Even without new national lockdowns, the economic impact can be palpable. It may provide a speed bump of sorts to the pace of the recovery. On the virus, the recurrence in Europe and Australia is alarming, while there are tentative signs of hope in the U.S., where the number of new cases is stabilizing, with deaths running at a far lower rate than earlier in the year when the epidemic was at its worst in the New York City tri-state area. If we exclude the New York figures from the data, as in the chart below from NatWest Markets, we can see that the seven-day moving average in the number of deaths is nearly back to its peak from earlier in the year. If it avoids going much higher in the next few weeks, that would help the dollar:  Beyond that, nothing matters more than a vaccine. The difficulty of formally reopening an economy, or even of seeing economic activity return to normal levels, without one is growing ever clearer. That makes the search for a vaccine, which has intensified in the last few weeks, ever more important. On that note: Vaccines and Values As the hunt for a vaccine heats up, so do the ethical dilemmas. I did my best to summarize those issues here, in an essay we published Sunday. Several important points have been made in the day since publication. On the issue of whether scientists should use "human challenge studies," in which volunteers are deliberately infected with Covid-19 after receiving a shot of the tested vaccine, one critical issue is whether they can possibly give truly "informed consent" given the degrees of uncertainty. In particular, there is growing evidence that Covid can lead to ongoing damage to the heart, even in the healthy 20-somethings who would be allowed to take part in such tests. In the U.S., the fact that Eduardo Rodriguez, a well-known baseball pitcher, who is 27 years old and built like an ox, has been forced to abandon the current season with myocarditis following a Covid-19 infection makes clear that this could infect anyone. Both the volunteers and scientists I spoke to who back human challenge trials say they can deal with these objections. Most importantly, there would be no need for the research if there were no uncertainty. Anybody taking a role in such a test must know they are taking a risk. And that risk still appears to be of manageable proportions. But the issue does show that it will be difficult to speed up the process of approving a vaccine. "Vaccine nationalism" — the practice of governments of several large countries buying up rights to large supplies in advance, thereby potentially condemning developing nations to delays and higher prices — is also very contentious. One important point made in this edition of Cardiff Garcia's excellent The Indicator podcast on NPR is that vaccine production is necessarily distributed widely. Only a few countries have the capacity to mass-produce a vaccine, and they in turn rely on raw materials produced by only a few others. One widely used ingredient, for example, is found only in Chile and processed only in Sweden. So sharing might make some sense, even for those who defend "vaccine nationalism" as part of a government's obligation to look after its own citizens first. Then there is the possibility that those who don't get the vaccination find themselves effectively cut off from society. This is currently couched as a choice that it is fair to offer to vaccine opponents, many of whom work from home and home-school in any case. But some have no choice. One reader wrote me: I genuinely do not know if I can risk HAVING the vaccine. As a result of certain underlying conditions there are medicines I must not take, including paracetamol [acetaminophen] for example. I was warned in an email by my consultant "UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES" take altitude pills (and suffered altitude sickness as a result!). Malarial tablets fall into the same category. ...under your comment I would be banned from most activities. And there will be millions like me in a similar dilemma. How should this situation be addressed? This is a difficult question to answer. Suffice it to say that the virus and the vaccine to cure it threaten to create lasting divisions in a society that has already been badly divided by the pandemic. My main impression after spending two weeks immersing myself in vaccine development and the battles between bio-ethicists is that investors should beware of treating this as a process with binary outcomes, or even one with a finite outcome. It's quite possible that the first four or five vaccine candidates won't work. As the search goes on, it will get ever more difficult to recruit tens of thousands of people for each new test. It is quite possible that the first vaccines to be released for use will in fact still be effectively in the final stage of trials. There may be a "second-mover advantage;" the best vaccine may not come along for a while, or scientists may find better ways to apply the early vaccines. On top of all of that, there is the abiding problem of lack of trust. Many people don't trust their governments or scientists. Vaccines were already a focal point for distrust before Covid-19. A poorly run roll-out, or a series of highly publicized disappointments, or, worst of all, a premature roll-out that leads to serious side-effects, could all leave us worse than we started. It shouldn't be taken as a given that enough people will voluntarily take the vaccine to bring the virus under control. It goes without saying that this is a hugely important issue. All feedback is welcome. Survival Tips There is dreadful news from the isle of Corfu. Developers are ready to start building a new resort in the wild and beautiful Erimitis region in the north of the island, one of the most biologically pristine tracts of land left in Europe. This attacks the heart strings because Corfu, and particularly Erimitis, are at the heart of "My Family and Other Animals, by Gerald Durrell.

If you're unlucky enough never to have come across Durrell's Corfu trilogy, it is a memoir of five years spent on the island as a child in the 1930s. The author went on to become one of the world's leading naturalists, and his zoo on Jersey has saved many species from extinction. His older brother, a major character in the Corfu books, was the novelist Lawrence Durrell. The prose is breathtakingly rich, and everything is drenched in the Durrell sense of humor. Much of it is laugh-out-loud funny, and it's never sentimental; the best literary comfort food I have ever come across. It also spawned two TV series, the second of which, The Durrells, is viewable on Amazon, and a superb feature-length film.

His widow, Lee Durrell, also a great zoologist, is leading the voices of protest against the development. I hope she succeeds. The developers were able to buy the land for a ridiculously low price at the point when the Greek government was selling off everything it could in a desperate bid to balance the books. Financial crises have real and lasting consequences. In terms of survival tips: There's no more relaxing summer reading than Gerald Durrell; Greece has reopened, its beaches are empty, and if you're from one of the countries whose people can go there, I would strongly consider it. Enjoy the week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment