| Welcome to the Weekly Fix, the newsletter that's never underestimated the predictive power of the yield curve. Except for that one time in March. –Emily Barrett, FX/Rates reporter. Rampant Curve The U.S. yield curve is on a tear. So much has it leapt ahead that it's even sparked talk about the Federal Reserve putting a leash on it. (More on the leash in a bit.) Long-dated Treasuries have taken the brunt of a Treasury market selloff as the U.S. economy gradually reopens. The benchmark 10-year yield hit a significant milestone Thursday, pushing above 0.78%, the top end of the range it's held since the end of March. That set a fire under options markets, spurring demand for puts targeting as high as 0.95%. The last time the slope of the Treasury curve was making news, it was upside down. Alarm bells started ringing across global markets in March last year as the rate on long-dated Treasuries fell below those on shorter maturities – a reliable signal that a recession is coming within the next year or two. At the time, skeptics had perfectly good reasons for doubting the curve's strength as a signal (in a low-interest rate environment, with the tightest U.S. labor market in a generation), but all bets were off with the advent of Covid-19, and the prophesy was fulfilled. This week, the five- to 30-year curve reached its steepest since February 2017, with the spread pushing above 122 basis points. This climb bears little resemblance to back then, when excitement over tax cuts and deregulation conjured up visions of an historic economic expansion.

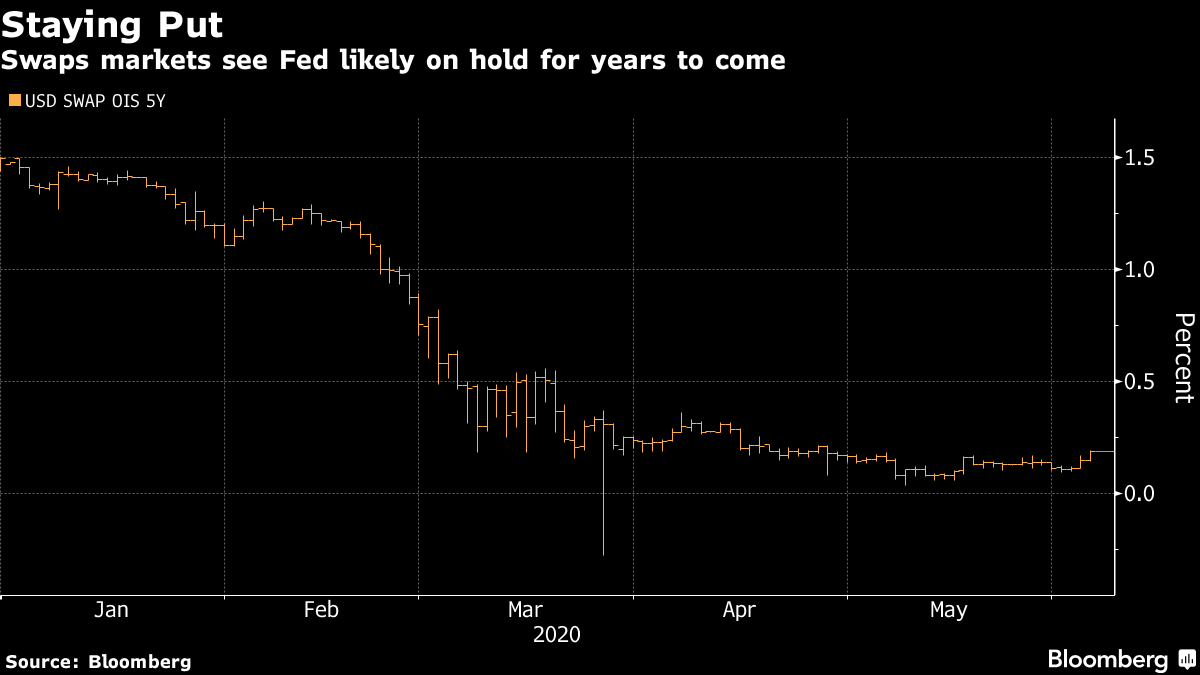

The them now is that the world's biggest bond market is reshaped by the massive combined forces of Fed interventions and government borrowing. Futures pricing suggests the target policy rate will be at the zero bound for at least the next five years, and that's keeping front-end yields pinned down. The prospect of more government borrowing to lift the economy out of the deep recession, meantime, is driving up the longer end. Some are even talking about the emergence (at long, long, long last) of inflation. But that's tough to reconcile with a 10-year breakeven rate around 1.2%, which implies the Fed's preferred inflation measure will be little more than half the 2% target over at least the next decade.

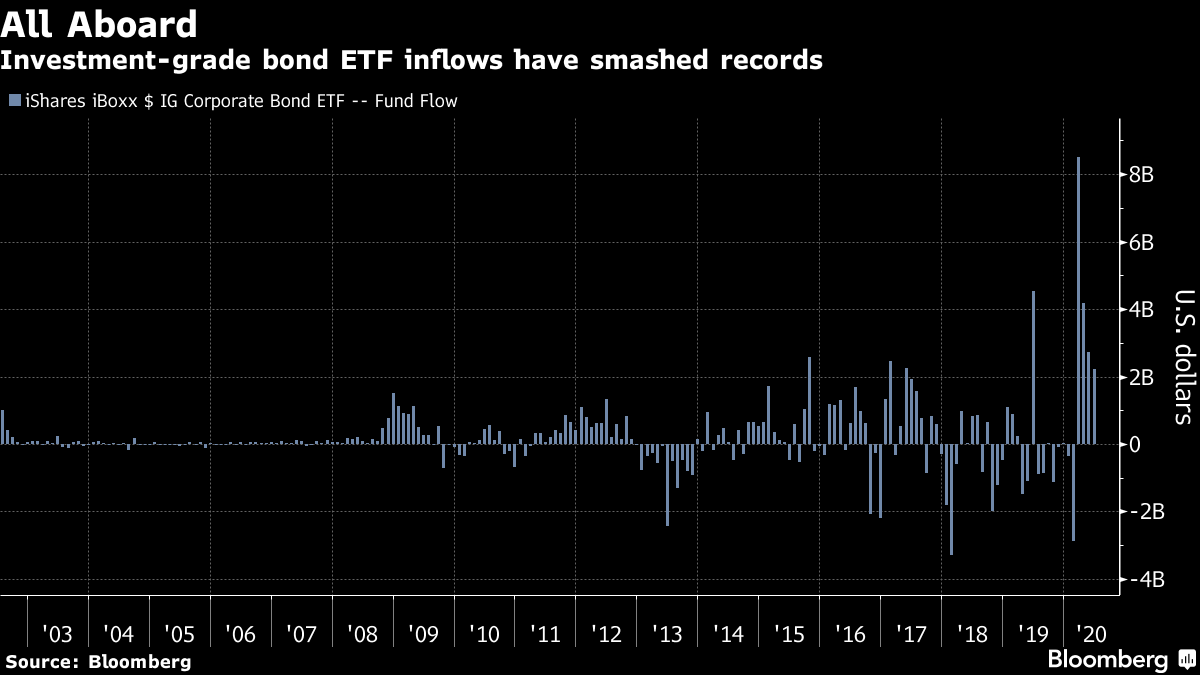

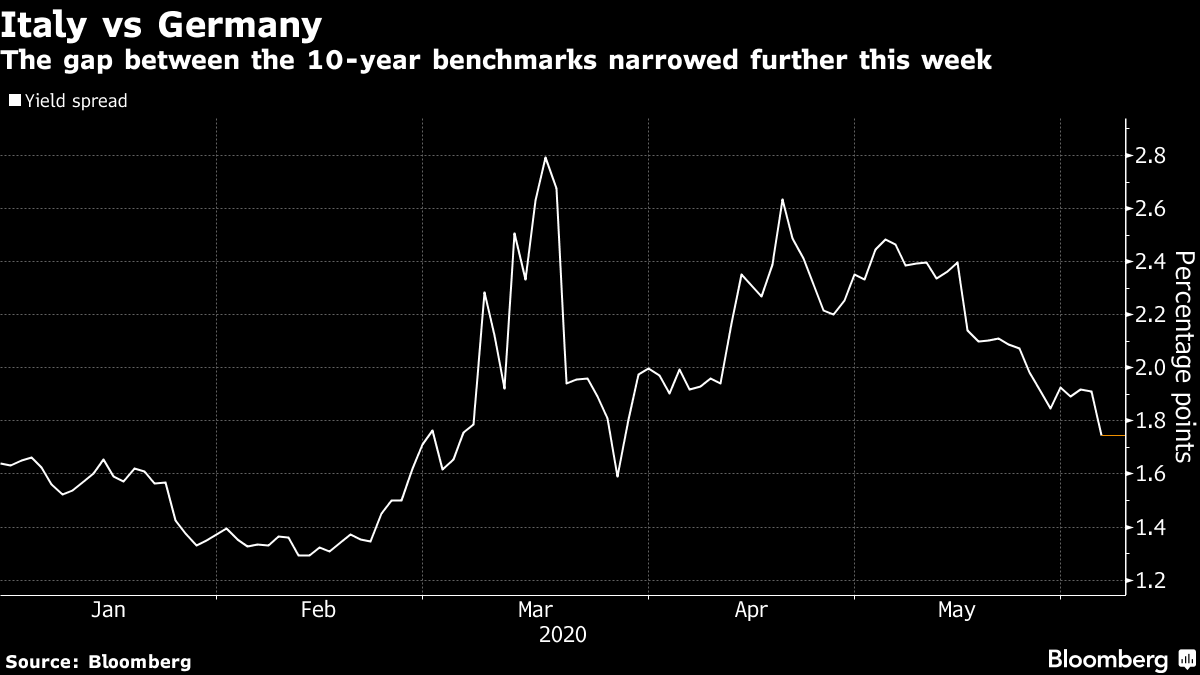

The stamina of this long-end selloff is questionable, given the vigor with which investors have bought any dips in recent memory. But Wells Fargo, for one, sees it building. The bank's strategists say 10-year yields could climb as high as 1.5% by year-end. Fed Leash But the curve's behavior has stoked expectations that the Fed is preparing to exert some sort of yield-curve control. A slim majority of economists in the past week's Bloomberg survey say they see the Federal Open Market Committee announcing specific targets for yields before the year is out. That said, none of them anticipate further guidance on its plans for asset purchases at next week's meeting. The Fed isn't short of templates for such a move. The Bank of Japan has been tethering the benchmark 10-year yield since 2016, and the Reserve Bank of Australia set a level for the three-year rate in March. And of course the U.S. isn't new to the policy, having aggressively managed its borrowing costs in this way as part of its World War II funding effort. BlackRock's Bob Miller, head of Americas fundamental fixed income, isn't convinced that explicit YCC is in the Fed's sights just yet, given the uncertain path for the economy and the reopening. If all goes smoothly enough, Miller says Powell could simply maintain the current guidance, with flexibility toward asset purchases, as long as the structure of rates looks "something like it does today." Explicit YCC is his risk case. UBS economist Seth Carpenter and team stand, by contrast, see three big announcements Wednesday: 1) a commitment to hold the fed funds rate at zero for at least three years; 2) front-end yield curve control; and 3) a switch to monthly, open-ended quantitative easing. They counter pushback on the aggressive timing by drawing attention to Chair Jerome Powell's potential longer-term vision: "One key question is `why not wait?' And indeed, the FOMC could wait until a later meeting. Consider at least these two points. Chair Powell has been clear that he worries about the downside risk to the economy not just in weeks and months, but quarters and years. Information between now and September will confirm the medium-term trajectory. Second, none of the options under consideration for their strategic review will be cut off by acting now. In fact, it avoids a communication mistake that could tighten financial conditions if they do not act.'' Risk Assets Rip Markets are perhaps responding to Powell's assurance that an economic rebound is likely in the second half of the year, more than heeding his warnings about the longer-term challenges. It's been said a lot lately, but it bears repeating here. The contrast between the markets and the main streets of the U.S. is painfully stark. As job losses have climbed further into the tens of millions and protesters in every state gather in anguish and rage over the death of George Floyd, asset prices are surging. The Nasdaq has approached its record high and other indexes aren't far off, high-grade bond yields are closing in on record lows and a stampede back into popular corporate bond ETFs has pushed their assets to all-time highs. (For Wall Street's response to the protests, see this story: "It's 2020 and enough is enough. We can no longer be silent.'') The corporate bond activity prompted Matthew Bartolini, who looks at ETFs at State Street Global Advisors, to write: "The greatest trick the market ever pulled is trying to convince investors that this recession doesn't exist."  But it's clearly spurring a Darwinist regime in corporate America, where market access is the key to survival. Those able to load up on debt have catapulted issuance to $1 trillion already this year, while bankruptcy filings have mounted to levels unseen in the past decade. Even those that can borrow now may struggle to meet debt payments. Ex-New York Fed chief Bill Dudley raised the specter of financial stability this week more publicly than many of his peers still at the central bank have been inclined to. Speaking of high-yield debt, he said in a Bloomberg Television interview, "for the Federal Reserve to intervene and support those asset prices, is basically creating a little bit of a moral hazard in the sense that you're encouraging people to take on more debt." PEPPed Up The European Central Bank decided to keep loosening the liquidity spigot. With less than a third of the 750-billion-euro ($850 billion) pandemic debt-purchase program disbursed, the central bank raised it another 600 billion. ECB President Christine Lagarde appeared to have little choice. Market expectations leading up the meeting had settled on a 500 billion increase. So barely three months after Italian yields vaulted on her observation that the central bank was ''not here to close spreads,'' the 10-year had reversed much of its subsequent widening to Germany.  High expectations of support also helped Italy sell bonds, as it did this week, to a rapturous reception. Indeed, supply is the operative word now that the ECB is proving itself more than a match for the government spending in the pipeline, and with another round of targeted longer-term refinancing operations toward the end of the month. Bonus Points Jeffrey Sachs is not optimistic. John Authers explains the term `Fill Your Boots'. Delayed bond-trade reporting meets stiff opposition. No means no -- Australia's bond market is catching a wave of investment with the central bank's stand against negative rates.  The same can't be said for the mortgages sector, which is off to its worst start since 2013 despite Fed help. Learn more about birds. Movers and Shakers (In this new, periodic section, The Weekly Fix will be spotlighting personnel moves in the fixed-income world and its environs. If you have tips or suggestions, please write ebarrett25@bloomberg.net) Hedge funds are on a poaching spree, targeting wounded rivals, and distressed debt specialists. Financial hiring gets tougher in social distancing era. Billionaire Izzy Englander's Millennium Management has hired Priya Kodeeswaran... ... and added 100 people since early March, including quant experts Matthew Rothman and Gary Chropuvka, who was tapped in April to lead WorldQuant. Goldman Sachs named Nicole Pullen Ross as regional head of the bank's private wealth-management arm in New York. Rami Hayek, the former Asia-Pacific head of institutional clients coverage at HSBC Holdings Plc, was hired by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority as a senior adviser. Note: A correction to last week's issue, in which the name of Lazard AM portfolio manager Denise Simon was misspelled. |

Post a Comment