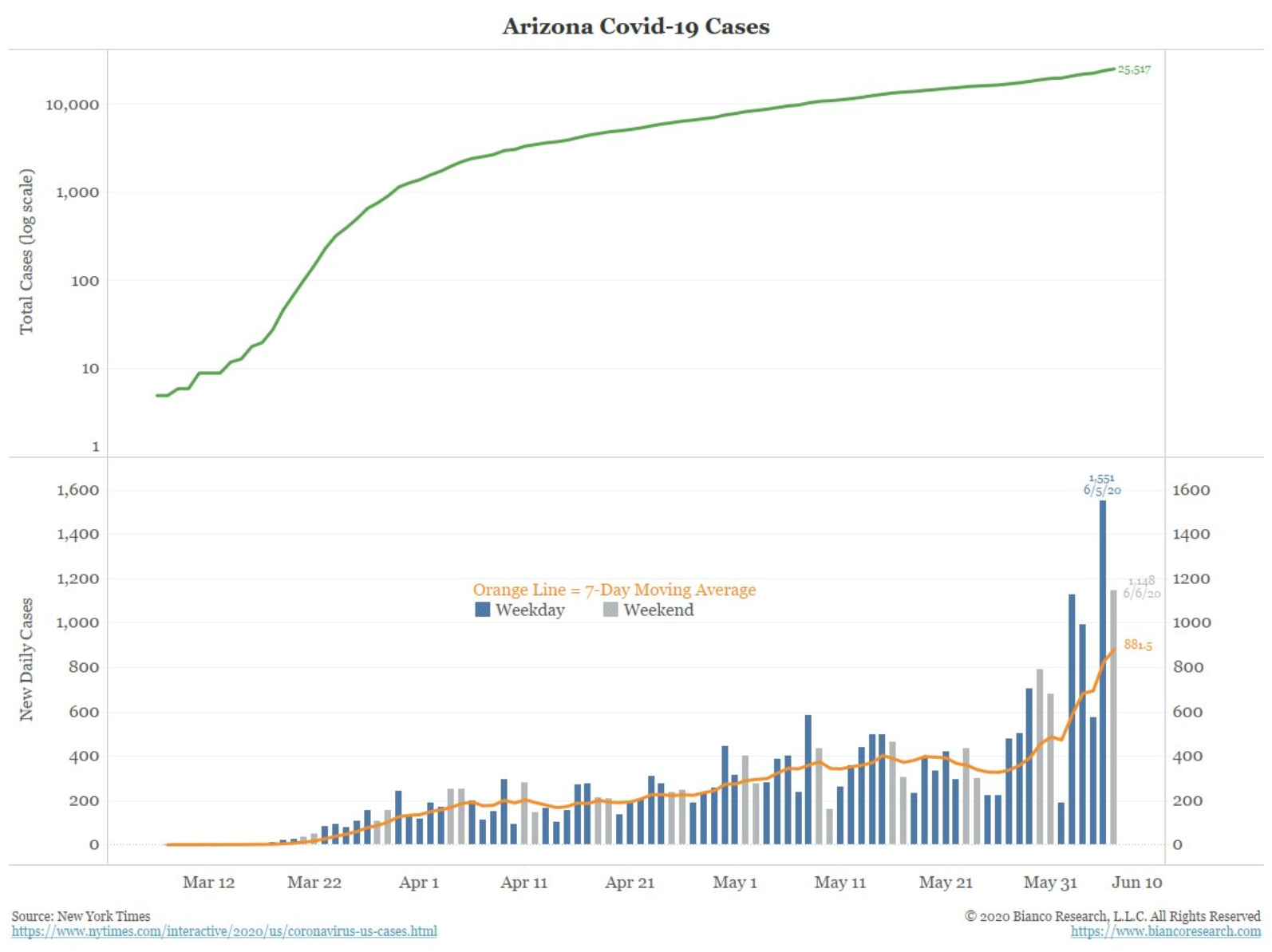

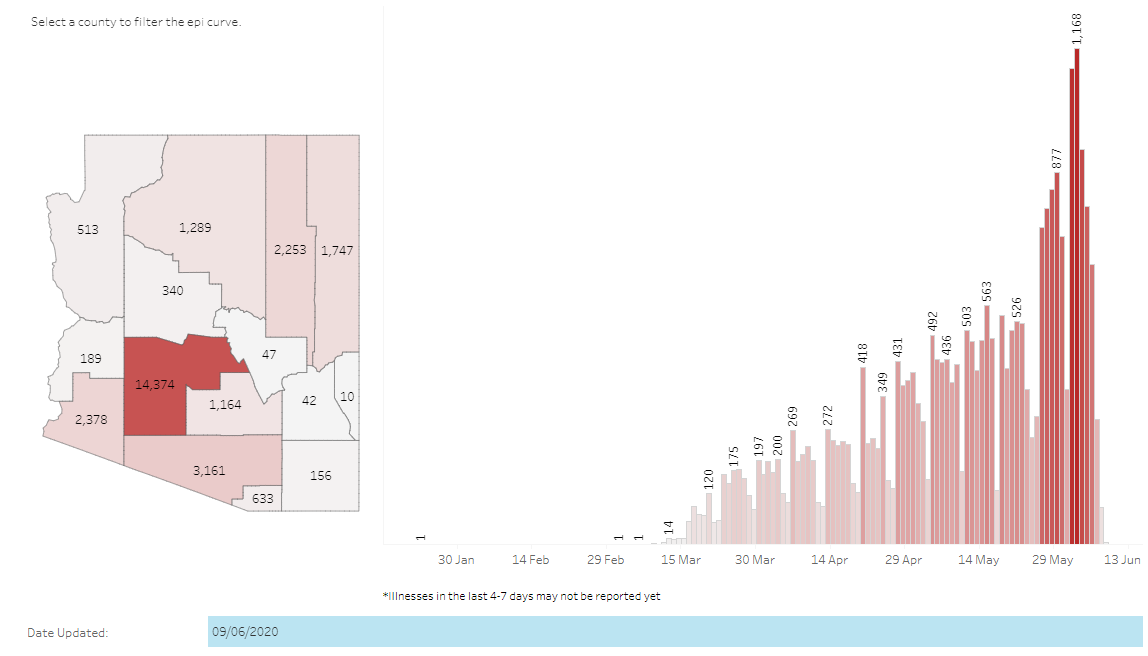

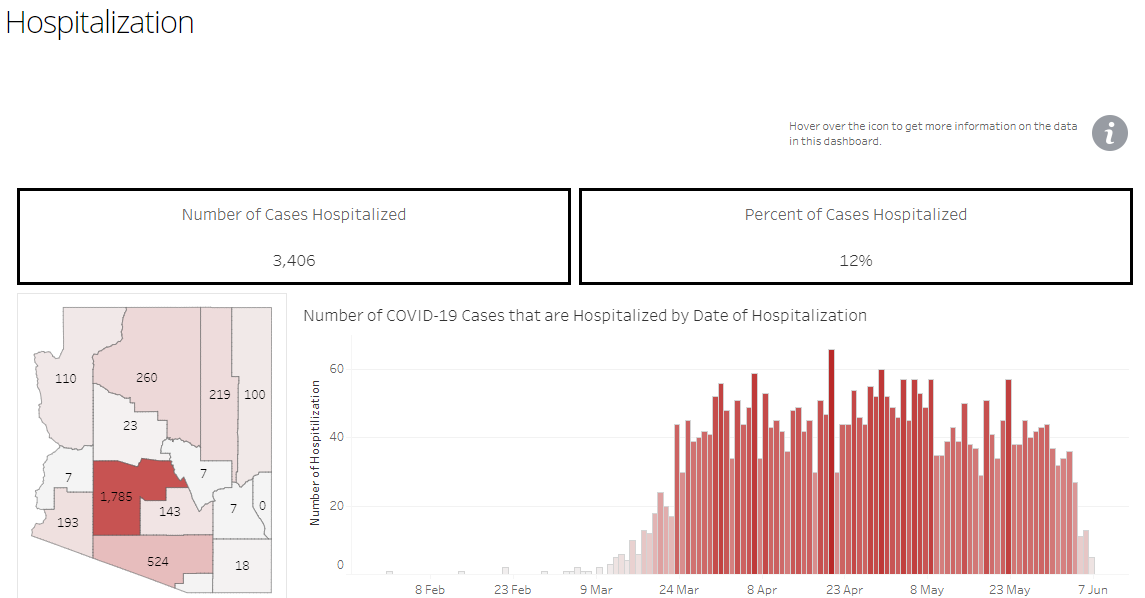

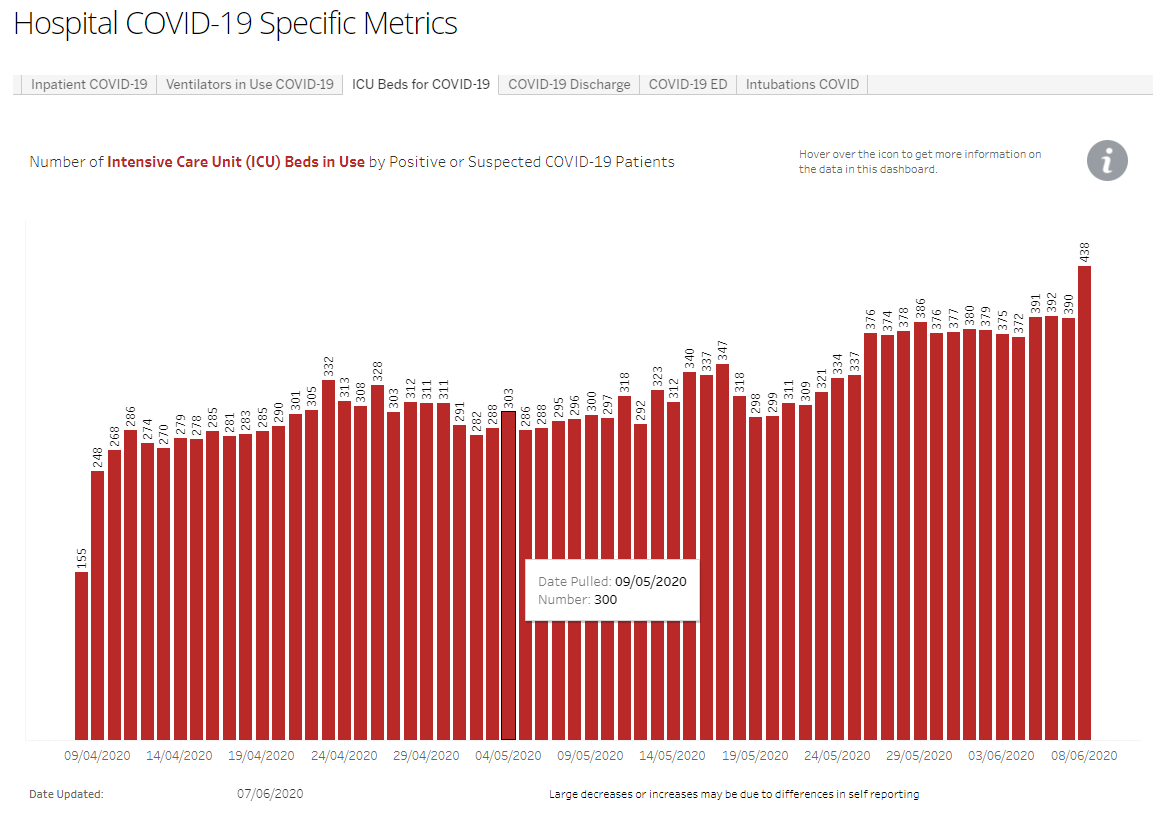

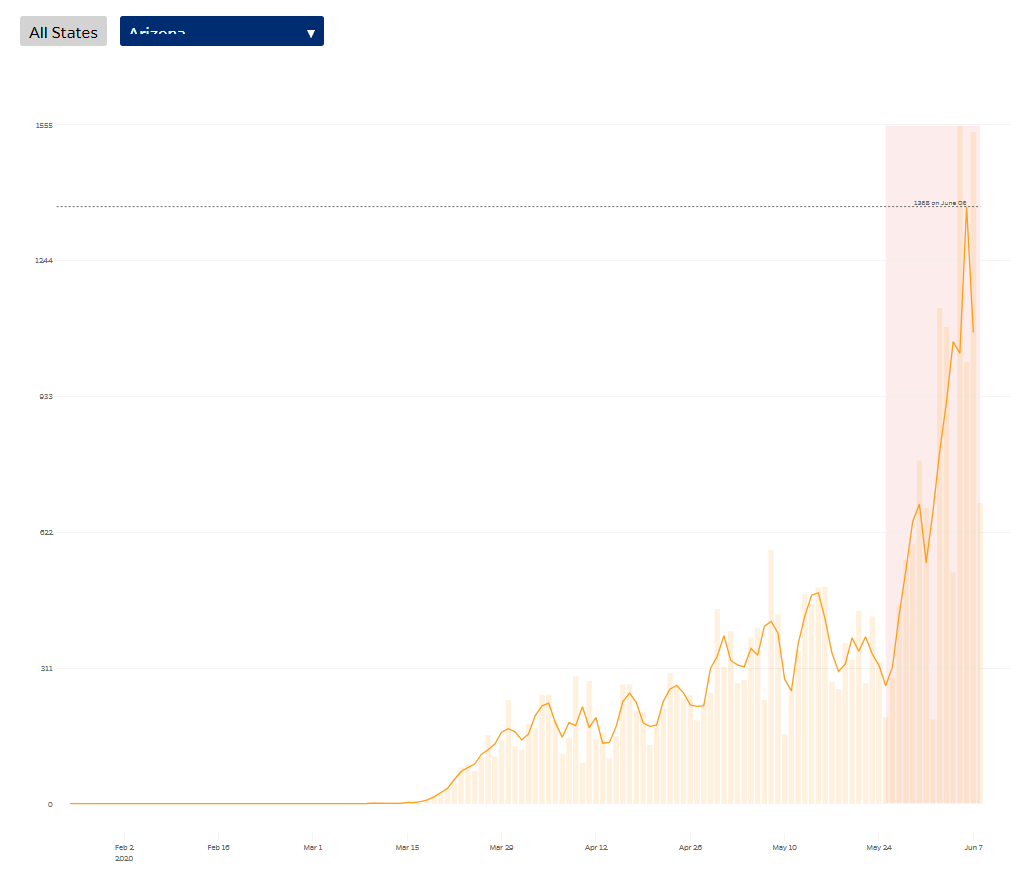

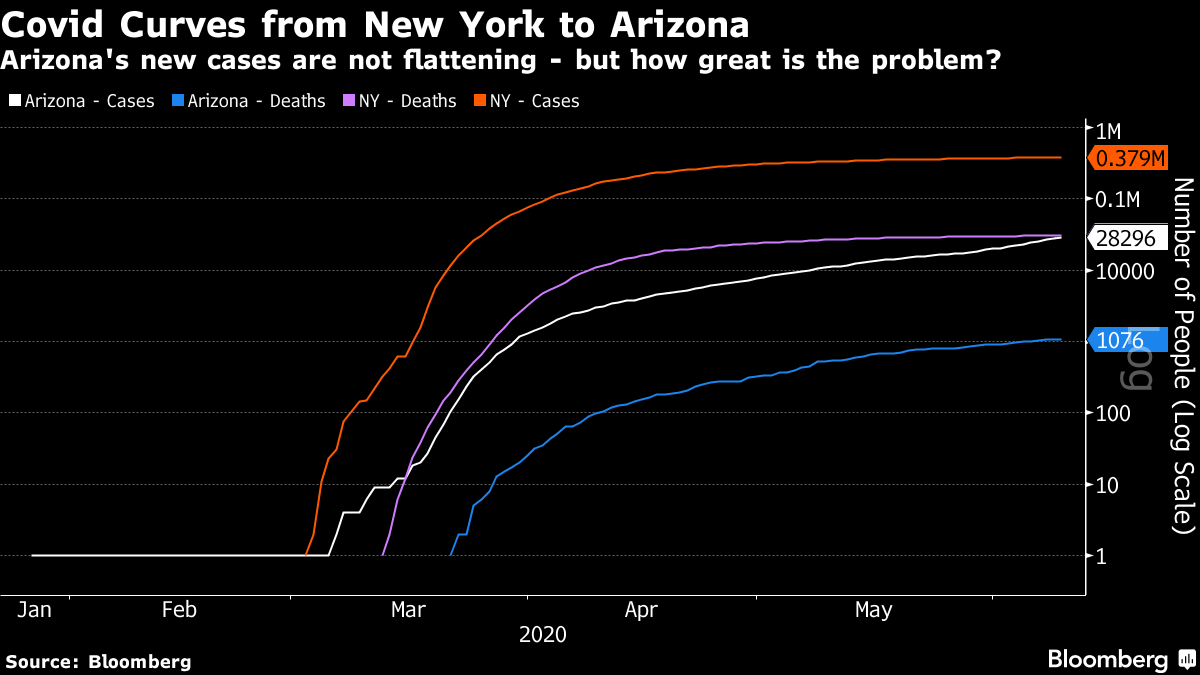

An Epidemic of Distrust "We must love one another or die," said W.H. Auden, in a poem that he wrote on New York's 52nd Street while waiting for news that the Second World War had been declared. It was the end of what he called a "low and dishonest decade." The poem bears re-reading, and if we alter his words slightly, we may be getting close to the fundamental problem of our age. We must trust one another or die. And for many reasons, widely covered, we no longer do. His lines came to mind as I tried to work out the risks of a serious second wave of Covid-19 in the U.S. This is clearly the greatest immediate risk out there, and the rally of the last few weeks (which took a pause Tuesday) has in large part been driven by the belief that the U.S. can avoid one. Now we confront two problems. The issue of reopening the economy has been politicized, with Republican governors generally re-opening their states more quickly than Democratic counterparts. And there is money running on it. If you are a bear or a Democrat, you want a Covid-19 second wave. (This assumes that you haven't a shred of human empathy, but these days, Republicans and bulls are probably prepared to believe that.) The opposite is true for Republicans and bulls. Meanwhile, health statistics are deeply complicated, while epidemiology is a far harder and more ambiguous subject than any of us realized. Furthermore, we are dealing with a virus whose existence has only been known for about six months. Even the foremost medical experts are making embarrassing U-turns in their interpretations and advice. Politicians and investors don't have expert knowledge of epidemiology, even though they need to know about it. And in the current heated environment, science is conducted in real time, with reports published swiftly before they have been peer-reviewed. Public debate, meanwhile, happens in large part on social media, where any number of non-experts can swiftly get involved. All of this is a preface for a case study that has left me almost as despairing as Auden. It concerns the fair state of Arizona. As luck would have it, Arizona is a "purple" state, with a Republican senator up for what could be a heated re-election campaign this year, while Democrats hope to win it in the presidential race. Its Republican governor reopened the state three weeks ago, earlier than many. Now, it is attracting attention as the site of a potential second wave. In particular this tweet thread from Banner Health, which runs the largest hospital system in the state, caught a lot of attention:  Monday also saw my Bloomberg Opinion colleague James Bianco, founder of Bianco Research, who has frequently counseled caution over Covid-19 in the last few months, tweet as follows: "What happens if/when a second wave occurs? Watch Arizona, cases are surging now and their hospitals are now at their limit. How will they flatten the curve? Another shutdown? Or, will they go the Sweden route and do nothing?" He accompanied it with this chart, which he credited to the New York Times:  I retweeted him, saying that this looked concerning. That provoked a reply, by Twitter and by e-mail, from a London-based investor, who said: Not complacent but people want to see the negative. Georgia data miles better so let's find another state! Minnesota cases should spike a lot today / tomorrow as day 15 since protests. Re Arizona worth checking data... cases up but testing up? Their dashboard clearly says hospitalisations down, deaths down and cases up as testing up. @BannerHealth, not sure what I miss? He also handily directed me to the Arizona Department of Health Services' Covid-19 website.  I looked up cases on the site, and indeed it showed a picture almost unrecognizable from the one painted by Banner Health and the New York Times graphic:  Cases have fallen off a cliff over the last five days. Then I looked up hospitalizations from the same dashboard. Given what Banner Health had been warning, the following chart is extraordinary:  How on earth could these numbers be reconciled, and was it even possible that everyone involved was acting in good faith? Actually, I do believe they were. The footnote to the Arizona DHS's chart says that cases are shown for the day on which a positive test was conducted, not on the day a positive result was discovered. There is generally a lag of 4-7 days. The sharp decline in the last few days is meaningless. Now we come to the hospitalization numbers. The Arizona DHS offers a number of other metrics. When I looked up the number of people in an intensive care unit with Covid-19, I got this graphic:  Other charts encouragingly show that the state has increased its provision of ICU beds and ventilators over the last few months, so it isn't at capacity — but it is of course possible that all the capacity is in sparsely populated corners of the state, far from overcrowded metropolitan hospitals. As I was by now getting very curious, I tried looking up Arizona's cases on the website kept by Johns Hopkins University, which has been taken as gospel by many over the last few months. Here it is:  The JHU site uses a five-day average to even out the trends, and finds an alarming peak with a promising decline in the last day to report — but plainly the data suggest that Arizona is, indeed, in the grip of a nascent second wave. Finally, I tried graphing Arizona on my faithful Bloomberg terminal, and compared it to New York, which for the time being is the clear example of what other states want to avoid. On a log scale, this is how cases and deaths have evolved in New York and Arizona:  The number of cases in Arizona is almost equal to the number of deaths in New York. Its curves are plainly upward-sloping still, whereas New York's have flattened. And Arizona has never seen growth as steep as New York witnessed back in March. I think I am back where I started. Arizona looks to me as though it is in a very parlous place, and all of us should be hoping that the state, with its sizable elderly population, is able to avert a significant outbreak. It doesn't prove to me that a second wave is inevitable, and that the economy can never reopen; but it strongly suggests that there is far more of a chance that Covid-19 does serious damage to life and property than market pricing currently assumes. I make these judgments in my capacity as a financial journalist, not an epidemiologist, following a debate with various other people, none of whom are epidemiologists. Much of the disagreement, in this case, was driven by subtle differences in statistics and the way they were presented. I don't think anyone involved is acting in bad faith, but the exercise of following the Arizona story through does drive home how easy it has been for different people to latch on to different versions of the truth. It would be better if we trusted a group of clearly identified people to decide how to fight this disease, and to inform us of progress. That isn't going to happen. That is partly because authority figures the world over have shown they don't deserve to be trusted. Shifts and corrections from epidemiologists have caused confusion, and quite possibly cost lives. It is also because in our current world, nobody trusts anyone anyway, and it becomes very easy to float misinformation, or to tar good information. The whole episode leaves me feeling almost as glum as Auden, sitting in his 52nd Street dive and digesting the news that war had broken out: All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

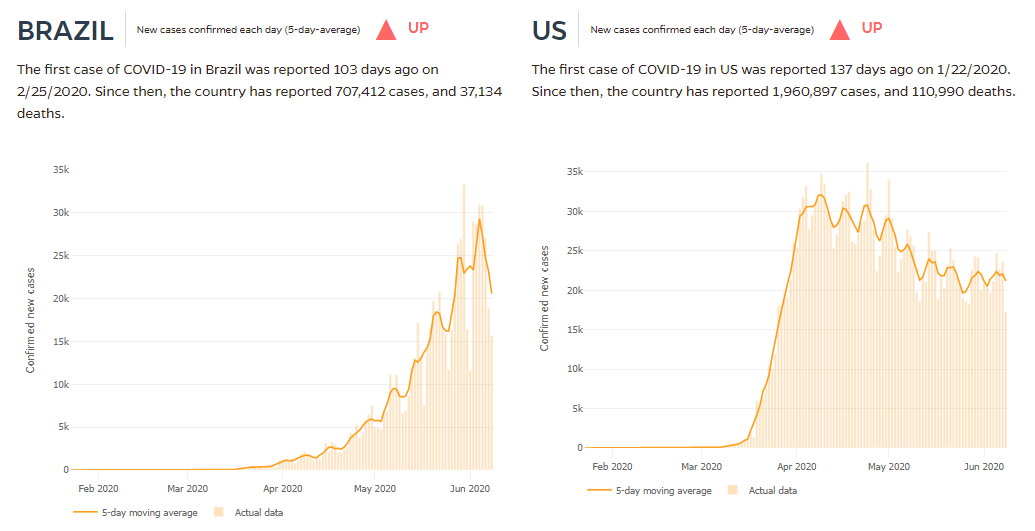

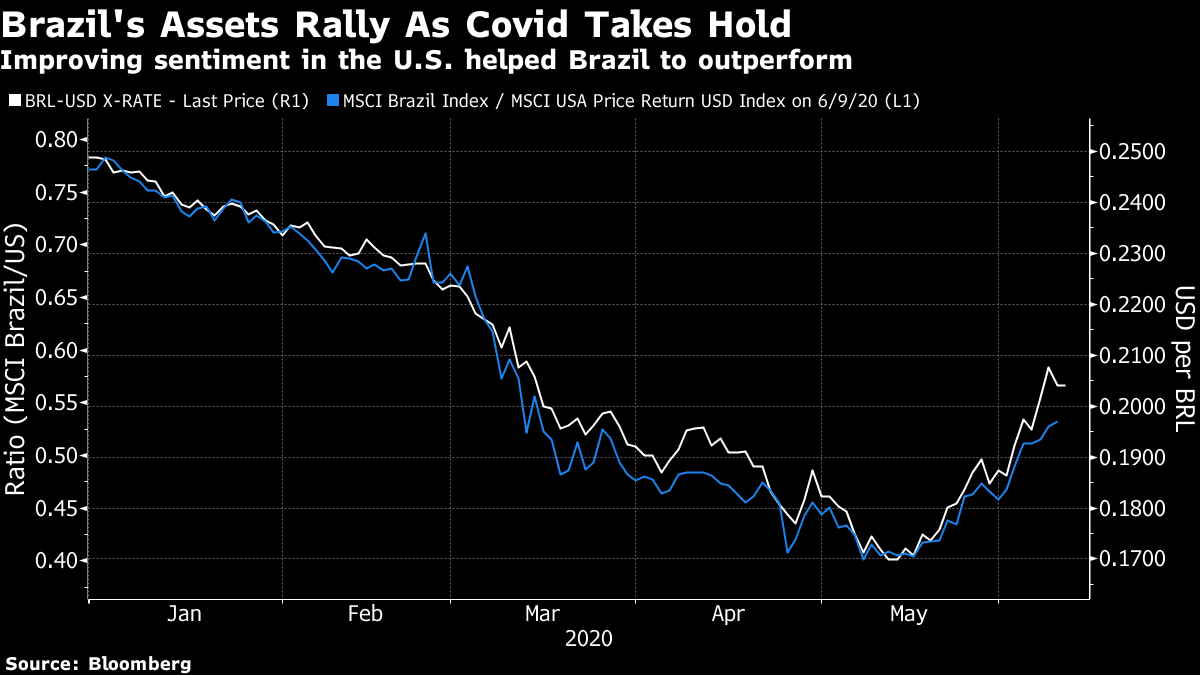

There's an Awful Lot of Covid in Brazil For a Covid-19 footnote, everyone in the U.S. appears to be doing a straightforward job in giving their people the information they need. The same isn't true of Brazil. Here are the JHU charts for cases in Brazil and the U.S. Note they are on the same scale, and that Brazil has a smaller population than the U.S.:  Brazil has a situation that is out of control. However, there is doubt about the figures, because the government has tried to stop publishing them. This is shameful. Brazil is now second only to the U.S. in the global league table of Covid-19 cases, and it looks painfully likely to overtake it. Its people have been utterly let down by its president, Jair Bolsonaro, in whom the markets invested much hope when he took over at the beginning of last year. How has this played out in the markets? Not as you might expect:  Brazilian assets have long been the most volatile of the major emerging markets, and the most prone to move in line with the ebb and flow of risk sentiment in the U.S. If Wall Street investors are feeling more confident, then Brazilian assets will generally rise, and more than American ones. This is true even if the source of concern is in the U.S., and even if the reason for feeling better in the U.S. is also a reason to feel much worse about Brazil. So the Brazilian real recovered against the dollar, and stocks there have outperformed U.S. indexes, even as the country has fallen into a serious outbreak. This isn't a new phenomenon. During the global financial crisis, driven primarily by the prospects of large banks in the U.S. and western Europe, the Brazilian currency moved at all times in line with the VIX index of U.S. equity volatility. It was seen as a pure adjunct of "risk," wherever that risk was situated.  It is hard to feel sorry for Bolsonaro at present. But we should feel sorry for the rest of the Brazilian population, and for those who are trying to build its economy when the most basic building blocks are driven by sentiment far away in Wall Street. Survival Tips I'm sorry to plug the work of an Englishman in New York again, but I really recommend reading Auden's September 1, 1939. I only looked it up to check a quote, and I've found myself reading and re-reading it. It's not cheerful but it does speak eloquently and directly to our current predicament. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment