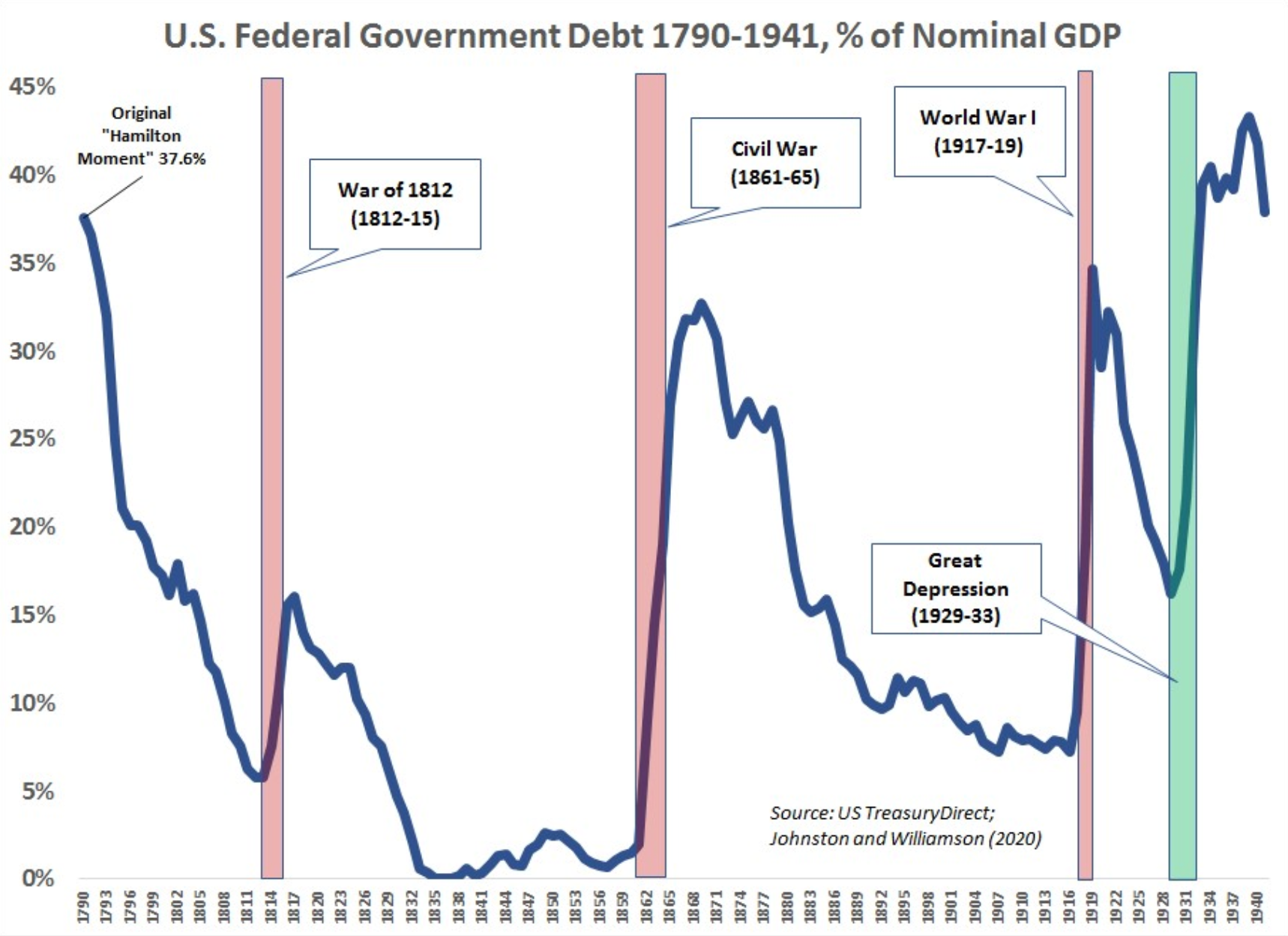

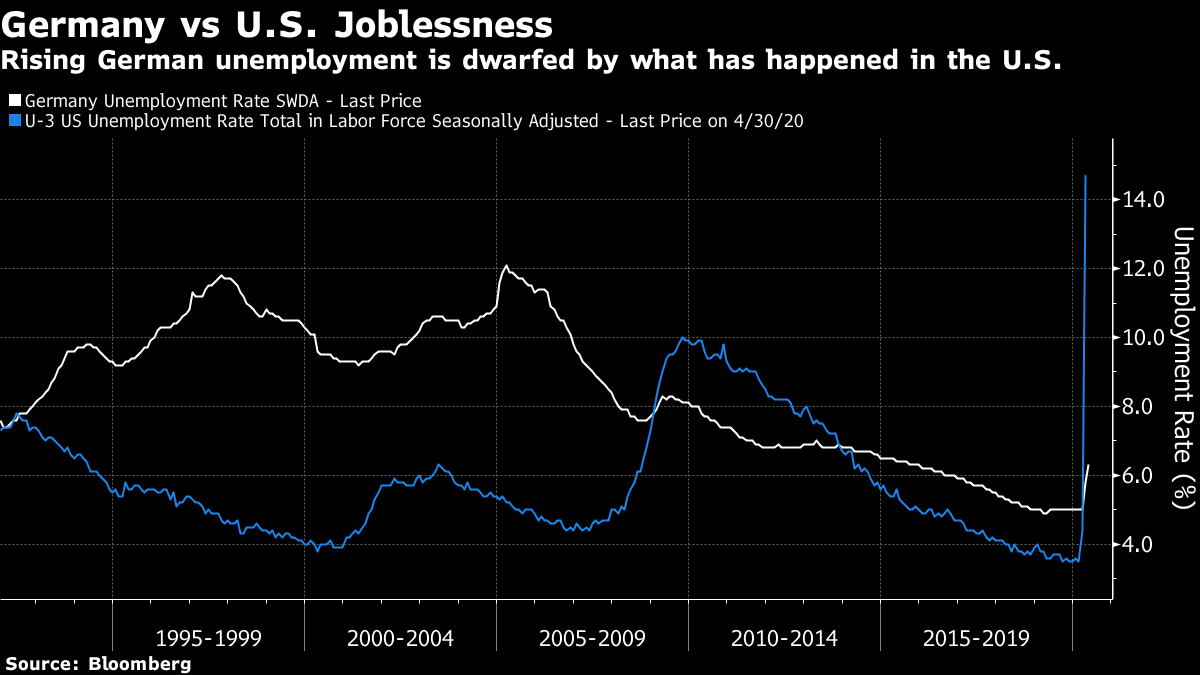

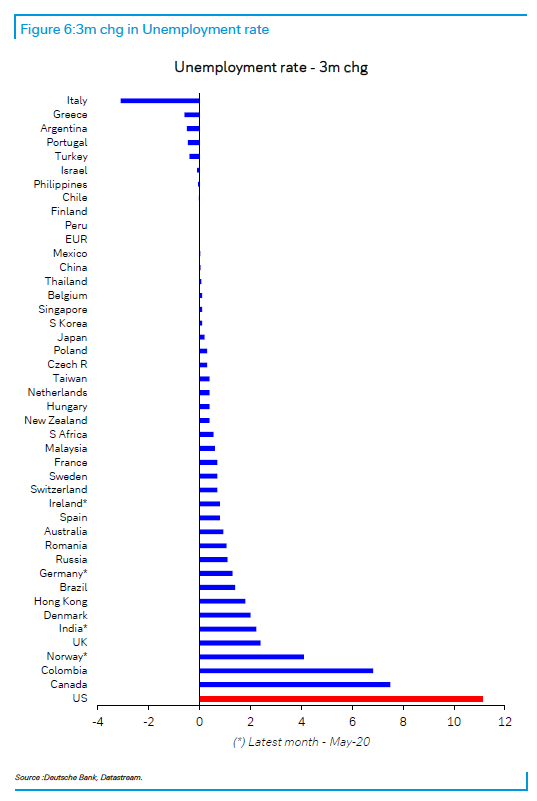

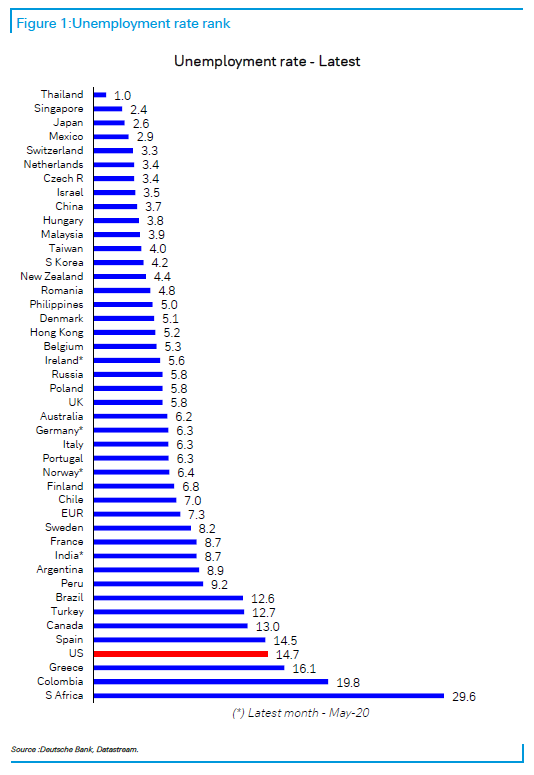

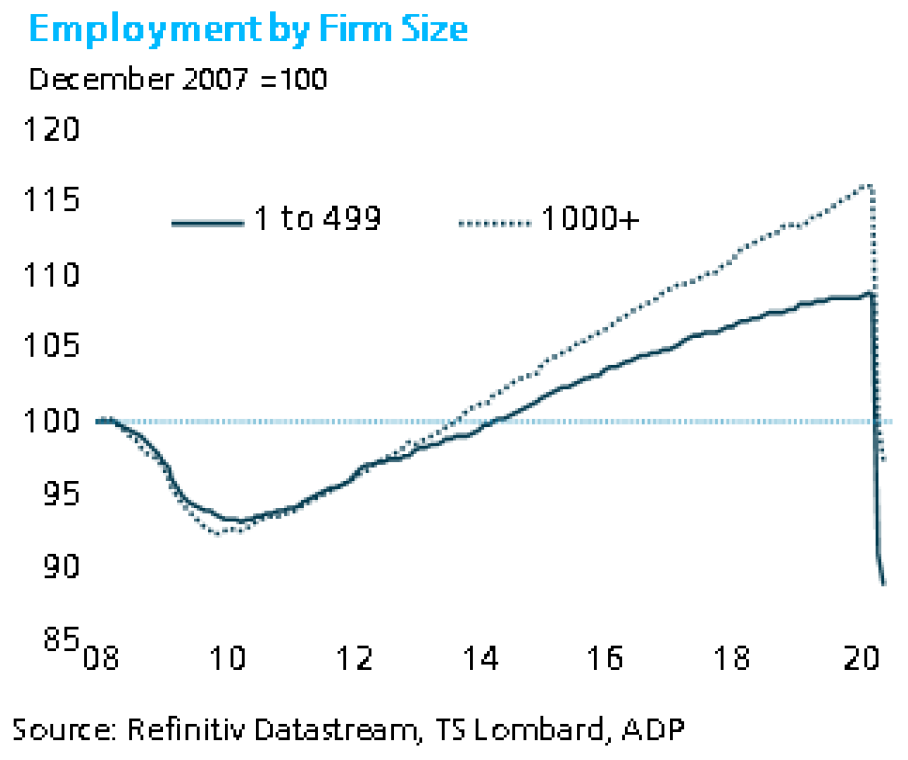

Hamilton Goes to Berlin Europe is having a good crisis. This is a small mercy for which we should be thankful; and it might mark a historic moment in the European project. Europe's financial and economic problems boil down to two. First, it has failed to grow for many years, lapsing into a "Japanified" disinflation. Second, it faces an existential crisis surrounding the euro, adopted in 1999. It is backed by a common monetary policy, executed by the European Central Bank, but fiscal policy is left to member countries. Ever since the global financial crisis of 2007-09, Europe has been dogged by the imbalances created by its own incomplete architecture. These crises are interrelated, and both tend to find their expression in a weak euro. As we entered the year, the crisis of confidence in the euro zone's structure appeared almost to have been resolved; but the fear of a deflationary morass had become overwhelming. Then came Covid-19. This is what happened to 10-year inflation expectations in Germany:  This number is improving but is still barely up to its lows from previous deflation scares of the last decade. For the threat to the euro's existence, the critical measure has long been the spread of peripheral countries' bond yields over German bund yields. First Greece and then more recently Italy have been the focus. Entering the year, both country's spreads were roughly back to where they were before the sovereign crisis began a decade earlier. Then Covid-19 arrived.  Greece's efforts to limit the virus have been successful, so far at least, while Italy has been one of the worst affected countries on the planet. A big economy with a huge debt market, Italy is now the eye of the crisis. In the last three months, things have improved. The European Central Bank has fired its bazooka, and on Thursday confirmed that it would be launching even more. Asset purchases under its so-called Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, or PEPP, have been increased by 600 billion euros ($682 billion) to 1.35 trillion euros. This was more than expected, and brought down Italian yields sharply. Such aggressive monetary policy might often be bad for a currency. In the case of the euro, however, investors believe these tactics are necessary to avert a slump, and the ECB's announcement helped spur further appreciation. It is now on its best run in almost a decade, gaining 4.5% versus the dollar since May 25. Germany, whose determination to maintain fiscal austerity is at the center of the euro zone's problems, is now moving ahead with a 130 billion euro stimulus program, which chancellor Angela Merkel described as "courageous and decisive." These measures give Europe a more coherent response to the pandemic than many thought possible. Enter Alexander Hamilton. America's first treasury secretary is in vogue thanks to the musical written by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Arguably his most lasting achievement was to persuade a dubious Thomas Jefferson to accept collectivizing states' war debts in the federal treasury. This led to the bond market (remarkably, Jefferson even opposed the notion of being allowed to sell a government bond for a profit or loss), and to the federal United States as it exists today. Now, the financial world is awash with speculation that we have a Hamiltonian moment for the euro zone, which will bring its federalist destiny. The French and German governments have made a proposal for 750 billion euros in bonds to finance coronavirus relief that would be raised in common, not by any constituent state. The comparison is obvious. Is it justified? The arguments that it is are, first, that in proportion it is as big as the original Hamiltonian assumption of war debt. This chart is from a great Twitter thread by the Peterson International Institute of Economics' Jacob Kirkegaard. He makes the point that the proposed bond raising, while only 5%-6% of gross domestic product, would in fact be as high as U.S. federal borrowing ever reached (outside of wartime) in the 130 years between the Hamilton moment and the Great Depression:  Another strong case in favor comes from Anatole Kaletsky of Gavekal Economics. First, he points out, the bonds will be issued by the EU in its own name, avoiding any confusion of joint guarantees. Second, and perhaps most important, this implies tax-raising power for the EU, beyond its current income from customs duties and a small share of value added taxes. Kaletsky suggests that this will need to be raised from "economic activities which transcend national boundaries" — so maybe a tax on carbon, financial transactions or digital activities. Finally, he points out, the proposal allows the EU to leverage itself. Interest rates are at rock bottom, so this could soon become a mechanism for dealing with far more than coronavirus relief. A second school of thought holds that this may be a key moment for Germany, rather than for the EU as a whole. Former colleagues Martin Wolf and Philip Stephens both make this argument, as does Adam Tooze, director of the European Institute at Columbia University. He points out that the move has much to do with the German government's attempt to deal with it own constitutional court's ruling that the ECB's bond purchases violated the country's constitution. It also reflects the revival in the political fortunes of Merkel's CDU party in recent months, giving it the power to push through unpopular measures. But he suggests that this is seen in Germany as a temporary response to an extreme crisis, not the start of a new version of Europe. Tooze points to obstacles ahead. This cannot happen until next financial year. Italy is on its own for the rest of this year . That is a big problem. The "frugal four" countries, led by the Netherlands and Austria, oppose the idea and will try to extract concessions. And tax-collecting could be a flash point. If Germany tries to catch up with Italian "tax avoiders," there is friction aplenty ahead. Rather than a Hamilton moment, Tooze suggests this is an imaginative fix to help Europe get through its problems. But that is still a big deal, and much better than previously feared, while the long-term impacts could be profound. As for the euro, it is unlikely to keep rallying like this for much longer; but money is still leaving the dollar as risk appetite returns, and the euro can be expected to maintain its upward trend for as long as the proposal to raise coronavirus bonds remains on course. Unemployment Friday sees the announcement of the U.S. non-farm payrolls for May. Whatever the figure, it is a racing certainty that U.S. unemployment will be much higher than that of Germany. 'Twas not always thus. Germany suffered high unemployment in the wake of reunification; and it was largely the country's problem with joblessness that prompted the ECB to set low rates, leading to property bubbles in the periphery before the 2007-09 crisis. Now, the rise in German unemployment is dwarfed by the increase in the U.S.  This is the result of a policy choice, and it will be a while before we know who got it right. In much of Europe, governments have paid companies to keep idled workers on their payroll. In the U.S., it is easier for companies to lay off workers, and aid has followed workers, not companies. The U.S. has more flexible labor markets that aim to improve competitiveness. The hope is that companies will rehire workers swiftly when the economy reopens. International comparisons of employment statistics are difficult. Countries have differing definitions. Even so, the way U.S. unemployment has risen sticks out. This chart is from Alan Ruskin, investment strategist for Deutsche Bank AG:  Meanwhile, the official unemployment rates (which again, aren't always directly comparable), show startlingly high U.S. unemployment, even before May's figure:  Europeans may yet have a problem paying for the help they have given companies; but the U.S. has also taken a risk. Lay-offs allow cost cuts during the lockdown — but how many people will be rehired when the economy reopens? This chart from Steve Blitz, chief U.S. economist for TS Lombard, uses ADP data and shows that unemployment for companies with more than 1,000 employees isn't as bad as in the last recession; but for companies with fewer than 500 employees, it is already much worse:  The health of small companies matters hugely to the health of the American economy, and their plight is largely invisible when looking at the S&P 500, whose companies dominate debate. If smaller American companies can get back on their feet quickly, hindsight may judge that U.S. policy worked better than the approach taken in Germany. But if not, not. Survival Tips It's getting hot and sticky in Manhattan. This contributes both to hopes that the virus will have a seasonal dislike for summer weather, and to an eagerness for many people to get on to the streets and protest. So I suggest listening to Ghost Town by the Specials, the haunting anthem of the riots that tore across the U.K. in the summer of 1981. The Guardian reckons it is the second-greatest U.K. Number One single ever. The Guardian's critics are about to reveal their number one. Only one record per artist is allowed in their top 100, and I assumed the top spot would go to an early Beatles song — I was thinking I Want To Hold Your Hand. But She Loves You (perfectly good choice) came in at number three. The Guardian have already listed their favorite songs by the Rolling Stones, Abba, David Bowie, Queen, the Kinks, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Beyonce and any number of other great acts. (And as all good trivia buffs know, neither Led Zeppelin nor The Who ever had a U.K. number one single, so they're out). Who will the Guardian make number one? Potential candidates include Pink Floyd's Another Brick in the Wall, which is a great song by a seminal band, but I can't see putting it above the Beatles. Faintly possible is I Don't Like Mondays by the Boomtown Rats. They might go withImagine by John Lennon, giving him two entries in the top three. Or possibly God Save the Queen by the Sex Pistols, which went to number one in the NME chart in 1977, just as the Queen was celebrating her silver jubilee, but didn't make it to the top of the official BBC chart, sparking widespread conspiracy theories of a fix. But my best guess is that The Guardian will have gone with You've Lost That Loving Feeling, or maybe Unchained Melody, by the Righteous Brothers. Darn good songs, particularly the former. All of these songs, possibly with one exception, didn't make the Guardian's top 100, which is strange given some of the very questionable records that did.

I still think they should have gone with an early Beatles song. And as you've probably guessed, I've spent almost as long trying to second-guess the musical taste of a bunch of rival journalists as I devoted to analyzing the future of the euro zone. Such endeavors, I maintain, are good for your mental health, and your survival.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment