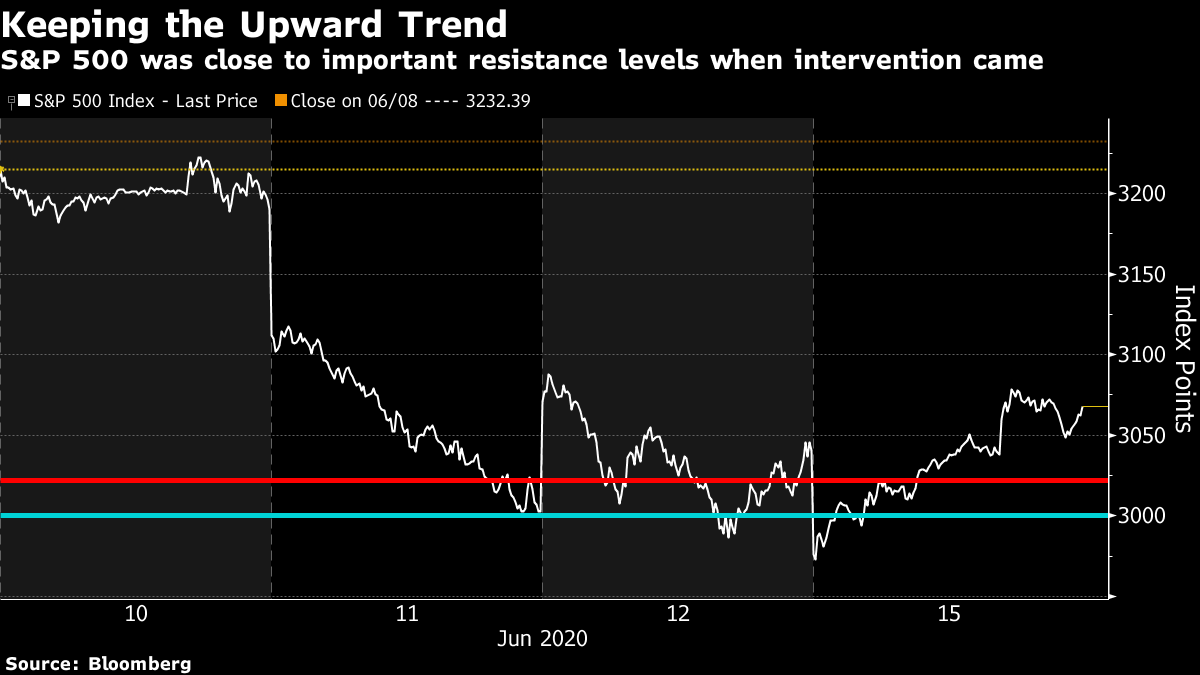

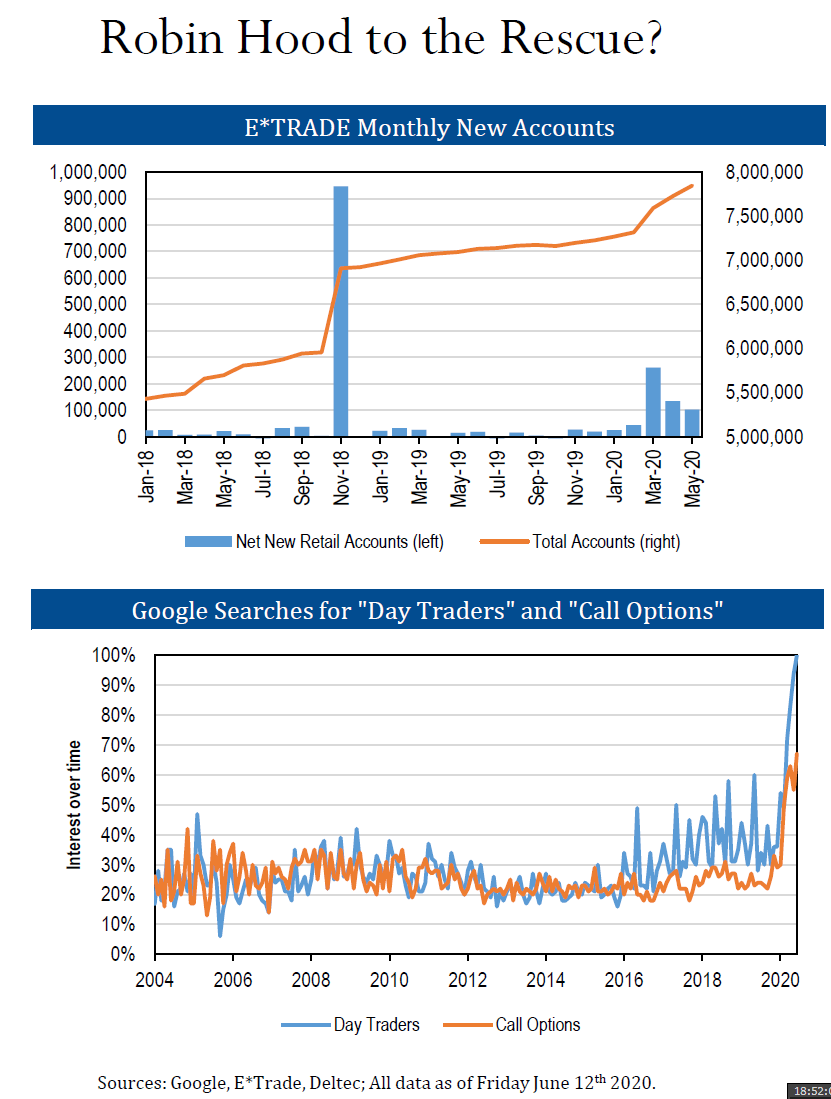

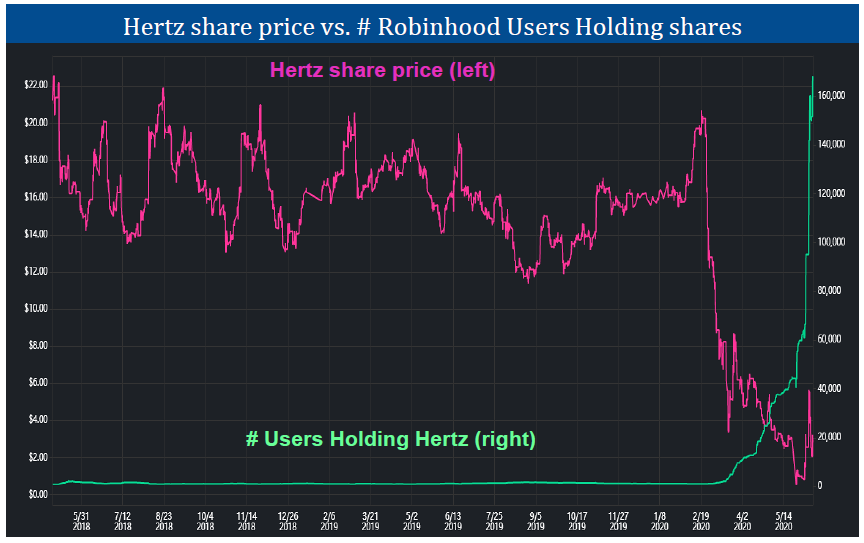

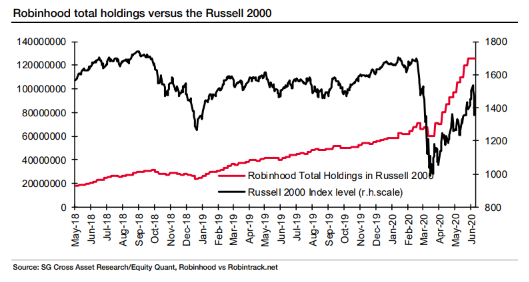

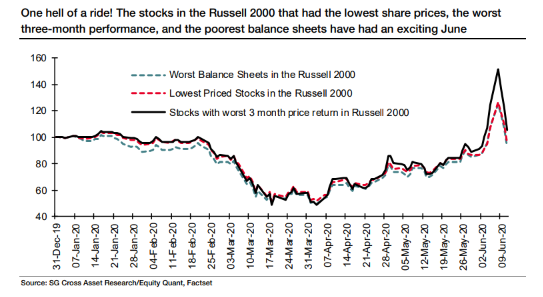

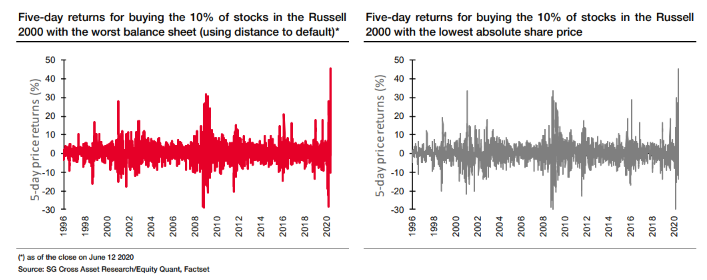

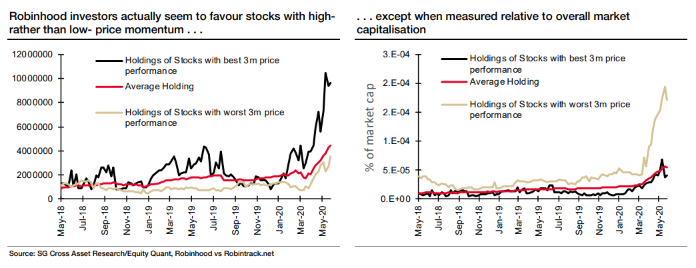

Changing the Narrative Not long ago, I thought today's newsletter would have to tell the story of Robin Hood vs the Invisible Enemy. In other words, how the army of retail investors who have flocked to commission-free trading offered by robinhood.com and others would fare in conflict with the apparent resurgence of the coronavirus in a range of countries (including all the BRICS — Brazil, Russia, India and China) and red American states. Would the retail traders' naive optimism (or sensible homespun wisdom, depending on your point of view) triumph? Or would a sensible grasp of the reality (or unreasoning panic, again depending on your point of view) that the virus remains unbeaten emerge victorious? As it turns out, it is necessary instead to write about the Fed coming to the rescue. Again. More on Robin Hood below; the Invisible Enemy will have to wait until tomorrow. The latest act by the Federal Reserve was announced at 2 p.m. It has moved from buying exchange-traded funds of investment-grade bonds to purchasing individual bonds. The news came as a surprise, and helped LQD, the best-known ETF holding U.S. investment-grade bonds, to hit a new record. This is how LQD's share price has fared over the past two years:  If this doesn't look to you like a market in urgent need of a rescue financed with public money, I would have to agree. Further, the timing looks awful, if the Fed wants to avoid the impression that it is just attempting to provide a "put" under share prices, and intervene to keep them up. I have no reason to believe that this is what they are doing, or what they think they should do; but it is unfortunate that they made this announcement just when it looked like the market might be in need of a put option. The move came after a rocky start to the week's trading on the stock market, which itself followed a difficult end to the previous week. At the open, the S&P 500 was below both the 3,000 level and its own 200-day moving average, marked with horizontal lines:  It had already recovered nicely before the Fed's announcement, which was rewarded with a nice vertical increase. If there really were a Powell Put, this is how it would operate. Meanwhile, the case for intervention is slim, as Brian Chappatta explained forcefully for Bloomberg Opinion. There was no way the Fed needed to do this. This chart shows the yield on corporate bonds rated BAA (the lowest investment grade) by Moody's Investors Service, going back to 1986:  The Fed chose to make this intervention when yields were below 4%, a level unthinkable until the past year. Bond issuance, as has been widely reported, has gone through the roof in the last few months. The market is operating well, if not too well. If we look at the spread between between corporate bonds and equivalent Treasuries, again it is hard to see why the Fed needed to announce unprecedented action right now. Spreads are higher than they have been for a few years; but they remain tighter than at the worst of the crisis, tighter than at virtually any point during the Obama administration, and far tighter than at the worst of the crisis in 2008, when the Fed's desperation tactics never extended to buying corporate bonds outright:  This may simply reflect a sense of obligation to follow through on earlier announcements. But that isn't how central bankers tend to run their relationship with markets. Probably the single most famous pronouncement by any central banker in the last decade was Mario Draghi's promise, at the worst of the euro zone's sovereign debt crisis, to do "whatever it takes" to save the euro. The president of the European Central Bank was never called on to follow through. Remarkably, the market never tested the ECB's resolve, and his words proved enough to tide the euro zone through. Words alone, and the narrative of determination Draghi had created, proved to be enough. Understandably, therefore, he didn't commit huge sums of money to buying Greek, Italian or Spanish bonds. It would have been wise for the Fed to follow his example. In the short run, it grows ever harder not to buy stocks. In the long run, this will look like a mistake. On the Subject of Narratives….  I spoke to Robert Shiller, Nobel laureate and writer most recently of "Narrative Economics," for a webcast hosted by Natixis Investment Management. If you want more on the importance of narratives to markets, and to economics more generally, I hope the hour's conversation will be worth a listen. You can watch a replay here. Robin Hood and Portnoy's Complaint And now to another narrative. For weeks, market talk has been dominated by Robin Hood and his merry men, and particularly Portnoy's Complaint. Led by Dave Portnoy, of whom I hadn't heard until a few weeks ago but who has more than 1.5 million followers on Twitter and big support among sports betters, retail investors are boldly going where others fear to tread. Portnoy has no lack of self-confidence:  Robin Hood is a convenient tag because the resurgence in retail was sparked by robinhood.com, which started offering commission-free trading last year. All the big discount brokers are seeing a rise in uptake. Meanwhile, social media is full of excitement, as novices eagerly find out how to use options. These charts are from Deltec:  This has led to some absurd situations. Most famously, retail investors so bid up the stock of car rental group Hertz Global Holdings Inc., which declared bankruptcy last month, that the company is offering a new issue of stock — every penny of which will probably have to go to pay off creditors. That situation is so absurd as to be almost beyond parody, although my inimitable colleague Matt Levine did a good job.  So we have our narrative then. A bunch of doofus retail investors, led by the kind of guy who dominates the conversation at the bar after the game, are doing some dumb things and losing lots of money. Except, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. research finds that they are in fact doing a great job of stock-picking. This is from the latest weekly report by David Kostin, the investment bank's chief U.S. equity strategist: In recent weeks, investors have focused on a different type of disconnect between Wall Street and Main Street: The relative performance of institutional and retail investors.Since the March 23 low, our Hedge Fund VIP and Mutual Fund Overweight baskets have each returned 45%, outpacing the 36% S&P 500 rally by 900 bp. However, a basket of the most popular retail trading stocks (GSXURFAV) has returned an incredible 61%. As we highlighted in May, broker data reveal a tripling of retail trading activity as the market declined. Here it is in graphical form:  Meanwhile, the quantitative team at Societe Generale SA, not often regarded as soulmates of Goldman Sachs, independently established that Robinhood clients are great market timers. This maps the growth of Robinhood users' total holdings in the Russell 2000 with the performance of the small-cap index. Their timing was impeccable:  So there are two assumptions rebuffed. Personally, I have been reluctant to believe that this latest resurgence of retail activity is anything like its famous antecedent at the end of the 1990s. Back then, as a market reporter, covering each break would involve phoning Fidelity, Vanguard and Charles Schwab to find out what their clients were doing. They almost invariably bought on the dip, and made this a self-fulfilling prophecy as the wall of retail money pushed stock prices back up. This time, I thought, was different. Two decades ago we were in a demographic sweet spot as baby boomers were aging and piling money into 401(k)s and IRAs in a belated bid to boost their retirement income. Most boomers are now retired, while the impact of two major financial crises in 2000 and 2008 deterred them from trying to play the market. The culture in the late 1990s was saturated with day-trading and the opportunity to get rich on the exciting new internet. Today's environment is nothing like that. I would still hold that retail money isn't going to have the same effect this time. The demographics are different, and much money is in any case now tied up in highly prescriptive asset allocation plans. Pension sponsors have worked out that giving savers the chance to switch their money on a daily basis between hundreds of different funds was a bad idea. But SG's research still makes clear that retail money is having a real impact at the margin. The day traders have piled into the cheapest stocks with the worst balance sheets in the Russell 2000 in recent weeks — and an epic "dash for trash" has resulted. What you see in this chart isn't the result of trading by hedge funds or big institutions:  And while a "dash for trash" like this isn't uncommon after a major market break, this one is on a bigger scale than any predecessor. As SG shows, five-day returns for the small-cap stocks with the worst balance sheets and the lowest price are without precedent. These are dreadful stocks, and Robin Hood came to their rescue:  Robinhood's merry men really have turned around the market. As this chart shows, they have had a huge impact on the stocks with the worst performance over the preceding three months, where the weight of their money has made the greatest difference:  It is heartening to see retail money playing an important role in driving the market, for the first time in two decades. It is even more encouraging to know that retail investors have timed the market and picked stocks better than the professionals. But I'm still enough of a curmudgeon to think that this will end in tears. Democratizing finance is great in principle; it tends to work out the opposite way in practice, with the poor snatching losses for themselves that would otherwise have been suffered by the rich. Survival Tips One way to survive is to get back into the groove of the Bloomberg book club, which we are now going to revive. The book I had just recommended before the virus so rudely interrupted us wasFactfulness by the late Hans Rosling.  It's a truly great book, written by an expert in public health and epidemics, aimed at showing that the world is much better than we think it is. It also weighs in at less than 200 pages, and could scarcely be more relevant to our current predicament. So let us finally get around to reading it. We will aim to hold an online discussion on the terminal in the week after the July 4 break. Enjoy. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment