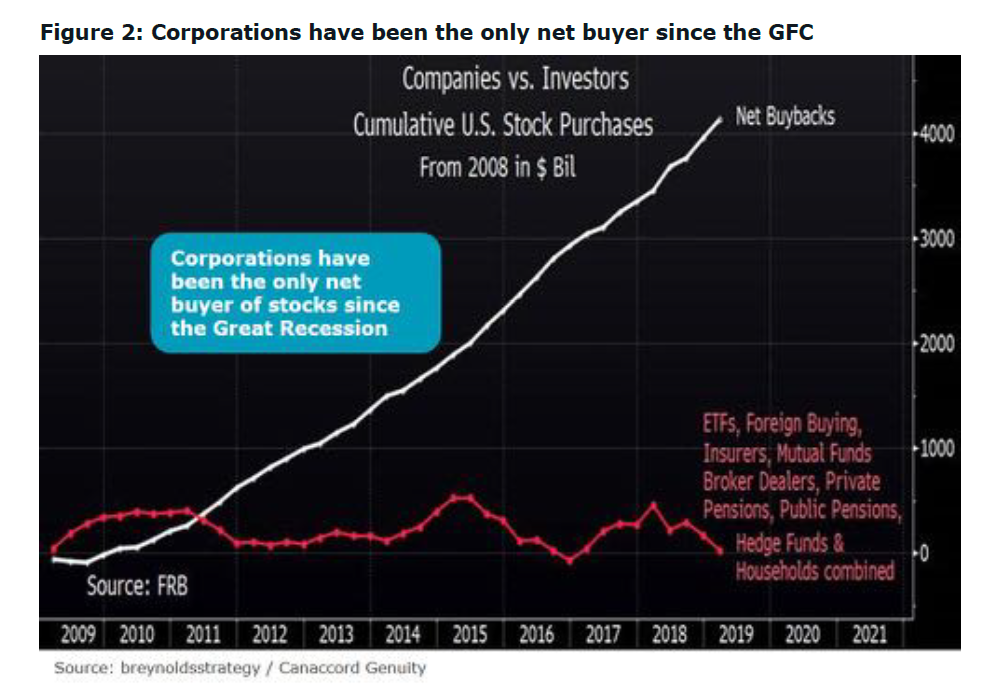

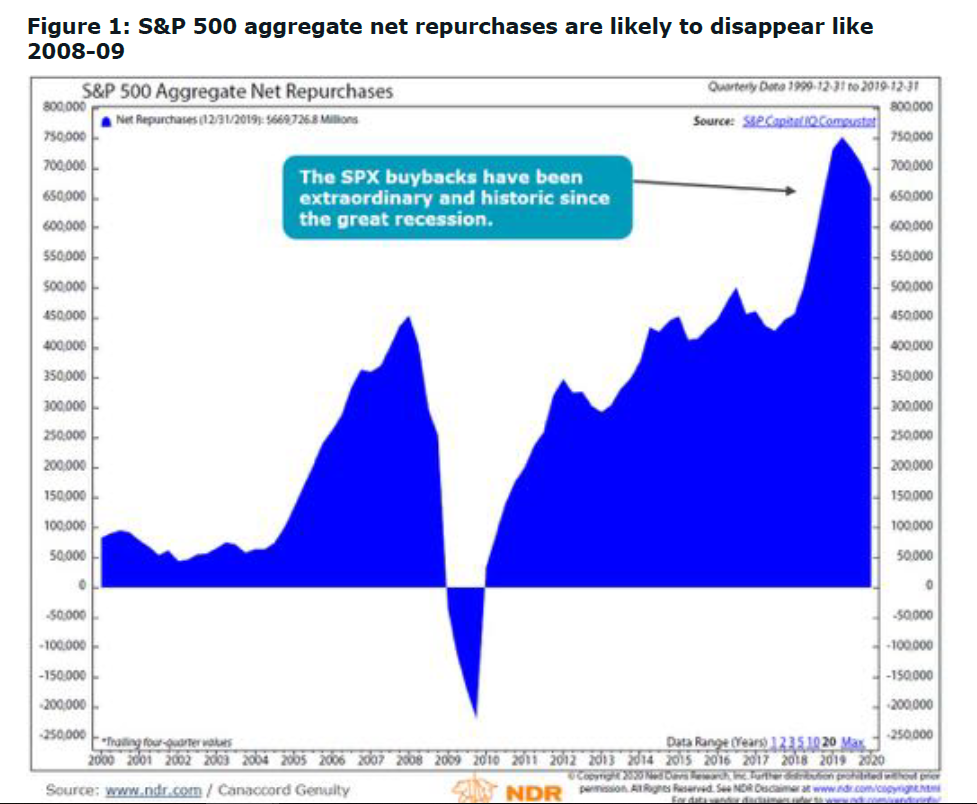

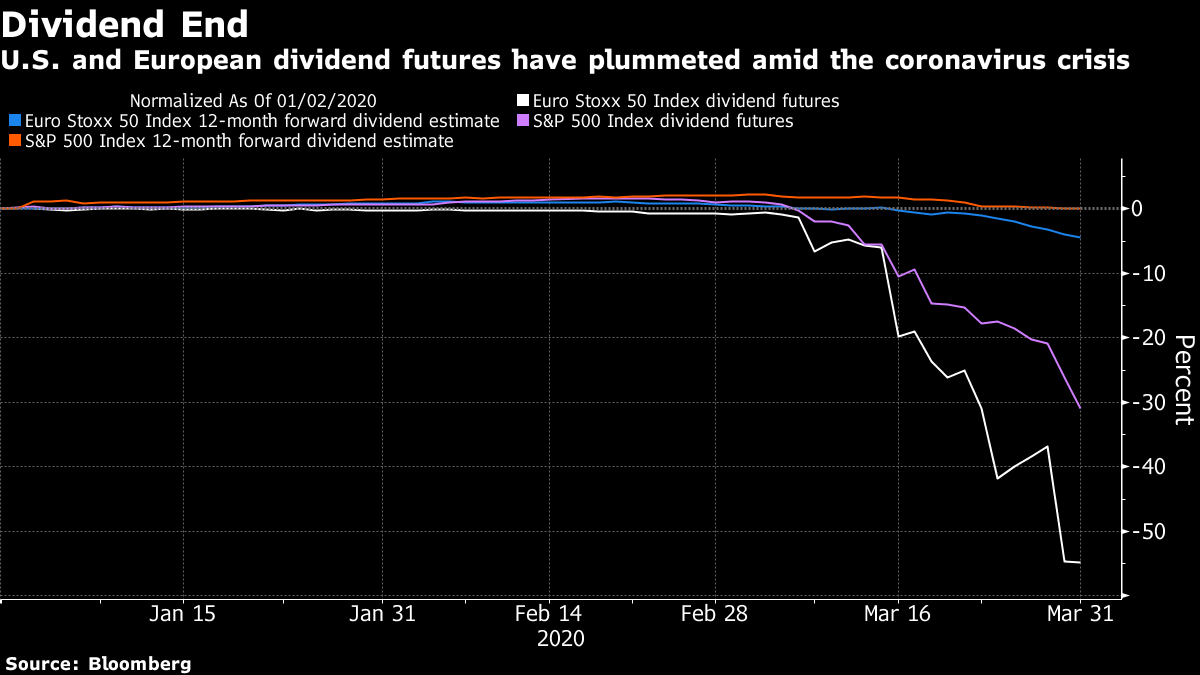

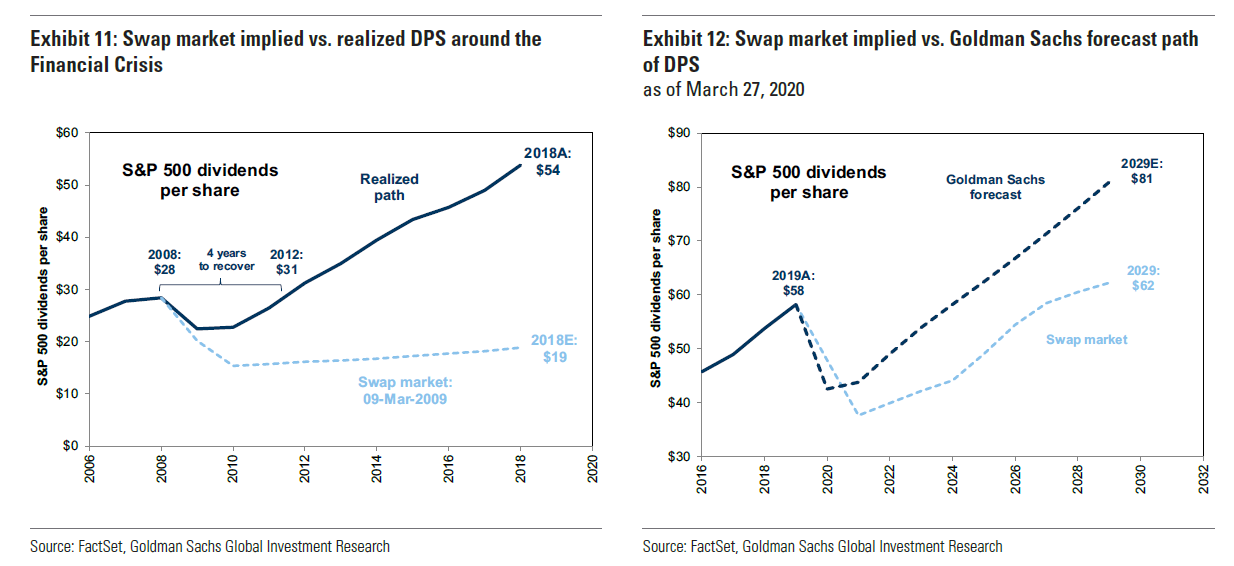

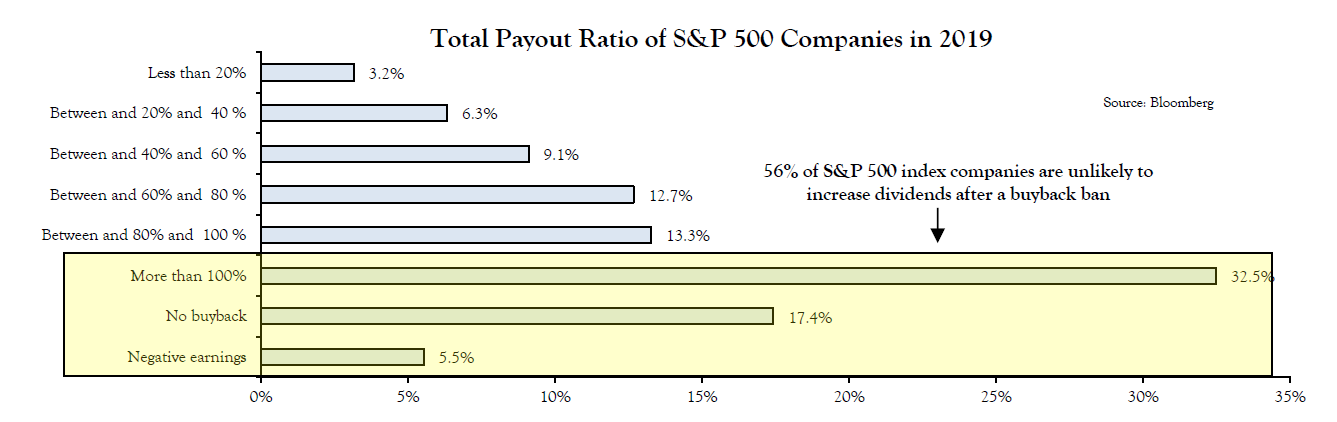

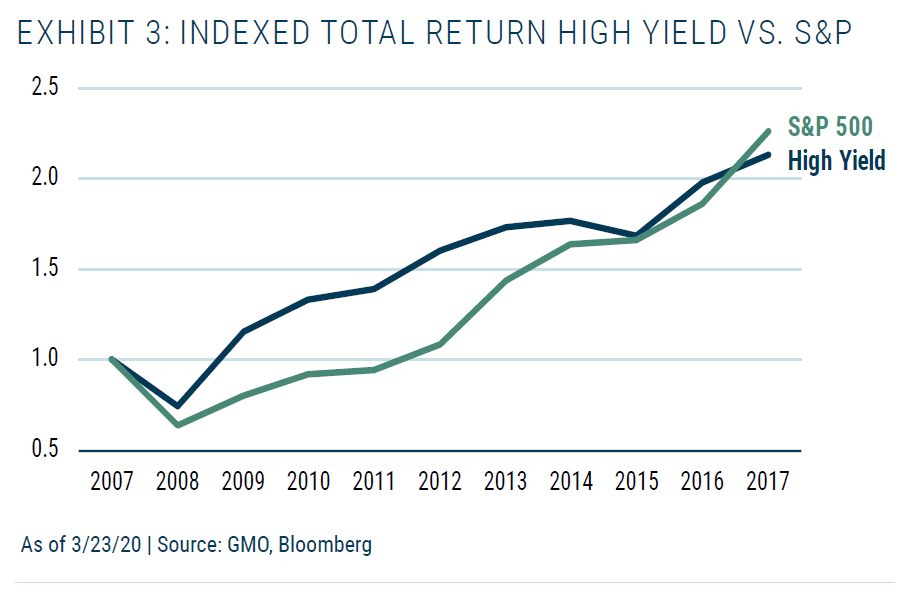

Follow the Money This was, in my experience, a joke-free April Fools' Day, which just about sums it up. With estimates for the spread of coronavirus in the U.S increasing, it was no surprise that stocks and bond yields took a fresh turn downward — although both remain within their remarkable ranges of the last month. With more people finding that the virus has touched someone close to them, the psychology is unsurprisingly negative. Nobody felt like buying stocks, or playing jokes. One of the clearest indicators that people are losing confidence is the focus on cash. That in turn suggests that an equity recovery could be a while coming — and that if there's a bargain opportunity out there, it's in credit. Specifically, investors are growing more worried about how much cash companies are going to be able to pay out. Corporate buybacks — taking excess cash and using it to shrink the share count, thus increasing earnings per share — have been by far the greatest source of demand for stocks since the crisis, as this chart from Canaccord Genuity Group Inc. makes clear:  After the last few weeks, it's fair to expect buybacks for the rest of this year to be close to zero. Airlines have already had a political and media pummeling for seeking government assistance after using large amounts of cash to pay shareholders. This shouldn't be dismissed as blind populism. It's true that buybacks are often a good way to direct cash toward more productive uses, when a company can see no great opportunities of its own — so they aren't necessarily as bad as they are often painted. But repurchases since the crisis have been on an epic scale. Cutting them out makes companies safer, and is a relatively straightforward, simple and fair way for shareholders to take some of the financial load of dealing with the virus:  Certainly, companies that bought back a lot of stock outperformed impressively over the post-crisis decade, showing why shareholders liked the practice. And their collapse in the last month demonstrates that the market is already pricing in a curtailment:  The other chief conduit to get cash to shareholders is, of course, the dividend. Current dividend yields are obviously utterly unsustainable. If investors could assume that companies will pay as much in dividends over the next 12 months as they did over the last 12, this would be the greatest opportunity to buy equities in decades. Of course, they can't:  There are derivatives markets to trade future dividend cash flows (which are far more advanced in Europe than in the U.S.). They show the market braced for European dividends to be halved, while U.S. payouts could fall 30%. Official forecasts haven't caught up. (Incidentally, the greater decline in Europe probably reflects the practice of maintaining a constant payout ratio, so that investors expect dividends to fall when profits fall; in the U.S., companies go to much greater lengths to avoid dividend cuts because they are taken as a negative signal.)  Is there is an opportunity here? The U.S. equity strategy team led by David Kostin at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. points out that the U.S. derivatives market braced for a far worse slump in dividends after the 2007-09 recession than in fact resulted. The Goldman team thinks this could happen again, and recommends loading up on reliable dividend-payers. Their overall forecast for the next year is very bearish, with a projected fall of 25% this year. Dividends have typically taken six quarters to return to their prior level after previous drawdowns, leading to the optimistic projection for the future:  As with so many other things, this projection seems reasonable given past financial history — but it requires some assumptions about the course of this pandemic that we can't yet make. It also requires some big assumptions about the actions of politicians. They are annoyed with companies for not having a lot of cash on hand, and therefore needing a bailout. Last year, almost a third of companies in the S&P 500 paid out more in dividends and buybacks than they made in profits, according to this chart from Vincent Deluard of INTL FCStone Inc. Such companies might decide it is impolitic to return to generous dividend payouts too quickly:  What about credit, then? Again, the most important assumptions are about the incentives for politicians and central banks. A decade ago, there was much money to be lost by failing to understand the readiness of the Federal Reserve to keep supporting the stock market. But another point seemed even more important to them. After the disastrous reaction to the Lehman Brothers failure, U.S. authorities assiduously protected corporate creditors. In the huge bailouts of big banks in the ensuing months, bondholders weren't required to take a haircut, while depositors were regarded as sacrosanct. Arguably that policy, combined with remarkably low interest rates, created the moral hazard that led companies to leverage up to the hilt, and investors to keep merrily lending to them. But with so much leverage out there, governments will be very reluctant to permit bankruptcies and defaults. And in any case, creditors are senior to shareholders. After the Lehman disaster, this chart from GMO LLC shows that high-yield bonds made back their losses after the crash far quicker than equities did. Indeed, measured from the prior peak, the S&P 500 wasn't ahead until 2016.  Hence the argument is that we should heed the way bailouts tend to work, look at the extent of the sell-off in credit, do a lot of homework, breathe very deeply, and buy credit. Rights and Wrongs Over the weekend, I published a long piece on the various possible moral responses to the coronavirus. Some other very interesting pieces on the morals of the pandemic are appearing. I can recommend David Brooks in the New York Times and this fascinating piece in the Financial Times by a retired neuro-surgeon. If you are more interested in podcasts, then Michael Sandel of Harvard University, the leading academic voice in favor of communitarian ethics and a staunch critic of markets, can be heard leading a multinational debate on this BBC podcast. The differences of opinion are fascinating. Meanwhile, my own prediction was that the next weeks and months may make all of us more prepared to follow the biblical "golden rule" to love thy neighbor as thyself, which has been translated into modern political theory by the philosopher John Rawls. That might still be true, but the email I received today from the manager of my New York apartment building makes clear that, as ever, plenty are happy to be immoral. All residents have been warned to look out for con artists: Generally, the following are some examples of scams that are being perpetrated: • The Coronavirus Stimulus Checks: As part of the federal stimulus package, eligible taxpayers will be receiving either a check or automatic deposit. If you are eligible, a direct deposit or check will be sent. Please don't listen to unsolicited offers to help. • Medicare or Healthcare Scams: People have called offering Coronavirus vaccines or other protective measures. They ask for social security numbers or credit card numbers. • Coronavirus Website Scams: You may receive an email directing you to a website offering protection against the Coronavirus. • Investment Advice/Opportunities: All have been impacted by the gyrations in the stock market. Scams about making money are always around. Now, the scammers are using the Coronavirus to play on heightened concerns. The virus is morally superior. Survival Tips: Self-Help Yesterday I suggested lists might be helpful, though I generally loathe them. Now, on to my least favorite literary genre: the self-help book. I generally dislike such books intensely. The experience of being sent a steady stream of review copies of books that promise to make their readers great investors, or negotiators, or salesmen, doesn't endear them to me. But I will make an exception for How to Think Like Leonardo Da Vinci by Michael Gelb, published in 1998. I summarized it many years ago and it continues to fascinate me. Gelb's idea was to examine Leonardo's life and his work habits, to try to understand how the great master enabled himself to make so many great breakthroughs in so many fields. This leads to a list of seven things we can all do to give our creativity the best chance to shine. They include curiosity (always carrying notebooks, using them, and returning to them); exercising (Leonardo was a fitness freak, apparently) and maintaining good posture; making our immediate surroundings as comfortable and beautiful as possible; and perhaps most importantly always looking for connections. Gelb also recommended learning to draw. Leonardo used drawing not just to plan his paintings, but to help him observe phenomena, and to understand how they worked. The exercise of trying to draw helps us to focus and is often surprisingly revealing. In unnatural conditions, it's worth a try. If we try to approach confinement as Leonardo would have, we won't necessarily produce a Mona Lisa, but we are likely to be a little more comfortable in our own skin, and a little more creative. That should help physical and mental health. And I intend taking a day for mental health tomorrow. Another newsletter will follow shortly. Good luck and stay safe. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

Post a Comment