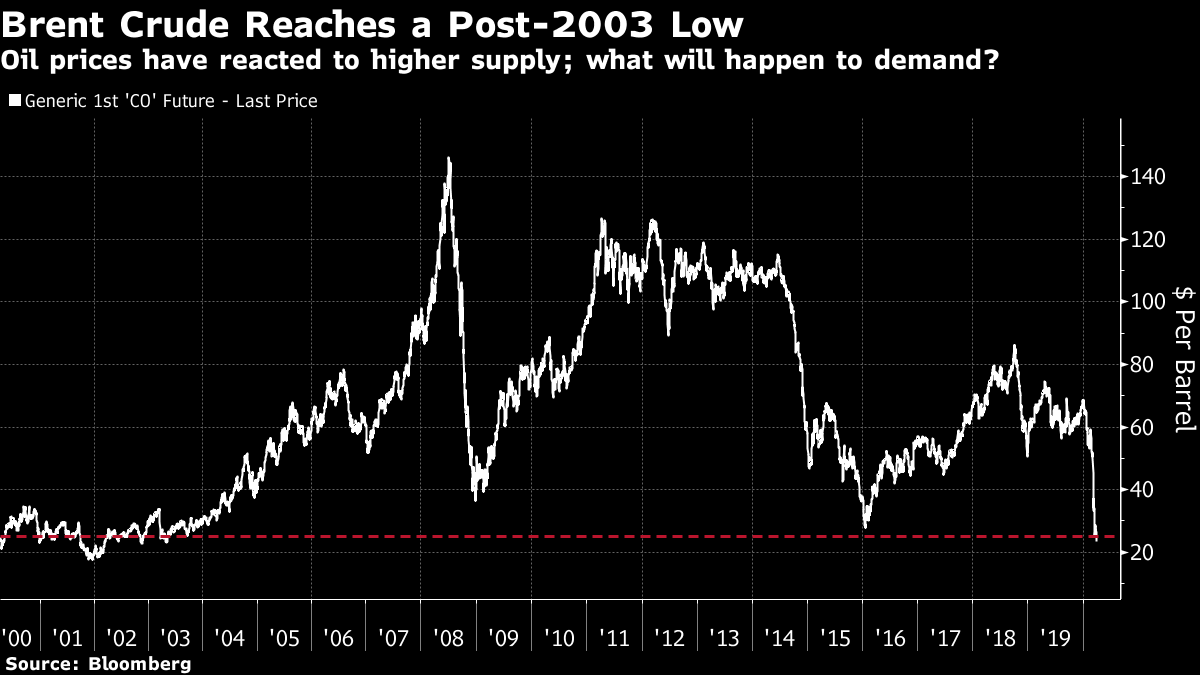

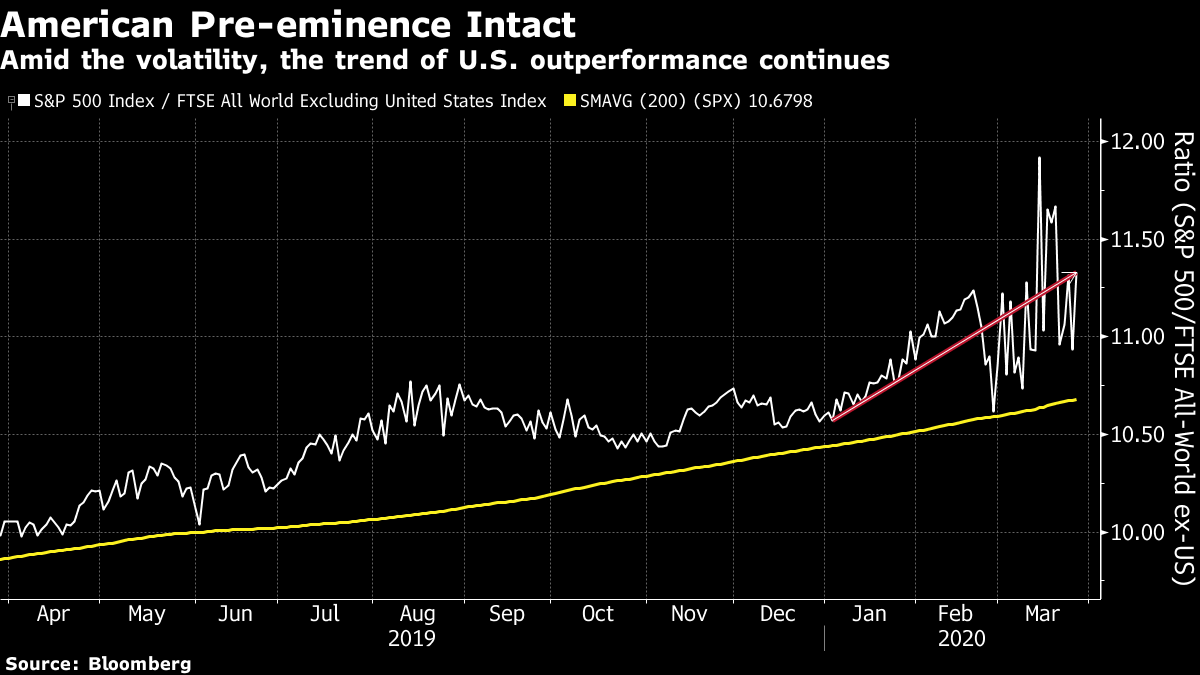

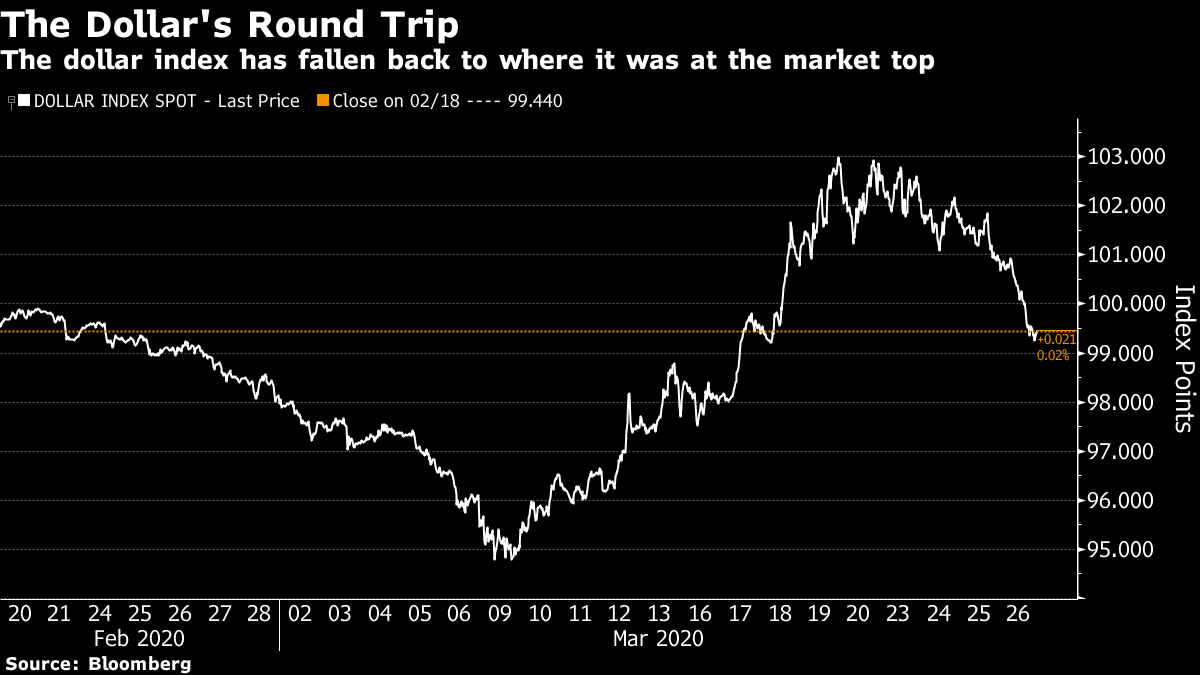

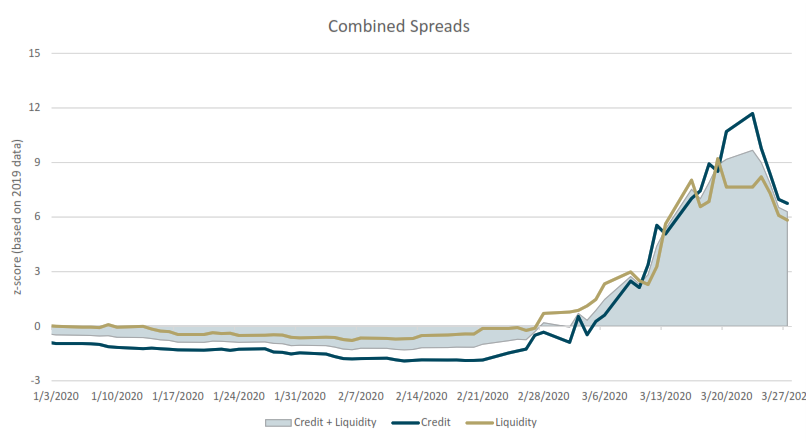

The Dollar vs The Contagion Another week is started, with another landmark. The price of Brent crude has fallen to a fresh 17-year low. The oil shock hasn't finished reverberating through international markets. The huge shock to supply from the breakdown of OPEC has now arguably been priced in. The critical question is the long-term future for demand as the world enters a coronavirus-induced recession:  Note that oil had been on a marked downward trend since autumn 2018. The OPEC breakdown was triggered by the stress of falling prices on oil producers. In the same way, if we look at the performance of U.S. stocks compared to bonds, or to gold, we similarly see a peak on Oct. 8, 2018. (By what I hope is total coincidence, that happens to be the day when I started working for Bloomberg.) As with the oil price, when we look at stocks compared to the most prominent shelter assets, we see a peak, followed by range-trading amid a general decline, and then a sharp fall once the virus shock hit:  In two vital measures of global markets' view of the economy, then, the virus shock has sharply accelerated trends that had been in place since 2018. Meanwhile, it has left another longer-term trend largely intact, albeit with much more volatility. This is how U.S. stocks have performed compared to FTSE's measure of the rest of the world. At no point has this trend dipped below its 200-day moving average, while the recent trend toward sharp outperformance remains intact:  So, where next? I suspect the critical variable to watch for the next few weeks will be the U.S. dollar. And the dollar's strength will in turn be determined by the variable that hangs over everything — the extent of the damage that the virus will ultimately wreak. These long-term trends may yet reverse, but that will depend on the virus more than on anything else. The dollar has moved dramatically several times as the crisis unfolded. This is the chart I showed at the end of last week:  The dollar entered the crisis strong, thanks to the early belief that the virus was primarily a Chinese issue. It fell as the Federal Reserve resorted to emergency rate cuts, making the currency a less attractive destination for carry traders. Then as the crisis took greater hold, there was a global demand for liquidity. The resultant dollar-buying drove the currency up sharply. At this point the dollar was arguably the clearest indicator of the depth of the crisis, and it implied serious pressure for emerging markets, where many companies have taken on dollar-denominated debt over the last decade of low interest rates. Adam Tooze of Columbia University even suggests that the coronavirus is the biggest emerging markets crisis ever. Then coordinated actions by central banks began to have an effect. The Fed offered dollars to a range of other central banks. As a result the pressure has diminished somewhat. It would be premature to say that it is over. This chart from John Velis, head of FX and macro strategy for Bank of New York Mellon Corp. in New York, handily combined four measures of credit (such as spreads of high-yield over investment-grade credit) and four measures of liquidity (such as the cost of getting dollar funding through the swaps market). It shows a distinct easing from the worst point, though still great tension:  It shouldn't be surprising that the dollar is acting like a measure of risk. The same thing happened during the credit crisis of 2008 and its aftermath, as shown by this chart from Steven Englander, chief foreign exchange strategist at Standard Chartered Plc:  The bazookas fired by central banks should have calmed things down, and that should mean continuing relative weakness for the dollar. One big reason, as far as the foreign exchange community is concerned, is that the differentials between U.S. rates and the rest of the world are fast narrowing. Higher rates will, all else equal, attract currency flows. But the differentials between U.S. and German bond yields, of both two years and 10 years, are as low as they have been since before the Fed started raising its benchmark rate in 2015:  Meanwhile, when it comes to monetary bazookas, the Fed hasn't gone anything like as far as the European Central Bank or the Bank of Japan in expanding its balance sheet. Now that it is effectively backstopped by the Treasury, it could go on quite a buying spree — which would, again, tend to weaken the dollar.  All else equal, therefore, we should brace for a weaker dollar, and for an end to the related long-term outperformance of U.S. stocks. But all else isn't equal. Instead, we have to calculate the impact of the virus, and whether its effects on the U.S. will be more or less severe than on other countries. History shows that the effects of an epidemic can endure for decades. Divergence on this issue could scarcely be wider. One argument is that the U.S. looks poorly positioned, and that its measures to blunt the impact will be less effective than in Europe, where governments are aiding workers much more directly. This might be the moment when the European model begins to look better than the U.S. once again. This is the view of George Saravelos, head of foreign exchange at Deutsche Bank AG: "The next phase will be about each country's ability to exit from the virus lockdowns as well as more traditional macro drivers of FX. On both fronts dollar fundamentals look poor. We worry we are now entering a new phase of policy, healthcare and economic "divergence" where the US looks worse than the rest of the world." It's also possible to posit that the U.S. will be less severely affected, simply because of geography. Unlike Europe, a large percentage of the American population lives in sparsely populated areas with minimal public transport. This is one of the possibilities raised by Englander, of Standard Chartered: "One scenario supportive of USD strength is if the outbreak proves impossible to contain in densely populated areas, but subsides in areas with low population density (of which the US has proportionately more than most countries). More broadly, any scenario in which the US mitigated the impact of the outbreak sooner than elsewhere would support USD strength." Then we come up against the fact that the fiscal response in the U.S. looks likely to be much bigger than in Europe, where creditworthiness is an issue, and agreeing on a common debt-funded expansion across a number of disparate countries is an even bigger one. This is the case put by Ben Randol, G-10 foreign exchange strategist for BofA Securities Inc.: Economic divergence has been a key theme over the last two years, with US fiscal stimulus propelling relative growth higher in 2018 and trade wars sustaining that advantage in 2019. For 2020, we think that the relative severity of COVID-19 shocks alongside the measures taken to counteract them will fundamentally determine the direction of exchange rates. The aggressiveness of the US fiscal policy response in comparison to that of many other countries (nearly 10% of GDP vs. 1% of GDP) and in particular that of the Euro Area, we think, is likely to sustain the US growth advantage again this year and provide a cyclical "pull" factor for the dollar. I am sorry to quote strategists at length, but the point is that sensible people can sketch out very different trajectories for the dollar — and hence for world markets and for the fate of many emerging economies — based on reasonable but totally different projections of the damage the virus will cause. Nobody should expect calmer market conditions, or any kind of a stable recovery, until the current funding crisis can be squelched, and until the final shape and extent of the virus damage is clearer. Ticker symbols matter. Years ago, psychology professors at Princeton University showed that a stock would perform better, all else equal, if its name was easy to pronounce, and if its ticker symbol could be spoken as a word. Big Lots Inc. enjoyed a big bounce when it changed its ticker from BLI to BIG; likewise Sun Microsystems when it switched from SUNW to JAVA. Sponsors of exchange-traded funds are well aware of this, which explains tickers like MOO (agricultural products) or EMTY (which bets against bricks-and-mortar retailers). The coronavirus has given us a classic example. One of the stars of the last few weeks has been Zoom videoconferencing technology. I have watched people putting on plays using it; I gave a talk on Zoom last week; and my kids are doing all their classes using Zoom. If ever there was a product that has perversely benefited from the virus, it is Zoom. Naturally enough, many investors went out and bought Zoom Technologies Inc., whose ticker symbol is ZOOM. The price of this small and closely traded stock was at one point up eightfold within a month. The one problem is that Zoom videoconferencing is made by a different company called Zoom Video Communications Inc., which went public last year with the ticker symbol ZM. This is how the two stocks have performed since Zoom Video Communications' IPO:  In part this shows the behavioral importance of a ticker symbol. It also shows that a disquieting number of people will invest in a company without even being sure what it is. Many will have done so with other people's money. Disappointed clients who find they've invested in ZOOM should ask: "Who's zooming who?" Survival Tips I will try to make this a daily feature for those dealing with self-isolation. To start with, by far the best movie my family has streamed on Netflix has been Searching for Sugar Man, which won the Oscar for best documentary in 2012. It tells the incredible story of an American singer-songwriter who released two albums in the early 1970s, got dumped by his record label, and returned to his job as a construction worker in Detroit, all the time ignorant of the fact that he had developed a huge following in South Africa, where people thought he was "bigger than Elvis Presley." It's wonderful and moving, it entertains all the family (a rare feat), and it introduces some extraordinary music. Try listening to "I wonder", and then wonder how this man did not get to be a household name. All survival tips gratefully accepted. Have a good week. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. |

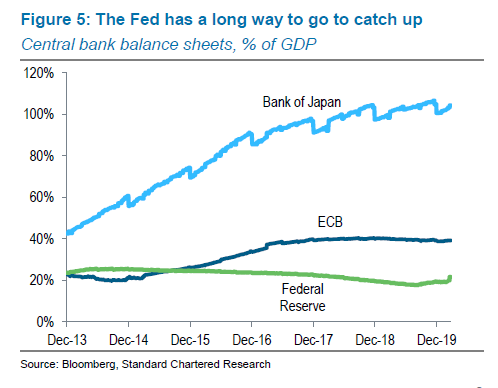

Post a Comment